Early Forms of Association

People associated in various forms from the beginning of civilization. They did so more freely in the few democracies and republics in ancient times, like Athens and Rome. Elsewhere, the oldest associations were often religious in origin. While religious associations developed independently, often formal institutions would be intertwined with states as representing official religions.

The Middle Ages featured the development of commercial towns and cities as autonomous corporations. They in turn fostered merchants' associations, artisans' guilds and other groupings, including trading monopolies, often by order of the country’s ruler.

For example, in medieval Western and Eastern Europe, the most significant independent institutions were the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches, respectively (see also Freedom of Religion). These maintained their own structure and governance, including in the many states where they represented the official religion.

Yet, they also functioned as quasi-state institutions within each country and exercised great political power as regional or extra-territorial institutions that even organized military campaigns (such as the Crusades). At the same time, the Catholic and Orthodox Churches spawned a variety of affiliated religious societies operating independently to which both clergymen any laypeople belonged. Many survive to this day,

The Middle Ages featured the development of commercial towns and cities as autonomous corporations. They in turn fostered merchants' associations, artisans' guilds and other groupings, including trading monopolies, often by order of the country’s ruler (see also Economic Freedom).

The Freemasons

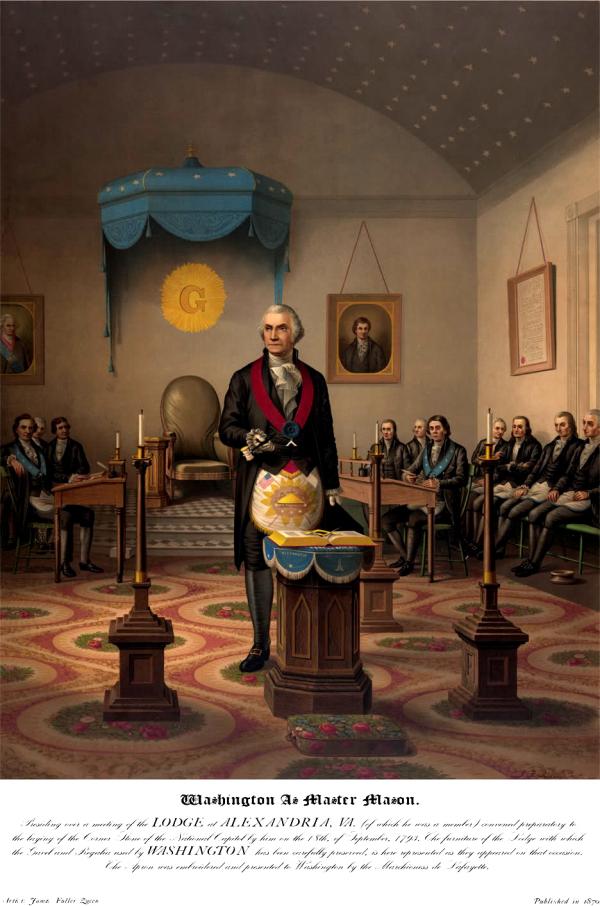

Freemasons' lodges were influential associations during the Enlightenment. Members played roles in the American and French Revolutions, as George Washington (pictured above as master mason of a lodge). Public Domain.

During the Enlightenment in the 17th and 18th centuries, free associations emerged with no corporate, religious or monarchical connection. Among the most influential were the Freemasons. When the skilled trade of masonry declined after completion of the great European cathedrals, masons' lodges, among the earliest associations, evolved from formal centers of apprenticeship and craft development into fraternal orders. They included members from all professions and religious denominations but were heavily influenced by Protestantism. While varied in purpose, most lodges dedicated themselves to the goals of brotherhood, charity and peace.

