The Evolution of Speech

Evolutionary scientists identify the most distinguishing feature of human beings as their capacity for complex language. Above, a depiction of the Book of the Dead from Egypt in Hieroglyphics, one of civilization’s first language systems. Public Domain.

Evolutionary scientists identify the most distinguishing feature of human beings (Homo sapiens) as their capacity for complex language. Theories about when spoken language first developed date to as far back as 100,000 years ago. Recent archeological discoveries date pictographic proto-writing (the precursor of writing systems) to as far back as 40,000 years ago. The first known examples of written language systems are Sumerian, a pictographic language used in southern Mesopotamia, and Egyptian hieroglyphics (both developed around 3200 BCE).

From ancient times to now, opposing forces arose. On one side, individuals wanted to express freely their ideas and opinions in oral and written form. On the other side, rulers wanted to control such expression to maintain power and control over their societies.

The Greek epic poet Homer (ninth or eighth century BCE) advised for free expression without hindrances. Pericles, the great statesman of Athens in its Golden Age (fifth century BCE), extolled freedom of speech as a defining distinction between Athens, a citizens’ democracy, and its enemy Sparta, a military dictatorship. Yet, even Athens restricted some speech. Solon, its first great lawmaker, banned “speaking evil against the living and the dead” (among the earliest known defamation laws). After defeat by Sparta in the Peloponnesian War, the Athenian Citizens Assembly sentenced the philosopher Socrates to death by poison for impiety and corrupting youth to challenge authority.

The Vatican vs. Galileo

Autocrats limited the questioning of their policies, their behavior and their right to rule as well as the questioning of established religions. Public criticism often led to the gallows or worse.

Until the European Enlightenment in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, censorship was the common practice of most states and governments. Autocrats limited the questioning of their policies, their behavior and their right to rule as well as the questioning of established religions. Public criticism often led to the gallows or worse.

In mid-fifteenth century Europe, the introduction by Johannes Gutenberg of the printing press using movable type allowed the mass production of books for the first time. This prompted rulers to impose controls on print publishing. The Vatican was among the main enforcers of censorship. The Sacred Congregation of the Index was responsible for issuing the Index of Forbidden Books. Established in 1559, the list of banned titles grew to thousands of books for reasons of heresy.

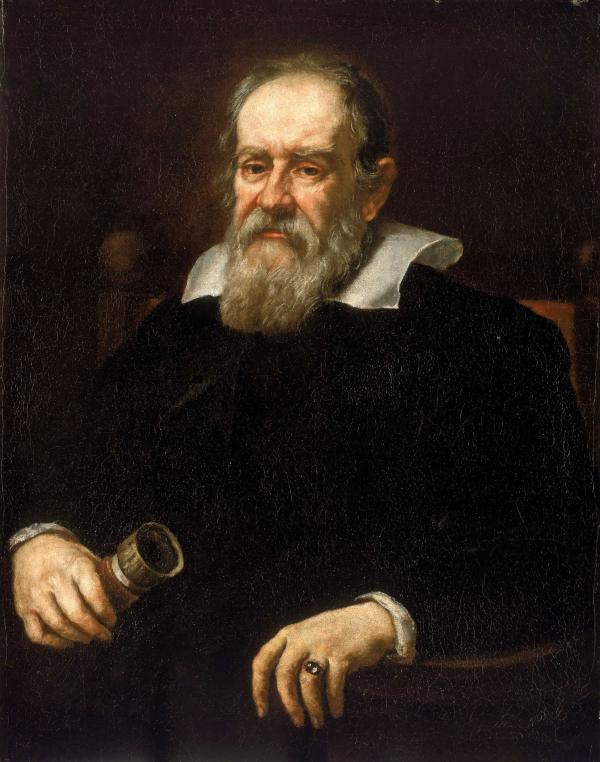

Among the most famous and consequential incidents of repression of freedom of speech was the sentencing of Galileo Galilei by the Vatican for confirming Nicolaus Copernicus’s heliocentric theory of planetary motion around the sun. Public Domain.

One such book was Nicolaus Copernicus's “Regarding the revolutions of the heavenly spheres” (De revolutionibis orbium coelestium). Published in 1543, the book was first banned in 1612 over its challenge to the Church's belief in a stationary, or geocentric, earth, around which the heavens moved. Twenty-one years later, Galileo Galilei (whom Albert Einstein called “the father of modern science”) was sentenced to life in prison for confirming Copernicus's theory of planetary motion around the sun. Galileo's sentence was commuted to house arrest after he recanted his belief in Copernican theory before a papal court. Galileo’s forced recantation and the banning of his own book dampened scientific inquiry and discovery for a century.

