Summary

Map of Poland

Since 1989, Poland has been a free and sovereign country following more than two centuries of foreign domination or occupation, with only a brief previous period of full independence (1918-39). Today, it has a mixed presidential-parliamentary system of government.

After 1945, Poland had a communist dictatorship imposed on it by the Soviet Union, which occupied much of Central and Eastern Europe at the end of World War II. In August 1980, the birth of a mass free trade union movement, Solidarity, challenged the Polish communists’ power. Solidarity was outlawed by the communist regime in late 1981, but civic and worker resistance over 7 years ultimately forced the authorities to agree to semi-democratic elections in June 1989. The victory of Solidary led to the forming of a largely non-communist government, helping to propel the fall of Soviet communism in Central and Eastern Europe.

Since 1990, Poland has had free, fair and regular national elections. There are regular transfers of power among political parties at both national and local levels. A new constitution formalizing a presidential-parliamentary system of government was ratified by referendum in 1997. Poland joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 1999 and the European Union (EU) in 2004.

Parliamentary elections in 2015 brought the national conservative party, Law and Justice (PiS), to power. Its adoption of party-directed judicial reforms and control of state media, among other policies, put Poland in conflict with the EU over adherence to democratic standards. In Freedom House’s annual Survey of Freedom, Poland was considered a “backsliding democracy,” dropping 10 points in overall rating (90 to 80 on its scale of 100), but remained in the Free category. In October 2023, a coalition of center-right and center-left parties won a majority of seats in parliamentary elections in a high-turnout election. While Law and Justice was ousted from power, the new government has difficulty in reversing PiS’s takeover of the judiciary and other institutions.

Poland is the 69th largest country in the world and Europe’s 9th largest by area (312,685 square kilometers). It has a population of around 39 million people. The International Monetary Fund ranked Poland 21st in the world in projected 2024 nominal Gross Domestic Product ($844 billion) and 50th in projected nominal GDP per capita ($23,014 per annum).

History

Poland's statehood dates to 966 CE from Mieszko I's conversion to Christianity and the establishment of the Piast dynasty (966–1370), which was succeeded by the Jagiellonian dynasty (1386-1572). In the 13th and 14th centuries, Polish kings mandated that there would be religious freedom on Polish territory, which made it a place of refuge for Jews being persecuted and expelled from other European kingdoms.

A map of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth showing the borders from 1635-1686. Creative Commons License. Original map by Krzysztof Machocki. Modifications by Hoodinski.

The establishment of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1569 ended Poland's dynastic monarchy with the death of the last Jagiellonian king three years later. Adopting what were called the Henrician Articles, the Commonwealth accorded semi-democratic powers to the Sejm, or parliament, and included election of the Polish king on the principle of non-hereditary succession — rare in Europe at the time. The Sejm also held powers to approve or itself levy taxes. In 1573 it passed an act formalizing the kingdom’s prior guarantee of religious freedom.

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth weakened due to the adoption of the liberum veto, by which a single member of the Sejm could exercise a veto on its actions. The rulers of Prussia, Austria and Russia took advantage of the practice to gain influence over the Commonwealth through bribes. Failed alliances and wars aimed at protecting the Commonwealth led in 1772 to the Kingdom of Poland’s first loss of territories and partition by the three empires.

The Sejm’s adoption of the May 1 Constitution in 1791, inspired by the American and French Revolutions, established a short-lived republic and period of liberal constitutionalism in Poland’s remaining territory.

The Sejm’s adoption of the May 1 Constitution in 1791, inspired by the American and French Revolutions, established a short-lived republic and period of liberal constitutionalism in Poland’s remaining territory. A year later, following an uprising led by Tadeusz Kosciuszko (who had participated in the US revolutionary war), Russia invaded and ended the Commonwealth altogether. In a second partition in 1793, and then finally a third one in 1795, Russia, Austria and Prussia placed Poland and Lithuania fully under foreign subjugation. For more than a century, Poles organized underground universities, political parties and several uprisings, especially against Russian domination. Despite such resistance, the Poles were unable to break free of foreign control until the fall of the empires of the three partitioning powers at the end of World War I.

