Introduction

The history of state tyranny has many examples of terrible repression, brutal conquest and atrocity. In the view of French political scientist Alain Besanson, however, the 20th century represented a distinct “century of horrors.” Among the worst horrors was the Nazi regime’s effort to exterminate European Jewry in the Holocaust. Six million Jews — two-thirds of European Jewry — were killed in a systematic campaign of murder. More generally, new forms of state tyranny in Fascism and Communism achieved such a level of control, oppression and violence that a new term was coined to describe them as political systems: totalitarianism.

To understand the concept of state tyranny, it is necessary to describe its effects. This makes for hard reading. The description below is one example.

When American soldiers entered Germany and liberated the network of concentration camps at the end of World War II, what they encountered brought awful clarity to the struggle against Nazi tyranny. Sergeant Ragene Farris, a medic with the 329th Medical Battalion of the 104th Infantry Division, arrived at the Nordhausen subcamp in the Mittlebau-Dora complex. He wrote:

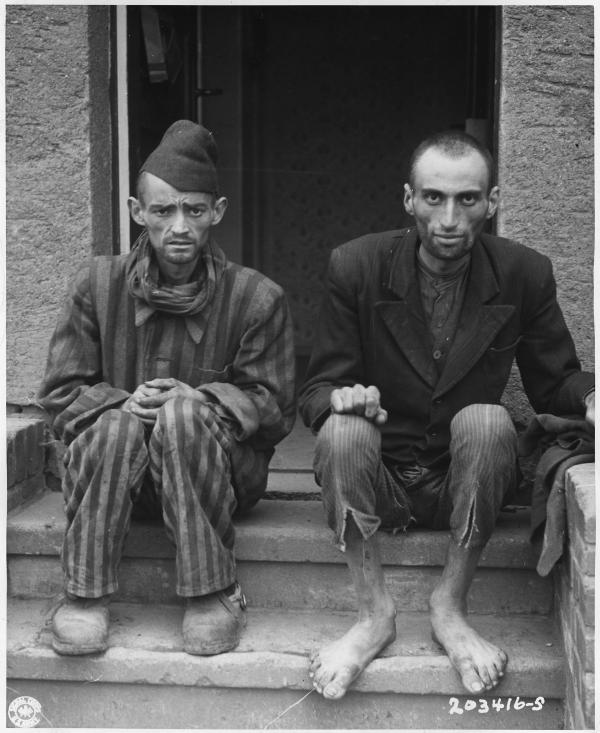

Two prisoners at the Mittel Brau subsection of the Nordhausen death camp, where prisoners were used for forced labor producing V-1 rockets. US battalions found 3,000 prisoners worked and starved to death. Medics saved 700 surviving prisoners inside the barracks. Public Domain. National Records and Archives Division.

[T]he buildings were used for housing political prisoners of all nationalities, forced to work as slave labor in the underground factories located near the camp. With stretchers in our hands, we ran into the nearest building. . . . Under the stairway, we found a pile of 75 corpses, a vision of horror I'll never be able to forget. On the second floor, there were 25 other men — all dead. Then we found some others lying on wooden bunks. Strangely they didn't move. They were fighting against death but they were still alive. . . . Once we entered in the cellar [t]he air was filled with the odor of death, foul human waste and almost unbearable. I saw inmates in their bunks, unable to move, with the bodies of their dead comrades lying on them. . . .

We saw several bodies of prisoners who were shot by machine guns while they tried to escape the fury of their SS guards. . . . One [prisoner] told me that many of the 3,000 dead in the camp had been worked, beaten, and forced at top speed until they could work no longer, after which they were starved off or killed outright. We worked hours after hours, trying to save as many human lives as we could. We transferred this day 300 inmates to the temporary hospital, as well as 400 others who were able to walk.

One may find many more such accounts (see Resources).

The extent of the horrors carried out by the Axis Powers of Nazi Germany, Italy and Japan prior to and during World War II fundamentally changed how the world approached human rights.

Prior to World War II, the League of Nations had sought, but failed, to hold nations accountable to some basic rules of international behavior, such as non-aggression. But human rights were a matter mostly to be determined by each state. The extent of the horrors carried out by the Axis Powers of Nazi Germany, Italy and Japan prior to and during World War II fundamentally changed how the world approached human rights.

As described below, there emerged a new world consensus to establish universal standards of conduct to which nation states and sovereign territories (including colonial powers) and sovereign territories must follow. Through United Nations adoption of the UN Charter, universal standards of international behavior would be established both to prevent state aggression and to end state tyranny.

