Introduction

In a democracy, the principle of accountability holds that government officials are responsible to the citizenry for their decisions and actions and that they act in the public interest, not their self-interest.

In a democracy, the principle of accountability holds that government officials are responsible to the citizenry for their decisions and actions and that they act in the public interest, not their self-interest. In order to hold officials accountable, the principle of transparency requires that the decisions and actions of those in government be open to public scrutiny and that the public has a right to access information about how government decisions are made and carried out. Both concepts are essential principles to democratic governance.

Free elections (see previous section) are the primary means for citizens to hold their country's officials accountable. This is the case especially when such officials have abused power or behaved illegally, corruptly or ineptly in carrying out the people’s work. But, given their power in office, it is necessary also to hold elected or appointed officials accountable in between elections. This is done through votes of no confidence (in parliamentary systems), impeachment (in presidential systems), and public investigations. Public pressure or sentiment due to the media’s uncovering of misdeeds, a public investigation, or a criminal investigation generally serve to compel officials to change policies, reverse decisions or resign their offices prior to formal recall or impeachment.

Without accountability and transparency, democracy is impossible. In their absence, electoral choices and elections lose their meaning as an expression of the people’s will.

In this way, accountability and transparency help create better policies, improve public services and stop the abuse of power. The more the public knows about policy decisions and governmental actions, the better its elected representatives can make public policy choices and ensure that the common or general interest is served. Without accountability and transparency, democracy is impossible. In their absence, electoral choices and elections lose their meaning as an expression of the people’s will. Government becomes arbitrary and self-serving and policies benefit the ruling elite, not the people.

The Role of Free Media

James Madison embedded a free press in drafting the Bill of Rights. A 1958 US postage stamp celebrating the First Amendment.

James Madison, the principal author of the Bill of Rights, asserted that the very basis for government's responsiveness to the people was the assurance that citizens have sufficient knowledge to direct it. If citizens are to govern their own affairs through direct or representative government, then they must have access to the information needed in order to come to informed opinions on policies and make informed choices for elected representatives determining those policies. If voters and their representatives are not informed, they cannot act in their own interest or in the common interest.

For this reason, Madison was convinced to embed the protection of a free press from government interference in the First Amendment to the Constitution as an essential guarantor of the public's access to knowledge. In the United States, as well as in most established democracies, the free press has broad protection from government interference in its rights and responsibilities to inform the public. Consequently, journalists have the freedom to search out information when the public interest is concerned and the media may publish or broadcast information and opinion relevant to the public interest (see also History in this section and Freedom of Expression). When governments restrict the free press, leaders become less accountable.

The People’s Right to Know

The right to know also includes transparency of government so that the public can be aware of the decisions made, how they are made, and how government carries out those decisions.

The right to know also includes transparency of government so that the public can be aware of the decisions made, how they are made, and how government carries out those decisions.

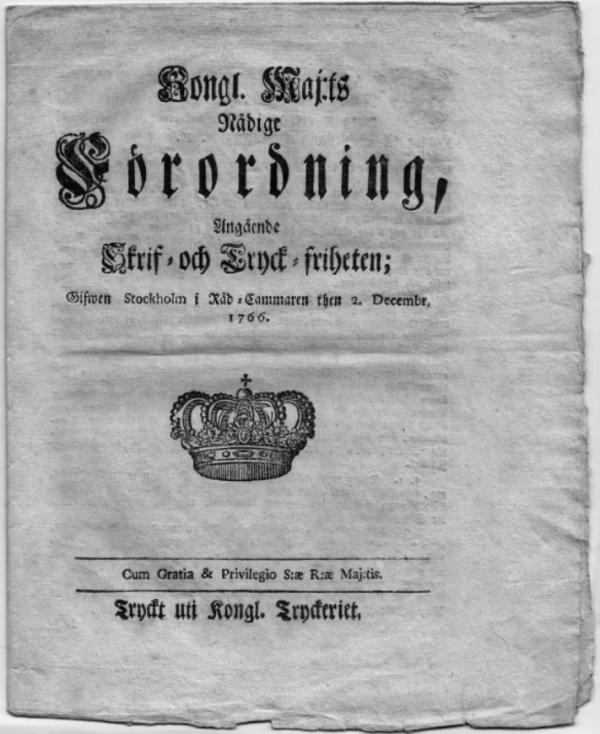

The first law establishing the right of a free press and open government was the Freedom of Press Act in Sweden in 1766, although the Act was reversed following a coup d’état. The right to know was also made foundational in parts of the US Constitution, adopted in 1788. Its provisions require, among other things, that the proceedings of Congress be published regularly and that the president report regularly on the “state of the nation” and its annual expenditures (see History). The French Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen provided that “The society has the right of requesting an account from any public agent of its administration” (Article 15).