Independence & the Second Polish Republic

In the aftermath of World War I and the 1917 Russian Revolution, Poland regained its independence. The Second Republic was established in 1918. Under the military leadership of Marshal Józef Pilsudski, the new independent state repelled the invasion of the Bolshevik Red Army in 1919–20.

In the aftermath of World War I and the 1917 Russian Revolution, Poland regained its independence. The Second Republic was established in 1918.

Poland's society and politics experienced a rebirth. Conservative, liberal, socialist and ethnic parties competed for influence in the Sejm and the upper house of parliament, the Senate. Marshal Pilsudski, however, assumed greater powers as military leader in an effective coup in 1926 overthrowing the elected president. Becoming more authoritarian over time, Pilsudski used an army-backed political movement, state propaganda, intimidation and arrests to assert greater dominance. There continued to be political competition and Pilsudski oversaw policies generally protective of minorities, but the last relatively free election within the Second Republic was in 1928.

After Pilsudski’s death in 1935, the army-backed Sanation movement asserted its leadership under a new president and constitution. As in other countries in the 1930s, far-right anti-Semitic political forces gained greater prominence and Poland’s Jewish minority felt increasingly threatened.

War and Cataclysm

Independence ended in September 1939 when German and Soviet forces occupied western and eastern parts of the country. The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, signed on August 23, had established an alliance between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union allowing Adolf Hitler to launch the Second World War. Under secret protocols, the two powers divided all of Eastern Europe between them, with the Soviet Union occupying eastern Poland, the Baltic Countries, Moldova and other territories. The dual occupations were a cataclysm, turning Poland into one of the “bloodlands” of World War II.

Independence ended in September 1939 when German and Soviet forces occupied western and eastern parts of the country. The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, signed on August 23, had established an alliance between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union allowing Adolf Hitler to launch the Second World War.

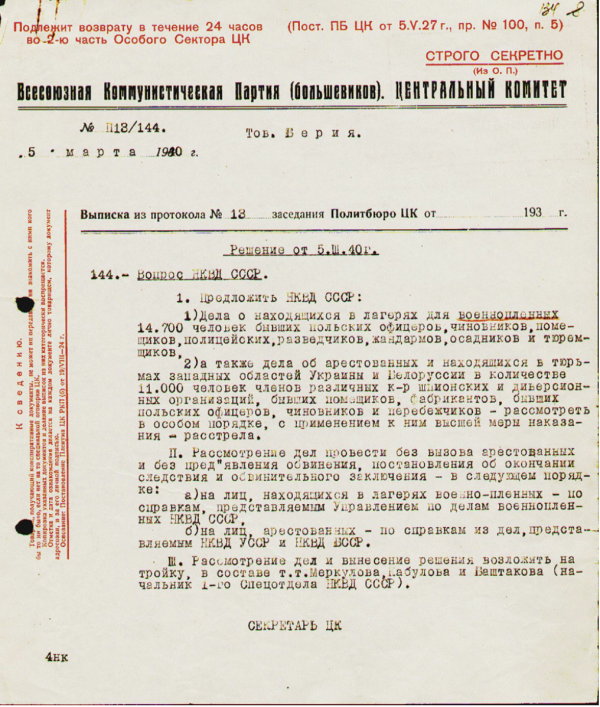

During its occupation, the Soviet Union imprisoned or forcibly sent hundreds of thousands to camps in Siberia and Central Asia. One of the war’s worst atrocities was the Katyn massacre of 22,000 Polish officers, politicians, intellectuals and religious officials. When mass graves were discovered, the Soviet Union blamed the massacre on the Nazis, however physical evidence later proved that the executions were conducted by the Soviet secret police.

In his quest for lebensraum (“living space”) and full dominance over Europe, Hitler broke his pact with Soviet leader Joseph Stalin in June 1941. The Wehrmacht invaded the USSR and also occupied Eastern European countries that the Soviet Union had seized.

Polish and Jewish resistance movements could not stem Germany’s violent occupation and genocidal policies. An estimated six million Polish citizens were killed from 1939 to 1945, mostly under German occupation. Of those, three million Polish Jews were murdered in the Holocaust (or Shoah), the Nazi regime’s systematic campaign to exterminate all of European Jewry (see also Germany Country Study).

