Summary

Map of Singapore

Singapore, an island city-state located off the southern end of the Malay Peninsula, is a parliamentary republic with authoritarian governance. Freedom House consistently categorizes the country as “partly free.”

Singapore is located at the junction of the Straits of Malacca and Johur and the South China Sea. As a trading outpost for Malay and other sea-going empires beginning in 1219 CE, it became a British outpost in 1819 and a British Crown Colony in 1867. The United Kingdom granted Singapore self-governance in 1959. Singapore declared full independence in August 1965 after briefly merging with the Malaysian Federation at its independence in 1963 (see Country Study).

Since self-governance in 1959, Singapore has been ruled by the People's Action Party (PAP). Its first leader, Lee Kuan Yew, was prime minister over 31 years (1959–90) and he remained a dominant political figure until his death in 2015. His son, Lee Hsien Loong, was Singapore's third prime minister, from 2004 to 2024, when his deputy succeeded him. While there are regular elections, the government is authoritarian in practice. Courts generally restrict political parties and imprison political opponents. Singapore is also known for a restrictive culture and severe punishment of minor infractions.

Like Mahathir Mohamad when prime minister of Malaysia, Lee Kuan Yew was a defender of authoritarian “values” and argued that democracy was incompatible with Asian culture. He cited Singapore’s successful economy and stable governance as an alternative model to Western democracy.

Singapore is one of the world’s smallest states by landmass (just 693 square kms.) with the second highest population density next to Monaco. Of its 5.6 million people, 3.5 million are citizens and 2.1 million permanent residents. Seventy-four percent of citizens are ethnic Chinese, 13 percent Malay and 9 percent Indian. Religious affiliation is 31 percent Buddhist, 20 percent no religion, 19 percent Christian, 15 percent Muslim, 8 percent Taoist and 5 percent Hindu. Singapore’s economy mixes free market policies with a high degree of state direction. The International Monetary Fund ranks Singapore 31st in the world in projected nominal Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for 2024. Projected 2024 GDP per capita ranks 5th at $88,447 per annum.

History

Early History

Singapore’s earliest settlers were Chinese and Malay traders and fishermen dating from at least the early first centuries CE. Starting from 1219 CE, Singapore served as a center for trade for Malay and other sea-going empires due to its central geographic location on the Straits of Malacca and Johur between the Indian Ocean and South China Sea. Its Malay name, "Singa Pura," means "Lion City." According to legend, the name was given by a prince of the Sri Vijayan Malay Empire because he believed to see a lion on the island on his arrival. The island fell under the control of several Malay empires and in 1511 became a part of the Johor Sultanate.

British Colonization

In 1819, the British governor in India, Lord Hastings, approved a proposal of Sir Thomas Raffles, a governor of a neighboring island, to establish a new trading post in Singapore. The aim was to challenge The Netherland’s regional dominance with its colonial hold over Indonesia and Malaysia (see Country Studies).

Despite its central location and natural harbor, Singapore had been ignored by the Dutch in favor of other routes through the Strait of Malacca. Upon his arrival, Raffles signed a treaty with the Sultan of Johor granting the British East India Company trading rights in exchange for an annual fee. In 1823, the British gained full possession of the island — also in exchange for a yearly payment. On March 17, 1824, the Anglo-Dutch Treaty cemented British control over Singapore and demarcated British and Dutch holdings. The British controlled territory north of the Strait of Malacca (Singapore, Penang and Malacca) and the Dutch controlled the area to the south (Indonesia).

Sir Thomas Raffles: Founder of Modern Singapore

Sir Thomas Raffles established Singapore as a major commercial hub and set up an ethnic neighborhood structure, which survives today. After Raffles' departure in 1823, the city became one of the major ports in the world due to Malaya's rubber and tin trade together with the advent of steamships and the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 that facilitated Europe’s sea trade to and from Asia.

In 1867, the growing British merchant population lobbied for the Straits Settlements to designate the group of British-held islands around Singapore as a Crown Colony. From then, Singapore was ruled directly from London through local administration rather than by an appointed governor. Crown Colony status led to the establishment of advisory legislative and executive councils mainly of British subjects but with some non-British representation.

Japanese Occupation

In the first years of World War II, the United Kingdom suffered a series of defeats to the Japanese, including the Battle of Malaya in late 1941 and the Battle of Singapore in February 1942. The Japanese would occupy the Malaya peninsula and the Straits Settlements for more than three years. The Japanese occupation of Singapore was brutal. Up to 25,000 Singaporeans were killed. Following the Japanese surrender on August 15, 1945, British control resumed of the Maly peninsula by agreement with local representatives. The Straits Settlements was dissolved, with its main territories, Malacca and Penang, becoming part of the Malayan Union while the island of Singapore became its own Crown Colony.

