Summary

Map of France

France is a republic with a mixed presidential-parliamentary system of government. Located at the western end of Europe across from the United Kingdom, France’s history encompasses periods of absolutism, revolution, empire, constitutional monarchy and republicanism. The country’s most recent constitution (1958) resulted in a period of stable democracy, with Freedom House rating it in the higher range of free countries.

The central event in France’s modern history is the Revolution of 1789, which toppled the absolute monarchy and, in 1792, established the First Republic. The Revolution, however, descended into a period of terror and resulted finally in military dictatorship under Napoleon Bonaparte, who set out to conquer Europe. A constitutional monarchy was established with the Bourbon dynasty restored in 1815 following Napoleon’s final military defeat. It took another 56 years for a stable democracy ─ France’s Third Republic ─ to emerge. That republic ended with Nazi conquest in 1940.

The central event in France’s modern history is the Revolution of 1789, which toppled the absolute monarchy and, in 1792, established the First Republic.

The initial post-World War II republic, faced with internal instability, was replaced by a Fifth Republic in 1958. The new constitution established a powerful presidency balanced by a bicameral legislature. In recent years, France’s democracy has confronted many challenges, including the rise of a nationalist and chauvinist political party challenging for power (see Current Issues).

By area, France is the 41st largest country in the world and Europe's third largest. The total population in 2023 (including overseas regions or departements) was about 67 million people (Europe’s fourth largest). France has a mixed economy that combines a free market with high levels of state spending (62 percent of GDP). France has the world’s seventh largest economy (Europe's third largest) at $3.1 trillion in projected nominal Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for 2024, according to the International Monetary Fund. Its nominal GDP per capita ranks 23rd at $47,359 per annum.

History

France was inhabited from the late Paleolithic era and settled by Celtic tribes (Gauls) starting in the Iron Age. Gaul, the area that later became called France, was conquered in the first century BCE by Julius Caesar and the Roman army. After the collapse of the Roman Empire, a Frankish kingdom established by Clovis I held control over large parts of the territory. In the mid-eighth century CE, Charlemagne expanded it as the Carolingian Empire.

The Kingdom of France emerged as a broader political unit in the late 10th century when kings based in the metropolis of Paris began to assert royal authority over surrounding regions. Over the subsequent centuries, French kings contended with rulers of England across the English Channel who claimed large parts of the northeast. By the reign of Francis I (1515–47), the royal government controlled area near to the borders of modern France.

Wars of Religion and the Edict of Nantes

The rise of Protestantism among French nobility and townsmen during the period of Reformation led to a series of bloody civil conflicts beginning in 1562. The minority who converted to Protestantism (known as Huguenots) were subject to harsh repression and massacres.

Henry IV, a Protestant and the first king of the Bourbon dynasty, defended his succession to the throne with military victories over his Catholic enemies. He converted his religion to gain acceptance of his largely Catholic subjects. In 1598, to prevent further unrest, he issued the Edict of Nantes, which provided Protestants with freedom of worship and civic equality. Henry's son and successor, Louis XIII (1610–43), undermined the Edict and brutally suppressed the resulting Huguenot rebellion of 1625–29. France's next king, Louis XIV (1643–1715), fully revoked the Edict of Nantes in 1685.

Henry IV signed the Edict of Nantes in 1598, presented here to French nobles, granting substantial rights to Protestants, known as Huguenots,. His successor, Louis XIII undermined the Edict and then brutally suppressed the resulting Huguenot Rebellion. Louis IV fully revoked the Edict in 1685. Public Domain.

The Absolutist State

Louis XIV also consolidated absolutist power and centralized the state and economy. His minister of state, Jean Baptiste Colbert, carried out a policy known as mercantilism, which emphasized national self-sufficiency and the accumulation of gold and silver through exports (see also Economic Freedom).

Over the course of the 18th century, the governments of Louis XIV and his successors were beset by fiscal crises due to foreign wars around the European rush for colonial expansion. In this period, many French intellectuals, influenced by Enlightenment ideas, criticized monarchical rule for its lack of rights and representative institutions and for its religious and aristocratic privileges.

In 1788, economic crisis caused by the country’s large debt led King Louis XVI, who had assumed the throne in 1774, to call a rare gathering of a consultative body known as the Estates-General (it had not met since 1614). The Estates General brought together representatives of the nobility, the clergy and lower gentry in Three Estates. When it convened in June 1789, the "third estate" (the gentry) rejected the authority of the first two estates (the nobles and clerics) to declare itself a National Assembly.

