Summary

The Socialist Republic of Vietnam is a unitary republic and one-party dictatorship. Since North Vietnam’s forcible takeover of South Vietnam in 1975, Freedom in the World has categorized the united country as “not free.”

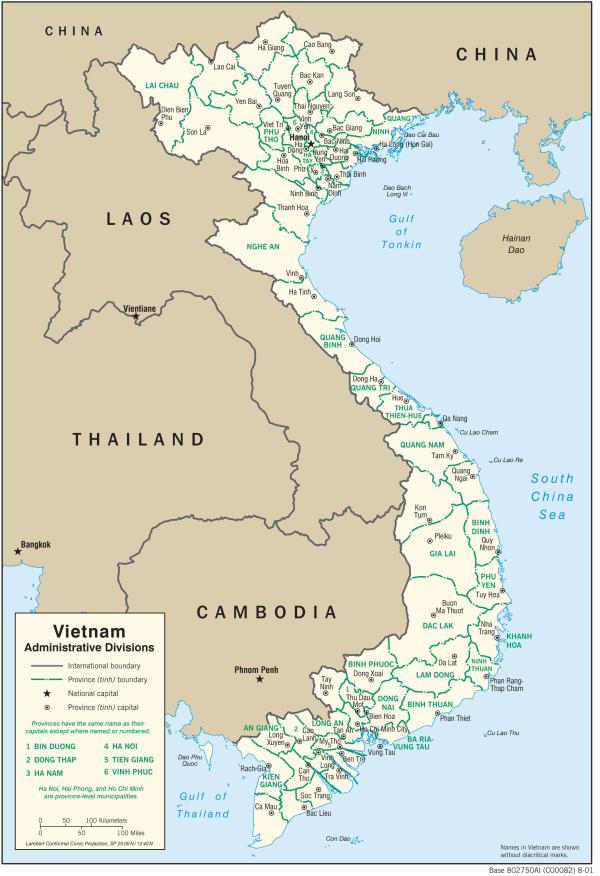

Map of Vietnam

Vietnam’s early civilizations date to the first and second millennia BCE. Chinese imperial rule started in 208 BCE, was entrenched in 111 BCE, and only expelled in the 10th century CE. Resistance of Vietnamese dynasties to further domination fostered a strong sense of nationalism. France colonized Indochina in the second half of the 19th century but withdrew in the mid-20th century after severe losses in an anti-colonial guerilla war.

The 1954 Treaty of Geneva established two separate countries, South and North Vietnam. The civil war that followed, in which the United States sided with the non-communist south, ended with the unification of the country by force by the communist north, which had support of the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China. Severe repression of the south by the north caused one of the worst refugee crises of the post-war period.

The unified Socialist Republic of Vietnam is modeled on the Soviet Union and People's Republic of China. It is a one-party dictatorship with an oppressive police-state apparatus, controlled media and limitations on human rights, including freedom of religion, expression and association.

The Socialist Republic of Vietnam is a unitary republic and one-party dictatorship. Since North Vietnam’s forcible takeover of South Vietnam in 1975, Freedom in the World has categorized the united country as “not free.”

There was a wide range of belief systems in Vietnam (Buddhist, Confucianist, Taoist, Catholic and Protestant) but few periods of religious freedom. South Vietnam had some religious freedom, but religious groups opposed to the government were repressed. North Vietnam and the unified Socialist Republic established full state control over religion.

Vietnam adopted reforms in 1986 to allow foreign investment and aspects of a free market, but the economy remains mostly state controlled. According to the International Monetary Fund, nominal Gross Domestic Product (GDP) grew to a projected $465 billion in 2024 (ranked 33rd in the world). With a population of nearly 100 million people (ranked 16th largest), nominal GDP per capita remains low at $4,623 per year (120th in the world).

History

Early Habitation and the Chinese Millennium

The earliest record of human habitation in Indochina (comprising Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos) dates to 46,000 years ago. Vietnam’s early civilization dates to the second millennium BCE. Vietnamese, ethnically and linguistically related to Southeast Asians, were strongly influenced by interaction with Han Chinese to the north. In 208 BCE, a Chinese general conquered a Việt kingdom in the Red River Delta region. A larger area was taken over by China's Han dynasty in 111 BCE, which began a millennium of formal Chinese imperial rule.

