Summary

Turkey, which lies between the Black and Mediterranean Seas, has a mixed presidential-parliamentary system, but now with dominant executive powers following a controversial 2017 referendum.

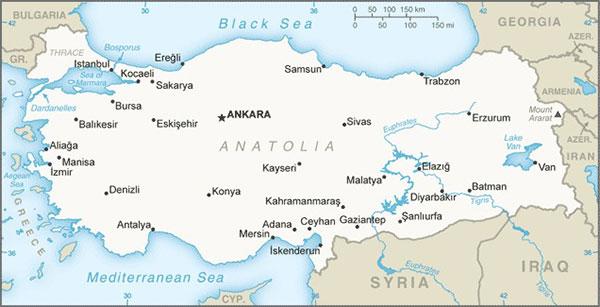

Map of Turkey

Turkey's territory — and history — spans two continents. Most of its territory lies in the historical region of Anatolia in Asia, but its largest city, Istanbul (once known as Constantinople), bridges its European region, eastern Thrace, to Asia Minor.

A citizens' parliament declared an independent republic of Turkey in 1923 following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. The original constitution established a parliamentary democracy and secular republic, although it had several military governments in its first 70 years. Since 2002, Turkey has been led by the Islamist-oriented Justice and Development Party (AKP), which has blurred the separation of state and religion. The AKP’s longtime leader, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (pronounced Er-doe-an), has adopted increasingly authoritarian policies as both prime minister and president, transforming Turkey’s parliamentary system into an executive presidency with few checks on power. Erdoğan won re-election as president in a May 2023 run-off election, held under unfair conditions according to international observers (see Current Issues below).

Primarily Oghuz Turk in ethnicity (75 percent), Turkey has a sizable Kurdish minority (20 percent) among other smaller minority groups. Turkish security forces have repressed the Kurdish minority and fought an armed separatist movement intermittently over four decades. Turkey is a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Alliance and has sought to join the European Union, but its application is suspended over violations of human rights and minority rights.

The country’s population (87 million in 2023) is 18th largest in the world; its territory (785.5 million sq. km.) is 37th largest in area. After 1980, Turkey's economy grew steadily with a mixture of state-interventionist and free market policies, but today it faces severe inflation. According to the International Monetary Fund, Turkey’s nominal Gross Domestic Product (GDP) ranked 18th in the world in projected 2024 total output ($1.11 trillion). GDP per capita is projected to be just 72nd at $12,764 per annum. This is near the bottom among European countries but slightly above the world average.

History

The rich history of Turkey reflects the influence of the broad range of civilizations that have crossed and settled its territory.

In ancient history, Hittites, Persians, Ionians, Lydians, Greeks and Romans (among others) inhabited or conquered parts or all of its current territory. Following the Fall of Rome and the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE, the imperial insignia passed to the Eastern Roman Empire, also known as the Byzantine Empire. Constantinople, today called Istanbul, was its capital. Byzantium held authority over territories in Eastern and Southeastern Europe and the Middle East. As the center of the four Eastern Orthodox churches, Constantinople was known as the “second Rome.” (Eastern Orthodox churches broke communion with the Roman Church in the Great Schism of 1054.)

In the 10th and 11th centuries CE, the Oghuz Turks, who were early converts to Islam and followers of the Sunni caliphate in Baghdad, migrated from Central Asia to Anatolia. The main Oghuz tribes formed the Seljuk Empire, whose ghazis (or horsemen "of the faith") and mamluks (slave soldiers) were renowned warriors. After the Battle of Manzikert in 1071 CE, the Seljuk sultanate gained the allegiance of other Turkic emirates across Anatolia.

The Rise and Fall of the Ottoman Empire

In the 13th century, a new Oghuz dynasty emerged under Osman I, known in the West as Othoman (or Ottoman). Believing himself anointed by God, he conquered much of Byzantine Anatolia to create the Ottoman sultanate.

The Crusades were organized in Europe in part to counter Muslim advances into the Byzantine Empire and to retain Christian control over Constantinople. But in the 13th century, a new Oghuz dynasty within the Seljuk sultanates emerged under Osman I, known in the West as Othoman (or Ottoman). Believing himself anointed by God, he conquered much of Byzantine Anatolia to create the Ottoman sultanate. Mehmet II, the seventh Ottoman sultan, seized additional Byzantium territories in Bulgaria, Serbia, Romania and Greece. He then surrounded Constantinople. It fell in 1471, putting an end to the Byzantine Empire.