The Revolution of 1789

Louis XVI rejected limitations on absolutist authority and the National Assembly's assertion of power, prompting the citizens of Paris to revolt on July 14 and storm the Bastille, a major prison and armory. The uprising took the form of a national revolution.

Louis XVI rejected any limitations on absolutist authority and the National Assembly's assertion of power, prompting the citizens of Paris to revolt on July 14 and storm the Bastille, a major prison and armory. The uprising took the form of a national revolution. (The day is marked every year in France similarly to America’s July 4 celebration.) The National Assembly adopted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, which went further than the original US Constitution in asserting citizens' basic rights.

A majority of delegates to the Assembly hoped to establish a constitutional monarchy, not a democratic republic. The Revolution grew more radical as Louis XVI became more confrontational and the First Coalition of European powers went to war to safeguard French absolutist power. In 1792, the First Republic was established by a new National Convention, elected by general male suffrage. Now dethroned, the king and his wife, Marie Antoinette, were apprehended trying to flee the country and beheaded.

The National Assembly adopted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, which went further than the original US Constitution in asserting citizens' basic rights.

Establishing a republic, however, did not create a stable political system. The most extreme factions of the National Convention instituted a form of revolutionary dictatorship. The period of 1793–94, when Maximilien Robespierre was the dominant leader, is known as the Reign of Terror. Robespierre and his allies, justifying their actions as necessary to save the republic from both domestic and foreign enemies, had thousands of people arrested, tried and executed by guillotine.

From Revolution to Dictatorship

The National Convention ended the Reign of Terror by deposing and executing Robespierre. A new constitution, with suffrage limited by class, was adopted in 1795 creating a bicameral legislature and a five-member executive called a Directory. Challenged by opponents on both the left and right, and beset by foreign attacks, the Directory was dependent on support of the army. After decisive military victories against the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires, which continued to wage war against the French Republic, General Napoleon Bonaparte seized power in a coup in 1799, calling himself the “first consul.”

Above, a painting by Jean-Pierre-Louis-Laurent Houel of the storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789, a date which is celebrated every year in France to mark the beginning of the French Revolution. Public Domain.

Napoleon established Europe’s first military dictatorship. Assuming absolute powers, he proclaimed himself Emperor Napoleon I in 1804. By then, he was engaged in a military campaign to establish a French empire across continental Europe, yet also exporting anti-monarchical principles of the French Revolution. His popular army got as far as Moscow, but was forced to retreat after a failed and costly siege in the winter of 1812. In retreat, the army was routed by Russian forces. Napoleon’s final defeat in 1815 was at the Battle of Waterloo by armies of the British Empire, the Netherlands and Prussia.

The Second and Third Republics

The Bourbon dynasty was restored, but now with a constitution and elected legislature that ostensibly limited royal power. In July 1830, the attempt to reassert absolutism led to a second revolution and replacement of Charles X with his cousin Louis Phillippe, the Duc d’Orelans, and the establishment of a more constrained monarchy.

In 1848, in a year of revolutions throughout Europe, the disenfranchised rose up again to establish France’s Second Republic. It, too, proved brief. Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, the former emperor's nephew, won election as president, but staged a coup as his constitutionally limited single term in office drew to a close. In 1852, he had himself confirmed by plebiscite as Emperor Napoleon III of a Second Empire. Like his uncle, he was deposed following a failed military campaign, this time a crushing defeat in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71).

A famous painting of Eugène Delacrois depicts Liberty leading the people in the second French Revolution of July 1830. Public Domain.

A Third Republic was established as a parliamentary system with restoration of general suffrage. One of the first actions of its military and political leaders, however, was to suppress a challenge by the Paris Commune — representing the more radical tradition of the French Revolution. Despite this violent beginning, the Third Republic was the longest-lasting constitutional system in France's history with a varied multiparty system and alternations in power.

Vichy: A Shameful Era

The Third Republic ended after the Nazi German invasion in 1940. Marshal Henri Philippe Pétain, a hero of World War I and then France’s prime minister, capitulated in an armistice allowing German forces to occupy and administer the country’s north. Pétain became “chief of state” of a puppet regime based in the city of Vichy to administer the southern regions and France’s overseas territories.

