Summary

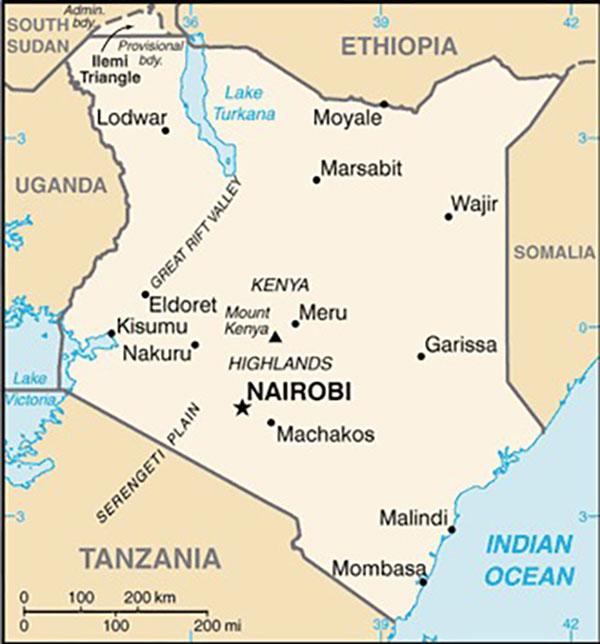

Map of Kenya

Kenya is a presidential republic on the central eastern coast of Africa. It has a multiparty system, regular elections, and some respect for basic freedoms. Its mixed economy, once a model for Africa, today has high levels of poverty and corruption. Freedom House has categorized Kenya as “partly free” since 2004.

Kenya was home to the earliest hominids. In the millennia BCE, Nilotic and Bantu speaking peoples moved to its pastoral lands and remain dominant in the population. Starting in the 1st century CE, Kenya’s coasts were colonized by Arabs. Port cities served as major trading posts. After a period of domination by Portugal from the 15th to 17th centuries, these port cities became part of the Arab Omani Empire.

British colonial rule was established in the 19th century. Kenya achieved full independence in 1964. An early period of democracy was followed by a long period of authoritarian rule. In 2002, a unified opposition (the National Rainbow Coalition) won multi-party elections to regain democratic governance. Since then, there have been changes of government through regular elections but marked by unfair conditions and serious violence. After the 2007 elections, violent ethnic clashes resulted in International Criminal Court charges of crimes against humanity against four Kenyan leaders. Those against the previous and current president were ultimately dropped.

Kenya, with an area of 550 million square kilometers (48th largest in the world), has a population of 55 million people (26th largest in 2023). The population is highly diverse ethnically, with 17 percent Kikuyu, 14 percent Luhya, 13 percent Kalenjin, 11 percent Luo, and 45 percent other groups. Religious affiliation is 85 percent Christian and 11 percent Muslim.

Kenya achieved full independence in 1964. An early period of democracy was followed by a long period of authoritarian rule. In 2002, a unified opposition (the National Rainbow Coalition) won multi-party elections to re-establish democratic governance.

The first president, Jomo Kenyatta, adopted a mixture of free market and state interventionist policies that made Kenya an economic success story. The economy deteriorated under an authoritarian successor. With more democratic governance re-established starting in 2002, the economy has improved somewhat. According to the International Monetary Fund, Kenya's nominal Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2024 is projected to be $104 billion (68th largest in the world). Nominal per capita GDP is projected at $1,983 per annum, improving from 175th in 2006 in the world to 149th.

History

Home to fossil evidence of the oldest known hominid species, much of Kenya’s modern population are Nilotic and Cushitic speakers who migrated from the north in the second millennium BCE. Bantu speakers from the south, whose ethnic groups later dominated politics, arrived later. In the first century CE, migrants from Arab regions established port cities along the coast. The residents there gradually converted to Islam starting in the 8th century CE.

In 1498, the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama, having successfully sailed around the Cape of Good Hope, visited the main coastal city, Mombasa on his way to India. Subsequent explorers seized the port and the Portuguese exercised control over the Kenya coast for much of the 16th and 17th centuries.

Beginning in the 1650s, the ruler of Oman sent naval forces to help free the Muslim city-states. The Portuguese were expelled from Mombasa for the last time in 1729 and the coast enjoyed a relative degree of independence under Omani dynasties until 1832. From then, the Omani sultan of Muscat ruled his empire from the island of Zanzibar (across from Tanzania). He ousted a rival dynasty from Mombasa and secured control over the coast.