The first recognized modern order was the Grand Lodge of England, formed in 1717. Freemasonry spread across much of the world, especially the British Empire, and members and leaders of lodges played a significant role in the American and French Revolutions. (Among others, Benjamin Franklin, George Washington and Marquis de Lafayette were leaders of masonic lodges.) The lodges' rituals and secrecy, which had been passed on from practices developed in the Middle Ages, gave rise to conspiracy theories about Freemasonry. But its influence was due mostly to Freemasonry’s model of social organization and networking.

The rise of secret political societies during the French Revolution prompted the British Parliament to pass the Unlawful Societies Act in 1799 and the Combination Acts of 1799 and 1800. These were the first laws of the modern era aimed at repressing free association.

The rise of secret political societies during the French Revolution prompted the British Parliament to pass the Unlawful Societies Act in 1799 and the Combination Acts of 1799 and 1800. These were the first laws of the modern era aimed at repressing free association. The Combination Acts specifically targeted incipient trade unions, known as “combinations.” Freemason lodges were exempt from the ban on condition that they reported their membership and activities to the authorities. (The requirement was repealed only in 1967.)

Civil Society in the United States

The Reformation in Europe — the split in Western Christianity between Roman Catholicism and Protestantism — preceded the Enlightenment and gave rise to different Protestant denominations that favored the autonomy of individual congregations over the hierarchical authority of the Catholic Church. These denominations also fostered a range of associated civic groups, including numerous missionary societies. This tendency was pronounced in America with the religious diversity of immigrant groups, the adoption of separation of church and state as a constitutional precept, and the new country’s general respect for free association.

The open economic environment in the United States also spurred the growth of businesses, corporations and, as a result, commercial and trade associations together with incipient workers' organizations. A number of civic and community groups arose initially out of resistance to America's colonial system and grew after independence.

The nation's new form of self-government relied on all these forms of citizen organization. French politician Alexis de Tocqueville observed in his classic study Democracy in America (1835) that

Americans of all ages, all conditions, [and] all minds constantly unite. Not only do they have commercial and industrial associations . . . but they also have a thousand other kinds: religious, moral, grave, futile, very general and very particular, immense and very small.

Civic organization . . . in the United States only increased. Today, there are about 60,000 local trade unions in 150 union federations and more than 1.5 million registered non-profit associations.

The two centuries since Democracy in America was published support Tocqueville's observations. Civic organization in the United States only increased. Today, there are about 60,000 local trade unions in 150 union federations and more than 1.5 million registered non-profit associations. There are many more that number of unregistered or unincorporated associations, not to mention business, professional and trade organizations.

The British Battlefield

As noted in Essential Principles, freedom of association is both a general and specific right. The more specific right in international law is that of workers to form free trade unions and bargain collectively. The accounts below focus attention on the history of this specific right since the often violent clashes of workers with employers and governments played a unique role in the development of democracies. Great Britain witnessed the first great clash.

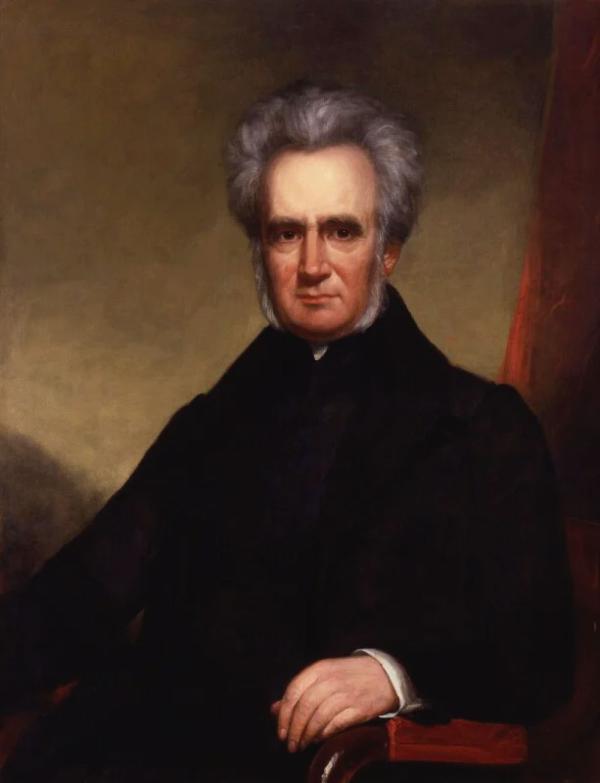

The descriptions of horrible industrial conditions and the repression of workers by radical reformer Francis Place, shown above in a portrait, helped lead to repeal of the Combination Acts in Great Britain. Public Domain.