In this period, Chinese administrators imposed a Confucian system of law and religion and also developed roads, ports and irrigation. Governors cooperated with local ruling elites to establish an agricultural maritime trade, opening the region to Indian influence and the spread of Buddhism.

Vietnamese Dynasties and Rebellions

After several unsuccessful rebellions, a local Vietnamese general expelled the Chinese rulers in 939 CE and established an independent state. Two early dynasties were short-lived and succeeded by the Lý dynasty, begun by another general, which lasted from 1009 to 1225 CE.

The Lê Lợi dynasty (1407-1788), the longest-lasting of Vietnamese ruling periods, was begun by a court-scholar who led a rebellion in the early 15th century against re-imposition of Chinese rule. Above a statue of Lê Lợi in Thang Hoa province. Creative Commons. Photo by: Nguyễn Thanh Quang.

The country, then named Đại Việt, established Buddhism as the state religion. Đại Việt expanded southward along the coastal plain, a process that continued under a succeeding dynasty, which also fended off Mongol invasion attempts from the north in the 13th century. In 1407, the Chinese Ming dynasty was invited to quell a peasant rebellion, but a court scholar named Lê Lợi led another rebellion to reclaim Vietnam’s sovereignty.

Lê Lợi established a new Vietnamese dynasty lasting until 1788 (the longest in the country’s history). By the 16th century, however, the country was effectively divided by two warlord families, the Nguyễn family in the south and the Trinh in the north. Both pledged allegiance to Lê rulers, but engaged in prolonged battles for control of territory.

In 1771, peasants rose up in a rebellion to end the warlords’ high taxation for war. Led by three brothers and lasting thirty years, the Tay Son rebellion ended in defeat for both the Nguyễn and Trinh warlords. The three brothers divided the country into three provinces and each largely redistributed land and wealth. But famine and disorder weakened their rule. A French-backed military force led by a surviving general of the Nguyễn warlord family seized control in 1802.

The Last Dynasty to French Protectorate

The general, Gia Long, moved his imperial capital from Hanoi to Hue, renamed the country to its present name, Việt Nam, and created a new dynasty named for the Nguyễn warlord family. Gia Long reestablished the privileges of major landowners and re-imposed onerous taxes, forced labor and obligatory military service on peasants. Rigid neo-Confucianism and other aspects of the Chinese state system were adopted, while Buddhism, Taoism and folk religions were diminished.

Emperor Napoleon III ordered an invasion in 1857. By 1862, Tự Đức, the last ruler in the Nguyễn dynasty, ceded the south region.

The government also cracked down on growing numbers of Roman Catholics converted by French missionaries. While the French government had backed Gia Long's rise to power, he considered French and Catholic influence a threat to his regime. The authorities began executing and expelling local missionaries, who appealed to France’s ruler, Emperor Napoleon III, for help. Emperor Napoleon III ordered an invasion in 1857. By 1862, Tự Đức, the last ruler in the Nguyễn dynasty, ceded the south region. By 1883, French protectorates extended to the northern and central parts of Vietnam and to neighboring Cambodia. The four territories were organized as the Indochinese Union in 1887. Laos was added in 1893.

French Colonial Rule and Resistance

Many Vietnamese, particularly the persecuted Catholic community, accepted French control in comparison to repressive Nguyễn emperors. The policies of French governors, however, were also oppressive and alienated the Vietnamese population. French administrators replaced the existing bureaucracy of Confucian scholar-officials. French settlers, known as colons, took over concentrated landholdings, displacing Vietnamese peasants and instituting exploitative labor practices.

In 1925, Hồ Chi Minh, educated in Paris, joined colleagues to create the Revolutionary Youth League, which formed the basis for the Indochinese Communist Party (ICP).