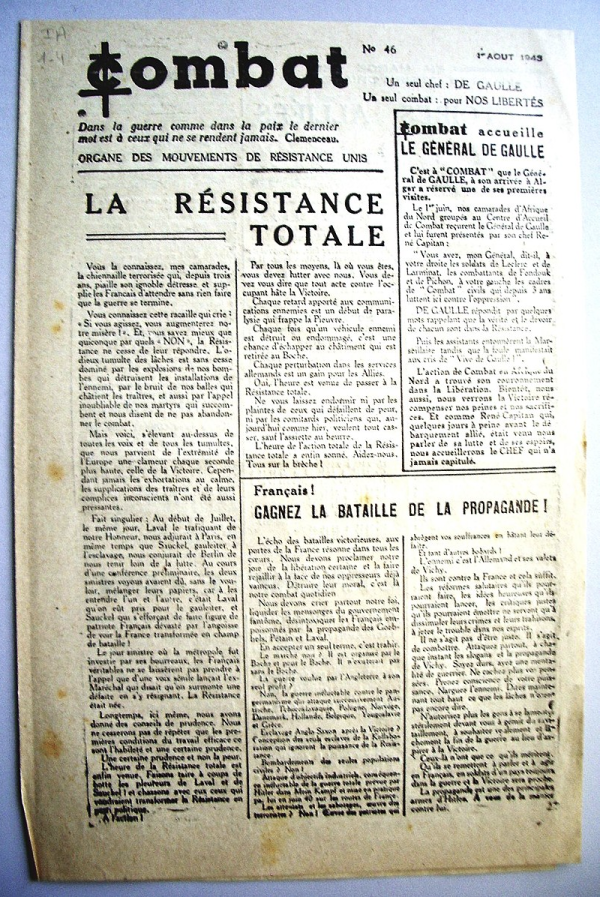

Above, an issue of Combat, the clandestine publication of the united French Resistance during World War II. Public Domain.

The Nazis occupied all of France in 1942, but the Vichy government continued to function, cooperating fully with German forces. Vichy authorities hunted down and executed resistance fighters, contributed French labor to the German war effort, and helped round up hundreds of thousands of Jews for deportation to Nazi death camps, where most perished.

Many French citizens risked their lives to resist the German occupation and to aid the Allies’ war effort through sabotage and guerilla action. General Charles de Gaulle established a government-in-exile in London and a Free French Army, which participated in the liberation of northern Africa and Europe.

The Post-War Republic

The June 1944 Normandy invasion and Allied conquest of France installed a provisional government headed by de Gaulle. It was succeeded in 1946 by France’s Fourth Republic having a similar parliamentary system as the Third Republic.

The Communist Party, active in the wartime resistance, gained strength after the war, raising fears that France might ally with the Soviet Union. France's other political parties united to rebuild the country on a democratic footing, bolstered by US aid through the Marshall Plan. France emerged as a strong democracy and led in the creation of the European Economic Community.

French Colonialism

France was an active participant in Europe’s early race to build colonial empires and imposed harsh rule, slavery and other forms of labor exploitation in many of its colonial holdings to bolster its wealth. France lost its North American possessions to the British in 1763 in the Seven Years War, but retained Caribbean islands and French Guiana in the Western Hemisphere. Napoleon I briefly regained a large section of North America by conquering Spain. In need of money to finance his European campaign, he sold the territory to the United States in the 1803 Louisiana Purchase.

France was an active participant in Europe’s early race to build colonial empires and imposed harsh rule, slavery and other forms of labor exploitation in many of its colonial holdings to bolster its wealth.

In 1794, the National Convention abolished slavery in all its territories due to the successful revolt in what was then called Saint-Domingue, a territory on Hispaniola. Its leader, Toussaint L’Ouverture, was appointed governor in 1801. Napoleon, however, sought to restore slavery and re-subjugate Saint-Domingue. Ultimately, due to the resistance of free Blacks, his invasion force had to withdraw. A final British attempt at conquest was also defeated. The Empire of Haiti was established in 1804, the only instance where a slave rebellion in the Western Hemisphere succeeded in defeating colonial regimes.

Over the course of the 18th and 19th centuries, France colonized parts of Southeast Asia, North and West Africa, as well as islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. France joined Great Britain in dividing the Middle East after World War I, taking over colonial administration for the former Ottoman territories of Syria and Lebanon under a League of Nations mandate. But in the decades following World War II and the adoption of the United Nations Charter, European countries were forced to end their colonial empires due to popular rebellion and domestic and international pressure.

The Haitian Revolution was the only rebellion of enslaved people to successfully overthrow a colonial regime. Auguste Raffet’s illustration of the 1802 retaking of the Crête-à-Pierrot fort from Napoleon’s forces.