Political and economic liberalism were intertwined in the late 18th and 19th centuries (see also Economic Freedom). Economic liberalism envisioned employers and laborers entering into individual contracts without interference from the state. For this reason, even liberals who campaigned for abolition of slavery (like William Wilberforce) championed the Combination Acts mentioned above barring workers from forming trade unions.

But early industrialization saw horrific working conditions in the country's new factories. Workers' attempts to improve conditions were harshly suppressed. Often, employers would trick workers into associating in a “combination” to have them repressed. Radical reformer Francis Place described what he observed:

The suffering of persons employed in the cotton manufacture were beyond credulity; they were drawn into combinations [trade unions], then betrayed, prosecuted, convicted, sentenced, and monstrously severe punishments inflicted on them; they were reduced to and kept in the most wretched state of existence.

Penalties imposed by the Combination Acts and related anti-conspiracy laws included imprisonment or deportation to penal colonies like Australia. Early unions in Britain were thus formed mostly in secret.

Today, “Luddite” is used pejoratively to refer to those who refuse to accept technological change. But Luddites’ actions helped bring about real reform.

Workers engaged in desperate acts to improve dismal living standards. The most famous example are Luddites, groups of textile workers who destroyed new machinery they blamed for lower wages and unemployment. Dozens of saboteurs were executed after mass trials. Today, “Luddite” is used pejoratively to refer to those who refuse to accept technological change. But Luddites’ actions helped bring about real reform. Members of parliament recognized that Britain’s harsh laws had driven workers to violent extremes. They repealed the Combination Acts in 1824.

British Labor’s Rise & Fall

After repeal of the Combination Acts, there was a significant increase in the organization of trade unions. In 1833, the General National Consolidated Trades Union was formed with some 500,000 members at its height. Due to ongoing punitive actions against strikes, the federation collapsed and was later replaced by a more informal annual congress, or general meeting, of local trades councils. The first Trades Union Congress was held in 1868.

Employer violence, dismissals and other actions against unions continued into the late 19th century. Workers turned to mass petition campaigns (like the Chartist movement of 1838–48) and creation of a Labour Party to advance their aims. A coalition with Liberals in the first two decades of the 20th century helped achieve some aims. But trade unions in Britain achieved more of their goals when the Labour Party won a full majority in general elections in 1945. The Labour government quickly passed transformative social legislation like national health insurance and broader protections for unions.

Yet, freedom of association continued to be contested. Laws enacted under Conservative Party Prime Ministers in the 1980s and early 1990s again restricted union organizing and activity. Despite these infringements, the Trades Union Congress still has 5.5 million members and bargains for twenty-three percent of the workforce.