Armed resistance groups emerged to restore the precolonial system but these soon adopted European-inspired liberal and communist ideas. Many leaders were educated in French schools. In 1925, Hồ Chi Minh, educated in Paris, joined colleagues to create the Revolutionary Youth League, which formed the basis for the Indochinese Communist Party (ICP).

The ICP carried out an unsuccessful peasant revolt in 1930–31 but then continued its armed resistance. When the Imperial Japanese Army occupied Vietnam in 1940, the Japanese retained the French administration, which was aligned with the pro-Axis Vichy regime in France. Hồ Chi Minh formed a new resistance force called the Việt Minh Front that united his Communists with some other non-communist groups in the south to win national liberation.

The First Indochina War

The Việt Minh Front took control of northern Vietnam and parts of the south at the end of World War II. It formed the Democratic Republic of Vietnam with its capital in Hanoi. But the Việt Minh faced resistance from armed non-communist groups in the south. French soldiers loyal to the Free French Government retook many Việt Minh–held areas. In 1946, Hồ Chi Minh agreed to incorporate the Democratic Republic of Vietnam into a French-led Indochinese Union, with South Vietnam a separate republic.

The Việt Minh soon rebelled against French control and launched the First Indochina War in 1946. The French unified central and southern parts of the country as the Associated State of Vietnam. The People's Republic of China and the Soviet Union recognized the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in the north while the United States, Great Britain and other non-communist countries recognized the Associated State.

The capture of the strategic French outpost at Điện Biên Phủ in 1954 by Viet Minh forces led the French government, under domestic and international pressure, to end the war. A cease-fire agreement negotiated in Geneva divided the country at the 17th parallel. Scheduled elections leading to a single national government were never held.

Communist leader Hồ Chi Minh formed the Việt Minh Front to win national liberation against French colonial rule. Above, French prisoners captured in the decisive battle of Điện Biên Phủ leading to the division of North and South Vietnam at the 1954 Geneva Conference. Public Domain.

The Two Vietnams and the Second Indochina War

Hồ Chi Minh consolidated control over the Democratic Republic of Vietnam to impose a rigid communist political system through brutal repression, including mass executions. There were no essential elements of democracy. At the same time, with largescale Soviet and Chinese support, Hồ Chi Minh equipped a national liberation movement, the Viet Cong, with the aim of uniting the country by force.

Hồ Chi Minh consolidated control over the Democratic Republic of Vietnam to impose a rigid communist political system through brutal repression, including mass executions.

In the South, a referendum was held in 1955 that made Ngo Dinh Diem, the previous prime minister, the president of a new Republic of Vietnam. The constitution respected basic freedoms and there was a multiparty system, a free labor movement and civil society. But Diem used harsh authoritarian means to resist the North’s efforts to subvert the government in the South. Over eight years, Diem ordered nearly 100,000 arrests of suspected communists, suppressed religious sects in the countryside and cracked down on Buddhist political dissent in cities.

These actions, however, did not end the communist-led guerilla war or reduce internal political conflict. A military coup, supported by the United States, ousted Diem in 1963, but this only led to a series of short-lived governments with weak public support.

Starting in the late 1950s, the U.S. had steadily increased the number of military advisers and pilots assisting the South Vietnamese army. In 1965, an attack on US ships in the Gulf of Tonkin by the North Vietnamese navy was used as a reason by President Lyndon Johnson to get Congressional approval for much greater military support. The U.S. began heavy bombings in the north and deployed large numbers of troops in the south. At the war’s height, there were over a half million US troops in the country aiding a 1 million-man South Vietnamese army.