The Ottoman Empire joined Seljuk Turk, Byzantine, Persian, Greek and Arab influences under a common rule. Mehmet II declared himself to be the protector of the Greek Orthodox Church while also making Constantinople the center of a revived Sunna caliphate. The Ottoman sultan was accepted as the ruling caliph of Islam by much of the Sunni world after he halted the Persian Safavid dynasty’s spread of Shi’a Islam, which is considered a heterodox doctrine by Sunni Muslims.

A depiction of three Mamluk cavalrymen, a main fighting force key to expansion of the Ottoman Empire. Public Domain.

The Ottoman dynasty lasted six centuries and controlled or dominated territory in the Middle East, North Africa, parts of Central Asia and Southeastern Europe. At its height, the Ottoman Empire extended to southern Hungary and threatened the Austro-Hungarian empire. Defeat at the Battle of Vienna in 1683 ended the Ottoman army’s advance into Europe.

In the 19th century, the Ottoman elite was influenced by the European Enlightenment and the Ottoman court was convinced to undertake reform that reduced the power of the absolute monarchy as well as the dominance of Islamic religious orders. A constitutional monarchy was established in 1876. It lasted only two years. The sultan, Abdul Hamid II, changed course, suspending parliament and re-establishing absolute authority.

The Rise of the Turkish Republic

A movement with both liberal and nationalist ideology called “Young Turks” arose that forced Abdul Hamid II to restore the 1876 Constitution. Three of the movement’s members consolidated power, especially the military; forced the replacement of Abdul Hamid II with a puppet Sultan (Mehmet II); and established a repressive Turkish national government that sparked national revolts within the multiethnic empire. The Ottoman Empire’s European territories were lost in Bulgarian, Greek, Macedonian, Serbian and other uprisings in the Balkan Wars of 1912-13 while revolts among Arabs arose in the Middle East. The Empire’s end was brought about when the three leaders sided with Germany in World War I. The Allied forces of Britain and France defeated not just Germany but also the Ottoman army and occupied much of the empire. This gave impetus to a second more liberal movement of "Young Turks" led by Mustafa Kemal Pasha. They set out to create an independent, modern and secular nation-state oriented toward the West.

Between 1919 and 1923, Mustafa Kemal led a War of Independence to defeat British and French occupation forces. A Grand National Assembly abolished the sultanate and later the Caliphate (formally ending the Ottoman Empire). On October 29, 1923, the assembly issued the Proclamation of the Republic of Turkey. Ankara, where the assembly met, was declared the capital and Mustafa Kemal was elected its first president. (In 1934, parliament anointed Mustafa Kemal as Atatürk, or "Father of the Turks,” as he became more commonly known). Europe recognized Turkey’s independence in the 1924 Treaty of Lausanne.

The Main Law

The "Main Law" . . . instituted a parliamentary democracy and a national, social and cultural policy of "Turkism." . . . Politics were based on principles of liberal democracy. Freedom of speech, assembly and association were written into the constitution.

The "Main Law," drafted by Mustafa Kemal, was adopted in 1924. It instituted a parliamentary democracy (with the president elected by parliament) and a national, social and cultural policy of "Turkism." The constitution rejected a state religion and established a secular state. In an effort to end the embedded privileges of Islamic orders in Ottoman society, the military's National Council had the task of guarding against the influence of Islamism in politics. Education and culture were removed from the religious orders’ control and "Turkified” (including adoption of the Latin alphabet). All Ottoman attire associated with the caste of religious orders was banned.

Politics were based on principles of liberal democracy. Freedom of speech, assembly and association were written into the constitution. In foreign policy, due to its experience in World War I, Turkey was neutral, including during World War II (joining the Allies only in February 1945).

Turkey’s Political Evolution

Before Atatürk's death in 1938, there was effective single-party rule under his Republican People’s Party (CHP). More diverse party politics emerged after his dominance receded. But Turkey's constitution had undemocratic aspects. The military constituted a separate branch of government. Its stated authority to safeguard the secular constitution trumped civilian authority.

On this basis, military leaders carried out constitutional coups in 1960, 1970 and 1980 in response to perceived threats to the state. Still, the army leadership returned the country to democratic government each time (the military's longest rule was three years). In between coups, politics shifted along a basic right-left spectrum, with parties and alignments changing. The 1980s and 1990s saw an economic boom with a mixture of state-interventionist and free market policies. Turkey's economy became closer to the level of Europe.