The US Labor Movement

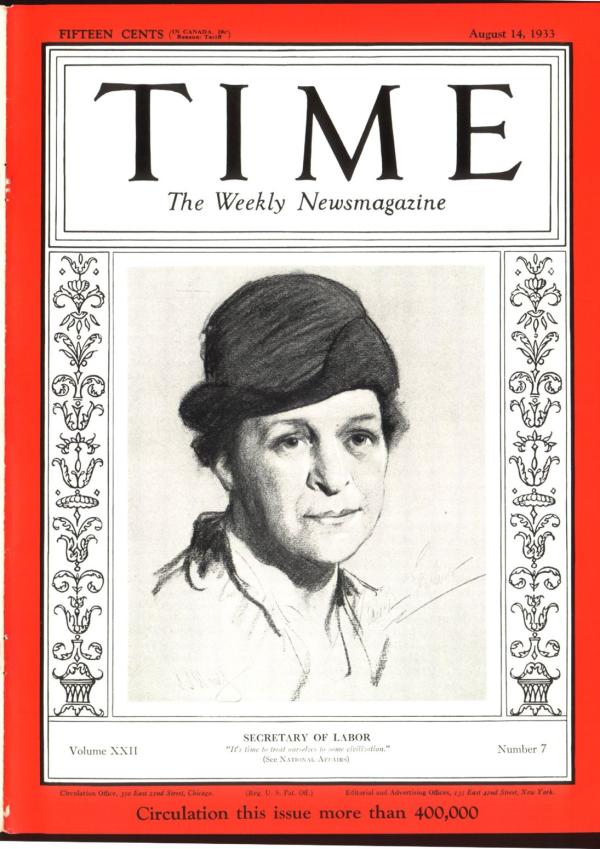

Frances Perkins spearheaded the country’s first state workplace safety laws following the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Fire in New York City. Time magazine featured her on its cover after she became the U.S.'s first woman cabinet member as President Franklin Roosevelt’s Secretary of Labor. Public Domain.

US labor history is similar. As in Great Britain, labor organizations in the United States were met by employer and government resistance, including use of violence, repression and restrictions on union organization. These restrictions were especially directed at unions motivated by anarchist and socialist parties, both of which sought industry-wide or general workers' unions and advocated a radical change in government.

Craft unions, the mainstay of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) that was formed in 1886, were also under severe pressure. But their close-knit organization limited the options of employers to replace workers during strikes. As a result, they could better obtain improvements in wages and working conditions.

When labor concerns gained attention, legislation might be passed to curb mistreatment of workers. The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire of 1911 was the most significant event to raise consciousness. Employers blocked the exits of the factory, thus trapping the textile workers when a fire broke out. One hundred and forty-six workers, mostly young immigrant women, perished in the fire or jumped to their deaths. It remains the single worst industrial accident in US history. In response, the New York state legislature passed the country’s first safety laws for workers.

[U]nion membership increased more than fourfold from 1933 to 1947. But business groups responded by successfully lobbying for passage of laws restricting union organizing. Employers were again allowed to resist unions through “right to work” laws and various other means.

The Great Depression brought about demands for labor reform. President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal changed the legal balance for workers. The National Labor Relations Act of 1935, known as the Wagner Act, established a federally recognized right to organize trade unions and bargain collectively for the first time. The Fair Labor Standards Act, passed in 1938, established the 8-hour workday, 40-hour workweek and a minimum wage as national law.

As a result, union membership increased more than fourfold from 1933 to 1947. But business groups responded by successfully lobbying for passage of laws restricting union organizing. Employers were again allowed to resist unions through “right to work” laws and various other means.

In 1981, President Ronald Reagan followed Prime Minister Thatcher of Britain in using government power to break unions by firing air traffic controllers who went on strike after an impasse in collective bargaining negotiations. Reagan’s action and the appointment of anti-union members of the National Labor Relations Board sent a signal to private employers that the government would allow them to prevent unionization or even break unions.

Over time, union density declined from a high of 33 percent of the workforce in 1955 to around 10 percent in 2023, with only 6 percent represented in the private sector. Still, unions today represent nearly 15 million members and continue to influence national policy, political elections, state legislation and overall social life. A recent increase in strike action has resulted in significant improvements in wages and working conditions for auto workers, longshoremen, package delivery workers and others.

The International Scope

Struggles for freedom of association in all parts of the world share a common history to the United Kingdom and United States. Most countries at first saw governments enact legal restrictions on trade union organization and strikes while employers were free to intimidate workers through dismissal or more violent means. Workers in all countries organized unions to overcome such obstacles and represent their common interests. Unions generally had broad aims: not only to improve legal and working conditions but also to secure social progress, foster greater democracy and achieve greater economic equality.

