Summary

Map of Botswana

Botswana is Africa’s oldest continuous multiparty democracy, having held uninterrupted free elections since gaining independence in 1966. Freedom House has categorized Botswana as “Free” since its first Freedom in the World survey in 1973.

A landlocked country in southern Africa, Botswana came under British protectorate status with indirect administration in the late 19th century. It gained local self-rule in the 1950s and independence in 1966.

Botswana has a parliamentary system. Its president, who nominates and administers the government, is elected by the ruling party in parliament. The country's political, legal and economic institutions are generally open and there is a strong record of respect for human rights, rule of law and government accountability. Until recently, its politics were dominated by the Botswana Democratic Party (BDP), which led the country to independence. However, opposition parties functioned freely. In the 2024 elections the BDP lost its parliamentary majority for the first time in 57 years to the United Democratic Congress (see Current Issues).

Transparency International consistently ranks Botswana as among the least corrupt countries in Africa and in the world, although its ranking dropped in recent years (43rd out of 180 countries and territories in its 2024 Corruption Perceptions Index). The World Justice Report’s 2024 Index on Rule of Law places Botswana the score’s midrange (.59 out 1.0), but still second highest among African countries.

Botswana is Africa’s oldest continuous multiparty democracy, having held uninterrupted free elections since gaining independence in 1966.

Botswana, bordered by Angola, Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe, is moderate in size (ranked 45th in the world at 600,370 square kilometers). Botswana is also among the world’s least densely populated countries with around 2.5 million people (2025 UN estimate). The national economy, dependent on diamond mining, has a projected 2024 Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of $21 billion, ranking 122nd in the world according to the International Monetary Fund. Nominal GDP per capita ($7,875 per annum) is ranked higher (88th in the world and 4th highest in Africa). Botswanans boast among the continent’s highest literacy and education rates (87 percent), but income inequality remains significant.

History

Origins and Development

Botswana's original inhabitants lived on its general territory from approximately 17,000 BCE to 1650 CE. During the earliest period, groups subsisted through hunting and gathering and turned toward animal herding during the last few centuries BCE. The original language group was Khoisan, spoken by both Khoisan and San ethnic groups. In the last centuries BCE, Bantu-speaking tribes migrated from the north to the southern part of the continent, bringing with them the farming of grain crops.

The Tswana people, Bantu speakers living in what is currently Botswana and South Africa, established a powerful dynasty in the 13th and 14th centuries CE. Over time, the Tswana divided. Those living in South Africa continued to be known as Tswana; those in the north were known as Batswana. (Both groups retained a common language, Setswana.) Batswana came to be used to refer to all people living in Botswana regardless of ethnicity.

Conflict with the Boer and British Colonial Rule

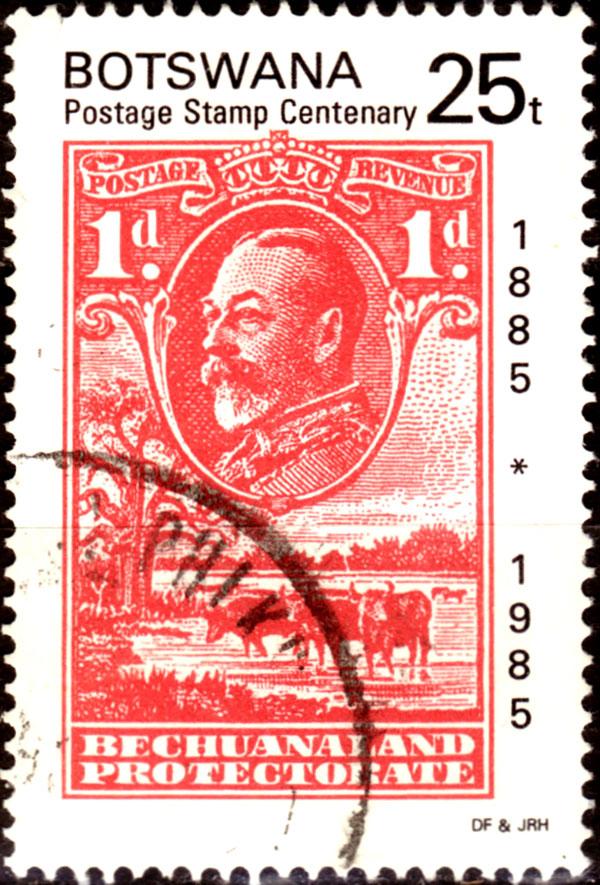

Bechuanaland, now named Botswana, came under a British protectorate in 1885. A joint British-Botswana 1985 postage stamp commemorating the centenary.