Islamist Party Gains Majority

In 1995, the pro-Islamist Welfare Party won a plurality in parliament and formed a coalition government with the liberal Democratic Party. In 1997, military leaders, again acting on a perceived threat to the secular state, forced the Welfare Party leader to resign as prime minister. The parliament outlawed the party outright in 1998.

In 2002, a new Islamist party called Justice and Development (AKP) won an outright majority of seats in parliament (367 of 550 seats). With a high 10 percent threshold for entering parliament, only the “Kemalist” party, the Republican People's Party (CHP), also gained seats. In its platform, the AKP abandoned goals for an Islamist state and committed to two main planks: ending corruption and leading Turkey into the EU. The prime minister, AKP leader Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (pronounced Er-doe-an), was once jailed for fomenting religious intolerance. He now led adoption of economic and other reforms to move Turkey towards EU standards.

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan led the Justice and Development Party to election victory in 2002 and has been Prime Minister or President of Turkey ever since, instituting increasingly authoritarian rule. Creative Commons License. Photo courtesy of World Economic Forum.

EU Talks, Constitutional Reform, Elections

EU accession talks began in 2004 but stalled first over the issue of Cyprus, already a member of the EU. (In 1974, Turkey occupied one-third of the ethnically mixed island to prevent its annexation by Greece. A standoff has existed ever since.) Even when Turkey agreed to normalize relations with Cyprus, EU talks stalled on issues of human rights, treatment of the Kurdish minority and Turkey’s failure to acknowledge responsibility for the Armenian genocide in 1915-16 (see Majority Rule, Minority Rights below). In 2016, negotiations resumed as a result of an agreement on migration, but never progressed due to Erdoğan’s increasingly authoritarian rule. His early pledge to achieve EU accession by Turkey's centennial was not met.

The AKP gained its majority from a more religiously oriented electorate and fulfilled its pledge to end discrimination of Islamic religious practice, such as legal bans on wearing head scarves (hijabs) in public institutions, and the military’s intrusion in politics against Islamism.

EU accession talks began in 2004 but stalled . . . on issues of human rights, treatment of the Kurdish minority and Turkey’s failure to acknowledge responsibility for the Armenian genocide in 1915-16. . . . His early pledge to achieve EU accession by Turkey's centennial in 2024 has not been met.

The AKP won national elections handily in July 2007 and the parliament elected the Foreign Minister, Abdullah Gül, as president. He ordered a referendum that year to introduce direct national elections for president and enhancement of the presidency’s powers. It also passed handily.

The 2011 elections introduced greater pluralism. The AKP retained its majority, but had a less-resounding 49.5 percent of the vote. The Republican People’s Party (CHP) retained its 26 percent of the vote and a new party, the Nationalist Movement (which later allied with AKP) gained 13 percent. For the first time, 35 seats were won by members of the Kurdish Peace and Democracy Party after running in direct constituencies to get around the 10 percent threshold.

The first direct presidential election was held in August 2014. It was won by Prime Minister Erdoğan with 51.4 percent of the vote against three candidates. As president, Erdoğan has consolidated power in a manner undermining Turkey’s democracy and respect for majority rule and minority rights.

Turkey’s observance of majority rule and minority rights since independence and since 2002 under Erdoğan and the AKP is in the section below. Erdoğan’s full consolidation of power since 2018 and the country's "backsliding" towards more authoritarian rule is described in Current Issues.

Majority Rule, Minority Rights

The Republic of Turkey was established in 1923 as a secular state and parliamentary democracy after the fall of the Ottoman Empire. But Turkey’s adherence to democratic governance was inconsistent. Prior to the Justice and Development (AKP) party coming to power in 2002, the military had seized power three times and forced other democratically elected governments into resigning on grounds of protecting the state’s secular principles. Even during its periods of democratic rule, minority rights were hardly respected. The Kurdish minority was violently repressed and religious expression and practice was restricted. Still, a pluralist politics and civic sector thrived.

An early meeting of the parliament of the Republic of Turkey. Bain Collection, Library of Congress.

A new constitution adopted through a 2007 referendum moved Turkey from a parliamentary to a mixed presidential-parliamentary system. In 2017, under blatantly unfair conditions, a referendum narrowly passed that formally continued the mixed system but got rid of any real checks on the executive’s power. The constitution maintains a parliament and formally recognizes secularism, minority rights, individual rights and constitutional limits. In practice, protections of basic rights, minority rights and rule of law are not respected.