Six million people were killed in Poland during the German and Soviet occupations during World War II, including three million Polish Jews in the Holocaust. Photo: The “Gate of Death” leading to the gas chambers at Auschwitz-Birkenau. Creative Commons License: Photo by Michal Zacharz.

The Communist Period

Under Soviet direction, the governments in all the “people’s republics” carried out a terror campaign of show trials, executions and repression that eliminated political opposition and independent organizations.

The Soviet Union, now joined with the wartime Allies and supplied militarily by the U.S.’s Lend-Lease Program, repelled the Wehrmacht’s invasion after heavy fighting. In 1944, the Red Army advanced to occupy most of Central and Eastern Europe, including Poland. However, instead of engaging Nazi forces in the approach to Warsaw, the Red Army waited on the banks of the Vistula River and allowed the Wehrmacht to destroy Poland’s non-communist resistance army as well as much of the capital city during the Warsaw Uprising. A Soviet-created government was established in Lublin despite a government-in-exile having been maintained since 1939 and recognized by the United Kingdom and the United States.

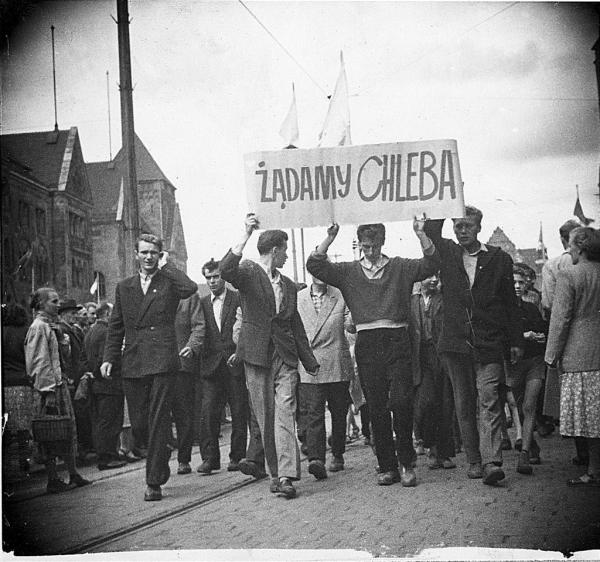

Workers protested communist rule in a series of uprisings. In 1956, in Poznan, tanks and soldiers suppressed the “Freedom and Bread” protests, killing at least 57 people. The poster reads: “We Demand Bread.” Public Domain.

The February 1945 Yalta Agreement, signed by the Allied leaders of the USSR, the UK and the U.S., effectively ceded Poland and other countries of Eastern Europe to the Soviet Union’s control. Soviet pledges to ensure free elections in the occupied countries were broken. Manipulated elections were carried out under conditions of police violence and intimidation that ensured pro-Soviet national communist party takeovers of all Eastern European governments. So-called “people’s republics” were established.

Under Soviet direction, the governments in all the “people’s republics” carried out a terror campaign of show trials, executions and repression that eliminated political opposition and independent organizations. All liberal influences within society were officially purged. Books were banned. Trade unions were taken over by the communist party and made into instruments to control the workforce. In Poland, due to a defiant stand by its Archbishop, Cardinal Stefan Wysziński, Poland’s Catholic Church retained independence and legal autonomy, alone among religious structures in the Soviet-bloc countries.

Polish Resistance and the Solidarity Movement

Despite the country’s traumatic wartime experiences, Polish society organized resistance to communism in the spirit of its national independence movement. . . . In August 1980, a strike at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdansk propelled a nationwide strike movement.

Despite the country’s traumatic wartime experiences, Polish society organized resistance to communism in the spirit of its national independence movement of the 18th and 19th centuries. There were revolts and protests by workers and students in 1956, 1968, 1970 and 1976, each of which were suppressed by Polish military and police. In response to student protests in 1968, the communist regime undertook a vicious anti-Semitic campaign as part of its repression, prompting many of Poland’s remaining Jews to leave the country.