In the 1820s, British explorers and missionaries Robert Moffat and David Livingstone landed to establish religious settlements among the Batswana to convert the local communities to Christianity. (Approximately 70 percent of Botswana's citizens today are Christian.) In that time, different Batswana groups came into conflict with both the Boer (white Dutch settlers escaping British administration of the Cape Colony) and the Zulu and Ndebele nations, who were expanding their territory (see also Country Study of South Africa).

In 1876, under threat of resumed hostilities with the Boer, the dominant leader of Batswana, Chief Khama III, appealed to the British government to take their lands under British protection. In agreement with Khama III and other chiefs, the northern territory was proclaimed a British protectorate in 1885. It was named Bechuanaland, while the southern territory (currently South Africa) was absorbed into the Cape Colony. In general, since Bechuanaland fell under indirect administration, the British colonial period was less harsh than in South Africa. Local law and customs were applied in most matters.

The Evolution to Independence

Independence leader Seretse Khama, the grandson of Chief Khama III (the leader of the protectorate of Bechuanaland), in 1961.

Demand for government services led to the creation in 1920 of two advisory councils, one for Africans and one for Europeans. The goal was to give Bechuanaland's chiefs more direct access to British administration. In 1934, British authorities also regularized tribal powers and rule. Among British colonies, Botswana had a more peaceful path to independence (by contrast, see Country Studies of Malaysia and Kenya). In 1951, the British initiated a process of self-determination by establishing a joint African-European advisory council. In 1959, a constitutional committee was formed. This was followed by the election of a legislative council in 1961 and adoption of a national constitution in 1965. Independence was declared on September 30, 1966, with the country’s capital in Gaborone.

Democracy With One-Party Dominance

The main political force in the country, both before and since independence, has been the Botswana Democratic Party (BDP). It has won a majority of seats in parliament since 1966. Independence leader Seretse Khama led the BDP to its first election victory in 1966 and in two subsequent victories in 1971 and 1976.

The main political force in the country, both before and since independence, has been the Botswana Democratic Party (BDP). It has won a majority of seats in parliament since 1966.

The National Assembly, which selects the president for a four-year term (similar to its own), chose Khama three times. He decided to resign just before the end of his last term in 1980 to give the vice president, Quett Masire, the advantage of incumbency. Masire also was elected three times by parliament and resigned similarly in 1998 before his final term ended. Festus Mogae, the vice president, served out the term and was elected president by the National Assembly in 1999 and again in 2004.

In 2008, Mogae continued the practice of resigning, but before completion of his second term. He was succeeded by Vice President Seretse Khama Ian Khama, the son of Botswana’s independence leader. While the practice was initiated by Seretse Khama to ensure a peaceful transfer of power, Mogae’s resignation gave rise to criticisms from a growing opposition that the ruling party was trying to rig the system. As in previous elections, the Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) maintained a decisive edge in 2009, winning 53.3 percent of the vote and 45 of 57 elected seats. The new National Assembly confirmed Ian Khama for a full presidential term.

Ian Khama (center), the son of Botswana’s independence leader, at the 2014 London Conference on the Illegal Wildlife Trade with other African leaders. Open Government License. Foreign and Commonwealth Office.

The main opposition party since 1969 was the left-leaning Botswana National Front (BNF), which had a social democratic profile. In the 2009 elections, it won six seats, down from 12 in 2004, while a splinter party, the Botswana Congress Party (BCP), took four seats. Two newer parties captured one seat each. International observers deemed the elections free and fair. In more recent elections, the opposition has become more competitive (see below).

Accountability and Transparency

Botswana has the longest period of uninterrupted free elections and democratic parliamentary rule in Africa. Its government generally respects human rights and the rule of law and has among the most developed accountability mechanisms on the continent.

Botswana has the longest period of uninterrupted free elections and democratic parliamentary rule in Africa. Its government generally respects human rights and the rule of law and has among the most developed accountability mechanisms on the continent. At the same time, the long-term dominance of the political system by the Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) led to a concentration of political power, government abuse and corruption, and attempts to limit free media. As a result, opposition parties gained strength in the 2014 and 2019 elections. In the 2024 elections, as the economy suffered from declining worldwide sales in diamonds, the country’s chief export, the BDP lost its parliamentary majority for the first time to the longtime opposition grouping, the United Democratic Congress. Botswana’s constitutional system and political history are described below. More recent events are recounted in Current Issues.