A copy of the 1766 Freedom of Press Act in Sweden, the first such law guaranteeing a free press. It was reversed after a coup d’etat and not fully re-enacted until 1949.

Still, the principle of the citizens’ right to know developed slowly and did not become standard practice until after World War II. Sweden re-enacted its Freedom of Press Act in 1949, with requirements for access to information. In the United States, the right to access government information was entrenched in the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) in 1966 (see History). In France implementing language for Article 15 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen was adopted only in 1978. Today, most democracies have adopted similar “right to know” or “sunshine” laws, as well as open meetings acts and protections for whistleblowers (those within government who reveal illegality, violations of rules and regulations, or malfeasance to the public).

Separation of Powers

Accountability also involves the separation of powers, which is the principle that no branch of government may dominate and that each branch has checks on the abuse of power by other branches.

Accountability also involves the separation of powers, which is the principle that no branch of government may dominate and that each branch has checks on the abuse of power by other branches (see also Constitutional Limits).

In parliamentary systems, the legislature’s power to withdraw majority support through votes of no confidence hold governments to immediate account, most often by triggering a new election. By contrast, presidential systems rely on impeachment, investigations and public pressure as mechanisms in between elections to address malfeasance, abuses of power and loss of confidence in the elected government. In both systems, standards of accountability are also established through tradition and laws, an independent judiciary to enforce them, legislative oversight and free media.

Federalism, which is practiced in some countries, offers additional separation of powers by delegating to states or regions matters of governance not made at the national level. A similar principle is subsidiarity, found in the laws of the European Union (EU), which requires that decisions be made at the lowest level of government possible. Federalism and subsidiarity may conflict with protecting rights or setting national priorities but also establish more local accountability for decisions directly affecting the citizenry.

The Advantage of Democracy

The level of corruption ─ the abuse of positions of power or privilege for personal, corporate or group enrichment or benefit ─ is a general indicator of whether a government is accountable and serving the needs of the people.

The level of corruption ─ the abuse of positions of power or privilege for personal, corporate or group enrichment or benefit ─ is a general indicator of whether a government is accountable and serving the needs of the people. Democracies are not immune from corruption, but they have several advantages in dealing with it.

One is that elected representatives have a direct relationship with the country's citizens through free elections. As well, constitutional provisions and laws related to elections and governance reflect the idea that those who work for the government ─ whether elected, appointed or hired ─ owe a high level of accountability to the people.

Democracies generally enact anti-corruption statutes and ethical rules, often in direct response to officials using their offices for private enrichment or being bought to serve privileged interests through campaign contributions or direct bribes. Democracies also establish ethics offices and ombudsmen (or, as in the United States, Inspector Generals) to ensure compliance with these statutes and ethical guidelines. Legislative oversight and independent commissions may also act to investigate malfeasance.

One check on corruption is independent law enforcement and judiciary acting to enforce the laws. An example of that in the United States was the case of Spiro Agnew, the vice president for Richard Nixon. One year ahead of Nixon’s own resignation due to the Watergate scandal (see below), Agnew resigned in 1973 rather than face imprisonment for corrupt paybacks that began when he was a county executive in the state of Maryland. Prosecutors and investigators had found that those paybacks continued while he was governor and even as vice president (see Resources).

The Disadvantage of Dictatorships

Authoritarian systems on the other hand tend to be unaccountable and encourage public corruption. Dictators generally embed corruption within the governing system, encouraging national and local officials to abuse power through the taking of bribes.

Authoritarian systems on the other hand tend to be unaccountable and encourage public corruption. Dictators generally embed corruption within the governing system, encouraging national and local officials to abuse power through the taking of bribes. This is done both as a means to control the citizenry and also to engender the loyalty of officials by providing them a personal stake in perpetuating an authoritarian system of rule.

The correlation of dictatorship and corruption is clear when comparing the Freedom in the World survey of Freedom House with the “Corruption Perceptions Index” compiled by Transparency International, a global organization committed to fighting corruption. Of the fifty most corrupt countries and territories surveyed in Transparency International’s 2022 index, thirty-nine are ranked “Not Free” and eleven as “Partly Free” in Freedom House’s 2022 survey. Of the fifty least corrupt countries and territories, forty-four are rated "Free," four are "Partly Free," and only two are "Not Free."