From Self-Governance to Independence

The return of the UK’s milder rule was welcomed but nevertheless resented by many Singaporeans who felt that the British had failed in defense of a loyal ally against the Japanese. Singaporean leaders began to ask for greater self-rule. Facing international opposition to its continued empire, the UK government granted a plan for greater representation and self-rule.

Initial elections in 1948 were restricted to the city-state's 23,000 British subjects, who chose just six of twenty-five Legislative Council members. A Communist insurgency in Malaya led British authorities to impose a state of emergency in both colonies, but the UK was more willing to allow a Singapore-based government after elections in 1951 that included all residents were won by the business-oriented Singaporean Progressive Party.

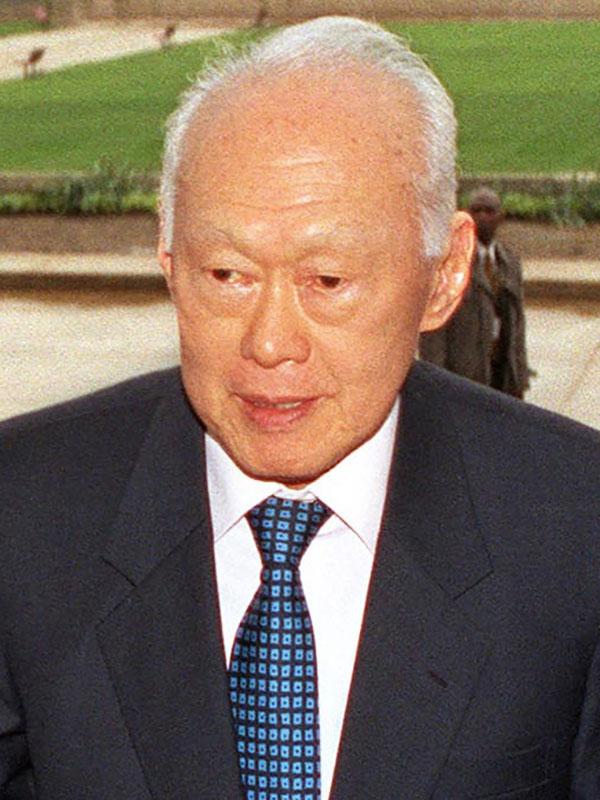

The People’s Action Party won 43 of 51 seats in the first self-governing elections in 1959 and has ruled Singapore also since declaring independence in 1965. Its leader, Lee Kwan Yew was elected prime minister in 1959 and served as such until 1990. He played a dominant role in Singapore politics until his death in 2015. Shown here in 2002 on a trip to the United States. Public Domain. Photo by Robert D. Ward.

In April 1955, elections were held for a new 32-member Legislative Assembly with twenty-five directly elected seats. Two left-wing parties, the Labor Front and the People's Action Party, won a majority. Even so, the British government approved formal self-governance for Singapore and held new elections in 1959. The People’s Action Party (PAP), which represented much of the majority Chinese community, won 43 of 51 seats for the assembly. Its leader, Lee Kuan Yew, was elected prime minister.

The main question for Singapore was its relationship with newly independent Malaysia. Voters approved a referendum to join the Federation of Malaysia in 1962 and the two merged in September 1963. But the states differed over official discrimination policy in favor of indigenous Malay as well as the constitution’s establishment of Islam as the state religion. Efforts to foment racial antipathy against ethnic Chinese in Malaya led to riots in 1964. The Malay Federation legislature expelled Singapore by a 126–0 vote (Singaporean members boycotted). Singapore declared its own independence on August 9, 1965.

The Lee Kuan Yew Model

The dominance of the People’s Action Party (PAP) in the 1959 elections was a harbinger for the city-state's future. In subsequent elections, the PAP won the large majority of seats in the parliament, now with 84 seats. PAP leader Lee Kuan Yew served as prime minister until he resigned in 1990, whereupon he continued to dominate politics, first as “senior minister” to his chosen successor, Goh Chok Tong. Lee then served as “minister mentor” to his son, Lee Hsien Loong, who was elected Singapore’s third prime minister in 2004.

Since establishing self-governance, Singapore has been highly successful economically. Both before the federation, from 1959 to 1963, and after independence in 1965, Prime Minister Lee adopted a set of policies that set Singapore on an upward economic path. These included continuing the previous legal foundations for a free-market economy established under British rule but also adopting policies of state involvement in the economy. These included direct investment in electronics production and other export sectors, the nationalization of major industries, state control of the housing development board and tax holidays to welcome foreign investment.