Colonialism’s End and the Fifth Republic

The Fourth Republic initially reorganized France's empire as the French Union, granting more autonomy to the colonies. This failed to satisfy demands for independence. Most significantly, guerilla forces in northern Vietnam compelled the French to withdraw from Southeast Asia in 1954 (see Country Study of Vietnam).

Nearly all other French colonies gained independence over the next decade. When Tunisia and Morocco did so in 1956 (see Country Studies), France made a last colonial stand in Algeria, where many French colonists had settled since its invasion in 1830. Right-wing security forces openly threatened the constitutional order over the Algerian war, prompting Charles de Gaulle, the World War II leader, to return from retirement as president at parliament’s request. He established a Fifth Republic in 1958 under a new constitution, approved by plebiscite, that strengthened the presidency’s control over foreign and domestic policy. Algeria won independence in 1962.

Houari Boumediene (right), leader of the National Liberation Army during the Algerian War and later chairman of the Revolutionary Council of independent Algeria. Creative Commons. Museum of African Art (Belgrade).

Under the new constitution, the French Union was reformed into a loose political association called the French Community, similar to the British Commonwealth. This association allowed many colonial territories to declare independence. A number of territories voluntarily remained part of France as overseas departments, collectivities, or sui generis territories. Residents are French citizens who vote in French elections.

Constitutional Limits

Unlike in Great Britain (see History), France’s monarchy had remained absolute. Its consultative assembly, the Estates General, met irregularly only at the invitation of the king. The French Revolution of 1789 toppled the absolute monarchy. A popular National Assembly adopted a sweeping declaration of citizens’ rights that formed the basis of the First Republic in 1792 and all future republics. But the 1789 Revolution did not create a stable democratic or representative system. In the span of 1792 to 1870, France experienced two republics, two restored monarchies, two empires and multiple constitutions.

The French Revolution of 1789 toppled the absolute monarchy. A popular National Assembly adopted a sweeping declaration of citizens’ rights that formed the basis of the First Republic in 1792 and all future republics.

The Third Republic established a more stable and democratic constitutional system and to date is the longest-lasting republic in French history. After World War II, the Fourth Republic, like the Third, had a parliamentary system with multi-party competition. But far right-wing elements within military and security forces undermined the state during the Algerian war for independence.

Charles de Gaulle, whose national authority was preeminent as leader of the Free French Army during World War II, accepted parliament’s invitation to return as president in 1958. He established a more stable Fifth Republic, which he led for the next decade.

The constitution he put forward, approved by public referendum, included larger powers for the presidency, allowing de Gaulle to assert control over the security forces and ultimately end the war in Algeria. The constitution was amended in 1962 to provide direct election of the president. In 2000, a constitutional reform reduced the term from seven to five years. In 2008, the presidency was limited to two full terms.

[T]he 1789 Revolution did not create a stable democratic or representative system. In the span of 1792 to 1870, France experienced two republics, two restored monarchies, two empires and multiple constitutions.

Today, France is a republic with a mixed presidential-parliamentary system of government, also known as a semi-presidential system since the president and members of the National Assembly are elected separately. Under its electoral system, presidential candidates must win by a majority vote in the first round or in a second-round run-off of the two top candidates from the first round. National Assembly candidates who receive 12.5 percent or more in a first round have a second round if no candidate wins by a majority. The candidate with the most votes in a second round (even if not a majority) wins the seat.

The Fifth Republic

The president, serving as head of state, appoints the prime minister and cabinet. The legislative branch retains the right of approval and censure to remove a government, so the Prime Minister is usually appointed from the majority party (or a majority coalition) in parliament even if different from that of the president. The president oversees domestic policy and has responsibility for national security and foreign policy, including command of the armed forces. He also has the power to dissolve Parliament before the end of its term and order new elections as well as to rule by decree in emergencies. The prime minister and cabinet carry out government policy according to laws and a budget proposed by the government but approved by parliament.

The bicameral parliament is composed of a National Assembly and Senate. The Assembly, with 577 deputies (including 11 deputies from overseas territories), is the principal legislative body. Members are elected by district to five-year terms in the manner described above. The Senate has 348 members chosen by an electoral college of elected officials from administrative departments (12 senators represent districts abroad). Senators serve six years (half elected every three years). The Senate may amend bills and initiate some types of legislation, but the National Assembly has dominant power and may overrule in any disagreement. The National Assembly and Senate together (but voting separately) may propose to amend the constitution but any amendment must be passed by referendum.