The Abuse of Power

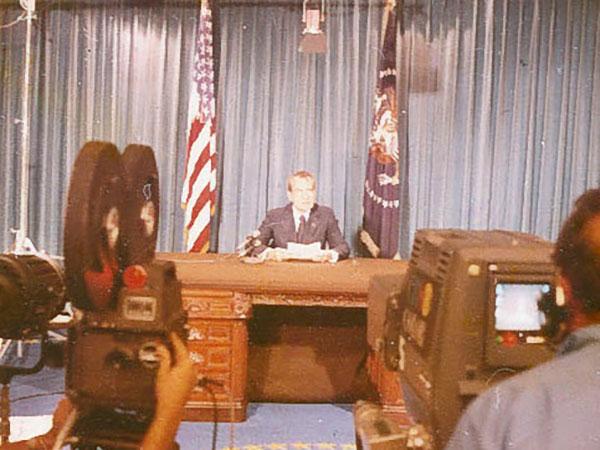

US President Richard Nixon, facing impeachment and conviction for abusing power, resigned the presidency in an Oval Office address to the nation on August 8, 1974.

As with corruption, democracies must confront the problem of abuses of power. This includes misuse of authority to enhance or maintain public office by extra-constitutional means, to serve personal or foreign interests, to repay election donations with political favors or to engage in disreputable behavior.

But as with corruption, democracies often confront abuses of power where dictatorships do not. In the United States, for example, the abuse of power by President Richard Nixon in the early 1970s was confronted by many of the instruments listed above as necessary for accountability: free media, legislative and law enforcement investigations, an independent judiciary and public pressure (see History for a fuller account of the Watergate scandal).

[M]ost dictatorships, are fully “captured states.” Constitutional mechanisms against abuse of power are toothless; media is under state control or domination; political parties are submissive; and public dissent is repressed.

A more recent case is South Africa. Media exposés and legislative inquiries prompted independent investigations, as required under provisions in the constitution. These revealed wide-ranging corruption and abuse of power by President Jacob Zuma with the aim to achieve what political scientists call “state capture.” Zuma was forced to resign in 2018 (see Country Study).

While democracies confront ongoing challenges of abuse of power (as recounted in the History section), most dictatorships, are fully “captured states.” Constitutional mechanisms against abuse of power are toothless; media is under state control or domination; political parties are submissive; and public dissent is repressed. There is no possibility to confront abuse of power outside of citizen rebellion.

The Abuse of Power (continued)

In dictatorships, establishing and maintaining control over police and security forces is a first order of business to seize and hold power.

A key measure in Freedom House’s Survey of Freedom is public accountability for police behavior.

Throughout history, abuse of power and authority by police or security forces has been a defining characteristic of dictatorships. Police and security forces (including anti-riot police, presidential guards and border units) are the primary instrument of dictatorships for maintaining control of the citizenry and suppressing protest against repressive rule. In dictatorships, establishing and maintaining control over police and security forces is a first order of business to seize and hold power.

Maintaining loyalty and subservience within police and security forces is thus key for autocrats. When loyalty to the ruler or a ruling party weakens, police forces sometimes have refrained from suppressing mass protests for democratic change and popular rule. An example is the Philippines “People Power” democracy movement in 1986 (see Country Study in this section).

Control of security and police forces is a first order of business for dictatorships. Above, police deployed against civilian protests in Kazakhstan in January 2022 (see Country Study in this section). Shutterstock. Photo by Vladimir Tretyakov.

In democracies, police or peace forces are supposed to be servants of the community, not of one ruler or party. Yet, the nature of policing is to maintain law and order, so on some level to control the citizenry. Such power can often lead to abuse of power and lack of accountability also in democracies, especially toward marginalized or minority communities. When political power is centralized in localities or regions, police power can be wielded in dictatorial fashion. This was the case in many states in the United States during the periods of both slavery and Jim Crow (see also History section in Majority Rule, Minority Rights).

Establishing and enforcing basic standards of accountability for police to prevent abuse of power is thus an ongoing challenge in all democracies. This was seen recently in both the domestic and international response to the police murder of George Floyd in 2020 (see, for example, Country Studies of France, and Netherlands). Some democracies have greater success than others.

Representative and Private Institutions

In democracies, standards of accountability and transparency also apply to businesses, groups and organizations that operate under public laws, including volunteer organizations and trade unions.

When one speaks of corruption in this context, it usually involves embezzlement of funds or the payment of bribes to government officials to obtain special treatment. It also involves the corrupting and corrosive impact of private interests on elections and how this affects policy and laws (see History in this section and in Free Elections.)

Democracies generally adopt laws that require corporate, civic or private representative institutions to conduct themselves in a manner ensuring that the interests of stakeholders, members, and the general public are properly served and that the public's trust is not violated. A measure of democracy’s well-being is the degree to which such institutions are held accountable.