In August 1980, a strike at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdansk propelled a nationwide strike movement. The workers forced the Polish authorities into negotiations, leading to the signing of the Gdansk Accords. Among other gains, the accords granted workers and state employees the right to form free trade unions independent of communist state or party control. Within one month, ten million workers had joined the Independent and Self-Governing Trade Union, Solidarity, challenging the communist state’s claim to be a “workers’ state.”

Martial Law & Solidarity’s Underground Resistance

Sixteen months later, the government, under the leadership of General Wojciech Jaruzelski, imposed martial law (in Polish a “state of war”). Thousands of union activists were arrested, including Solidarity’s leader Lech Walesa. Strikes and demonstrations were brutally suppressed. Independent unions, associations, publications and assemblies were prohibited.

The Polish communist regime declared martial law in December 1981 to crush the Solidarity movement. Tanks in Warsaw on December 13, the day martial law was imposed. Photo by J. Żołnierkiewicz.

The Solidarity union re-organized itself underground, or clandestinely. After seven years as an underground resistance movement, Solidarity union structures carried out a nationwide strike in 1988. Under increasing social and economic pressure, General Jaruzelski agreed to negotiations between the government and opposition representatives. A Roundtable Agreement the next year relegalized Solidarity and allowed semi-free elections in June 1989. As described in the section below, these events, along with the Soviet Union’s weakening hold on Eastern Europe, set Poland on the course toward democratization and the holding of free elections.

Free, Fair and Regular Elections

Poland prior to 1989 had little history of free and fair elections. During the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, a Sejm (or parliament) was elected based on limited suffrage of landed elites. When under a first, partial partition by Prussia, Austro-Hungary and Russia, the “Great Sejm” of 1788-92 acted to try to preserve Poland’s remaining territories. Elected with somewhat expanded suffrage, the Great Sejm adopted the May 3 Constitution in 1791 to establish Poland's First Republic. Russia responded by invading the next year and under a second and then third partition imposed in 1793 and 1795, all of Poland was divided among the three empires for the next 123 years.

Poland regained independence in 1918 after the First World War ended. There were two free elections in Poland’s Second Republic (1919 and 1922) with up to 12 political and ethnic parties represented in the Sejm. Following a 1926 coup by General Józef Pilsudski, elections were held under less free conditions and the parliament’s powers were more limited. The Nazi and Soviet invasions of Poland in September 1939 ended this period of independence.

The rise of the Solidarity free trade union movement in 1980 challenged the communists’ power and the regime imposed martial law. The union’s sustained resistance ultimately forced the regime into negotiations in 1988.

After World War 2, the Soviet Union imposed a communist regime in Poland under forced occupation and with changed borders that moved its national territory westward. Manipulated elections in 1947 brought national communist and satellite parties fully to power. The People’s Republic of Poland was established in 1952 under a new constitution. Thereafter, elections were controlled and no opposition parties allowed.

The rise of the Solidarity free trade union movement in 1980 challenged the communists’ power and the regime imposed martial law. The union’s sustained resistance ultimately forced the regime into negotiations in 1988. An agreement allowed semi-free elections on June 4, 1989 that led to a rebirth of Poland’s independence and democracy. Since then, there have been free, fair and regular parliamentary and presidential elections under a Third Polish Republic but with recent concern of democratic “backsliding.” Poland’s rebirth of democracy is described below.

The Crooked Path to Democracy

The communist regime’s imposition of martial law in December 1981 aimed to suppress the Solidarity movement. Outlawed, the union went into a period of sustained underground resistance that kept Solidarity structures and members active, albeit under constant pressure by police. After seven years, in the summer of 1988, Polish workers launched national strike actions lasting one month. The regime, under increasing social, economic as well as international pressure, was again forced to negotiate with the Solidarity opposition.

Solidarity’s resistance over 7 years forced the government to agree to semi-free elections on June 4, 1989. The citizenry’s decisive support for Solidarity led to the end of the communist regime. Above, a rally for Solidarity candidates in Gdansk. Photo by Janusz Rydzewski.