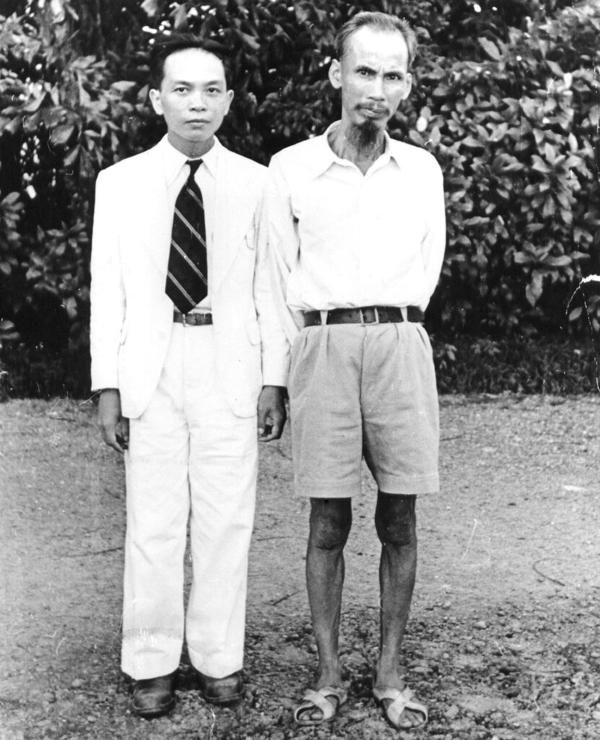

Hồ Chi Minh (above, right) with General Võ Nguyên Giáp in 1945. Together, the two directed the First and Second Indochina guerilla wars to defeat the French and US armies and establish the united Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Public Domain.

In 1968, on the New Year, or Tet, holiday, there was a coordinated series of attacks by the Viet Cong guerilla army, together with North Vietnam’s military, on more than 100 cities and towns in the south. Despite the attacks being largely rebuffed, the scale of the Tet Offensive and losses eroded US public support for an already controversial war. As opposition to it grew, the U.S. agreed to off-and-on negotiations with North Vietnam. Over five years, the U.S. gradually pulled troops out even before an agreement was reached.

The 1973 Paris Peace Accords ended the war with a guarantee of independence for South Vietnam in exchange for complete US military withdrawal. But the Viet Cong’s military campaign continued and the South Vietnamese government fell in 1975.

Post-1975 Vietnam

The country’s reunification under a new name, the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, imposed the north’s communist government on the south. There followed a brutal campaign to consolidate control of the south. There was forced relocation of millions of people and internment of hundreds of thousands in "reeducation camps." Over the next decade, one million people fled the country, mostly by sea.

The communist economy, however, deteriorated to the point of collapse. In 1986, the government launched a reform program (doi moi), which mirrored reforms undertaken in the People’s Republic of China to allow private property, independent economic activity and foreign investments. As in China (see Country Study), reforms helped propel economic growth but the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) retained a tight grip on political power. In 1999, the CVP General Secretary explained the ruling philosophy to the Central Committee Plenum:

Our people won't allow any political power sharing with any other forces [than the CPV]. Any ideas to promote "absolute democracy," to put human rights above sovereignty, or support multiparty or political pluralism . . . are lies and cheating.

The country’s reunification under a new name, the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, imposed the north’s communist government on the south.

For a time, the Vietnamese government eased repression in response to international pressure on human rights issues. But this was directly tied to efforts to obtain membership in the World Trade Organization (WTO). Following accession in 2007, the government increased arrests and harsh sentencing of dissidents, intensified internet censorship and heightened control over religious activities (see Freedom of Religion below).

The Hard Line Continues

In 2011, the 11th Congress of the Vietnamese Communist Party elected the head of the Central Military Commission, Nguyễn Phú Trọng, as General Secretary. The ascendance of Trong, a long-time party leader trained in the Soviet Union, reinforced control by the security and military services over Vietnam’s governance. Trọng was re-elected to another term as general secretary at the 12th Congress in 2016, while a reform-minded Prime Minister was forced to retire.

Trọng’s hard line was evident in a crackdown on free expression. In 2012 and 2013, more than 100 bloggers were arrested, including Phạm Viết Đào, Vietnam’s most popular online commentator. He and others were charged with “abusing democratic freedoms.” New government decrees enacted in 2013 and 2014 gave the state sweeping powers to control speech on the internet and social media and penalize those engaged in “anti-state propaganda” or professing “reactionary ideologies.” Many people were arrested just for trying to attend trials of dissidents, including those tried for their religious beliefs (see below).