Universal Standards for Human Rights

On December 10 1948, the General Assembly of the United Nations, then with 56 members, adopted the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The first code was to prevent further acts of genocide; the second was to foster universal protection of basic human rights. Both set the standards that all member states of the UN pledged to respect.

Human rights, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights asserted, are the “highest aspiration of the common people.” Their recognition would establish for humankind “the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world.”

The most important principle of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), and its first article, is that “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” The UDHR's next twenty-nine articles enumerate a broad array of rights affirming both freedom and equality. They include the rights "to life, liberty and security of person"; the right of self-governance; the rights of free expression, association, assembly and religion; and the rights to work, an adequate standard of living, health care, education and leisure. Also protected are the basic rights to emigrate and find asylum, which is further set out in the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. It pledges nations to the principle of “non-refoulement,” meaning that a refugee must not be returned to a country where they face serious threats to their life or freedom. (This has been until now the foundational basis for US immigration law.)

Most of the UDHR's civil and political rights had been previously put forward as essential to democracy through such documents as the English Bill of Rights of 1689, the US Declaration of Independence and Constitution, and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man, among others (see also History).

Most of the UDHR's civil and political rights had been previously put forward as essential to democracy through such documents as the English Bill of Rights of 1689, the US Declaration of Independence and Constitution, and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man, among others.

Also, following the First World War, many social and economic rights had been recognized in conventions of the International Labour Organization, a separate but associated organization to the League of Nations (see also Freedom of Association). But putting political rights and social and economic rights together as a framework for universal rights for all people and all countries was new. All of these would now be protected by a framework of international law and institutions.

What are essential principles of human rights? Are human rights imposed as a "Western" concept, or are they universal as asserted by the UDHR? Do civil and political freedoms have priority over social, economic and cultural rights? Some answers to these questions lie in how the UDHR and subsequent conventions were adopted. This is discussed below.

Different Models

One large difficulty in drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was that it involved the participation of representatives of anti-democratic regimes that had little respect for human dignity or inalienable rights. Within the United Nations and its nine-member Human Rights Commission, the main such regime was the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).

One large difficulty in drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was that it involved the participation of representatives of anti-democratic regimes that had little respect for human dignity or inalienable rights.

The USSR began World War II as a partner of Nazi Germany in the conquest of Europe. But after Adolf Hitler broke their non-aggression pact and invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, the USSR joined the Allied Powers (the United States, United Kingdom and others). After the Allied victory in World War II, however, the USSR returned to being an antagonist to Western democracies. Its leader, Joseph Stalin, used the period after World War II to consolidate control over Eastern European countries that the Soviet Red Army had occupied and the USSR also acted aggressively to extend its reach elsewhere in Europe, Latin America, the Middle East, Africa and Asia.

The USSR presented an alternative model of governance, namely a police state with total control over the economy governed under an ideology called Marxism-Leninism. The Soviet delegation to the UN Human Rights Commission asserted the ideological primacy of "higher” economic and social rights against civil and political rights guaranteed by democracies.

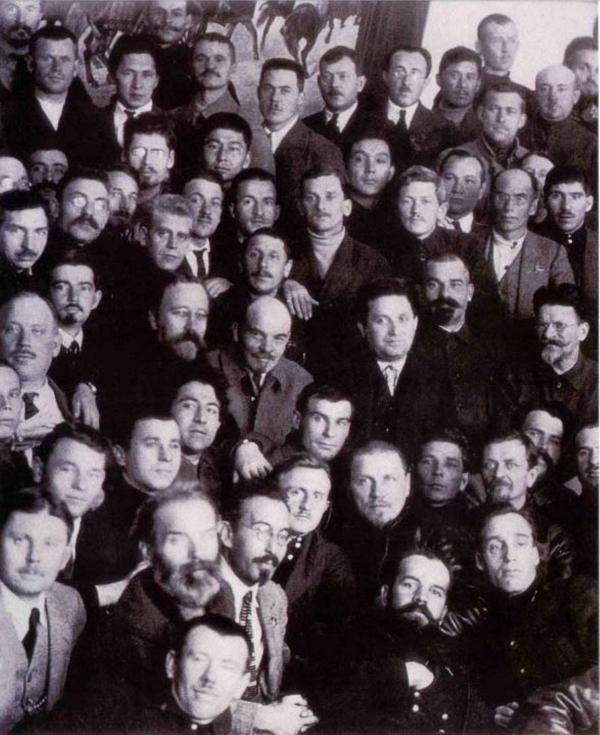

At UN meetings, Eleanor Roosevelt frequently faced off against the representative of the USSR, Andrei Vyshinsky. He is shown here to the right of the early Soviet leader Lenin (in the middle, with goatee) at a 1922 Communist Party Central Committee meeting. Many in the photo would be executed after being tried by Vyshinsky as Stalin’s Prosecutor in the Great Purge Trials. Public Domain.