A Roundtable Agreement was reached in the spring of 1989 in which the government agreed to quasi-democratic elections to be held on June 4, 1989. These opened one-third of the Sejm's seats to real competition, as well as all 100 seats in a recreated, but largely powerless, Senate. The government, however, still intended to retain communist control over the state. Two-thirds of the Sejm’s seats were reserved for the communist party and its satellites. Although relegalized, Solidarity was not allowed to put forward candidates. Independent candidates ran for open seats under the umbrella “Citizen Committees of Lech Walesa,” who was still Solidarity’s leader.

The campaign for the June 1989 elections took place in an atmosphere of relative freedom. . . . The enormity of Solidarity’s electoral victory and the communists’ defeat led to the desertion of satellite parties and the undoing of the regime.

The campaign for the June 1989 elections took place in an atmosphere of relative freedom. Citizens seized the opportunity to make more radical change. They cast their votes overwhelmingly for Solidarity-affiliated candidates but refused to mark ballots for communist candidates. Solidarity-affiliated candidates won all but one contested seat in the Senate. Meanwhile, no communist party candidates reached a required 50 percent threshold of votes cast. A contrived (and extra-legal) second round of voting had to be held without a threshold. In the end, the enormity of Solidarity’s electoral victory and the communists’ defeat led to the desertion of satellite parties and the undoing of the regime.

Three months later, in September 1989, the first largely non-communist government in the post-war Soviet bloc was established by Solidarity representatives, although the presidency and ministries of defense and internal affairs were retained by communist leaders for another year. Amidst the crises then unfolding in the Soviet Union, Polish events set in motion other mass protest movements that led to the rapid fall of communist regimes throughout Central and Eastern Europe by the end of 1989.

The Third Republic: New Constitutions

Although still governed under the constitution of the Polish People’s Republic, the period after 1989 is known as the Third Republic.

Amendments to the constitution passed by the new Sejm led to the first free presidential election in December 1990 and the first fully free parliamentary elections in 1991 (see also below). In 1992, the Constitution was amended further to formalize a mixed parliamentary-presidential system, enhance the powers of the Senate and institutionalize free-market reforms. Still, many institutions of the communist regime remained, which delayed the country’s political transition.

A new constitution adopted by public referendum in May 1997 laid more solid foundation for the Third Republic. It re-affirmed the mixed presidential system in place and adopted more fully democratic standards required by the Council of Europe, NATO & EU.

A new constitution adopted by public referendum in May 1997 laid more solid foundation for the Third Republic. It re-affirmed the mixed presidential-parliamentary system in place and adopted more fully democratic standards required by the Council of Europe, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the European Union (EU). The president, who is the head of state and commander of the armed forces, is directly elected every five years and may not serve more than two terms. The prime minister, who is the head of government, is chosen by the majority party or coalition in the Sejm (the lower house of parliament). A Constitutional Court, whose members are appointed by the president and approved by the Sejm, determines the constitutionality of laws and a Supreme Court oversees the judiciary. The Senate gained enhanced powers to veto legislation and oversee foreign policy.

Free and Regular Elections

Since 1989, there have been seven presidential elections and ten parliamentary elections, with numerous transfers of power between parties and coalitions. . . . All have been considered generally free and fair by international standards.

Since 1989, there have been seven presidential elections and ten parliamentary elections, with numerous transfers of power between parties and coalitions. Local elections are also regular. All have been considered generally free and fair by international standards, although more recent elections have been questioned for unfair conditions (see Current Issues).

In December 1990, a fully free election resulted in Solidarity leader Lech Walesa becoming the first non-communist president since the onset of World War II. The first free parliamentary elections were held in 1991. Because no formal Solidarity political structure arose, there was a fracturing of political parties. Twenty-eight parties gained seats in the Sejm and Senate. The largest, with 12 percent of the vote, was associated with the Solidarity movement. It formed a coalition government with two other non-communist parties. The second largest party was the reformed communist party, the Democratic Left Alliance (SLD).

In December 1990, a fully free election resulted in Solidarity leader Lech Walesa becoming the first non-communist president since the onset of World War II. The first free parliamentary elections were held in 1991.