The Star Chamber

During the Protestant Reformation, monarchs who broke from the Vatican's authority created their own censorship regimes.

During the Protestant Reformation, monarchs who broke from the Vatican's authority created their own censorship regimes. In Britain, Henry VIII and Elizabeth I, his successor, were in mortal conflict with the Vatican, which supported assassination attempts against both after Henry VIII broke England’s religious adherence to Rome and established a national church. Both monarchs banned books opposing the Church of England and invoked the Court of Star Chamber (a palace court above regular English courts) to suppress opposition to their rule. Elizabeth I also appointed a “Master of the Revels” responsible for censoring public presentations.

The Stuart kings who succeeded Elizabeth I attempted to restore Catholic practices in Britain and asserted the divine right of monarchs over parliament. They used the Court of the Star Chamber to suppress political dissent against them and maintained control over the licensing of printing presses. When the Stuart king Charles I raised an army without approval in his conflict with Parliament, the latter asserted its power over the monarchy and abolished the Star Chamber in 1637. But Parliament decided to institute its own strict press controls through the Licensing Act of 1643. Its restrictions on what materials could be legally published gave rise to an historic debate on free speech.

A Foundational Text on Free Expression

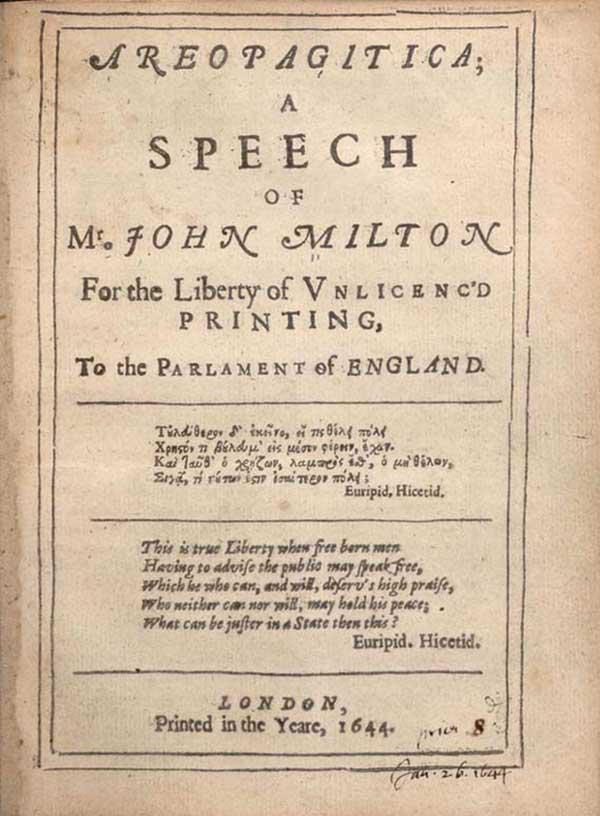

Among the seminal texts for free speech is Areopagitica, an essay by John Milton. Its arguments for unlicensed printing of materials remain a touchstone for freedom of expression advocates. Above, a copy of the original essay distributed for parliamentary debate. Public Domain.

John Milton, best known for his epic poem Paradise Lost, entered the political fray with an essay called “Areopagitica,”(Ár-ēē-o-pa-git-i-ka). Its name refers to an oration from Ancient Greece favoring free speech. In the essay, Milton argued against the Parliament’s adoption of the Licensing Act and for unfettered licensing and free publishing of books and newspapers.

Milton had visited Galileo when under house arrest and witnessed the impact of suppression of speech. Milton’s main argument, novel at the time, is now basic to our understanding of freedom of expression: “Truth is most likely to emerge in a free and open encounter.” This view was rejected by parliament and the Licensing Act passed. But Milton's arguments later found favor among British Whigs who incorporated his principles within the English Bill of Rights during the Glorious Revolution of 1688. While censorship by royal fiat continued, the Licensing Act lapsed and unfettered licensing was practiced.

Milton's Areopagitica became the touchstone for freedom of speech advocates. It has had enduring influence on the liberal tradition in Britain, the United States and countries throughout the British Empire (see Resources).

A Primary Measurement

After the American Revolution, the US Constitution's First Amendment, adopted in 1791, put in place one of the strongest standards for the guarantee of free speech by any constitution, then or now: “Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.”

Freedom of expression became a measure of progress during the Enlightenment. In Europe, Sweden was the first country to abolish censorship in 1766 (although restored soon after). Denmark and Norway did so in 1770. Reflecting the egalitarian spirit of the French Revolution, the “Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen” (adopted in 1789) included both the right to free expression and the right of anyone to own a printing press.