Workers in all countries organized unions to overcome such obstacles and represent their common interests. Unions generally had broad aims: not only to improve legal and working conditions but also to secure social progress, foster greater democracy and achieve greater economic equality.

In the last 150 years, as in the United Kingdom and United States, free trade unions were central in achieving all three aims in many countries (see Country Studies of Chile and Tunisia in this section and other “Free Countries” in Democracy Web). Often, trade unions would achieve their aims through alliance with social democratic or liberal political parties (see also Multiparty System and Economic Freedom).

Overall, in both the pre- and post-World War II period, free trade unions within established democracies enhanced living standards and workplace safety and defended workers’ democratic freedoms. Basic social welfare and labor standards were adopted in developed and developing countries alike.

The International Labor Organization

The adoption of improved labor standards can be attributed in large part to the work of the International Labour Organization (ILO). As noted in Essential Principles, AFL president Samuel Gompers and European labor leaders had convinced US president Woodrow Wilson and other Allied leaders after World War I to create such an organization. Their belief was that "universal and lasting peace can be established only if it is based upon social justice" (ILO Constitution Preamble).

The ILO adopted a unique tripartite structure that includes representatives of government, business and labor. These three groups worked together to adopt international standards accepted by everyone.

The ILO adopted a unique tripartite structure that includes representatives of government, business and labor. These three groups worked together to adopt international standards accepted by everyone. Initial conventions of the ILO established the 8-hour day and 48-hour week as international norms and called for abolition of forced labor and child labor (work under age 14), institution of maternity leave (a six-week minimum) and establishment of national employment services. Convention No. 87 on freedom of association and Convention No. 98 on the right to bargain collectively became core principles in 1948-49.

ILO Conventions are now established standards in international law. As of 2013, for example, ILO Conventions 87 and 98 had been adopted by 152 and 163 countries, respectively, making these among the most widely accepted international covenants. (The United States Senate, responsible for adopting treaties, has generally been reluctant to adopt human rights and international standards treaties. It adopted just 14 of 189 total ILO conventions and only two of its eight core conventions — on forced labor and child labor.)

Freedom of Association and Totalitarian States

Communist states claimed that workers had no need for free trade unions because their interests were represented by a vanguard Communist Party. In fact, workers had no actual representation and the leadership of the Communist Party monopolized state power. Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin described trade unions as "transmission belts" for party-state directives.

Communist states claimed that workers had no need for free trade unions because their interests were represented by a vanguard Communist Party. . . . Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin described trade unions as "transmission belts" for party-state directives.

The pattern was set soon after the Russian Revolution in 1917. Independent unions were shut down and worker protests were crushed by the Red Army. The most famous was the Kronstadt Rebellion of sailors in 1921. After the USSR was formed in 1923, an all-encompassing trade union federation controlled the workforce. Officials in national and constituent unions were party officials or secret police agents whose chief job was to monitor workplaces. Workers expressing discontent were arrested and sent to camps to perform forced labor in a vast prison system called the GULAG.

Soviet union officials oversaw campaigns in which "super workers" set impossibly high production quotas against which pay scales were set. (They were called Stakhanovites after Alexei Stakhanov, a miner who supposedly mined 102 tons of coal in 6 hours, 14 times the established individual quota.) Workers had to meet the higher quotas set by “super workers” or get less pay. Rather than protect members from exploitation, official unions worked with state employers to drive them to work harder and faster.

Official unions also compelled worker submission by controlling distribution of food, housing, vacations and goods like refrigerators. In democratic countries, some private employers adopted a similar model called "company unionism" and “company towns,” but the Soviet Union’s practices were more systematic, an essential part of the totalitarian state. This system was imposed on satellite states in Eastern Europe and copied as a model in other communist countries such as Cuba, Vietnam and the People's Republic of China (the Country Study in this section).