Initially, the AKP government under the leadership of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan addressed some of Turkey’s democratic failings. It adopted a number of EU reform standards, reduced the military’s role in politics, lifted restrictions on religious practice and improved treatment of the Kurdish minority. But the government reversed policies as Erdoğan consolidated political control. Under his direction, it resumed harsh repression of the Kurdish minority, rejected responsibility for the Armenian genocide and adopted authoritarian methods to maintain power.

As described below and in Current Issues, the abuse of majority rule and minority rights are intertwined.

The Armenian Genocide and Its Legacy

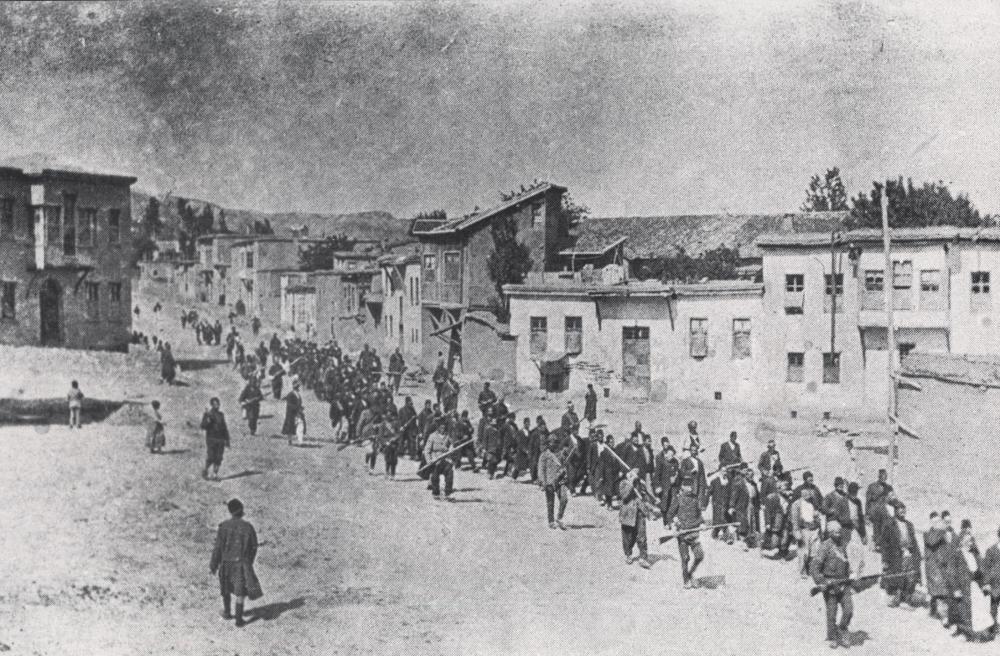

A distinct issue relates to the end of Ottoman rule. As the sultanate’s power weakened during World War I, various nationalities sought autonomy and independence. From 1915 to 1917, Turkish forces and Armenian nationalists fought an internal war marked by massive killings of between 1 and 1.5 million Armenian civilians. The Turkish government has insisted that no targeted killings of Armenian civilians took place during the conflict. Most international scholars, however, agree that the crime of genocide as defined in the 1948 Convention on Genocide took place (see also Essential Principles).

Ottoman soldiers march Armenian men from the city of Kharput to an execution site in 1915. Public Domain.

After Armenia regained independence with the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, its government sought international recognition of the genocide so that the government of Turkey would take responsibility for the crime. Several national parliaments as well as the EU Parliament adopted legislation formally recognizing the Armenian genocide (the US Congress did so in 2019).