Rule of Law

From the outset of independence, Lee Kuan Yew ruled in an authoritarian manner. The rule of law, while uniform, was repressive. The judicial system was formally independent and structurally and procedurally based on British legal tradition, but it was controlled by the government through appointment. As a result, the courts routinely favored the ruling People’s Action Party, restricted free expression and limited opposition political activity, freedom of association and other basic rights fundamental to the rule of law.

There has not been a change of ruling party or government since 1959. Lee Kuan Yew resigned his position as prime minister voluntarily in 1990, but his successors were hand-picked by him as the dominant leader of the ruling party. Goh Chok Tong, a longtime ally as deputy prime minister, was Lee’s first successor. The next was his son, Lee Hsien Loong, whom the elder Lee had carefully groomed for power by appointing him general and head of the Finance and Trade ministries.

Lee Hien Loong was first elected prime minister by parliament in 2004 to fill the term of Goh Chok Tong, who resigned. The younger Lee continued in the post for twenty years. In 2023, he announced he would hand power to his deputy prime minister, Lawrence Wong, prior to the next elections in 2024. The elder Lee maintained a dominant influence in Singaporean politics through so-called advisory positions. Even after formally retiring in 2011, he influenced Singapore’s politics through pronouncements in the media. He died in 2015.

Opposition political parties face numerous obstacles and confront an unbalanced electoral playing field. The governing PAP’s position is bolstered by its long-time dominance over the judiciary and the media, restrictions on assembly and speech and the use of detentions through the Internal Security Act (see below). The leaders of opposition parties and the editors of opposition party newspapers have been frequently jailed or sued in court for slander. When the defamation cases are won, individuals and news outlets and other entities are bankrupted in the process.

The Reach of the Internal Security Act

While Singapore is governed by English common law, laws have often not been amended,. This has meant the maintenance of outdated provisions such as corporal punishment. For example, caning is frequent even for minor offenses such as littering or spitting on the sidewalk. As in Malaysia, a critical component of Singaporean law is the Internal Security Act, which the British imposed on all parts of Malaya and Straits Settlements in 1950 in response to a communist insurgency in Malaysia (see above). Today, this law continues to permit the Internal Security Department to take action against perceived terrorism threats or dangers to the disruption of racial and religious peace.

An Obedient Judiciary

Justices in Singapore are appointed by the president at the recommendation of the prime minister to terms lasting until the mandatory retirement at age 65, although the president may re-appoint a justice for a fixed period past retirement age. Since 1991, the president is elected by popular vote, but is effectively chosen by the ruling party, which has never lost an open election (see also Current Issues).

While some observers considered the judiciary to have achieved greater independence in recent decades, courts still regularly rule against opposition party leaders and critics of the regime both in civil slander cases and in criminal cases.

Singapore’s court system is not considered independent. It generally rules in favor of ruling party and government officials, especially when bringing defamation suits to intimidate media. Above, the new and old Supreme Court (center) in an aerial view with the backdrop of Singapore City’s skyline. Creative Commons. Photo by Zairon.

Some examples: in a precedent-setting case in 1997, Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong and other PAP members were awarded damages worth over $2 million in a slander suit brought against an opposition politician for saying in public that ruling party members were liars. In 2011, Dr. Chee Soon Juan, the leader of the Singapore Democratic Party (SDP) was barred from running for parliament after being ruled bankrupt upon failing to pay civil damages in a lawsuit ruled against him for slander. (The suit was brought by former Prime Ministers Lee Kuan Yew and Goh Chok Tong.) Dr. Chee eventually raised the $30,000 to pay the damages and was allowed to contest a seat in the 2015 elections but lost to the PAP candidate.

An Unfree Media

The media are also strongly controlled by the state. According to the 2023 Freedom in the World Survey, all domestic newspapers, radio stations, and television channels are owned by companies linked to the government. As a result, “Editorials and news coverage generally support state policies.” There is a high degree of self-censorship. An actual regime-imposed system of censorship prevents seditious or sexually related material and bans any advocacy of homosexuality. The media watchdog group Reporters Without Borders consistently ranks Singapore low in their media freedom reports. In 2023, Singapore ranked 129th out of 180 countries.

The main alternatives for independent news available to citizens are foreign print and broadcast outlets. But even these have restrictions on distributing materials with negative stories about Singapore or its political leadership. The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, Newsweek and others may be distributed only after state censorship review. (The Economist magazine refuses to be distributed under any censorship review.) Magazines deemed pornographic are banned.

In the 2006 elections, the possibility for political speech was further restricted by new rules prohibiting political commentary through websites, blogs and podcasts that might be considered biased toward a candidate or party. The clear purpose of the law was to stifle any implied criticism of the regime by supporting an opposition candidate.