Colonization by Great Britain

A thriving slave trade existed in the Omani domain. When the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland outlawed the slave trade in 1807, UK vessels began to suppress the practice in its empire. The Omani ruler of Zanzibar, a British ally, gradually shut down his domain’s slave trade.

Other commerce flourished as European, United States and Indian merchants arrived in large numbers. Christian missionaries and explorers made their way into the interior, beginning the largescale conversion to Christianity by native Kenyans. Competition between the UK and unified Germany led the two powers to delineate spheres of influence in East Africa in 1886 between current Kenya and Tanzania to the south. In 1886, the sultan of Zanzibar transferred his territories on the mainland north of the colonial line to the British East Africa Company. The British government replaced the struggling company in 1895 with an imperial East Africa Protectorate.

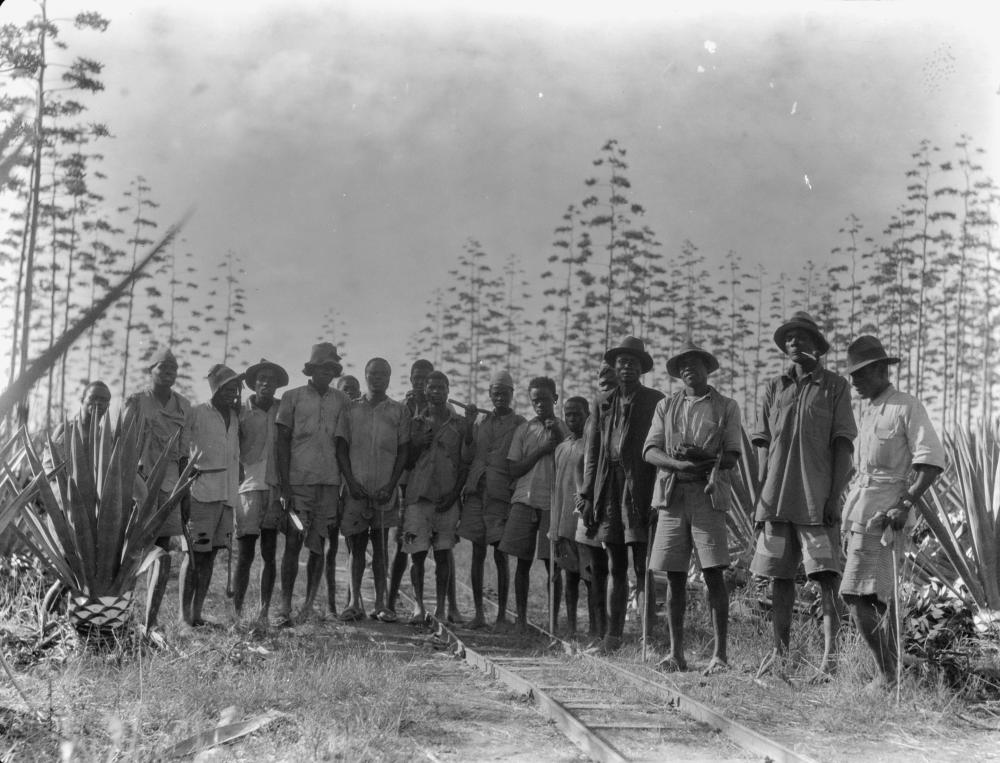

The British government established an East Africa Protectorate, including Kenyan territory in 1895, and encouraged white settlers to farm in Kenya’s interior. They displaced native peoples from their land and then hired them to harvest crops like sisal on plantations. A group of workers is shown above. Public Domain. Library of Congress Prints and Records Division.

In the first decades of the 20th century, the British constructed a railroad from Mombasa to Kisumu on Lake Victoria and encouraged white settlers to begin farming in the highlands of the interior. Their expanding presence met with resistance from the main Bantu-speaking nations, the Kikuyu and Nandi, who were displaced to make way for the settlers. Many were forcibly moved and confined to reserve areas. Since land was typically held by the tribe or ethnic group collectively, British authorities simply granted title to white settlers.