Freedom of Religion

Religious pluralism in Vietnam developed as a result of foreign influences and differing state religions practiced over centuries, including the spread of Confucianism, Buddhism and Christianity by conquest, trade and conversion.

Religious pluralism in Vietnam developed as a result of foreign influences and differing state religions practiced over centuries. . . . As in most countries, however, religious practice in Vietnam was mostly characterized by the state imposition of dominant beliefs and practices.

As in most countries, however, religious practice in Vietnam was mostly characterized by the state imposition of dominant beliefs and practices. Under a millennia of Chinese imperial rule, Confucianism was the dominant practice. Under Vietnamese dynasties that began first in the 11th century CE, Buddhism was the official state religion. Vietnam’s last dynastic ruler, influenced by China, again adopted Confucianism.

Under French administration beginning in the mid-19th century, there was relative freedom of religion despite an otherwise heavy-handed rule. It even tolerated to a degree nationalist religious sects that were actively opposed to its colonial control, such as the Buddhist Hòa Hảo. Following France’s withdrawal and the division of the country in the Treaty of Geneva in 1954 (see History above), the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam) allowed religious pluralism and practice, but the state repressed religious groups opposing its authoritarian rule. The Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam) fully co-opted and controlled religious institutions as part of its communist system. Since unification, the Socialist Republic of Vietnam has generally repressed all independent religious practices and religious freedom. Below is a fuller history.

From the Chinese Empire to Vietnamese Dynasties

During the 1,000 years of Chinese rule that began in 111 BCE, Confucianism was the state practice in Vietnam. As a set of ethical and spiritual beliefs ordered around loyalty to the state, one of Confucianism’s contributions was to establish a class of scholar-officials.

During the 1,000 years of Chinese rule that began in 111 BCE, Confucianism was the state practice in Vietnam. . . . In part to separate from Chinese rule, Buddhism was adopted by Vietnamese dynasties as the state religion after expelling the Chinese empire.

Buddhism, a set of ethical precepts and practices to achieve enlightenment founded in northern India, was introduced to Vietnam as a result of trade with Southwest Asia. It increased in influence as Vietnam became more a center of trade. In part to separate from Chinese rule, Buddhism was adopted by Vietnamese dynasties as the state religion after expelling the Chinese empire in the 10th century. Buddhism remained the principal religion thereafter until the 19th century. Then, a new Chinese-supported dynasty under Gia Long imposed a rigid form of Confucianism (Neo-Confucianism) and repressed other religions.

Roman Catholicism was introduced by Portuguese missionaries beginning in the mid-16th century. As the French gained influence in Indochina, the Jesuit priest Alexandre de Rhodes established a mission and gained many converts. Rhodes was expelled in 1630 by Emperor Trinh Tráng for fear of growing Catholic influence, but other missionaries were tolerated. By 1841, the Roman Catholic Church reported a total of 450,000 converts.

From French Protectorate to Two Republics

In response to requests by missionaries to prevent the slaughter of Catholics by Gia Long, Emperor Napoleon III of France ordered an invasion of Vietnam in 1857. Under direct French colonial rule, Vietnam was a place of general religious pluralism and tolerance for Christianity (both Catholic and Protestant), Buddhism, Confucianism and Taoism.

France’s relative tolerance even extended to offshoots of the main religions that acted against both colonial rule and communism.

France’s relative tolerance even extended to offshoots of the main religions that acted against both colonial rule and communism. The largest of these was a syncretic faith called Cao Đài (a blend of Catholicism, Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism founded in 1926). Another was called Hòa Hảo, a Buddhist sect formed in 1939. These religious movements adopted firm nationalist stances that put them at odds with colonial authorities.

After Vietnam was divided at the 17th parallel in the 1954 Geneva Agreement, there continued to be religious pluralism in the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam). Its constitution guaranteed freedom of religion. But successive authoritarian governments repressed religious activists, especially the Hòa Hảo, who opposed the government. Incidents of Buddhist monks carrying out self-immolations in protest of repression affected American public opinion against the war.

In the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam), Hồ Chi Minh’s consolidation of power included the wholesale repression of religious practices and institutions.