State-run trade union federations in communist regimes controlled the workforce. In the USSR, they put forward “super workers,” called Stakhanovites, to set high production quotas. The miner Andrei Stakhanov is shown above sometime after his quota-setting exploits. Public Domain.

The "Polish Revolution" & the ILO

One of the ILO's most significant influences on history was its inspiration of Poland's Solidarity trade union (see also Essential Principles). Polish workers rose up in the millions in a nationwide strike in August 1980 with the specific demand that ILO Convention Nos. 87 and 98 be respected. Workers had been informed of these rights through clandestinely printed bulletins and decided to demand their own unions. Solidarity’s success — 10 million workers joined within one month of it being formed — was the first time a free trade union was legally recognized in a communist country.

The "Polish Revolution" was an epochal event that affected workers throughout the Soviet bloc. Soon after a Solidarity-led government formed, massive popular protests led to the collapse of other communist governments in the Central and Eastern Europe.

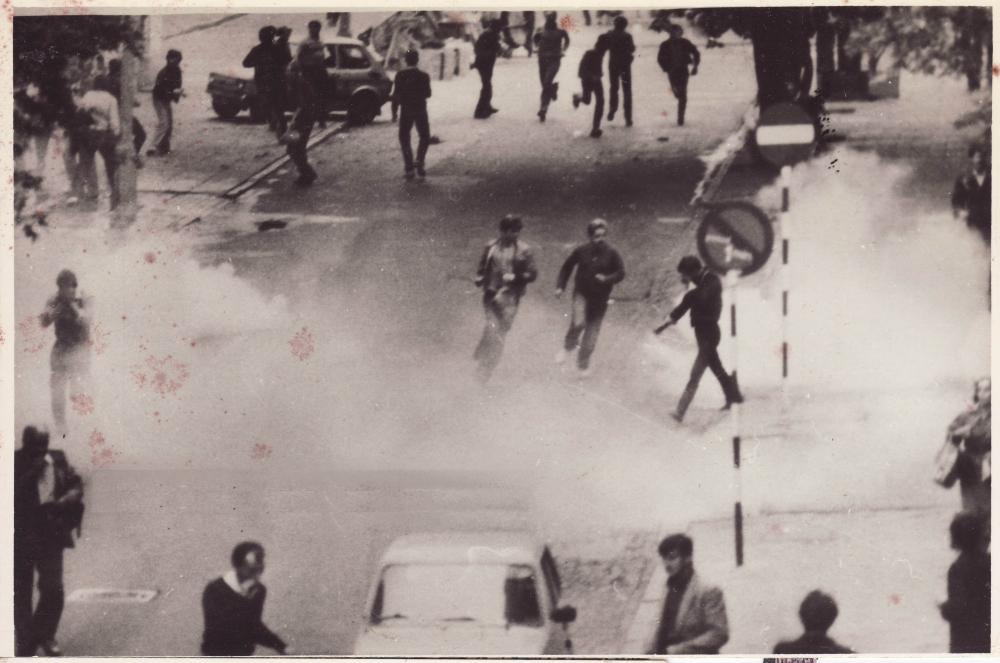

When the Polish government imposed martial law in December 1981 to crush Solidarity — the largest union-busting attempt in world annals — the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions petitioned the ILO for a formal Commission of Inquiry on the violation of freedom of association. Again for the first time, the ILO took formal action against a communist government. The ILO’s actions were binding on Western countries, including the United States, to maintain sanctions on the Polish government until Solidarity was relegalized.

This international support bolstered Solidarity’s underground resistance. In 1988, Polish workers again organized nationwide strikes that put the economy at a standstill and forced the government to re-legalize the union. In further negotiations, Solidarity compelled the government to agree to elections in June 1989 under semi-free conditions. The overwhelming support for Solidarity candidates in those elections led to the communist government’s collapse.