After 1920, the colonial holding was divided into the Kenya Protectorate (coastal areas still nominally the sovereign territory of Zanzibar) and the Kenya Colony (the interior). In the legislative council established for the Protectorate, only white settlers, who numbered 30,000 by the 1930s, could be represented.

Kenya Gains Independence

The first significant indigenous political movement within the Protectorate was the Young Kikuyu Association, begun in 1921. Along with other similar groups, the Kikuyu Association sought African representation in the colonial legislature and improved economic and cultural rights for Africans. These modest demands were resisted by colonial authorities and white settlers.

Pressure continued to mount for decolonialization. Negotiations between the British and a coalition headed by [Jomo] Kenyatta resulted in adoption of a constitution, the holding of initial elections and establishment of dominion status on December 12, 1963.

In 1944, under the banner of the Kenyan African Union (KAU), black Africans gained limited representation in the legislative council. As international and African pressure increased on Great Britain to decolonize after World War II, a Kikuyu insurgent group known as the Mau Mau launched an armed rebellion in 1952. The British colonial authorities responded by declaring a state of emergency and brutally suppressed the Mau Mau rebellion in a four-year military campaign. An estimated 13,000 people were killed, including more than 1,000 by execution. Jomo Kenyatta, the head of KAU, was accused of orchestrating the Mau Mau Rebellion and jailed with other national leaders.

Finally, Britain allowed native Kenyans to elect a majority of members to the Legislative Council in 1957 and form a government, which was headed by the expanded Kenya African National Union (KANU). Jomo Kenyatta was elected its leader after being released from prison in 1961. Pressure continued to mount for decolonialization. Negotiations between the British and a coalition headed by Kenyatta resulted in adoption of a constitution, the holding of initial elections and establishment of dominion status on December 12, 1963.

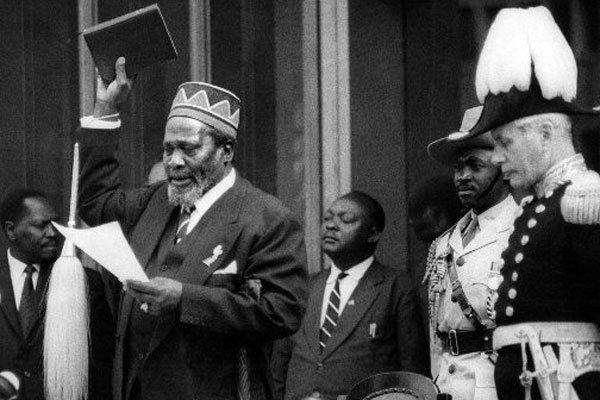

Kenyatta was elected prime minister of an interim government. When the country declared full independence under a new constitution in 1964, he then assumed the office of president. Jomo Kenyatta consolidated power by dispensing privileges and economic favors to members of the country's various ethnic groups. Over time, he used increasingly authoritarian methods to silence critics and potential rivals. Non-Kikuyu leaders were relegated to minor posts. In 1969, Kenyatta banned the main opposition party and Kenya became a de facto one-party state. Further developments are described below.

Kenyans organized to gain representation and independence under the East British Protectorate. In the 1950s, however, British colonial authorities responded to an armed rebellion (the Mau Rebellion) with a brutal military campaign. Above, a memorial to victims of torture from 1952 to 1960. Creative Commons. Attribution: U249601.

Economic Freedom

For the period Kenya was under British colonial administration, its non-coastal economy was dominated by white settlers who owned and operated large estates for agricultural production (mainly coffee) and other purposes. Resistance to the expansion of white settler rule resulted in ethnic groups being forced into natural reserves.

Since independence, Kenya’s economic freedom has been integrally tied to the struggle for political rights and civil liberties.

Since independence, Kenya’s economic freedom has been integrally tied to the struggle for political rights and civil liberties. Kenya’s early independence period under President Jomo Kenyatta was marked by the break-up of large white colonial estates. But the one-party state established in 1969 turned into full-fledged dictatorship under Kenyatta’s successor, Daniel Arap Moi. His rule resulted in widespread poverty and the concentration of wealth and land ownership in the hands of political elites.

The victory of a unified opposition (the Rainbow Coalition Alliance) in multi-party elections in 2002 led to the first peaceful transfer of government power in independent Kenya the next year. But democracy was marred by significant ethnic-based violence and political conflict following the 2007 elections. The 2007–08 crisis was resolved through a unity government and a new constitution. Subsequent elections have been free but marred by fraud.