In the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam), Hồ Chi Minh’s consolidation of power included the wholesale repression of religious practices and institutions. The Communist Party of Vietnam formally committed itself to atheism. The government forced religious institutions to express loyalty to the state and abide by its control, including approval of religious appointments and activities.

Official Religion in the Socialist Republic of Vietnam

Full state control over religion was extended to the South after the North’s victory in 1975.

The constitution of the unitary Socialist Republic of Vietnam guarantees freedom of religion as do the 2004 and 2016 Laws Regarding Religious Belief and Religious Organization. Such guarantees, however, are trumped by Marxist-Leninist principles of "democratic centralism."

Full state control over religion was extended to the South after the North’s victory in 1975.

Under the constitution, the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV), and particularly its leading structures, the Central Committee and Politburo, have supreme authority over all political, economic and social affairs. Protection of state interests and fulfillment of state objectives supersede individual rights. Vague criminal statutes prohibit behavior that undermines national unity, defames public officials and policies, violates regulations or challenges the political supremacy of the Communist Party.

For example, Article 205a of the penal code states:

Any person who abuses freedom of speech, of the press or of religion, or wrongly uses the rights to assembly, association or other democratic rights to encroach upon the interests of the State . . . shall be subject to . . . a term of imprisonment of between three months and three years.

The central Office of Religious Affairs oversees all religious institutions. It requires registration of religious groups, regulates their use of property and resources, and requires approval for opening branches or engaging in formal religious activities.

The central Office of Religious Affairs oversees all religious institutions. It requires registration of religious groups, regulates their use of property and resources, and requires approval for opening branches. . . .

Many Buddhist and Christian groups, along with the syncretic Cao Đài sect, are registered. But they are either government-created or overseen. Any registered religious organizations must also agree to join the Fatherland Front, an umbrella group of social and political movements linked to the Communist Party.

Despite such restrictions, religious adherence remains high. Up to ninety percent of the population professes religious belief. Fifty percent identify as Buddhist, seven percent as Catholic, two to four percent as Cao Đài, and 2 percent each as Hòa Hảo and Protestant, among other smaller faiths.

Unofficial Religion in the Socialist Republic of Vietnam

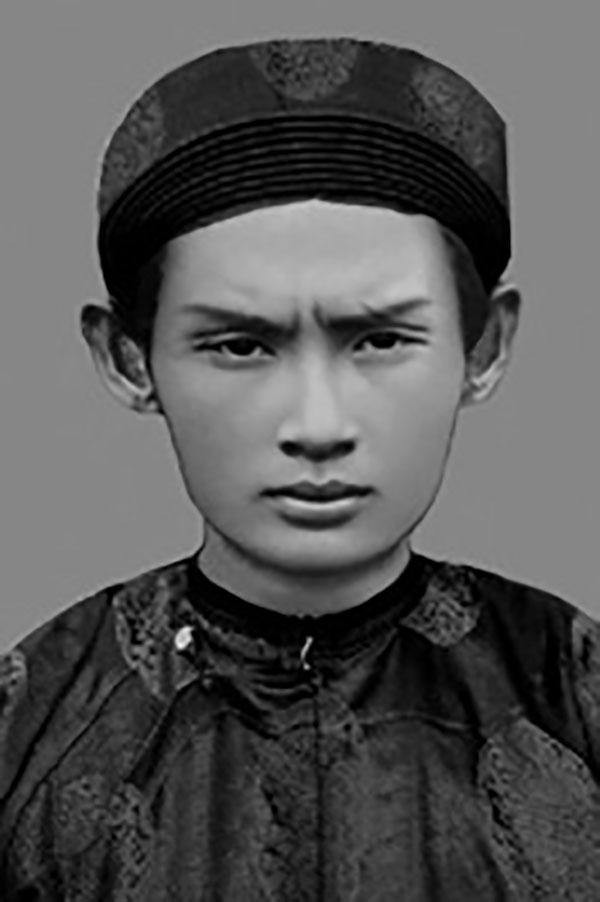

Huỳnh Phú Sổ, founder of the Hòa Hảo Buddhist sect, blended his religious teachings with anti-colonial and nationalist beliefs. Followers have been repressed by governments of both South Vietnam and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Creative Commons. Author: Thuy Trang Nguen.