A Narrow Space for Opposition

The 2011 parliamentary elections appeared to signal slight political openings. The opposition parties were able to field candidates in an unprecedented 82 of 87 contested seats. With the PAP’s overall support dropping to 60 percent of the vote, the Workers Party was able to win a record 6 seats, including one Group Representative District, where it won all 5 seats. In 2013, it added a member to parliament by winning a by-election for a vacated seat.

Presidential elections were contested for the first time starting in 1991 when the position, largely ceremonial, became directly elected. The PAP-supported candidate won in 2013 with just 35.2 percent of the vote in a narrow victory over three opponents.

The 2015 parliamentary elections, however, showed that the political space for the opposition would remain narrow. Results were nearly identical to 2011. The PAP's vote share returned to 70 percent, while the Workers Party dropped to 12.5 percent nationally. No other opposition party polled higher than the 4 percent threshold to enter parliament. Total, the PAP won 83 out of the 89 directly contested seats. The Workers Party won six seats but was allotted three more due to a 9-seat minimum representation granted opposition parties.

Supposedly to ensure ethnic representation, parliament changed the rules for the 2017 presidential election to require that only a Malay candidate could contest the seat. This knocked out the ethnic Chinese opposition candidate, Tan Cheng Bok, who narrowly lost the 2013 election. The PAP-backed Malay candidate, Halimah Yakob, won uncontested to become Singapore's first female president.

Current Issues

While the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) has a base of support, it is not possible to gauge its actual popularity given the lack of free or fair conditions for elections, the PAP’s dominance over the courts, and the pro-government influence of Singapore’s business community, whose oligarchic networks are intertwined with the ruling party.

In addition to the dominance of pro-government media and the government tilt of the judiciary, the ruling party has an enormous advantage in financial resources and infrastructure and controls the Election Department and the Election Boundaries Review Committee. These bodies adopt election rules and the boundaries of individual districts and Group Representative Constituencies where up to 5 seats are won together in party-line voting.

Lee Hsieng Loong was prepared by his father to become Singapore’s third prime minister in 2004. He stayed in the post for 20 years before handing power over to his deputy, Lawrence Wong, in May 2024. Above, Lee meets President Biden at the White House in 2022. Public Domain.

The government also determines the timing of elections. In 2015, the president agreed to Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong’s request to call elections a year early, ensuring that the opposition was unprepared. The Election Board then limited the campaign period to 9 days.

In the 2020 elections for parliament, the number of directly contested seats was expanded from 89 to 93, with a total of 14 single-member constituencies and 79 seats decided in Group Representative Constituencies (GRCs). There was reduced support for the PAP from 2015 at 61 percent, but the Workers Party and the Progress Singapore Party had just 12 percent and 10 percent, winning 10 and 2 seats respectively.

In April 2023, Lee Hsien Loong announced that he would resign in 2024 prior to the next elections and hand the reins of the PAP over to his deputy, Lawrence Wong. The transfer of power took place in May 2024.

In September 2023, a contested election (the first in a decade) was held for president. A former deputy prime minister and the PAP's candidate, Tharman Shanmugaratnam, won the election with 70.4 percent against two opponents. The next general elections for parliament are to be held no later than November 23, 2025 but may be called sooner by Lawrence Wong to gain his own electoral mandate.

The government has continued various means to restrict free expression, association and assembly to prevent the possibility for increased opposition. The Elections department, for example, banned large public rallies during the 2020 election on the basis of Covid restrictions. Also, new laws require that any internet publication, including blogs, must be approved by the Interior Ministry. In addition, the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA) now allows any government minister to order corrections and restrict access to comment considered false or against the public interest.

The opposition Workers Party has only limited possibilities to compete in elections, winning just 10 of 93 seats in parliament in 2020. Above, a Workers Party rally in 2011 in Singapore City. Creative Commons. Photo by: Abdul Rahman.

Overall, media restrictions ensure that Singaporeans do not get negative news of the government. In 2014, for example, the blogger Roy Ngerng Yi Ling was convicted of defamation for writing about mismanagement of Singapore’s retirement savings system. Another blogger, Alex Au, faced defamation suits for writing that the judiciary was biased in cases dealing with same-sex activity.

More recently, Freedom House’s 2023 Survey reports that “The last prominent independent media outlet, The Online Citizen, was forced to close in September 2021 after the Infocom Media Development Authority (IMDA), the country’s media regulator, canceled the site’s license over its alleged failure to report on funding sources.” The editor, Terry Xu, was sentenced to three weeks in jail in August 2022 on charges of defamation for publishing a letter to the editor that accused government ministers of corruption. (The letter writer was also sentenced to three months in jail for defamation.) After Xu’s release in September 2022, he relocated to Taiwan and reactivated the outlet’s website and social media accounts.

The content on this page was last updated on .