In dictatorships, private businesses or organizations may exist but often they become instruments of the state and are used to enrich rulers, benefit close associates and control the broader society.

International institutions have established universal standards designed to prevent corruption in such private institutions serving the public. These include the United Nations, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the Council of Europe. The United States has supported the Open Government Partnership. It provides data on the way public money is spent through private institutions (see Resources).

In dictatorships, private businesses or organizations may exist but often they become instruments of the state and are used to enrich rulers, benefit close associates and control the broader society. Some organizations may be under less control but still limit or modify their behavior so as not to antagonize ruling authorities. Trade unions are a particular target for control by an authoritarian government or party in power so as to prevent worker unrest (see, for example, Country Studies of Cuba and Poland).

Accountability for Genocide, War Crimes & Crimes Against Humanity

The total war, criminality and scale of violence perpetrated by Nazi Germany and other Axis powers during World War II, together with the unprecedented crime of the Holocaust, made clear the necessity for a new international system of accountability.

Throughout history, there has been little accountability for the largest abuses: crimes of aggression, war crimes and crimes against humanity. As well, there are few instances of justice or formal reparations for chattel slavery, confiscation of territory from Indigenous communities or crimes committed by colonial regimes. (When Britain and France abolished slavery, for example, compensation was generally given to slaveholders, not freedmen and freedwomen.)

The total war, criminality and scale of violence perpetrated by Nazi Germany and other Axis powers during World War II, together with the unprecedented crime of the Holocaust, made clear the necessity for a new international system of accountability.

A first precedent was established by the Nuremberg and Tokyo war crimes trials of the Allied victors in the war. These were ad hoc proceedings that took place from 1945 to 1948. For the first time, individual leaders and officials were found accountable for crimes initiated by states. Formal trials with rules of evidence and due process were conducted for the crime of aggression, war crimes and crimes against humanity carried out by Germany’s Third Reich and Japan. The trials resulted in hundreds of convictions and punishments, including the death penalty for individuals who specifically carried out these crimes (see Resources and also Rule of Law).

The ad hoc Nuremberg and Tokyo War Crimes Trials established a precedent for prosecuting individuals who perpetrated crimes against humanity and war crimes on behalf of nation states. Above is a picture of defendants in one of the Nuremberg Trials, the Major Trial of 24, in 1946. Public Domain. National Archives.

The UN Charter, adopted in 1945, and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, both adopted in 1948, further established that no government is above the universal laws of nations. Under these documents, the international community may act to prevent and hold accountable states, leaders and officials for acts of genocide, wars of aggression, crimes against humanity and the gross violation of human rights.

A UN Commission on Human Rights (now called the UN Human Rights Council) was established to monitor compliance with the UDHR and other human rights conventions. The UN Security Council was given authority to adopt sanctions and act against aggression and other violations of international law. However, no permanent institutions ensured that states fully adhered to these international principles. Mass repression, ethnic cleansing, acts of genocide and wars continued to occur without effective international responses in many cases due to the governing structure of the UN system, and specifically the veto power of permanent Security Council members.

In the 1990s, the UN Security Council authorized special tribunals to prosecute war crimes and crimes against humanity in the former Yugoslavia, Rwanda and other countries in which genocide and crimes against humanity occurred in the 1990s. In 2002, the Rome Convention, held under UN auspices, established the International Criminal Court (ICC) to investigate member countries and prosecute individuals accused of these and other violations of international law. (There are currently 123 member states to the Rome Convention but the United States is not a signatory.)

The ICC has taken action to indict and try a number of government leaders in the last two decades. Recently, it indicted Russian Federation President Vladimir Putin and another Russian official for the crime of genocide in Ukraine. It has also indicted leaders of the Hamas terror group for its attack on Israel on October 7, 2023 as well as Israel’s Prime Minister and Defense Minister for war crimes committed subsequently in Israel’s war against Hamas.

Some individual states adopted the judicial principle of international jurisdiction that allows them to prosecute war crimes and crimes against humanity in domestic courts even when committed in other countries. Germany, Spain, the UK and, to some extent the United States, among others, have adopted this principle.

Through all of these institutions and practices, the hope is that violators of basic international standards are brought more to justice and thereby that future international crimes may be deterred (see also History). There remains ongoing debate on the ultimate effectiveness of such processes in deterring criminal international behavior. But the trend is clear towards pursuing cases in international, domestic and foreign courts for the purpose of holding individual leaders and officials accountable for genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity.

The content on this page was last updated on .