Above, Jomo Kenyatta takes the oath of office for president in 1964 as Kenya gains full independence from British rule. Rejecting socialism, Kenyatta at first created a model economy that mixed property rights with state-directed investment. Public Domain. Source: Nation Media Group.

Two prominent politicians accused by the International Criminal Court of being directly involved in the ethnic violence following the 2007 elections were elected president and vice president in 2013. Their cases were later dropped when witnesses withdrew their testimony or disappeared.

The economy recovered somewhat under democratically elected governments as Kenya adopted measures allowing greater economic freedom. But issues of land displacement, concentration of wealth and corruption remain salient. Starting in 2013, terror attacks directed from neighboring Somalia resulted in increased police and government abuses, decreased foreign investment and a decline in tourism, one of Kenya’s major industries. The most recent elections, in 2022, were won by an established politician running on an anti-establishment and anti-corruption platform. A detailed account follows.

An Early Economic Model

Instead of nationalizing or seizing the property of white settlers, Kenyatta recognized their property rights and arranged an inventive deal with the British government to finance the purchase of white-owned land for redistribution to Kenyans.

Kenya’s first president, Jomo Kenyatta, rejected socialism as adopted by some post-colonial African leaders and supported the basic legal features of a free-market system as established under British rule. Instead of nationalizing or seizing the property of white settlers, Kenyatta recognized their property rights and arranged an inventive deal with the British government to finance the purchase of white-owned land for redistribution to Kenyans. Many settlers left the country voluntarily, while others stayed and aided in the country's economic growth. Kenyatta’s consensus approach, even with dominant one-party rule, was highly successful and attracted foreign investment. The economy grew at an average annual rate of 6 percent from 1971 to 1981, outstripping most other countries on the continent.

Over time, contradictory economic policies were adopted as Kenyatta became more autocratic. Many poor Kenyans received small farms as part of the land redistribution effort, but large blocks of land went to a privileged Kikuyu elite and later other privileged elites. Despite wide disparities in wealth, most Kenyans did benefit from economic growth. The government also committed a third of the national budget to education and human development.

Authoritarian Rule, Economic Free Fall

Kenyatta, died in office in 1978. He was succeeded by his vice president, Daniel Arap Moi, who plunged the country into dictatorship.

Moi had the constitution amended in 1982 to make Kenya formally a one-party state. The courts and the media became tightly controlled by the government. Political repression intensified. Corruption spread widely throughout government.

Moi had the constitution amended in 1982 to make Kenya formally a one-party state with KANU the only legal political party. The courts and the media became tightly controlled by the government. Political repression intensified. Corruption spread widely throughout government. Moi displaced many of Kenyatta’s favored Kikuyu elite with members of his own ethnic group, the Kalenjin. In a policy called “Africanization,” Moi limited foreign ownership of industry, resulting in a decline in foreign investment and aid. Economic growth rates fell. The economy worsened due to drought and drops in world prices of key agricultural exports (such as coffee). Rapid population growth (from eight million people at independence to twenty-two million in 1988) compounded Kenya’s economic difficulties.

In 1988, Moi instituted the mlolongo (queuing) system of voting by which citizens were forced to line up at the polling station behind the image of their chosen candidate or party to register their vote—a clear violation of a secret ballot. Arrests of democracy advocates sparked mass protests. In 1991, under international pressure supporting the democratic movement, Moi ended the mlolongo system and removed the single-party clause from the constitution.

In 1992 and 1997, Moi claimed victory in multiparty elections amid allegations of electoral fraud. But fraud could achieve only so much. Opposition parties gained 45 percent of the seats in parliament in 1992 and nearly won a majority in 1997. Moi’s policies, meanwhile, kept the economy in a downward spiral. Once an economic success story, Kenya joined the world’s poorest countries.

Democracy Reclaimed

The Rainbow National Coalition united opponents of the Moi dictatorship to win the 2002 elections in a landslide and reclaim Kenya’s democracy. Public Domain.