In the American colonies, a major complaint against British rule was the parliament’s adoption of the Stamp Act in 1765 taxing all print materials (any material requiring a stamp or imprint, including licenses). After the Stamp Act’s repeal due to public protest, the King’s press censorship stirred anger further. After the American Revolution, the US Constitution's First Amendment, adopted in 1791, put in place one of the strongest standards for the guarantee of free speech by any constitution, then or now: “Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.”

“The Great Dissent”

The First Amendment is definitive in its language. Yet, the Bill of Right’s protections had both legislative and judicial restraints placed on them. For example, the 1798 Alien and Sedition Acts criminalized false or malicious statements against the government at a time when there was fear of revolt. (America’s print media resumed its free-wheeling style when the law expired in 1801.) Prior to the Civil War, speech opposing slavery was generally prohibited in the South and even in Congress (through its famous “Gag Rule” from 1836 to 1844). Public mobs often attacked abolitionist speeches in the North to suppress speech, giving rise to the Wide Awakes movement to defend Republican Party candidates from mob attack (see Resources).

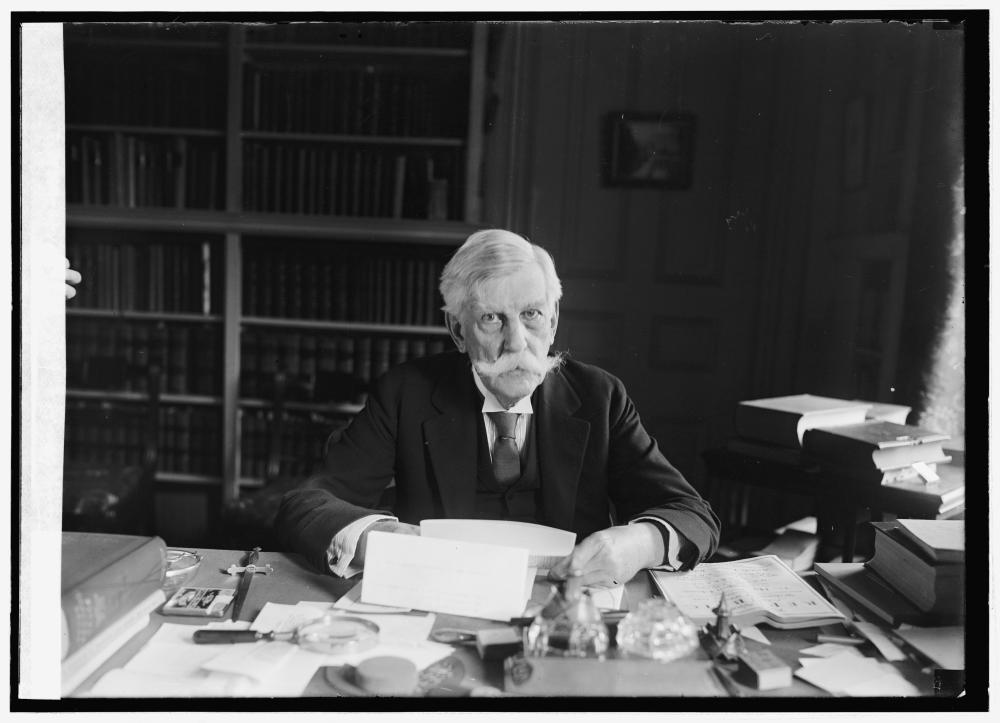

Protections for free speech were constrained by the Supreme Court until the 1950s, when it ruled in agreement with “The Great Dissent” of Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes from 1919 that government should penalize only actions, not speech. Public Domain.

Until the mid-1950s, the US Supreme Court upheld national security laws that restricted speech. They were often applied selectively. In Schenck v. United States (1919), for example, the Supreme Court upheld the conviction of Charles Schenck, a socialist, for distributing leaflets calling for World War I draftees to resist conscription. In the majority decision, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes found in favor of the executive branch’s power to restrict speech on the basis of a “clear and present danger.” He wrote, “The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man falsely shouting fire in a theater and causing a panic.”

But [Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell] Holmes quickly recognized that his “clear and present danger” standard was too open-ended. . . . In a minority opinion that became known as “The Great Dissent,” Holmes wrote, “The ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas.”

This frequently cited quote established a seemingly straightforward standard to restrict speech if it incites public disorder, violence or defiance of the law. But Holmes quickly recognized that his “clear and present danger” standard was too open-ended. In a case heard a year later, the majority upheld convictions against anarchists who had distributed leaflets simply expressing opposition to America’s involvement in World War I.