A meeting of the French National Assembly. Creative Commons License. Photo by Richard Ying and Tanqui Morlier (2009).

Other Constitutional Foundations

The current French constitution proclaims the people's "attachment" to the original Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen from 1789, thereby establishing the rights and freedoms of the citizenry.

Two formal institutions offer institutional checks. One, the Constitutional Council, is made up of former presidents and nine other members (three each appointed by the president, the National Assembly and the Senate). It examines the constitutionality of all laws before they can be signed into law. Since 2010, it also hears appeals on the constitutionality of lower court rulings.

The current French constitution proclaims the people's "attachment" to the original Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen from 1789, thereby establishing the rights and freedoms of the citizenry.

The second institution, the Council of State, is made up of government officers and legal experts. It advises government and parliament on constitutional questions and claims brought by individual citizens.

While there are notable restrictions on free speech, including hate speech and a seldom-enforced prohibition against insulting the president, there is a strong tradition of freedom of expression and assembly, which are additional checks on governmental power. France has vibrant independent media, civic institutions and trade unions as well as a strong culture of critical commentary and public protest.

Political Parties and Elections

Constitutional limits are undergirded by free elections. France’s multiparty system has established a regular alternation of power. Until recently, power alternated between the more conservative Gaullist parties and liberal and socialist non-Gaullist parties.

Charles de Gaulle was succeeded as president in 1969 by a hand-picked successor. Non-Gaullists won the next three presidential elections (in 1974 by centrist Valery Giscard d’Estaing and in 1981 and 1988 by Socialist Party leader François Mitterrand). Jacques Chirac, leading the Gaullist Rally for the Republic (RPR), retook the presidency in 1995 and was re-elected in 2002. In the latter election, he decisively defeated a far-right candidate, Jean Marie Le Pen of the National Front, who had come in a surprising second in the first-round ballot. The RPR’s Nicolas Sarkozy succeeded Chirac in the 2007 election. The Socialist Party candidate Françoise Hollande defeated Sarkozy in 2012.

Constitutional limits are undergirded by free elections. France’s multiparty system has established a regular alternation of power.

French presidents mostly preside over parliaments controlled by the same party. But the mixed presidential-parliamentary system led to periods of divided government (called in French cohabitation). This occurred twice in Mitterrand’s 14-year presidency and once during Chirac’s presidency. More recent elections have seen the breakdown of traditional party alliances (see also Current Issues below). Following Socialist Party victories in the 2012 presidential and parliamentary elections, the president and party lost support due to the initial failure of its economic policies and then adoption of market-oriented policies. This inconsistency led to steady declines in the polls.

Support for the Gaullist RPR party dropped as its former leader, Nikolas Sarkozy, was convicted in 2016 and 2021 on charges of corruption related to the 2007 election. It was the second time a former RPR president was convicted by French courts. In 2011, Jacques Chirac was found guilty of diverting public funds while Mayor of Paris and given a suspended sentence due to his age. Sarkozy has not served any sentence pending appeals.

Alliances and Their Constraints

France was a founding member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 1949 and of the European Coal and Steel Community in 1952. The latter eventually evolved into the European Union. These institutions established strong treaty obligations, as did membership in the Council of Europe, another post-war body, which requires adherence to the European Convention on Human Rights.

President Charles de Gaulle withdrew France from NATO's military command structure in 1966, but France rejoined in 1995 and has since participated in joint NATO actions in the Balkans, Afghanistan and Libya (where it took the leading role in 2011). France recently has joined other NATO countries in supporting Ukraine with military and other support against a Russian invasion.

France plays a leading role in the European Union, especially in supporting steps toward greater economic, monetary and political integration. In a 2005 referendum, however, French voters rejected a proposed EU constitution due to perceived encroachments on sovereignty. Nevertheless, France, under Gaullist, Socialist and centrist governments, have backed a strong EU.

A Dominant National Issue

The state’s treatment of immigrants and their descendants, especially Muslims from former colonies in the Middle East and North Africa, has been a dominant national issue in the post-war period and continues to raise issues of constitutional limits.

The state’s treatment of immigrants and their descendants, especially Muslims from former colonies in the Middle East and North Africa, has been a dominant national issue in the post-war period and continues to raise issues of constitutional limits.