The "Polish Revolution" was an epochal event that affected workers throughout the Soviet bloc. Soon after a Solidarity-led government formed, massive popular protests led to the collapse of other communist governments in the Central and Eastern Europe. The cascade of events in 1989 began with activists distributing clandestine bulletins to workers in Poland explaining their rights under ILO conventions (see also Country Study of Poland).

At its annual conference in 1983, the International Labor Organization (ILO) condemned the Polish government’s use of force against the Solidarity union. Above, a worker demonstration being dispersed in Warsaw, Poland in 1982. Public Domain.

Employers Strike Back

Despite the long tradition of free trade unionism and the widespread adoption of ILO conventions, freedom of association is not secure. Dictatorships are the most frequent violators of workers' rights, but democracies also fall short of international standards.

Despite the long tradition of free trade unionism and the widespread adoption of ILO conventions, freedom of association is not secure. Dictatorships are the most frequent violators of workers' rights, but democracies also fall short of international standards.

One reason is the revival of economic liberalism, popularly known today as neo-liberalism. Its adoption as economic policy has had wide effect in limiting union organization in established democracies and countries that emerged from dictatorship in the 1980s and 1990s. This was especially the case in countries that had state command economies following the collapse of the Soviet Bloc and Soviet Union. As a result, free trade unions failed to take strong root in these new democracies. Even in Poland, free market policies adopted after 1989 led to the weakening of Solidarity.

Internationally, economic liberalism is associated with lower trade barriers and globalization. Mostly, however, neo-liberalism meant multinational companies transplanting manufacturing from countries with high labor standards to countries with fewer or no standards, including dictatorships like China and Vietnam and emerging democracies with few or no protections for union organization and workers generally.

In industrialized democracies, such economic dislocation contributed to the decline of union density. Business groups and conservative political parties grew increasingly hostile to trade unions. A number of countries adopted restrictive laws. For example, the ILO admonished Australia for violating international standards by adopting laws encouraging individual contracts between workers and employers (France adopted a similar law) and a law adopted by the United Kingdom in 2015 restricting strikes. It also admonished the United Kingdom for adopting a law in 2015 restricting strikes.