In a minority opinion that became known as “The Great Dissent,” Holmes argued that his standard should be used only for cases where speech encouraged actions posing “a clear and present danger,” not for expression of opinions or beliefs that the state disagreed with. Reflecting John Milton’s argument from two centuries earlier, Holmes wrote, “The ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas.”

US Standards Expanding Speech

It took nearly forty years for a Supreme Court majority to agree with Holmes’s Great Dissent. Then, in a number of decisions, the Court expanded free expression to the wider realm that today defines free speech standards.

In Yates v. United States (1957), the Supreme Court reversed convictions of 14 Communist Party, USA members for violating The Smith Act, a law barring revolutionary political groups from calling for the government’s overthrow. In Brandenberg v. Ohio (1969), the Court ruled that advocacy of lawlessness was also insufficient to punish speech. Speech had to rise to the level of “fighting words” or incitement to “imminent lawless action.” The Brandenberg case was equally controversial: the decision overturned the conviction of a Ku Klux Klan grand master for threatening violence against Jews and Blacks at a rally but not directly resulting in such violence. In a third decision, National Socialist Party of America v. Village of Skokie (1977), the Supreme Court expanded its doctrine to cover the provocative use of Nazi uniforms, symbols and salutes in a march through a Jewish community where one in six members had survived the Holocaust. And under a majority ruling in Texas v. Johnson (1989), even the burning of the American flag, on its own a violation of the law, is protected free speech if done as a political act or protest.

[In] four landmark cases, the Supreme Court made clear that the most detestable and hateful form of speech . . . was protected if it did not directly incite violence or lawbreaking or did not involve actual plots or actions to carry out insurrection.

In all four landmark cases, the Supreme Court made clear that the most detestable and hateful form of speech, even if intended to provoke rage or gain support for overthrowing the government, was protected if it did not directly incite violence or lawbreaking or did not involve actual plots or actions to carry out insurrection.

In New York Times Company v. United States (1971), the Supreme Court broadened protections for news media from prior government restraints on grounds of national security. It ruled that publishing documents or information about government policies or deliberations could not be prohibited without a “heavy burden of proof” that national security or public order justified it.

An earlier case, New York Times Company v. Sullivan (1964), established protections for news media in cases of defamation. A Montgomery, Alabama councilman had won a libel suit in a lower court over the Times’s publication of a statement paid for by civil rights leaders. (Such suits by Southern officials were common to chill speech in favor of civil rights.) A unanimous decision reversed the lower court and created standards to protect against defamation suits aimed at political intimidation. A plaintiff had to prove “actual malice,” prior knowledge of a claim's falsehood or “reckless disregard” for the truth.

“The Greatest Enemy”

In totalitarian regimes that arose in the 20th century, the principle of freedom of expression was fully negated. Free speech was considered “the greatest enemy” and had to be suppressed.

In totalitarian regimes that arose in the 20th century, the principle of freedom of expression was fully negated. Free speech was considered “the greatest enemy” and had to be suppressed. Such regimes would swiftly take control of all media and publishing houses to make them into state instruments for propaganda. No independent media or publishing was allowed.

Suppression of speech was a key means for consolidating power. In the earliest days of the November 1917 Russian Revolution, for example, Bolshevik leaders imposed strict censorship, wrecked the presses of rival groups and destroyed private libraries of “bourgeois” class enemies. Later, a strict propaganda and censorship bureau was set up that reviewed all text for printed publications and broadcasts and regulated who could be writers and journalists.

In the 19th century, German poet Heinrich Heine wrote prophetically, “Where they burn books, they will ultimately burn people as well.”

In Nazi Germany, Adolf Hitler appointed Joseph Goebbels as Minister of Propaganda immediately after taking power in January 1933. One of his first acts was to incite anti-Semitism. He sparked a massive campaign of book burning events to destroy “non-German” books. At the launching event in Berlin, twenty-five thousand books, mostly of Jewish authors, were burned. (In the 19th century, German poet Heinrich Heine wrote prophetically, “Where they burn books, they will ultimately burn people as well.”)

Totalitarian regimes acted on the principle that truth was the “mortal enemy of the state.” One of Joseph Goebbels’ first acts as Minister of Propaganda in Nazi Germany was a national campaign of book burnings by Jewish authors. Above, an SA soldier throws “un-German” books on the pyre in Berlin in 1933. Public Domain.

Totalitarian regimes were notable also for adopting the practice of the “Big Lie” to justify and perpetuate their rule. Goebbels explained its practice:

If you tell a lie big enough and keep repeating it, people will eventually come to believe it. But the lie can be maintained only for such time as the State can shield the people from the political, economic and/or military consequences of the lie. It thus becomes vitally important for the State to use all of its powers to repress dissent, for the truth is the mortal enemy of the lie, and thus by extension, the truth is the greatest enemy of the State.