For the 2002 elections, Moi was barred from running for another term under his own amendments to the constitution. Meanwhile, regional and ethnic-based opposition parties that had emerged since 1992 united into the National Rainbow Coalition (NARC). In presidential elections, NARC’s leader, Mwai Kibaki, handily defeated Moi's handpicked candidate for the Kenya African National Union (KANU). That was Uhuru Kenyatta, the son of Kenya’s first president. In parliamentary elections, NARC routed KANU in both presidential and parliamentary elections. For the first time since independence in 1963, a peaceful transfer of power took place between political parties.

As president, Mwai Kibaki broadened representation in the government, decentralized authority, curbed corruption and generally improved the economy. His policies brought a return of foreign investment. Just two years after the election, however, Kibaki caused a split in the Rainbow Coalition by attempting to change the constitution to further strengthen the presidency.

Several members of Kibaki’s own cabinet formed the Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) to oppose the new constitution. Voters rejected Kibaki’s power grab in a referendum by 57 to 43 percent. But Kibaki’s subsequent actions, especially by again favoring Kikuyu, created more political tensions.

Democracy in Crisis

In the 2007 elections, Kibaki was challenged by Raila Odinga, the leader of the Orange Democratic Movement (ODM). Odinga, an ethnic Luo and son of Kenya’s first vice president, had also risen to prominence as a leading opponent of Daniel Arap Moi.

The 2007 election pitted President Kibaki against Raila Odinga, leader of the opposition Orange Democratic Movement. Amid reports of vote rigging, Kibaki was declared the victor, sparking mass demonstrations and violence that was only resolved in a power-sharing agreement. Above, a rally for Odinga. Creative Commons. Attribution: DEMOSH.

Amid reporting of fraud and vote rigging, Kibaki was declared the victor. The ODM organized protests to call for a new vote. The dispute sparked ethnic conflicts lasting two months that pitted Kikuyu tribal militias backing Kibaki against those of other minority groups (Luo and Kalenjin, among others) backing Odinga. More than 1,200 people were killed and 650,000 people were displaced in the fighting.

In response to the violence, the two leaders came to a power-sharing arrangement. Kibaki was inaugurated as president in charge of the military and foreign affairs; Odinga served in a new position of Prime Minister overseeing domestic affairs. A non-partisan national commission investigated the violence, which appeared to have been planned by political leaders. The parliament ignored the commission’s recommendation for a special tribunal to investigate instigators of the violence. The commission then appealed to UN Secretary-General Kofi Anan to submit individuals it suspected of crimes against humanity to the International Criminal Court (ICC) for investigation.

A Democracy Stabilized But Challenged

The power-sharing government completed a full term of five years. Under a new constitution adopted by referendum in 2010 (with 69 percent of voter support), executive powers were again consolidated but limited. In 2013 elections, Kenyans would now vote for a president and deputy president as head of government; a bicameral parliament (a 337-member National Assembly and a 68-seat Senate); and for governors and assemblies of 47 counties (a new layer of territorial administration dispersing power).

The power-sharing government completed a full term of five years. Under a new constitution adopted by referendum in 2010 . . . executive powers were again consolidated but more limited.

The presidential and legislative terms are for five-years. The president and deputy president are limited to two terms. Two hundred and ninety members of the 337-member National Assembly and 47 of the 68 members in the Senate are elected in first-past-the-post single-member constituencies. Forty-seven seats in the Assembly are reserved for women and determined in separate first-past-the-post elections in the 47 counties. In the Senate, seats are reserved for sixteen women, two youth and two representatives of the disabled community who are selected according to the national party vote.

In 2012, Kenya’s democracy faced a new challenge. After a lengthy investigation, the ICC indicted four persons for crimes against humanity connected to the 2007-08 violence. They were then-deputy prime minister, Uhuru Kenyatta, for financing attacks by Kikuyu gangs; Education Minister William Ruto for orchestrating revenge attacks by Kalenjin militias; a radio executive for inciting violence; and a cabinet secretary.

Free But Marred Elections

In the 2013 presidential contest, outgoing Prime Minister Raila Odinga ran against Uhuru Kenyatta, his deputy prime minister. Despite being previous violent antagonists, William Ruto ran as Kenyatta’s vice presidential running mate. They jointly appealed to citizens to register opposition to the ICC’s interference in Kenyan affairs.

Parliamentary and regional elections were also highly competitive. The Jubilee Coalition, which joined Kenyatta’s and Ruto’s political parties, won a small majority in the National Assembly and Senate.