Thereafter, with the aim of achieving a less fragmented parliamentary system, a 5 percent threshold for parties (8 percent for coalitions) was established for the Sejm. The d'Hondt method, a standard European model favoring larger parties, was adopted for allocating seats and redistributing votes of parties not meeting the 5 percent threshold. The Senate, the second house of parliament, continued to be selected by direct election in district constituencies in a “first past the post” round of voting.

Alternations in Power

The next three parliamentary elections resulted in the alternation of governments coalitions between a Solidarity-affiliated coalition (1992–93 and 1997–2000) and the post-communist SLD (1993–97 and 2001–05).

In 1995, Alexander Kwasniewski, the leader of the SLD, defeated Lech Walesa in his bid for re-election as president (52 to 48 percent). This established full control by former communists over the government just six years after their ouster in 1989. But when a Solidarity electoral alliance took power in parliamentary elections in 1997, Kwasniewski adopted a more pro-Western and pro-European stance in accord with the Solidarity Electoral Action. He presided over Poland’s joining of NATO in 1999 and, after re-election in 2000, the joining of the European Union in 2004.

There continued to be alternations of power. Parliamentary elections in September 2005 brought about the decisive defeat of the SLD, which was perceived to protect the privileges of the former communist elite. The party never recovered and later gained seats in parliament only as part of coalitions.

Two new right-oriented, post-Solidarity parties emerged to dominate politics. The Law and Justice party (PiS) mixed national conservativism and statist economic policies. The second, Civic Platform (PO), was a classic liberal and pro-EU party. The two could not form a coalition. PiS formed two minority governments with smaller parties as a result.

Lacking stability, the government lost a no confidence vote in 2007. New elections gave PO a decisive victory with 41.5 percent of the vote and enough seats to form a stable coalition. Based on strong economic growth policies, Civic Platform won a large plurality again in the regular 2011 elections. It was the first time since 1989 that a political party had won successive elections.

Presidential Elections and Tragedy

A copy of Protocol 13 of a 1940 Politburo meeting ordering the Katyn Massacre of at least 23,000 Polish officers and others by NKVD troops, among the worst atrocities of World War II. The Soviet Union denied responsibility for the crime until 1990.

In presidential elections in 2005, Law and Justice’s leader, Lech Kaczynski, had defeated the Civic Platform’s Donald Tusk in 2005 by a 54 to 46 percent margin. Near the end of his term, on April 10, 2010, Kaczynski, along with 95 leading Polish government officials, died in a tragic airplane accident near Smolensk, Russia in bad weather conditions. The large delegation was traveling to attend a joint Polish-Russian ceremony to honor the victims of the Katyn massacre following a formal admission for the first time by the Russian government of the Soviet Union’s responsibility for the massacre (see History section above). Polish-Russian relations deteriorated as the Russian government rejected any Polish government participation in its official investigation. The final report placed sole blame for the plane crash on the Polish pilots and passengers and exonerated the Russian air traffic controllers who had approved the bad-weather landing.

Under the constitution, the speaker of parliament, Civic Platform’s Bronislaw Komorowski, assumed the presidency after Kaczynski's death until new elections. In June 2010, he defeated PiS’s candidate, Lech’s twin brother and political partner, Jaroslaw Kaczynski.

A Change in Course

In 2015, an untested Law and Order (PiS) candidate, Andrzej Duda, won the presidency in a close second-round run-off with Komorowski (52 to 48 percent). This signaled a wider disenchantment with the Civic Platform (PO) due to corruption scandals and neoliberal policies. In parliamentary elections, PiS won a large plurality of 42 percent to PO’s 26 percent. Under the D’hondt method for re-allocating seats, the dominant margin gave PiS the first full governing majority of seats in the Sejm since 1989. It also won a majority in the Senate, elected in a "first-past-the-past system" for district-level seats.

Largely based on support for less austere economic policies and its public subsidies for families, PiS repeated its parliamentary victory in 2019 elections, although losing its majority in the Senate. Andrzej Duda repeated his victory in 2020 presidential elections, but by a closer margin (51-49 percent), against the opposition candidate, the Mayor of Warsaw. Both elections’ fairness was questioned by international observers, especially due to government control over state television that skewed election coverage in PiS's favor.