Free Thought vs. Totalitarianism

In the history of dictatorships, one finds unimaginable suffering for the sake of free speech but also remarkable courage of individuals who continued to speak and write the truth.

In the history of dictatorships, one finds unimaginable suffering for the sake of free speech but also remarkable courage of individuals who continued to speak and write the truth.

Examples include Reinaldo Arenas, who wrote of the cruel prison experiences he endured in Castro’s Cuba as a gay man sentenced for homosexuality; the Czech dissident Vaclav Havel, who wrote of “the power of the powerless”; Alexander Solzhenitsyn, a Russian political prisoner and the author of The Gulag Archipelago, which documented the USSR’s vast forced labor camp system; and Wei Jingsheng and Liu Xiaobo, Chinese dissidents imprisoned for their advocacy of democracy (see China Country Study and Resources).

For these individuals, and many others, free speech and intellectual freedom were not something to compromise since that meant compromising truth itself. Writers and activists found ways to distribute censored books and publications, broadcast news and spread information through various media. These writers’ and activists’ pursuit of truth and their efforts to overcome censorship have been inspirations for freedom movements around the world. (The United States and other governments attempt to break through censorship barriers of totalitarian regimes through such broadcast stations as Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty, which were sources of independent information and culture during the Cold War in Soviet Bloc countries.)

Article 19: A Universal Standard

As noted in Essential Principles (and in the section Human Rights), the international community created new institutions after World War II to prevent a repetition of worldwide conflict and protect human rights. The most important institution was the United Nations (UN) and among its most important instruments was the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), adopted on December 10, 1948.

The UDHR’s Article 19 established a global standard for free speech:

“Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression.”

Article 19 was used throughout the world as the basis for demanding an end to censorship regimes in dictatorships. However, various human rights instruments, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (adopted in 1966), included exceptions for the temporary restriction of freedoms for reasons of “public order.” Intended as a limited exception for brief periods of emergency, dictatorships often used it to justify general repression.

Article 19 [of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights] established the global standard for free speech: “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression.”

An example was when the government of the Polish People’s Republic imposed martial law in 1981 to suppress the Solidarity free trade union. All of the union’s newspapers were shut down and printing presses seized. The government cited “public order” to justify its actions before the UN Commission on Human Rights even as thousands of activists were being imprisoned for clandestinely publishing or distributing print materials.

The Commission, however, found that the Polish government had acted not to preserve public order (which was never threatened) but to suppress free expression and association. In an important precedent, the Commission condemned the regime’s actions and asserted that when public order is actually at issue any restrictions on freedoms must be limited in time and scope.

Restrictions vs. Unrestricted Freedom

Debates are ongoing about restricting freedom of expression in democracies.

France, Germany and Netherlands, reflecting their wartime histories, have laws against hate speech and public denial of the Holocaust, including in online or digital speech. Germany also bans displays or use of Nazi uniforms, symbols and salutes. In each country, courts protect media freedom and free expression generally, but in contrast with the United States, laws restricting certain speech are seen as essential to prevent a revival of extremist politics.

In each country, courts protect media freedom and free expression generally, but in contrast with the United States, laws restricting certain speech are seen as essential to prevent a revival of extremist politics.

Even so, it remains unclear if they achieve their intended effect. In all three countries, anti-immigrant parties using hate-filled rhetoric have gained significant representation in parliaments. In Netherlands, one such party (whose leader was earlier convicted for hate speech) won a plurality in the 2023 elections. In France, National Rally leader Marine Le Pen (who was prosecuted but acquitted twice for hate speech), succeeded to the second round in presidential elections in both 2017 and 2022, winning 40 percent of the vote in the latter.

In the United States, meanwhile, legal principles protecting speech more broadly are under debate. The Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision in 2010 expanded free speech standards to allow unlimited spending on political elections and advocacy by private persons, corporations and groups. This led to the setting up of “Super PACS” (Political Action Committees) by wealthy individuals and large corporations to spend hundreds of millions of dollars to influence elections and policy. The practice has been taken to its extreme in the most recent election, giving rise to clear cases of oligarchs buying power for their own interests. (For example, Elon Musk, the richest man in the world according to Forbes, spent $250 million dollars to elect Donald Trump as president in 2024 and was quickly named an advisor on matters affecting his businesses. His net worth rose by $25 billion after the election.)

As well, weaponization of hate speech and disinformation in general media and on social media platforms has had harmful effects on election processes and democratic institutions. . . . Disinformation by politicians has even affected the political stability of the United States, a nearly 250-year-old republic.