Kenyatta won with 50.7 percent of the vote, above the 50-percent threshold to avoid a run-off with Odinga, who got 43.5 percent. Ruto also won. Odinga again contested the result but appealed for calm as he presented evidence of electoral fraud. International and domestic observers reported serious irregularities, but the Electoral Commission and Supreme Court each determined that the reported fraud was not sufficient to affect the outcome.

Parliamentary and regional elections were also highly competitive. The Jubilee Coalition, which joined Kenyatta’s and Ruto’s political parties, won a small majority in the National Assembly and Senate. Odinga’s new Coalition for Reforms and Democracy (CORD) won a majority of the gubernatorial races.

Soon after the 2013 elections, Kenyatta and Ruto submitted themselves for arraignment to the ICC and defended themselves in initial proceedings despite the National Assembly voting to withdraw Kenya from the ICC. However, the cases weakened over time with the withdrawal or disappearance of several witnesses reported to be intimidated or bribed. The ICC withdrew the indictment against Kenyatta in December 2014 and the case against Ruto was dismissed in 2016.

New Challenges

As the economy began to recover, the government was confronted with a new challenge. Beginning in 2013, Al-Shabab, an Islamist extremist group from Somalia affiliated to al Qaeda, carried out ongoing terror attacks. Al-Shabab hoped to end Kenya’s lead involvement in an African Union peacekeeping force in Somalia that had removed its terror group from strongholds in the capital and other cities. The worst attack was at a major university in April 2015 in which a total of 147 people were killed. Foreign investment declined due to the terror attacks as did Kenya’s tourism industry.

Al-Shabab, an Islamist extremist group from Somalia affiliated to al Qaeda, carried out ongoing terror attacks. . . . The National Assembly passed a new Securities Law in 2014 that gave the government broad powers of surveillance, search and seizure and long-term detention without charge.

The National Assembly passed a new Securities Law in 2014 that gave the government broad powers of surveillance, search and seizure and long-term detention without charge. Human rights organizations documented extrajudicial murders, disappearances and torture. Refugees from Somalia were rounded up and forced into crowded camps. Many were deported on grounds of “emergency security.”

The marred 2013 elections led to a concerted effort by Raila Odinga and CORD (the Coalition for Reforms and Democracy), to reform the Internal Boundaries Electoral Commission (IEBC), which oversees national elections. An effort to adopt constitutional amendments failed when the Supreme Court invalidated nearly half the 1.6 million signatures gathered for a referendum, preventing the amendments from being presented to voters. Still, large weekly protests in 2014 and 2015 succeeded in gaining equal party representation on the IEBC in advance of the 2017 elections.

Current Issues

Since 2004, Freedom House has consistently categorized Kenya as “partly free,” around the midpoint of the 100-point scale. Having overcome a period of harsh authoritarian rule, Kenya’s multi-party democracy has had regular transfers of power since December 2002 but the country has struggled to establish effective governance or achieve justice for victims of ethnic violence, especially from the 2007-08 crisis. Since then, however, its leaders demonstrated a capacity for resolving conflicts through political agreement. Citizen engagement is high in trying to improve political, social and economic conditions. Free media have become more assertive.

Kenya’s economy was brought back from a freefall under authoritarian rule. Uhura Kenyatta’s governments achieved growth averaging between 5 and 6 percent, returning Kenya to the level at least of the developing world. Freedom House’s ranking for freedom from exploitation improved to 2/4 from 1/4 in 2018. Still, income and wealth disparity are high, per capita income remains low and most Kenyans struggle to make a living from the land or in commerce.

The Heritage Foundation, meanwhile, ranks Kenya as “mostly unfree” in its 2023 Economic Freedom Index (135th of 176 ranked countries) due to what it judges as excessive regulations, weak rule of law and corruption. A conservative Canadian counterpart, the Fraser Institute, ranks Kenya higher (78th out of 165 countries) based on its underlying free market conditions.

William Ruto emerged as the opposition candidate in the October 2022 presidential elections leading a new alliance, Kenya First, which also won a working majority in parliament. Seen here on the right meeting with US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin at the Kenya State House in Nairobi in September 2023. Public Domain.