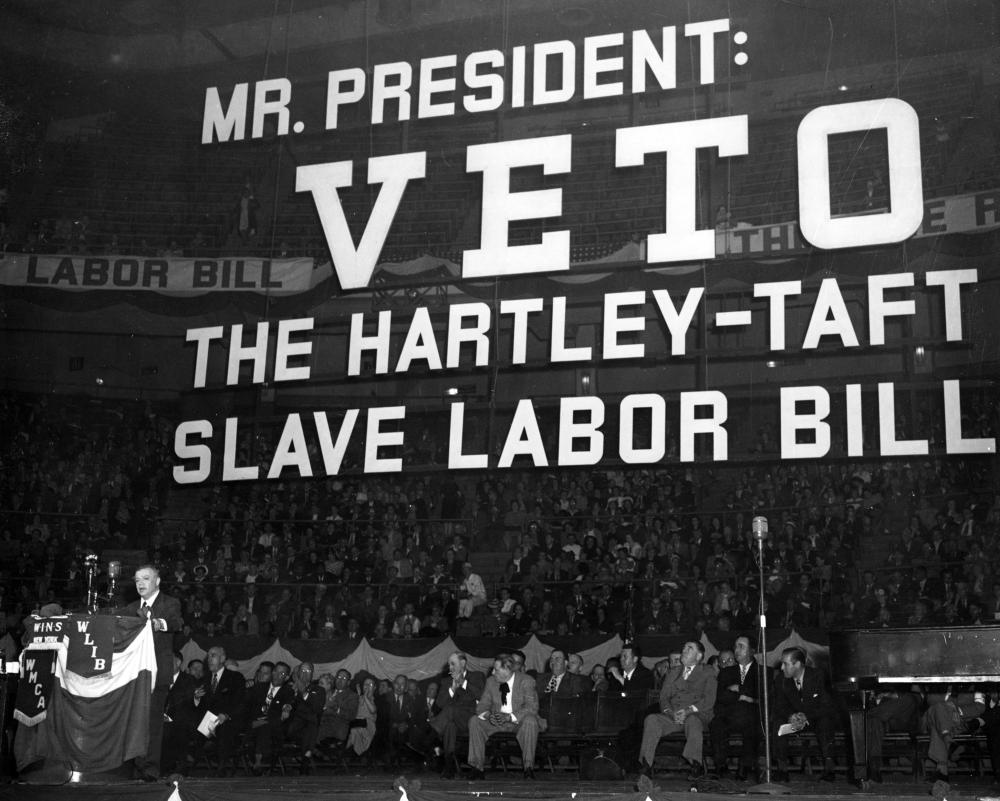

In the United States, the Taft-Hartley Act, adopted in 1948, encouraged individual states to adopt “right-to-work” laws allowing employers to prevent workers from organizing unions. Where such laws are adopted, there is miniscule union representation. As well, when the pro-business Republican Party has held executive power, there is weaker enforcement of the National Labor Relations Act. As a result, the U.S. has among the worst records of freedom of association among industrialized democracies (see reports in Resources).

In the U.S., employers tried to reverse labor gains made during the New Deal. Above, union leader David Dubinsky urging President Truman to veto of the Taft-Hartley Act in 1947 at a union rally. Congress overrode President Truman’s veto, thus allowing “right to work” states and other limits on unions. Creative Commons. Photo courtesy of Kheel Center, Cornell University.

Free market and pro-business economists attribute the decline in unionization rates in developed democracies to an economic shift from manufacturing to services and information technology. Labor economists and trade unionists critique this view, arguing that unfavorable legal and regulatory environments are largely responsible for the trend. They point to higher union density in northern European countries with favorable labor laws.

Recently, newly elected leaders in several industrialized democracies, as in Brazil and the United States, among others, questioned the benefits of neo-liberalism and reasserted the benefits of unionization. They have acted to improve conditions for trade union organizing, collective bargaining and overall worker representation. Such policies have corresponded with growing union activism that has achieved higher wage gains and job security. However, this may not be a broad trend. In the U.S., anti-union policies have returned with the election of Donald Trump to a second non-consecutive term.

Freedom of Association Revisited

All democracies adopted the general “science of association as the mother of science.” Democracies have thrived due to many thousands of groups and organizations, including trade unions, that arose to defend basic rights, assert community values and represent individual, minority and collective interests.

Democracies have thrived due to many thousands of groups and organizations, including trade unions, that arose to defend basic rights, assert community values and represent individual, minority and collective interests.

The ”science of association” proved essential in expanding rights and freedoms that were denied women and minorities. Suffragette organizations, for example, were the major force behind the expansion of the vote to women in most democracies, including the United States and United Kingdom.

Among the most significant post-World War II examples of the power of free association is the US Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. It relied on thousands of local, regional and national Black and multiracial organizations to overcame grave and enduring injustices in the face of violent resistance. Using the strategy and tactics of non-violence and civil disobedience, the movement achieved real advancement of civil rights and political equality for Blacks and other minorities. The Civil Rights Movement has served as a domestic model for other minority groups to expand their rights as well as an international model for national minority and democracy movements (see also History in Majority Rule, Minority Rights).

The Civil Rights Movement has served as a domestic model for other minority groups to expand their rights as well as an international model for national minority and democracy movements.

The exercise of freedom of association, whether in its broad meaning or the specific meaning of worker rights, has been essential to the great expansion of democracy in the post-war period. From the People Power Movement in Philippines to the Reformasi movement in Indonesia, from the No Mas movement in Chile to the Jasmine Revolution in Tunisia in 2011, popular mass uprisings against dictatorship have been the result of freely organized community- and workplace-based associations of citizens working together to bring about democratic change.

The content on this page was last updated on .