Also, the government’s removing of the Fairness Doctrine in the late 1980s allowed billionaire magnates to gain control over large print, broadcast and social media empires to propagate political doctrines and influence government without any requirement for equal access to present different viewpoints. Both decisions tipped the balance of free speech in the United States away from the public towards the wealthy. Polling now indicates large support for limiting such political influence (see New York Times article in Resources).

As well, weaponization of hate speech and disinformation in general media and on social media platforms has had harmful effects on election processes and democratic institutions. Authoritarian regimes, taking advantage of the openness of democratic systems, have launched targeted influence operations in the United States and Europe with the aim of destabilizing democracy. Sometimes these operations have had significant impact on campaigns, as in the 2016 presidential race in the U.S., the 2016 Brexit referendum in the United Kingdom and the 2021 German parliamentary election, among others.

Disinformation by politicians has even affected the political stability of the United States, a nearly 250-year-old republic. In 2020-21, for the first time in US history, a defeated incumbent president tried to hold onto power by extraconstitutional means. Using what he termed “free speech rights,” Donald Trump ignored repeated court rulings that found no evidence of election malfeasance and repeatedly lied about the election results. He organized a mass protest on January 6, 2021 on the basis of the lies and incited a mob attack on Congress that threatened the peaceful transfer of power.

In 2023, Fox News, a cable news station that actively propagated the election lies, was held accountable at some level through a civil trial for defaming the Dominion voting machine company (costing it $787.5 million). The former president was also held accountable in a defamation case in which he was found guilty of sexual assault. The victim, whom he accused of lying about the assault, was awarded $84 million (the case is pending appeal).

Trump was not held accountable, however, for his lies about the election. Acting mainly on concerns over inflation and immigration, voters elected him by narrow margins to a second non-consecutive term in November 2024. This may result in serious consequences for free speech. Both before and after being elected, Trump used what are called SLAPP suits (Strategic Litigation Against Public Participation) as well as public threats to intimidate free media coverage of his campaign and administration. Two media outlets settled lawsuits by Trump instead of risking losing litigation in court and Trump appointed an ally to the Federal Communications Commission stating his intent to review broadcast licenses of news media that report negatively on the president. (See also Current Issues in the US Country Study and “How the War Against Press Freedom Could Come to the United States” in Resources.)

Other Free Speech Debates

While the First Amendment applies only to government restriction of speech and media, its protection is seen to apply more broadly. Debates about the practice of free speech within private institutions are ongoing.

For example, many free speech advocates consider speech to be overly restricted at universities with the disciplining of hate speech and actions to shout down, disrupt or disinvite guest lecturers or organize protests that disrupt the regular functioning of the university. Both trends, in their view, limit the purpose of the university as protecting free academic inquiry.

Disinformation is affecting political stability even in democracies. The January 6, 2020 attack on the US Capitol, above, was incited by former President Donald Trump who falsely claimed the 2020 presidential election was stolen. Shutterstock. Photo by lev radin.

Others argue that hateful or harmful speech often is used to bully and intimidate minorities on campus, itself restricting free inquiry by making students feel unsafe to learn or debate. In the main, free speech rights at universities are respected, but there has been recent exception, for example in relation to protests about the Israel-Hamas war. There remains substantial debate and litigation on the topic of free speech limits, both within colleges and universities and in the courts (see Resources and Study Questions).

A worrying phenomenon that directly involves the First Amendment is the restriction by state legislatures of speech and books at public universities and schools.

A worrying phenomenon that directly involves the First Amendment is the restriction by state legislatures of speech and books at public universities and schools. Florida and Texas banned Diversity, Equity and Inclusion programs at public universities. A Florida law bars teacher discussion in school below a certain age of topics related to gender identity and sexual orientation. By the end of 2023, twenty-two Republican legislatures passed “education gag orders” allowing removal of books from school libraries for objectionable content and the barring of teaching history in a way that causes “discomfort.” Some states specifically barred the teaching of The 1619 Project, which seeks to recenter slavery, discrimination and the Black struggle for freedom in teaching the history of the United States (see PEN America’s “Educational Gag Orders” in Resources).

Authoritarian Challenges

The largest challenges to free speech today are in “not free” and “partly free” countries as categorized in the annual Freedom in the World survey. The People’s Republic of China and the Russian Federation are among the most repressive in the “not free” category.

The largest challenges to free speech today are in “not free” and “partly free” countries as categorized in the annual Freedom in the World survey. The People’s Republic of China and the Russian Federation are among the most repressive in the “not free” category.

The communist government of China controls all broadcast and print media and imposes a broad censorship regime on the internet through what is called the “Great Firewall.” In recent years, China has also instituted a “social credit” system that monitors individuals’ positive or negative contributions to the state. In addition, it cracked down on independent media and expression in Hong Kong, where some freedoms had previously survived under terms for transferring authority of the former colony from the United Kingdom to China in 1998 (see Country Study in this section).