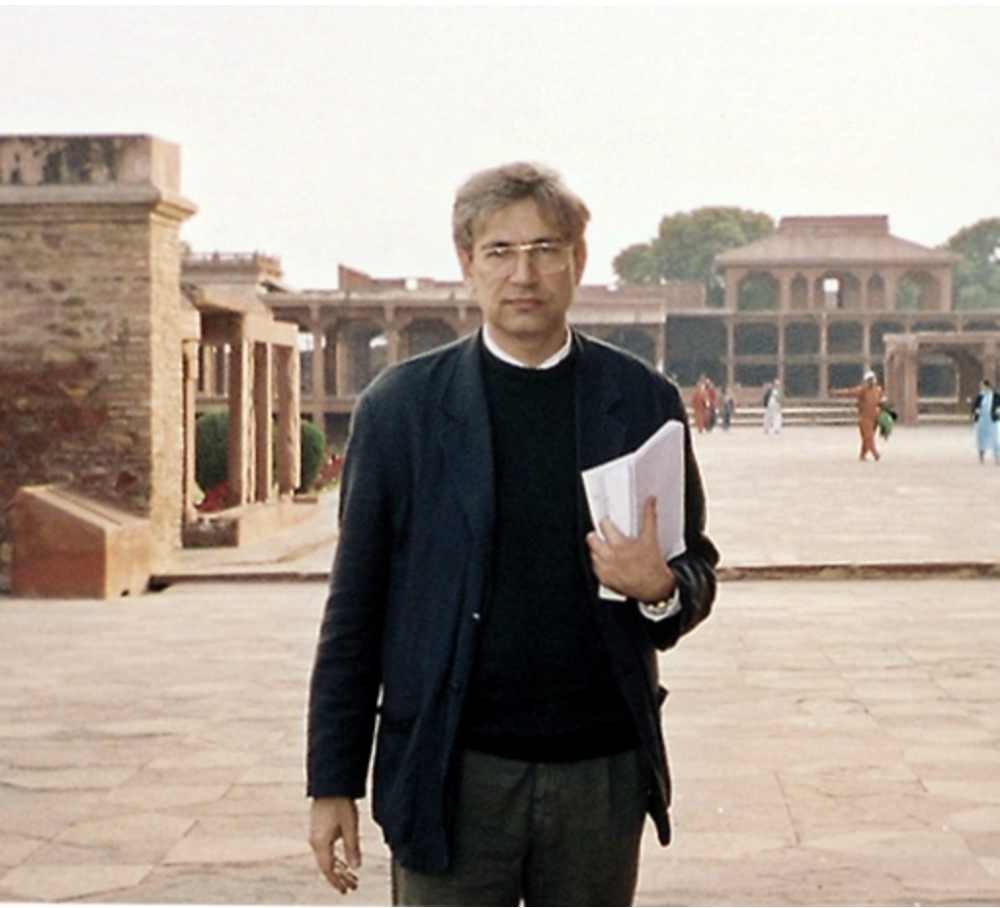

The Turkish government prosecutes those who challenge the official version of events under Article 301 of the Anti-Terror Act. A notable case was that of Orhan Pamuk, the country’s most famous writer, who was awarded the 2006 Nobel Prize in Literature for his depictions of the multi-ethnic and multi-religious culture of Istanbul. In December 2005, Pamuk was arrested and charged with defaming the state by saying that one million Armenian civilians were killed in 1915–16 and 30,000 Kurds were killed by the military in its counter-insurgency campaign in the 1980s and 1990s (see below). International pressure led to dismissal of the charges against Pamuk but Turkey refused an EU demand to rescind Article 305.

The Turkish government prosecutes those who challenge the official version of events under Article 301 of the Anti-Terror Act. A notable case was that of Orhan Pamuk . . . awarded the 2006 Nobel Prize in Literature.

In another case, Hrant Dink, the editor of an Armenian-language newspaper, was sentenced to 6 months’ imprisonment on Article 301 charges. Released on appeal, he was assassinated in early 2007 by a Turkish nationalist. The murder shocked the public. Hundreds of thousands marched through the streets of Istanbul in mourning. The response had a significant effect. President Gül traveled to Armenia in September 2008 on an official visit, the first Turkish head of state to do so. But agreement on establishing diplomatic relations foundered. Following Gül’s visit, there were joint scholarly efforts to examine what happened in 1915–16, but Turkish officials continued to reject the claim of genocide.

The Kurdish Minority

Another minority rights issue is Turkey's treatment of its Kurdish national community. Kurds, residing in a mountainous region that spans Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey, have a distinct language, culture and history dating back two millennia. Fourteen million Kurds live in Turkey alone (20 percent of the population), mostly in its southeastern part that borders Iran, Iraq and Syria.

Since Turkey’s independence, the military viewed the Kurds’ strong self-identity as antithetical to forging a common Turkish nation. In 1982, a military government banned the Kurdish language and started a forced assimilation campaign. In response, the Kurdish Workers Party (PKK) launched an armed insurgency backed by the Soviet Union. Over the next seventeen years, thirty-five thousand people were killed and one million people displaced. Turkish military forces were responsible for most of the deaths but the PKK also carried out widespread terror attacks. The war was suspended in 1999 with the capture of the PKK's leader, Abdullah Öcalan.