Religious groups that seek to act independently are denied registration and must practice their religion outside the law. These include the Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam (UBCV), some independently organized Hòa Hảo and Cao Đài groups and many Protestant congregations.

Most independent Protestant worshippers are also ethnic minorities. Their congregations are denied the right to maintain education centers, train officials or operate places of worship. Leaders and individual members of these groups are frequently imprisoned. Congregants are pressured to renounce their faith or switch affiliations to registered churches. Local officials mount campaigns of general harassment.

In one well-known case, five Hòa Hảo members were imprisoned for one to three years in An Giang province in 2000 for planning an unauthorized gathering to mark the anniversary of the death of the sect’s founder (see photo). Four of them had also signed a letter protesting government abuses. The charges against them were " abusing the right to democratic freedoms, disturbing social order and opposing public authorities."

Minor Concessions, Serious Violations

In minor concessions, Vietnamese officials met with Pope Francis in 2014 to “discuss religious freedom and Catholicism in Vietnam.” The government also allowed the UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion, Heiner Bielefeldt, to meet with religious leaders in Vietnam in July. (At the end of his visit, Bielefeldt reported that “serious violations of freedom of religion or belief are a reality in Vietnam.”)

Still, an updated Law on Religion, adopted in 2016, retains full government administrative controls and oversight on religious institutions and activities (see Economist article in Resources). The US State Department continued to designate Vietnam a "Country of Particular Concern" in its Report on International Religious Religion (see Resources for links to UN and US State Department reports).

Current Issues

Vietnam’s communist dictatorship remains stable in its repressive capacity and denial of all rights, including freedom of religion.

In 2021, Nguyễn Phú Trọng was anointed to a third five-year term as General Secretary by the 13th Congress of the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV). As in the previous two five-year terms (see History above), Trong continued to rule with an iron grip, as described below. In July 2024, he died at the age of 80 after 13 years as Vietnam’s most powerful leader; his post is filled by a new president and former minister of public security, Tu Lam.

In staged 2021 elections to the 499-seat Quoc Hoi, or National Assembly, 485 seats went to CPV candidates. (The remaining 14 candidates were technically independent but also formally vetted by the CPV.) At its first session, the legislature elected Trong’s hand-picked candidate, Nguyễn Xuân Phúc, as president. However, reports emerged that Nguyễn planned to challenge Trong in 2026. Within two years, Nguyễn was forced to resign and then arrested for “violations and wrongdoings.”

In May 2024, a more experienced and hardened party leader, General Tu Tam, the Minister of Public Security, was chosen as president. While . . . To Lam was Minister of Public Security, repression of both free expression and freedom of religion remained at a high level.

Another hand-picked candidate of Trong was selected in March 2023, Võ Văn Thưởng. At 52, he was the youngest president in 50 years but lasted just one year. He was forced to resign and arrested as part of Truong’s supposed “blazing furnace” anti-corruption campaign. (A number of Thưởng’s allies thought to be challengers were charged with “wrongdoings.”)

In May 2024, a more experienced and hardened party leader, General Tu Tam, the Minister of Public Security, was chosen as president. While Truong was General Secretary of the CPV and To Lam was Minister of Public Security, repression of both free expression and freedom of religion remained at a high level. As reported by Freedom House, “Arrests, assaults, and criminal convictions of journalists and bloggers continued to be reported in large numbers.” In the period from 2019 to 2023, human rights groups documented the convictions of 60 bloggers and activists for “making, storing, and disseminating materials against the state.” The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) reported at least 19 journalists who were imprisoned in 2023.

The Vietnamese government has increasingly used extra-legal rendition to grab journalists, bloggers and other dissidents from outside the country. In July 2019, Trương Duy Nhất, a blogger working in Thailand for the US-funded Radio Free Asia, was abducted, forcibly repatriated and charged with “abusing his position.” Another rendition case was in 2023. Freedom House writes that in April,

Vietnamese journalist and blogger Duong Van Thai, who had lived as a refugee in Thailand, disappeared in Bangkok. Several days later, Vietnamese state media reported that he had been arrested while allegedly trying to reenter Vietnam; international rights organizations have alleged that Thai was abducted in Thailand.