Under its dominant governance from 2015 to 2023, PiS sought to establish control over the judiciary, the media and other institutions in a manner reflecting "backsliding" democracies. In the most recent election, PiS lost power to a broad alliance of center-right to center-left parties. This recent period is described below.

Current Issues

The presidential and parliamentary elections of 2015 brought a marked change in Poland’s politics. Having established itself as the dominant political party, Law and Justice (PiS) moved the country’s politics away from economic and social liberalism to national and religious conservatism.

The presidential and parliamentary elections of 2015 brought a marked change in Poland’s politics. Having established itself as the dominant political party, Law and Justice (PiS) moved the country’s politics away from economic and social liberalism to national and religious conservatism. In doing so, it set out to dominate the judiciary, media, civic space and economy. It also adopted harsh anti-migrant, anti-abortion and anti-LGBTQ policies reflecting a clear illiberal direction in governance. As a result, Poland was listed among Freedom House’s “backsliding” democracies, with a 10-point drop in its rating since 2016. In elections in October 2023, however, a center-right to center-left coalition won a clear parliamentary majority in another decisive shift by Polish voters, this time away from an increasingly authoritarian turn.

In its eight years in power, PiS had also adopted a number of policies popular with the public, including state subsidies for families, reducing the retirement age to its previous level and rejecting the EU’s plan for receiving migrants from Africa and Asia. Its less popular policies, however, such as a ban on abortion and actions aimed at establishing greater political control over the judiciary, led to mass protest demonstrations.

The PiS takeover of the judiciary was fairly complete. President Duda’s judicial appointments established party dominance over the Constitutional Court, which then approved new laws on the judiciary that gave government officials control over both appointments and disciplinary action of judges. PiS also took over state television and other broadcast media and made them an instrument of party propaganda. Officials took regulatory and other action favoring politically aligned media and established a pattern of government intimidation of private media by bringing numerous libel suits.

PiS’s anti-liberal policies, including government support for local adoption of “LGBT free zones,” put Poland in conflict with the European Union over basic democratic principles and governing practices.

PiS’s anti-liberal policies, including government support for local adoption of “LGBT free zones,” put Poland in conflict with the European Union over basic democratic principles and governing practices. The EU brought a total of 41 infringement cases charging Poland, the largest recipient of EU funds, with violating EU rules. While many were over economic subsidy policies benefitting PiS supporters, the most significant breach with the EU was over PiS’s takeover of state media and the judiciary. The European Court for Human Rights ruled that the latter violated Poland’s commitments to EU rule of law requirements, including provisions in the European Convention on Human Rights, and was thus anti-constitutional.

Until 2022, Poland’s PiS government formed an alliance with Hungary’s government, led by Prime Minister Viktor Orban. His party, Fidesz, had come to power in 2010 with a supermajority in parliament having an anti-liberal platform. The Fidesz-dominated parliament adopted a new constitution and other laws designed to entrench Orban and his party in power by establishing their control over the electoral process, the judiciary, media, education and the economy. Within the EU, PiS joined Fidesz in objecting to claimed encroachments on national sovereignty in areas of migration, women’s rights, LGBTQ+ rights and other social rights protected under the European Convention on Human Rights. In contrast to Hungary, however, the Polish government made greater attempts to negotiate with the EU over its objections to Poland’s laws and practices.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 ended the PiS-Fidesz alliance. Viktor Orban, having also adopted favorable ties with Russia, acted to prevent stronger EU sanctions, withheld direct support for Ukraine and maintained Hungary’s oil and gas imports from Russia. On the other hand, Poland’s political parties unified behind the PiS government’s strong support of Ukraine and against Russian aggression. Poland’s civil society also re-found some of its strength from the Solidarity period in organizing support for more than 2.5 million Ukrainian refugees at the outset of the war (1 million refugees remained as of mid-2024).

Poland has had free elections since 1989 although international observers have raised questions about fair conditions in recent elections. Shown here is a rally for the opposition candidate during the 2020 Polish presidential election. Creative Commons License. Photo by Silar.