Another minority rights issue is Turkey's treatment of its Kurdish national community. Kurds, residing in a mountainous region that spans Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey, have a distinct language, culture and history dating back two millennia.

As Prime Minister, Erdoğan alternated policies between allowing greater use of the Kurdish language and arresting civic activists automatically associated by the government with the PKK. In 2012, however, Erdoğan resumed dialogue with Öcalan, still in prison, and other Kurdish leaders. The PKK agreed to suspend fighting and relocate its forces outside Turkey in exchange for greater Kurdish autonomy and lifting restrictions on the Kurdish language. Many detainees were released by a new law limiting pre-trial detention to 5 years.

Erdoğan reversed course again in 2015, resuming conflict with the PKK due to both electoral challenges (see below) and the civil war in Syria (see Country Study). Turkey allied with armed opponents of Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad but refused to support Kurdish fighters besieged by Syrian government forces as well as by the Islamic State terror group, which had seized territory in Kurdish provinces. After an influx of more than 2 million Syrian refugees fleeing the civil war, including 130,000 Kurds, the government closed its border in 2016 and prevented Turkish Kurds from joining fighters in Syria. The military even attacked Kurdish units fighting the Islamic State, including those acting in conjunction with US forces deployed to the region against ISIS.

Orhan Pamuk, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, in Istanbul. He was prosecuted for stating the number of Armenians killed in 2015-16 and the number of Kurds killed in the military’s counter-insurgency campaign in the 1980s and 1990s. International pressure led to dismissal of the charges. Public Domain.

Increasing Repression of Assembly and Speech

The government also violated basic rights for political and social minorities. In May 2013, tens of thousands of people protested the demolition of Gezi Park in Istanbul’s Taksim Square to build a shopping mall. It was the city’s last remaining large gathering space. After police attacked demonstrators, the protests grew into a national movement against increasing repression and religious restrictions adopted by the government (such as limiting alcohol sales). Erdoğan ordered the police to disperse the protests by force, resulting in eleven deaths and mass arrests. Three hundred protesters were sentenced to significant prison terms.

The Erdoğan regime steadily increased repression on speech and assembly. It charged journalists and hundreds of scholars and authors with defaming the state and violating Article 301 of the Anti-Terror Act (see above). Following Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s election to the presidency in 2014, thousands more faced charges of “insulting the president.” Peaceful protests and strikes were routinely dispersed by force.

In February 2014, parliament approved restrictions on the internet and the government created special courts to pressure social media sites to remove accounts of government critics and posts critical of its policies. Prosecutors also began cases under a blasphemy law. (On blasphemy laws, see also History in Freedom of Expression.)

Tens of thousands protested the demolition of Gezi Park in Istanbul’s Taksim Square in 2013. Protests grew into a national movement but were suppressed by force. Three hundred persons were imprisoned. Creative Commons License. Author: VikiPicture.

Consolidation of Political Power

The government’s initial effort to reduce the role of the military in political affairs earned international praise. But questions arose over Erdoğan’s abuse of the rule of law in relation to two huge conspiracy cases. Over several years, more than one thousand military officers and civilians were arrested on tenuous claims. Most were held for several years in pre-trial detention. In trials starting in 2008, more than 500 were prosecuted on charges of taking part in plots to overthrow different governments. In July 2011, the heads of the army, navy and air force resigned in protest. But this just allowed Erdoğan to make new appointments.

Having established greater control of the military, Erdoğan set out to establish political dominance over law enforcement and judicial agencies. . . . Erdoğan accused prosecutors and police officials of forming a “parallel state” at the direction of a former political ally.

Having established greater control of the military, Erdoğan set out to establish political dominance over law enforcement and judicial agencies. A major reason was that prosecutors had brought bribery charges against the sons of several government ministers in relation to construction projects. Erdoğan’s own son was implicated in the corruption scheme. The ministers had been forced by public pressure to resign.

Erdoğan accused prosecutors and police officials of forming a “parallel state” at the direction of a former political ally, Fethullah Gülen, who leads a popular educational and social religious movement, now from exile in the United States. Erdoğan claimed that Gülen, increasingly critical of Erdoğan’s abuse of power, was trying to undermine him using judicial and police agencies. The government removed or reassigned 5,500 police officers, prosecutors and judges suspected of being “Gülenists.” Bribery charges were dropped against the ministers’ sons.