In the Russian Federation, state-controlled media dominates and free speech became increasingly suppressed under President Vladimir Putin. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, repression ratcheted up. The last free media outlets closed. There were at least 6,500 arrests in the first 18 months of the war for anti-war expression, including for such symbolic acts as holding up blank pieces of paper in public as symbols of censorship (see New York Times article in Resources). Leading dissidents, such as Andrei Navalny and Vladimir Kara-Murza, were sentenced to long prison terms in prison camps for expressing opposition to the regime and the war. (Navalny died in February 2024 as a result of harsh treatment in an Arctic prison camp. Kara-Murza was freed in August 2024 as part of an international prisoner exchange negotiated by the U.S. and the Russian Federation.) The Russian parliament also passed one of the world’s most severe laws against expression of support for LGBTQ+ rights. It is now being used against persons for appearing to dress in a “gay” manner.

A lone student bravely stood in front of tanks as they entered Tiananmen Square to crush protests on June 4, 1989. The above photo depicts the event and its censorship by Chinese authorities, who have the most extensive censorship regime of any country today. Taboo subjects, such as the 1989 crackdown of Tiananmen Square demonstrations, are not allowed on the internet. Public Domain.

There are many other examples where dictatorships have ratcheted up repression. . . . Two examples are Saudi Arabia and Iran

There are many other examples where dictatorships have ratcheted up repression. In Belarus, there is an ongoing terror campaign against the society for protesting the long-time dictator’s blatant stealing of a presidential election in 2020. Of all countries, Belarus now imprisons the most independent journalists. Two other “not free” examples are Saudi Arabia and Iran (see Country Studies). The former carried out an extrajudicial murder of a dissident living abroad to silence his advocacy for free speech (see Resources for articles on and by Jamal Khashoggi, the dissident journalist). The Iranian government has recently been carrying out a vicious campaign of repression against the Women, Life, Freedom movement.

“Partly free” countries do not control media or repress speech as comprehensively as “not free” countries, but their governments use various means to restrict free expression. The government in Philippines under former President Rodrigo Duterte, for example, used anti-terrorism statutes, defamation suits and tax laws to intimidate independent digital media editors and bloggers (see Current Issues in Country Study). The government of Uganda has increasing intimidation of free media (see Country Study in this section).

Blasphemy Laws and a Fatwah

Blasphemy laws pose a distinct challenge to free speech. Such laws were common in European countries but fell into disuse (see above). Today, they are found generally in countries with dominant Muslim populations as well as others (including some democracies like Indonesia).

A generous reading of the intent of such laws is to encourage respect for religion as a matter of civility. However, they are more often used to impose religious intolerance, enforce a repressive culture and maintain dictatorship. In Iran and Saudi Arabia, blasphemy convictions can result in death penalties. In Turkey, the punishment is less drastic but still chilling of free speech.

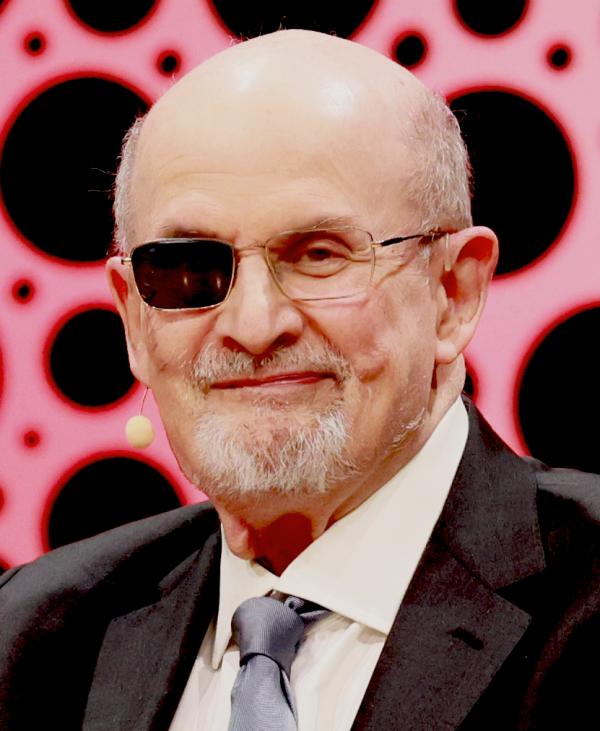

In 1989, Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khomeini issued a “fatwah” against Salman Rushdie for his work Satanic Verses, forcing him into hiding. He was attacked 33 years later by an extremist. Rushdie survived but has lasting injuries. Creative Commons. Photo by Elena Ternovja.