As the 2023 elections approached and dissatisfaction with PiS’s government increased, the national unity in foreign policy fractured. PiS leaders attacked the head of the opposition Civic Platform, Donald Tusk, as a “German agent” and state media promoted conspiracy theories around “enemy” collaboration with both Germany and Russia. PiS also pushed through a law targeting opposition leaders with supposed “Russian influence” — seemingly directed at Donald Tusk. This flagrant targeting of political opposition prompted the largest demonstration in Poland since 1989 estimated at 1 million people.

On October 15, Poland held its tenth free parliamentary election since 1989. After eight years of PiS dominance and increasingly authoritarian and anti-liberal policies, various international assessments were that the conditions were no longer fully fair, especially given government control of state media and its propagandistic character. However, most conditions remained fair and there was a much higher participation of voters (74 percent as opposed to 62 percent in 2019) due to large civic turnout efforts, especially among youth.

In elections in October 2023, a center-right to center-left coalition won a clear parliamentary majority in another decisive shift by Polish voters, this time away from an increasingly authoritarian turn.

Voters took another decisive turn, this time in support of three center-right and center-left parties that joined in an anti-PiS coalition. Law and Justice still won a plurality of 35 percent but it dropped eight points from 2019 despite running in coalition with other right-wing parties. The three anti-PiS parties won a total of 54 percent and a clear majority in the Sejm as well as the Senate.

President Andrzej Duda, however, asked PiS to form a new government, delaying the process by two months and allowing PiS to consolidate its hold on government offices. Finally, Donald Tusk, the leader of Civic Coalition (an alliance of center parties led by Civic Platform), was elected prime minister by a parliamentary vote of 248 to 201. (Civic Coalition had come in a close second in the election at 31 percent.) A new coalition government — made up of Civic Coalition, the Polish People’s Party, Poland 2050, Third Way and the Left — was approved and took office on December 13. Since assuming power, Prime Minister Donald Tusk and the new government have confronted the difficulty in changing PiS’s policies and hold on governing institutions. The Constitutional Court is still controlled by PiS appointees and the incumbent PiS-aligned president holds a veto over much legislation.

Thirty-five years since the fall of Soviet-imposed communist rule in 1989, Poland . . . holds regular, free and (mostly) fair elections in which there is genuine political competition. There has developed a vibrant civil society and private media.

As a result, Prime Minister Tusk has used unusual means to try to achieve change. For example, the parliament passed a law overriding a Constitutional Court order that ruled against the government’s dismissal of the news staff of the state television station. The move put an end to continued propagandistic broadcasting in favor of PiS. The government confronts similar difficulty in changing the Constitutional Court, the Supreme Court and other parts of the judiciary, as well as institutions that have appointed positions with long-lasting mandates and thus not removable with a change of government. The new government’s actions have raised the dilemma of using non-constitutional methods to achieve democratic reform (see articles in The New York Times in Resources).

European Parliament elections in early June 2024 showed that voter sentiment had not changed significantly since the new government took office. The Civic Coalition received 37 percent, PiS 36 percent, the far-right Confederation 12 percent and two of the other government partners, Third Way and The Left, received 13 percent total.

• • •

Thirty-five years since the fall of Soviet-imposed communist rule in 1989, Poland is at a crossroads in its democratic transition. On the one hand, the country holds regular, free and (mostly) fair elections in which there is genuine political competition. There has developed a vibrant civil society and private media. Several constitutional checks and balances proved important after Law and Justice lost its majority in the Senate in 2019 elections. Poland is anchored in Europe and the West as a member of the EU and NATO and it has emerged as a strong voice within those bodies in defense of Ukraine against Russian invasion. At the same time, the national conservative Law and Justice party’s governance during its eight years in power came under strict scrutiny by the European Union, the European Court for Human Rights and other human rights bodies due to the weakening of democratic institutions and practices. While a new government came to power in the most recent elections, many of PiS’s actions entrenched party control over many institutions, especially the judiciary. A return to democratic practices is proving problematic.

The content on this page was last updated on .