Electoral Difficulties, Electoral Manipulation

The ruling party was handed a major rebuff in parliamentary elections in June 2015. The AKP garnered just 41 percent support and lost its parliamentary majority. The Republican People’s Party (CHP) held its strong second position (26 percent) and a consolidated Kurdish People’s Democratic Party (HDP) broke the parliamentary threshold at 13 percent.

The government cracked down on dissent by arresting journalists and pressuring others to resign and ordering the closure or takeover of major media outlets.

In this situation, Erdoğan prevented a coalition government from forming and ordered new elections. These were held in November under less fair conditions. The government cracked down on dissent by arresting journalists and pressuring others to resign and ordering the closure or takeover of major media outlets. Under a pretext of responding to PKK attacks, Erdoğan directed sieges of major Kurdish cities that inhibited electoral campaigning.

Erdoğan, contrary to the constitutional requirement that the president be non-partisan, made open appeals to support the AKP. The party claimed a majority of seats in parliament with 49 percent of the vote. The HDP barely surpassed the 10 percent threshold. After the elections, the government heightened its pressure on opposition media, taking over a major news agency and putting the editors of two major newspapers on trial for espionage.

A Failed Coup & the Repressive Aftermath

In July 2016, a faction of anti-government army officers attempted a coup. The haphazard effort confronted massive civilian protests. There were 260 deaths in the violence. Without evidence, President Erdoğan blamed the coup on supporters of Fethullah Gülen (see above).

Erdoğan ordered a full state of emergency allowing rule by decree that lasted two years. He used these powers to purge 110,000 public servants, close schools and universities and arrest upwards of 60,000 people. One hundred and fifty media outlets and 1,500 foundations and civic organizations were closed. Eighty-two of 103 mayors with HDP affiliations were removed, as were other opposition mayors.

Erdoğan then pushed through a constitutional referendum that permanently enhanced his powers by creating an executive presidency with few checks or balances.

Erdoğan then pushed through a constitutional referendum that permanently enhanced his powers by creating an executive presidency with few checks or balances. The referendum passed with only 51 percent support in April 2017, with the “yes” vote likely achieved by fraud. The Organization of Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), which observed the voting, cited numerous irregularities in the tabulation. In June 2017, Erdoğan forced parliament to vote in favor of a constitutional amendment allowing removal of parliamentary immunity. This resulted in the arrest of 12 HDP deputies, including the party’s two top leaders.

Controlled Elections

Erdogan also pushed up the timetable for presidential elections by one year to more quickly implement the constitutional revisions. In June 2018, he won a second term with a majority 52.6 percent of the vote, thus avoiding a run-off election with the main opposition candidate. OSCE monitors again cited irregularities in tabulation and the unfair conditions of the balloting. (The HDP candidate, who received 8.4 percent, ran while still in prison.)

Parliamentary elections were held at the same time. These were won by the People’s Alliance, a coalition formed between the AKP and the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP). It won 344 seats on 53 percent of the vote in an expanded 600-seat parliament. The CHP won 146 seats (22 percent), the HDP 67 seats (11 percent), and a new party, Iyli (Good) gained 43 seats (10 percent).

Current Issues

Since 2018, with establishment of an executive presidency, Turkey's government under Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s leadership has continued to abuse principles of majority rule and minority rights. At the same time, civil society and political opposition continue to organize against Turkey’s authoritarian turn.

Turkey's government under Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s leadership has continued to abuse principles of majority rule and minority rights. At the same time, civil society and political opposition continue to organize against Turkey’s authoritarian turn.

In 2019, political opposition candidates from the Republican People’s Party (CHP) defeated incumbents from the Justice and Development Party (AKP) to win mayor’s races in Istanbul and Ankara, Turkey’s two largest cities, and in ten of the eleven largest urban areas overall. The AKP-controlled Supreme Electoral Council rejected the results in Istanbul and ordered a rerun of the election. The CHP candidate, Ekrem Imamoğlu, won by an even larger margin than in the first election.

The regime responded with targeted arrests of political and civic leaders. Most significantly, the CHP party leader in Istanbul who ran Imamoğlu’s campaign was arrested soon after the election. She was convicted and sentenced to nearly 10 years in prison for “insulting the president” and “spreading terrorist propaganda.” (In April 2022, her sentence was reduced to 5 years by the Supreme Court of Appeals.)