Eleanor Roosevelt, the former First Lady and head of the US delegation, served as chairman of the Human Rights Commission. She spent considerable effort contending with the head of the Soviet delegation, Andrei Vyshinsky. Vyshinsky was himself a notorious human rights violator as Stalin's prosecutor general during the Great Purge trials of the 1930s. (The Great Purge resulted in an estimated one million executions and four to six million people sent to forced labor camps.)

Eleanor Roosevelt — and most other countries’ representatives — insisted on the maintenance of individual and political rights within any charter. They also agreed to including social and economic rights. After all, these had been essential to Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s assertion of Four Freedoms and proposal for an Economic Bill of Rights as well as to post-war social democratic governments in Western Europe (see also History in Economic Freedom). But representatives of free countries rejected that this second category of rights required an all-powerful state and the destruction of civic and political rights to implement them.

Differentiating Rights

Commission members and the General Assembly agreed to move forward by adopting a single Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) that included basic standards to both sets of rights.

Commission members and the General Assembly agreed to move forward by adopting a single Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) that included basic standards to both sets of rights.

A more detailed “International Bill of Rights” with specific obligations for states to adhere would then be made in two parts: the UN Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the UN Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (both adopted in 1966). The UN would adopt additional human rights instruments such as the UN Convention Against Torture (for a link to UN human rights conventions, see Resources).

The separation of the International Bill of Rights into two parts led to a differentiation of human rights. Some defined them as individual (civic and political rights) and collective (economic, social and cultural rights). Others categorized them as first generation (individual rights), second generation (social or collective rights) and third generation (global rights). Political philosophers distinguished between negative rights (freedoms that governments may not take away, such as due process and freedom of expression) and positive rights (those that governments must provide, as in the rights to education or, as an example of global rights, a sustainable planet).

In practice, the UN system established a hierarchy through the oversight of its conventions. While all categories of rights are recognized, the most significant for the UN Human Rights Commission — it was later reconstituted as the UN Human Rights Council — was the distinction between derogable and non-derogable rights.

Non-derogable rights refer to what governments shall not do under any circumstances. . . . [G]overnments may not restrict all rights generally, or destroy ethnic or national groups or their cultural heritage, or commit aggression or war crimes against another country, or indiscriminately kill, persecute, enslave, torture or exile one's own citizens.

Derogable rights are those that governments may infringe in states of emergency such as during internal violent conflicts or natural disasters. In such instances, freedoms of expression, assembly, association and due process rights may be infringed, but only for limited time periods.

Non-derogable rights refer to what governments shall not do under any circumstances. . . . [G]overnments may not restrict all rights generally, or destroy ethnic or national groups or their cultural heritage, or commit aggression or war crimes against another country, or indiscriminately kill, persecute, enslave, torture or exile one's own citizens.

Differentiating Rights (Cont.)

In this framework, civil and political rights had primary consideration within the UN Human Rights Commission on the grounds of non-derogable rights. Countries that murdered and jailed opponents and violated basic rights without distinction — that is, those that practiced state tyranny, as described above — had greater scrutiny.

Clear precedents established that governments cannot willfully declare martial law or states of emergency to infringe human rights.

As well, clear precedents established that governments cannot willfully declare martial law or states of emergency to infringe human rights. In the early 1980s, for example, the UN Human Rights Commission rejected the Polish government’s justification for imposing martial law. It had imposed martial law to violently repress the Solidarity trade union movement. The Commission concluded that the Solidarity movement posed no threat to public order and that Polish workers were exercising basic rights.

Still, economic, social, and cultural rights have been protected through the UN framework, especially social and cultural rights of ethnic groups and indigenous nations (see also Majority Rule, Minority Rights). As well, the World Conference on Human Rights in 1993 established economic development as a basic global right. The UN adopted an overall framework for countries to strive for development goals.

Democracies generally adopted constitutions, government practices and social and economic policies that adhered more or less to both sets of rights put forward in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. This includes treatment of ethnic and cultural minorities (see below and History).