The journalist was charged with “propaganda against the state” and kept in prison long after his temporary detention was supposed to have ended in August. Thai remained in state custody at year’s end.

Religious freedoms remain severely restricted. The 2016 Law on Belief and Religion reinforced registration requirements and strengthened powers for state interference.

Religious freedoms remain severely restricted. The 2016 Law on Belief and Religion reinforced registration requirements and strengthened powers for state interference. All religious groups and most individual clergy members are required to join a party-controlled supervisory body and obtain permission for most activities. Unsanctioned religious activity is severely punished. In 2022, for example, six members of the Peng Lei Buddhist House were sentenced to a combined 23 years and six months in prison for “abusing democratic freedoms.” In one small concession, the government allowed the Vatican to appoint a resident representative in the country for the first time since 1975.

Vietnam’s harsh regime of repression has earned it a consistent ranking of Not Free in Freedom House’s annual Freedom in the World Survey. That is not likely to change under the new leadership of former head of public security To Lam. In addition to being named president in May, Lam was selected to replace Nguyễn Phú Trọng as general secretary of the Communist Party after Trong's death in July 2024. He thus holds two of the principal four posts in Vietnam's hierarchy of leadership.

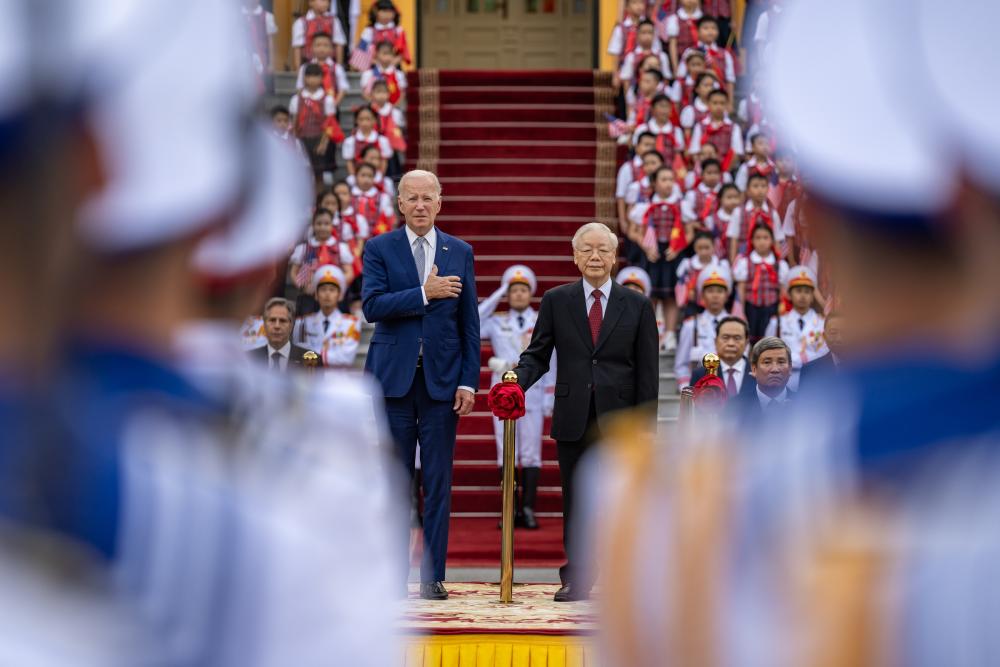

Nguyễn Phú Trọng (above, right) was General Secretary of the Communist Party of Vietnam from 2011 until his death in July 2024, during which time he maintained an iron-grip over the country. President Joe Biden (left) visited Vietnam in September 2023 in an effort to improve relations, but Vietnam also maintains friendly ties with Russia. Its president, Vladimir Putin, visited the country in June 2024. Public Domain.

The content on this page was last updated on .