In another case affecting civil society, the government continued to persecute a businessman who helped establish the Open Society Foundation in Turkey, Osman Kavala. He was arrested originally in 2017 and charged with 15 others for orchestrating the Gezi Park protests four years earlier (see above). Acquitted in 2020, he was re-arrested on similar charges. Acquitted again, an appeals court ordered a third trial. He and seven other civic leaders were then convicted of organizing the mass protests. Kavala was sentenced to life imprisonment in April 2022.

Seeking a third presidential term in 2023, Erdoğan faced widespread dissatisfaction with the economy. . . [But the unity opposition candidate] was at a severe disadvantage due to the government’s growing stranglehold over the media, the judiciary, the security forces and the Supreme Electoral Council.

Seeking a third presidential term in 2023, Erdoğan faced widespread dissatisfaction with the economy, which has been in severe crisis following the Covid 19 epidemic. Also, a major earthquake struck southern Turkey that February ─ killing thousands and leaving $34 billion dollars in damage. There was a public outcry over the delayed government response and corruption in the building industry allowing evasion of earthquake-proof standards.

Erdoğan, however, used his state powers to the full to counter his falling poll numbers. In December 2022, Istanbul Mayor Ekrem Imamoğlu, the most popular politician in early presidential opinion polls, was barred from politics by a court for “insulting public officials.” (He remained in office pending appeal but was also charged with three other crimes.) Then, over the next months, Erdoğan used government coffers to respond to economic dissatisfaction. He increased the minimum wage, boosted civil servant salaries and waived the minimum retirement age for 1.5 million workers. In addition, still appealing to “order,” Erdoğan also continued to prosecute the war against the armed Kurdish Workers Party (PKK), a campaign that has resulted in more than 3,000 dead.

Six opposition political parties united behind one candidate, Kemal Kiliçdaroğlu, to face off against Erdoğan in the May 2023 election. The long-standing national leader of the Republican People’s Party (CHP), he ran on a unity platform to end the executive presidency and return democratic rule to Turkey. The older, mild-mannered Kiliçdaroğlu did not generate the same enthusiasm as the younger, more popular Ekrem Imamoğlu.

More significantly, Kiliçdaroğlu was at a severe disadvantage due to the government’s growing stranglehold over the media, the judiciary, the security forces and the Supreme Electoral Council. Even so, Erdoğan received under the threshold of 50 percent needed to win outright in the first round of the presidential election, which was held in mid-May 2023. He was forced to face Kiliçdaroğlu, who had 44 percent, in a run-off election two weeks later. But the third candidate in the race, a nationalist, endorsed Erdoğan. In the second round, Erdoğan claimed 52.1 percent to Kilicdaroglu’s 47.9 percent. International election observers concluded that the elections, while competitive and held without widespread fraud, had severely unfair and unfree conditions.

• • •

Turkey’s near century of democratic politics and culture, however, have a strong legacy. Despite the government’s largescale repression . . . there has been continued organization of political opposition, civil society and independent media.

Under Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s leadership over more than two decades, Turkey has silenced critics, imposed religious conformity and violated minority rights, especially the autonomy and language rights of the large Kurdish community. Majority rule was abused to limit political opposition and consolidate Erdoğan’s hold on state power. Hundreds of opposition leaders and activists from civic organizations and foundations are now imprisoned along with journalists, public servants and Kurdish political activists and leaders. Freedom House dropped its ranking of Turkey below “Partly Free“ to “Not Free” in 2018.

Turkey’s near century of democratic politics and culture, however, have a strong legacy. Despite the government’s largescale repression and dominance over state institutions, there has been continued organization of political opposition, civil society and independent media. In municipal elections held in March 2024, the opposition again won the mayoralties and local councils in Turkey’s largest cities, with the AKP losing ground. Ekrem Imamoğlu won re-election as mayor of Istanbul by a wide margin.

Above, Ekrem İmamoğlu, a leader of the Republican People’s Party (CHP), after winning mayoral elections in Istanbul in 2019. He was charged with “insulting public officials” and barred from running in the 2023 presidential election. Erdogan won against a less popular leader. İmamoğlu was re-elected as mayor of Istanbul in 2024. Public Domain.

The content on this page was last updated on .