A Parliamentary Democracy Based on Consensus Building

A 65-member National Assembly has dominant legislative powers in a bi-cameral parliament. The electoral mandate is five years, but the National Assembly may be dismissed, or its mandate prolonged, by order of the president. Fifty-seven seats are elected by constituent districts in a “first past the post” system. Six seats are filled by the president but his candidates must be approved by the National Assembly’s elected members. The president and Attorney General are ex-officio members.

The president is elected to a five-year term by parliament. He is head of state with executive power, including over security agencies. Until 2024, the president was always the leader of the majority party, the Botswana Democratic Party (BDP), which had led Botswana to independence. It is currently the leader of the Umbrella for Democratic Change, which won the 2024 elections. The vice-president is appointed by the president and approved by the National Assembly.

Parliament’s second chamber, with 34 members, is an advisory body called the House of Chiefs. It has representatives of the country's eight major Setswana-speaking groups (making up 80 percent of the population) as well as of smaller ethnic groups. The chamber ─ as the overall political system ─ tends to marginalize smaller ethnic groups. This is especially the case for the San, the territory’s Indigenous inhabitants, who are 3 percent of the population.

Botswana has held free and fair elections since independence in 1966. The Botswana Democratic Party has won majorities in parliament in all but one of them. A BDP campaign poster. Shutterstock. Photo by Herb Klein.

The BDP’s longstanding support since independence in both houses of parliament was based on the eight major Setswana-speaking groups, which have their own ruling traditions. These include limits on the power of traditional leaders, local consultative assemblies, consensus decision making and accountability measures.

Botswana's presidents incorporated the consensus tradition into their style of leadership and thus incorporated accountability mechanisms and acted to limit government corruption (see below). Recent presidents, however, exhibited a more dominant style. Due to increasing public concerns about a concentration of power and corruption, the BDP lost its majority in parliament for the first time in 2024 (see Current Issues below).

Fiscal Accountability and Anticorruption Powers

Botswana's constitution and legislation require accountability and some measure of transparency, although it still lacks a freedom of information law.

Botswana's constitution and legislation require accountability and some measure of transparency, although it still lacks a freedom of information law.

The constitution specifies duties of the Office of the Auditor General, who is required to conduct an annual audit of all public accounts. This includes expenditures of office-holders, the courts, and partially owned government entities known as parastatals. The auditor general is appointed by the president with a fixed term and cannot be removed from office. Audits are presented to the National Assembly by the minister of finance, but the auditor general may also report directly to the Assembly Speaker.

Botswana's Finance and Audit Act specifies that the auditor general must ensure the collection and custody of public funds and that funds are disbursed with proper legislative authorization and according to legislative intent. This requirement is particularly important due to the economy’s dependence on diamond mining, Botswana’s primary resource. The government is required to build up a high level of foreign reserves to safeguard the budget in cases of drops in the commodity price for diamonds, and also to prepare for the future decline in production (diamond reserves will be exhausted likely by 2050).

In addition to extensive public accounting, which is public information, the government passed a bill in 1994 that set up an anticorruption body with the powers to conduct investigations and make arrests. There have been regular arrests and convictions of government officials for corruption. The acquittal of some high-level ministers, however, gave rise to fears of government interference in the traditionally independent judiciary (see Current Issues).

Botswana's laws establish civilian supervision over the police and an ombudsman who acts on civilians’ complaints regarding police abuse or other human rights violations.

Botswana's laws establish civilian supervision over the police and an ombudsman who acts on civilians’ complaints regarding police abuse or other human rights violations. Despite these mechanisms for public accountability, there is no freedom of information law to ensure transparency. This lack allowed the government to maintain secrecy in many matters and limited the effectiveness of the office of ombudsman.

Human Rights

The constitution of Botswana guarantees freedom of expression. There is a free and vigorous press and independent private broadcast networks (this includes one television channel and two radio stations).

The government generally respects media freedom. Strong critiques of the government appear in the press, on private outlets and on the state broadcast network. In 2008, however, the National Assembly passed the Media Practitioners Act establishing a media regulatory body and registration of all media workers and outlets. Under the Act, which was upheld by the High Court, the government censored coverage it deemed inappropriate and prosecuted individuals for insulting the president.

The most significant case of media freedom was the 2014 arrest of Outsa Mokone, the editor of Botswana’s leading independent newspaper, The Weekly Standard. President Ian Khama directed the arrest. Mokone, was charged with violating the sedition law for articles revealing a cover-up of a high-speed crash involving the president’s detail. The newspaper also had run a number of articles about corruption within the new intelligence directorate (see below). The charges were finally dropped in 2018, but according to Freedom House the case against Mokone had “a chilling effect” on reporting.