Non-democratic governments have violated both civil and political rights and economic, social and cultural rights. For example, the assertion of “higher” economic and social rights by the Soviet Union and other communist governments masked the practice of mass imprisonment, forced labor and conditions of generalized poverty and deprivation. In addition, the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China carried out systematic policies to repress or destroy national, ethnic, cultural and religious minorities.

Human Rights Advancement

Just as the United Nations Charter did not end state aggression, neither did the Genocide Convention end ethnic cleansing or genocide. Nor, as indicated above, did the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) end state tyranny. Nevertheless, these documents established a framework for the advancement of fundamental principles in the international behavior of states.

Just as the United Nations Charter did not end state aggression, neither did the Genocide Convention end ethnic cleansing or genocide. Nor, as indicated above, did the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) end state tyranny. Nevertheless, these documents established a framework for the advancement of fundamental principles in the international behavior of states.

Thus, the UN Charter and the UN system of collective security has helped to prevent world-wide conflict and repelled numerous cases of state aggression (as in the Korean peninsula in the 1950s and the Persian Gulf in 1991). The UN Charter and the Genocide Convention led to international interventions to stop ethnic cleansing and genocide in some, if not all, instances. (Bosnia and Hercegovina and Kosova are two examples in the 1990s.) Also in the 1990s, a special international court system was established to investigate and prosecute crimes against humanity and genocide in former Yugoslavia, Rwanda and some other states.

The UN Charter and the UDHR were also significant in advancing decolonization in Africa and Asia and establishing principles of self-governance and human rights on an international scale. For example, the UDHR is the basis for the European Convention on Human Rights, the Charter of the Organization of American States and the African Union Charter on Human Rights and People’s Rights. The Council of Europe, the OAS and the African Union all set up continent-wide systems for accountability for human rights.

The advancement of human rights included the United States. Most significantly, as the UDHR was being signed, A. Philip Randolph led national protests to end segregation in the armed forces. He and other civil rights leaders appealed to the UDHR and its principles of equality and anti-discrimination to build domestic pressure for President Truman to sign Executive Order 9981 on the Desegregation of the Armed Forces. Similar appeals were made throughout the 1950s and 1960s during the Civil Rights Movement for adoption of civil rights legislation to finally make the United States a full democracy.

Dissidents in Soviet bloc countries organized Helsinki Committees to monitor compliance of communist governments on issues of human rights

Through international and continental systems of accountability, the UDHR was also a foundation for much of the “third wave” of democracy that took place from the 1970s to the 2000s, starting with the overthrow of fascist governments in Greece, Portugal and Spain and then continuing with the toppling of authoritarian regimes in Africa, Asia, Latin America and Eastern Europe.

The Helsinki Final Act, for example, pledged NATO and Warsaw Pact countries to adhere to the UDHR as part of an overall security agreement to reduce the possibility for military conflict. Dissidents in Soviet bloc countries organized Helsinki Committees to monitor compliance of communist governments on issues of human rights for presentation in follow-up meetings. In 1980, Polish workers cited provisions guaranteeing freedom of association in the UDHR and in International Labour Organization Conventions to demand the right for independent trade unions as well as other basic rights. Despite later repression under a martial law regime, the Polish Solidarity movement inspired a decade of human and worker rights activism in Central and Eastern Europe that brought about the collapse of Soviet-imposed regimes and the establishment of democracy (see Poland Country Study).

Human Rights Resisters

Of course, many UN member states have continued to violate human rights on a massive scale. During the Cold War, Soviet communism posed the single greatest challenge to universal human rights standards, but other justifications for violating human rights based on racism (as in South Africa), theocracy (as in Saudi Arabia and Iran), or national security (as in Bolivia, Chile and Guatemala) were prevalent.

The continued violation of human rights did not negate their universality. Indeed, countries resisting human rights still formally recognized the legitimacy of universal human rights principles by signing the international conventions of the United Nations. Their propaganda would claim that their countries adhered to human rights instruments — against all evidence — not that they were invalid.