The 2017 elections again pitted Jomo Kenyatta, running for a second term, against Odinga, running for a new coalition, the National Super Alliance (NASA). Kenyatta, with running mate William Ruto, won the first round in August with 54 percent of the vote. Odinga again contested the outcome.

In this case, the Supreme Court agreed that the evidence presented of fraud, intimidation and violence was sufficient to invalidate the results. It ordered a new election for October. But Odinga and NASA withdrew and urged a boycott given that no new protections for a fair process were put in place. Kenyatta won with 98 percent of the vote. His Jubilee Coalition again won narrow majorities in the National Assembly and Senate but also now a majority of governorships and regional assemblies.

The lack of legitimacy for the election led to a continuing political crisis that was resolved only by a famous public handshake of Kenyatta and Odinga. The two agreed to a process (the Building Bridges Initiative) for proposing constitutional reforms for addressing political, economic and social inequities.

The lack of legitimacy for the election led to a continuing political crisis that was resolved only by a famous public handshake of Kenyatta and Odinga. The two agreed to a process . . . for proposing constitutional reforms for addressing political, economic and social inequities.

“The handshake” was viewed by many opposition politicians less as a means of conflict resolution and more as a betrayal by Odinga for future power. The Supreme Court agreed, rejecting constitutional amendments passed by the National Assembly that seemed to benefit the Kenyatta-Odinga alliance.

For the 2022 presidential election, Odinga now received the endorsement of Kenyatta, who was prevented from a third term. The Jubilee Coalition joined Odinga’s adherents in a new One Kenya Alliance.

William Ruto, however, still serving as deputy president, now emerged as a formidable opposition candidate. His United Democratic Alliance joined with other parties, many from the previous Rainbow Coalition and CORD opposition groups, to form Kenya Kwanza (Kenya First).

One Kenya Alliance and Kenya Kwanza both adopted progressive platforms but Ruto also ran on an anti-establishment and anti-corruption platform as an “outsider” and “hustler” against fixed political arrangements of dominant elites. Appealing to youth and marginalized groups, Ruto won election by a narrow margin, 50.4 percent to 48.5 percent for Odinga.

While Odinga’s One Kenya won a plurality in the National Assembly (173 seats), Ruto’s Kenya Kwanza alliance parties obtained a working majority in both the 350-seat National Assembly and 68-seat Senate. Odinga’s allies on the IEBC objected to the presidential result and resigned, but the IEBC chairman affirmed the outcome and international observers testified to an overall free and fair process. The Supreme Court upheld the result.

Among one of Ruto’s anti-corruption promises was releasing previously hidden terms of loans for Chinese-funded infrastructure projects. The first documents, released in November 2022, were for the $4.7 billion Standard Gauge Railway, signed in 2014. The Standard Gauge Railway is one of many large infrastructure projects with China that have made it Kenya’s largest trading partner and also saddled Kenya with large debt. Originating in Mombasa, the railway has no clear final destination and is over-budget (see article in Resources). The Supreme Court declared the project illegal due to corrupt sourcing contracts.

Ruto’s presidency, however, has also been marked by turmoil. In 2023, the One Kenya coalition of Raila Odinga organized a series of large disruptive protests. Those organized in July resulted in clashes between security forces and protesters in several cities with 30 killed and 300 arrests total. The events led to talks between leaders of One Kenya and the ruling United Democratic Alliance coalitions, Odinga and President Ruto. They agreed to create a National Dialogue Committee, which made a report recommending a review of the 2022 presidential election and reconstitution of the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission.

In June 2024, massive protests of youth erupted over Ruto’s proposed bill for tax increases to solve Kenya’s growing debt crisis. The taxes were seen as regressive at a time of a cost-of-living crisis for most Kenyans. When demonstrators stormed the parliament after passage of the bill, security forces and protestors clashed, resulting in 22 deaths and many more injuries. The next day, Ruto announced that he would not sign the bill, but there are disturbing reports of security forces carrying out extrajudicial killings. In the aftermath, young people have emerged as a more organized force in Kenyan politics.

Among the anti-corruption promises President Ruto made was releasing hidden terms of loans for the Standard Gauge Railway, one of many infrastructure projects with China. Originating in Mombasa on the coast, the railway remains unfinished and was fraught with illegal sourcing contracts. Creative Commons. Photo by: Daniel Syengo.

The content on this page was last updated on .