The most significant case of media freedom was the 2014 arrest of Outsa Mokone, the editor of Botswana’s leading independent newspaper, The Weekly Standard. . . . [He} was charged with violating the sedition law for articles revealing a cover-up of a high-speed crash involving the president’s detail.

Freedom of association and assembly are also respected. In a landmark 2014 ruling, for example, the Botswana High Court ordered the government to register the Lesbians, Gays and Bisexuals of Botswana (known as LEGABIBO), which several government ministries had denied.

In respect to trade unions, however, the government deregistered the Botswana Federation of Public Sector Unions in 2009 and acted harshly against an eight-week public sector strike involving 100,000 workers. The government summarily dismissed 2,600 health care workers and imposed a contract settlement with a minimal wage increase. The Court of Appeals upheld the government’s actions but Botswana’s High Court ordered the reinstatement of many workers. The International Labour Organization’s Committee on Labor Standards requested that the government align the law and the government’s practices with ILO standards to allow all public sector workers to organize and have the right to strike.

Minority Rights

The main minority rights issue in Botswana concerns the indigenous population, or San, numbering about 50,000 people. Since 1985, five thousand San have been removed from their homes on the Central Kalahari Game Reserve, where most lived, to other settlements having fewer services. Most other San left the Game Reserve after water resources were cut off.

The minority San community were being displaced from the Central Kalahari Game Reserve until High Court decisions guaranteed return to their ancestral homeland. A family in Grasslands. Creative Commons License. Photo by Mopane Game Safaris.

The government claimed it was too expensive to maintain the traditional hunter-gatherer culture on the San’s historic territory and that it wanted to offer greater educational and economic opportunities to the population. Critics of the government suspected it wanted to exploit diamond deposits on the Game Reserve. More than two hundred San petitioned the courts to return to their homes. In 2006, after a three-year-long court battle, the High Court ruled in their favor and ordered that those evicted be allowed to return to their ancestral lands. Another ruling in 2011 granted them access to subsurface water sources. A large number of San began to return to the Central Kalahari Game Reserve.

Concentration of Power

In 2007, President Festus Mogae created a new police agency, the Directorate of Intelligence and Security Services (DISS). It was granted power of arrest without warrants. DISS also functions without parliamentary oversight and was implicated in several suspected extrajudicial killings under Mogae’s successor, President Ian Khama. The most prominent involved members of an organized crime family. Cases also included shoot-to-kill orders of San members for poaching on the Central Kalahari Game Reserve, which is strictly regulated.

Political Opposition

In 2009, President Ian Khama suspended his main rival within the BDP, Secretary General Gomolemo Motswaledi, to prevent him from running in that year’s parliamentary elections as a BDP candidate. Motswaledi and other leaders left the BDP to form a new opposition party, the Botswana Movement for Democracy (BMD). They accused Khama of “violating the party’s constitution by concentrating power in the presidency.” The faction initially had 20 MPs from the BDP, but by the end of 2011 all but seven had returned to the BDP’s fold.

In 2012, the BMD joined with the country’s traditional opposition party, the Botswana National Front, and a third party, the Botswana Peoples Party, to form a coalition called the Umbrella for Democratic Change (UDC). Motswaledi was elected Secretary General but was killed in a car crash four months before the election. An independent investigation found no foul play was involved.

In the October 2014 elections, the ruling BDP received less than 50 percent of the national vote for the first time since 1966. It still won 37 of the 57 contested seats in the “first past the post” system, but the Umbrella for Democratic Change (UDC) won a sizable 17 seats. Its support was largely among younger and urban voters. Another center-left party, the Botswana Congress Party (BCP), won the remaining 3 seats. The UDC’s new leader, Duma Boko, a human rights lawyer, used the opposition’s new position to challenge the governing party on a number of issues, including rising corruption, abuses of power and the inequitable distribution of resources.

President Ian Khama completed his second term in April 2018. As had been the practice since independence, his vice president, Mokgweetsi Masisi, was named interim president until scheduled parliamentary elections the next year. Upon being named interim president in April 2018, Mokgweetsi Masisi acted quickly to concentrate his powers. He moved the Directorate of Intelligence and Security Services (DISS) and the Financial Intelligence Agency (see above) from their respective ministries to the president’s office. After the move, there were reports of DISS harassment of opposition parliamentarians. Masisi also fired the chief of DISS, Colonel Isaac Seabelo Kgosi in May 2019 for corruption and human rights abuses under Ian Khama’s presidency.

Current Issues

Botswana, whose independence party dominated politics since 1966, voted the Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) out of power in a surprising rebuff in 2024, This reflected a trend worldwide against incumbent ruling parties (see, for example, Current Issues in the South Africa Country Study). Events leading up to the 2024 vote are described below.