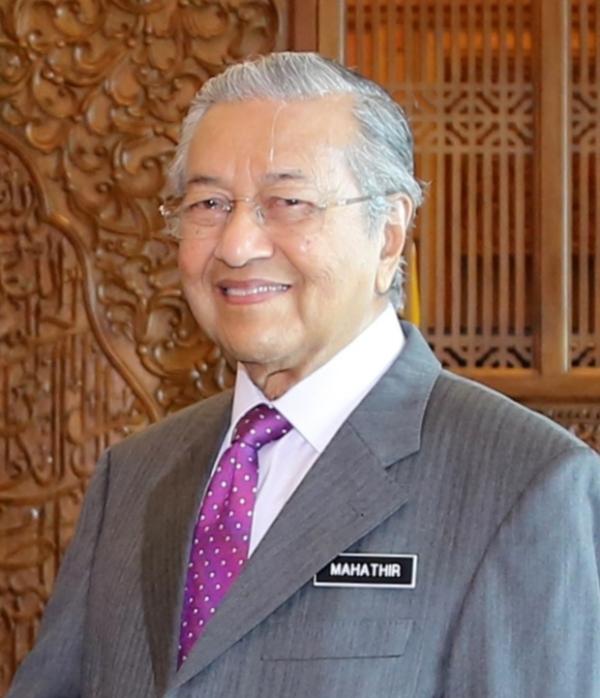

Mahathir Mohamad was one of several Asian authoritarian leaders who argued against democracy and human rights as “Western” concepts. He changed views and in 2018 came out of retirement to lead a democratic coalition in elections. Shown here at an event as prime minister in 2018 at the US Embassy. Public Domain.

One stubborn argument against the universality of human rights was made by authoritarian leaders in Asia such as Lee Kuan Yew and Mahathir Mohamad, the former prime ministers of Singapore and Malaysia (see Country Studies). They defended their regimes’ authoritarian systems arguing that democracy and human rights are Western concepts incompatible with Asian principles based on respect for authority and social uniformity. They argued that Asian countries such as theirs developed well economically and achieved political stability through more authoritarian practices. The leaders of the People’s Republic of China also argued against democracy as a foreign concept. In the last decade, President Xi Jinping ordered a crackdown on teaching Western political thought at Chinese universities.

Yet, the argument does not hold up. While Singapore, Malaysia and the People’s Republic of China may have economic achievements, Asian democracies that respect civil and political rights are more economically well-off and politically stable. Such examples as Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, as well as Indonesia and Philippines, make clear democracy is not “Western” or foreign. These countries demonstrate that the arguments justifying Asian authoritarianism are just a cover for repression and avoiding international obligations under UN conventions. Notably, Mahathir Mohamad himself had a late-life change of course due to the high-level corruption that took over his party. As described in the Malaysia Country Study, he joined a democratic coalition and then led it to a majority victory in Malaysia’s 2018 elections.

Assessing Essential Principles

For the past 75 years, when citizens in Asian, African, North and South American, and European societies have been free to choose their futures, they mostly have chosen democracy and the essential principles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights over authoritarianism and repression.

For the past 75 years, when citizens in Asian, African, North and South American, and European societies have been free to choose their futures, they mostly have chosen democracy and the essential principles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights over authoritarianism and repression.

At the same time, citizens are too often denied this opportunity to choose. Since 2006, Freedom House has recorded 18 straight years of declines in human rights indicators in its annual Freedom in the World survey. “Not free” countries such as the People’s Republic of China (see Country Study) and the Russian Federation have become more repressive and adopted policies similar to their totalitarian pasts. Some countries (such as Venezuela and Turkey) moved from the “partly free” to the “not free” category.

Others moved from the “free” to “partly free” category (such as Hungary, India, and in this section Indonesia). The “not free” and “partly free” Country Studies in Democracy Web describe the varied ways in which governments deny their citizens human rights and deny citizens the chance for free and fair elections.

Freedom House has even recorded a steady decline among a number of “free countries” in their adherence to human rights and democratic principles. These include France, Israel, Poland and the United States among Democracy Web Country Studies. In the United States, for example, various states have infringed voting rights and rights of representation and participation in government (see Free Elections).

The balance sheet for human rights is incomplete. There remain, as the UDHR states, "barbarous acts that outrage the conscience of humankind." Yet, since the UDHR was adopted to address such acts, there have been significant advances in freedom from state tyranny and human rights.

Still, as described above, the broad trend since the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 is more positive. That trend speaks to the overall impact of adopting a clear charter for human rights, monitoring their compliance, and adopting policies to promote the democratic principles and rights of the UDHR. As of 2023, the number of “free” countries where human rights are generally respected was 84 out of 195 countries, an increase of 40 since the survey was first done in 1973, fifty years ago. An additional 36 countries counted as electoral democracies having “partly free” systems where human rights are respected — or more precisely where citizens assert their rights — to some degree.

The balance sheet for human rights is incomplete. There remain, as the UDHR states, "barbarous acts that outrage the conscience of humankind." Yet, since the UDHR was adopted to address such acts, there have been significant advances in freedom from state tyranny and human rights.

The content on this page was last updated on .