Indeed, blasphemy laws pose a global challenge to freedom of expression. In 1989, Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwah (or religious edict) calling for the assassination of Salman Rushdie, a British writer, for his novel Satanic Verses. Khomeini deemed the book a blasphemous treatment of the Koran and Islamic beliefs.

Rushdie was forced to go into hiding. Book stores carrying his books were bombed; many stopped carrying them. After Khomeini’s death, the fatwah was retracted due to international pressure on Iran’s government. But Rushdie’s movements remained restricted because of ongoing threats on his life. In May 2022, thirty-three years after the fatwah was issued, Rushdie was attacked at a public event in Chautauqua, New York and nearly killed. He survived and continues to speak out in defense of free expression (see articles and a video on Salman Rushdie in Resources).

The Cartoon Wars

Khomeini’s fatwah against Salman Rushdie set a precedent for extremist reaction aimed at suppressing any expression in the world critical of Islam or offending the religious sensibility of devout Muslims. There were many incidents but the most far-reaching were “the cartoon wars.”

Khomeini’s fatwah against Salman Rushdie set a precedent for extremist reaction aimed at suppressing any expression in the world critical of Islam or offending the religious sensibility of devout Muslims. There were many incidents but the most far-reaching were “the cartoon wars.”

In September 2006, Jyllands-Posten, a regional Danish newspaper, published cartoons mocking the Prophet Muhammad. (The Koran forbids any pictorial depiction of Allah or Allah’s Prophets.) Months later, Taliban extremists seeking to topple the elected government in Afghanistan used the publication of the cartoons as pretext to attack a NATO military base where Danish troops were stationed. Protests and attacks on Western embassies spread to a dozen countries. Muslim political and religious leaders in the Middle East called for the Danish prime minister to shut down the newspaper.

Free speech organizations defended Jyllands-Posten’s right to publish the cartoons and argued that restricting speech according to religious sensibility would strike at the heart of freedom of expression. While Denmark’s prime minister did not act against the paper, many Western political leaders called for Jyllands-Posten to issue an apology. An international boycott of Denmark by Arab countries costing the Danish economy several billion dollars led the editors to issue an apology to defuse the international controversy (see Economist articles in Resources).

[T]he challenge remains. Many outlets make declarations they will not be silenced, but most publications choose self-censorship rather than risk the type of intimidation or violence visited on Jyllands-Posten and Charlie Hebdo.

Ten years later, in January 2015, Islamic State extremists carried out a terrorist attack on a French satirical weekly, Charlie Hebdo, in Paris that killed 11 people and injured 11 others. Part of a larger terrorist campaign, the attack on Charlie Hebdo was due to its publication of crude images of the Prophet Muhammad. This time, several million people, including leaders of most European nations, demonstrated in Paris and throughout France to defend freedom of expression. Still, the challenge remains. Many outlets make declarations they will not be silenced, but most publications choose self-censorship rather than risk the type of intimidation or violence visited on Jyllands-Posten and Charlie Hebdo.

The Balance Sheet

According to Freedom House’s annual Freedom in the World survey and its annual report Freedom on the Net, the overall balance sheet for free expression in recent years is trending downward in “Free,” “Partly Free” and “Not Free” countries. Reporters Without Borders has similar findings.

Freedom House describes many efforts, especially by dictatorships, to control the internet within their own borders as well as to encourage disorder abroad through disinformation. The newest tool to monitor and suppress internet posts is Artificial Intelligence, which is also used for disinformation attacks aimed at undermining democracies. Disinformation campaigns range from spreading false claims of harms caused by Covid 19 vaccines to false or misleading messages during free elections.

Democracies face internal challenges of their own. In addition to extremist external pressures to censor speech according to religious sensibility, some countries, such as the United Kingdom, allow wealthy businessmen to easily sue for defamation. Lawsuits are brought against individual journalists who cannot afford expensive legal defense with the aim of intimidating their coverage.

As well, extremist political parties seek power using “populist” themes and misinformation that preys upon economic, social and cultural discontent. When such “populist” themes are used, it usually foreshadows efforts to restrict freedom of expression once power is achieved, as in Hungary.

Another example is Poland, where the Law and Justice party rose to power in elections in 2015 in part by stoking fear of migrants (even though few were choosing to go to Poland at the time). Over eight years, Law and Order then used state media as an instrument of propaganda and attempted to restrict private media through a proposed law barring foreign ownership. In the end, Law and Order’s efforts were unsuccessful. The party lost in the 2023 parliamentary elections (see Current Issues in its Country Study).

The content on this page was last updated on .