Despite rising public concerns about concentration of power, the 2019 elections saw the BDP gain 38 of the 57 seats in parliament and regain a majority national vote (52.7 percent). The opposition Umbrella for Democratic Change got 35.9 percent, less than in 2014, and fewer than one-quarter of the seats. This was an unexpected result since the other opposition party, the Botswana Congress Party, had joined the UDC coalition. The Botswana Patriotic Front (BPF), a new party led by the former president Ian Khama, who broke with the BDP, won 3 seats.

Mokgweetsi Masisi won a full term as president in 2019, as opposition to the ruling party slightly weakened in parliamentary elections. Creative Commons License. Photo by Emmanuel Berrod.

International observers deemed the elections free and fair but still reported problems with electoral procedure (a shortage of indelible ink and translucent boxes) as well as cases of voter irregularities and vote buying. The High Court dismissed the UDC’s request to invalidate the results. President Mokgweetsi Masisi, now elected to a full term, appointed a constitutional commission to address complaints of the electoral system, including review of abuse of state resources and consideration of public financing.

In January 2020, the former chief of the intelligence and security service, Colonel Kgosi, was arrested for tax evasion and in February charged with several others on suspicion of tax evasion and misuse of the National Petroleum Fund. Although there was reason to suspect corruption, the case was widely seen as politically motivated and aimed at Ian Khama loyalists. The defendants were all acquitted that December.

Fearing further defections from the BDP to Khama’s party, President Masisi had parliament pass a law that took effect in February 2021 preventing a member’s change of party during the 5-year mandate. Over his four-year term generally, Masisi failed to adequately address concerns about concentration of power or corruption and also reneged on key promises. For example, the Botswana Federation of Public, Private, and Parastatal Sector Unions repeatedly demanded that the government restore the Public Service Bargaining Council, which was disbanded in 2014. President Masisi had promised to do so in 2019 but never did. Although he reiterated his promise in April 2022, the PSBC was still not restored.

Masisi failed to adequately address concerns about concentration of power or corruption and also reneged on key promises.

As the 2024 elections approached, there was rising public discontent also with the state of the economy, which had slumped due to a worldwide decline in diamond sales. Growth went from 5 percent in 2022 to 1 percent in 2024. Unemployment rose to 28 percent, with youth unemployment at 38 percent.

Other issues affected public opinion. A bill that would have legalized same-sex relations was withdrawn in August 2023 after the Evangelical Fellowship of Botswana (EFB) lobbied against it. The bill, supported by young people, was meant to ensure compliance with a 2019 High Court ruling that ended discrimination based on sexual preference. Earlier, in 2010, the Employment Act was amended to outlaw discrimination in hiring and firing based on HIV status or sexual orientation (see also below).

In the October 30, 2024 elections, the Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) suffered a resounding defeat, winning only 4 seats and getting just 20 percent of the vote nationwide. The opposition United Democratic Congress (UDC) won 37 percent of the national vote and 38 seats, a decisive majority even in an expanded parliament of 61 voting members. The social democratic Botswana Congress Party (BCP), running separately this time, won 11 seats on 21 percent of the vote nationwide. Ian Khama’s Botswana Popular Front won 5 seats on 8 percent of the vote. Turnout was 81 percent of eligible voters (825,000 in a population of 2.5 million).

President Masisi accepted the results of the election in a quick public pronouncement. In the first peaceful transfer of power between political parties in Botswana’s history, the UDC’s leader, Duma Boko, was sworn in as president on November 1.

President Masisi accepted the results of the election in a quick public pronouncement. In the first peaceful transfer of power between political parties in Botswana’s history, the UDC’s leader, Duma Boko, was sworn in as president on November 1. In his state of the union address later that month, he pledged to renegotiate economic agreements with the De Beers mining giant regarding Botswana's diamond industry.

AIDS is a critical issue for Botswana. It has the second highest HIV-infection rate on the African continent (next only to Swaziland). By 2011, there were more than 300,000 cases (more than 10 percent of the population). However, Botswana responded to the crisis earlier and with more resources than other African countries (by contrast, see, the South Africa Country Study). Aided by the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, or PEPFAR, the government put in place education, treatment and drug programs, including early access to anti-retroviral medication. Today, 80 percent of HIV-infected persons receive anti-retroviral medication, dramatically reducing the rate of deaths due to AIDS. However, Botswana’s medical programs dedicated to fighting HIV infection have been affected by the stoppage PEPFAR funding from the United States as part of a wholesale suspension of foreign aid under the new administration of President Donald Trump.

The content on this page was last updated on .