For one, the constitution is not clear on the equal status of immigrants, an issue of high prominence due to high levels of migration from former French colonies, especially those in Africa (see also Current Issues). Roughly 10 percent of the population is foreign-born, mostly from Muslim countries. Many others were born in France to immigrant parents. Urban rebellions in 2005, 2007 and more recently prompted by killings of youth by police have highlighted the issue of immigrants’ rights against police violence and the generally poorer economic conditions and lower social status of immigrant communities.

Religious traditions of Muslim immigrants are often pitted against the French state practice of laïcité, a principle of strict separation of religion and state in public life. A 2011 law banned all full-face coverings in public, including niqabs worn by some Muslim women. A law that generally bans religious displays in state-funded settings, such as public schools, was then applied to ban the more commonly worn head scarves (hijabs) that do not obscure the face. While the European Court on Human Rights upheld the 2011 law, France’s highest appeals court held that a young woman fired from a public day care center for refusing to remove a traditional hijab violated France’s anti-discrimination employment laws.

In 2015 and 2016, multiple terrorist attacks carried out by the Islamic State killed 130 people and wounded many more. There was a public response that raised general suspicions of all immigrant communities. Then-President Hollande ordered a temporary state of emergency that allowed security agencies to surveil, carry out warrantless searches and close down mosques and organizations suspected of promoting violence. Following renewed extremist attacks, new laws were adopted in July 2021 that codified these state of emergency practices and also included holding individuals in custody without charge, restricting home schooling and allowing permanent monitoring of organizations and religious institutions.

Human rights organizations joined Muslim community organizations in criticizing the breadth of the security laws. (Freedom House lowered France’s civil liberties score due to the laws’ passage and use.)

Despite the strength of right-wing anti-immigrant sentiment, the discriminatory practices of French policing and the economic and social challenges faced by immigrant communities, France has also demonstrated a high level of integration of people of color at different levels.

In 2020, as part of international Black Lives Matter protests following the murder of George Floyd in the United States, large demonstrations called for an end to ongoing police discrimination and racism and also for addressing the country’s colonial history. Far-right political leaders defended France’s colonial history and attacked such appeals, often with racist rhetoric, during French presidential and legislative campaigns (see below). President Macron reflected several sides of the issue. He issued a formal apology for French colonialism on a state visit to Algeria but he criticized what he called the “import of wokeism from the American university.” As part of that criticism, Macron, who frequently celebrates France’s republican heritage, nevertheless partially rehabilitated Napoleon at an anniversary occasion as reflecting French heritage.

Despite the strength of right-wing anti-immigrant sentiment, the discriminatory practices of French policing and the economic and social challenges faced by immigrant communities, France has also demonstrated a high level of integration of people of color at different levels. A majority rejected the National Rally chauvinist platform in recent elections in favor of parties with a republican tradition of politics based on equality and inclusion (see also below). Among the national institutions reflecting this inclusiveness in a symbolic manner is the football, or soccer, French national team. It was celebrated for winning the 2018 World Cup and for returning to the finals at the 2022 World Cup tournament. A majority of the team, including its main stars, is made up of children of immigrants from a wide range of Francophone countries and overseas French departements.

Current Issues

The 2017 elections marked a fundamental change in political party allegiance, political party structure and French politics.

The 2017 elections marked a fundamental change in political party allegiance, political party structure and French politics.

In polls, the main Gaullist and Socialist parties had lost much of their support due to perceptions of corruption and the failure of neo-liberal austerity policies. A little-known Socialist Party politician, Emmanuel Macron, at age 40, led a new centrist political party, En Marche (Forward), to landslide electoral victories in presidential and parliamentary elections on a centrist platform of reform. In the presidential contest, the Gaullist, Socialist and other traditional party candidates failed to make the second round. Instead, Macron was pitted against the extreme right National Front (NL) candidate, Marine Le Pen, who had succeeded her father as head of the party (see above). Macron won a landslide victory (66 to 32 percent).

En Marche then won 350 of the 577 seats in the National Assembly elections two months later, unprecedented for a new party. Traditional right-wing parties gained just 133 seats, while left-wing parties fell to 44 seats.

The National Front’s candidates won eight seats in the first round in the legislative elections and led in many districts but lost all second-round contests due to other parties’ unity in voting against National Front candidates. Still, Le Pen’s success in the presidential election, the National Front’s first-round showing and its eight-seat foothold in the National Assembly demonstrated heightened political support for an anti-immigrant and national chauvinist political party that aligned with far-right parties in Europe (including even Vladimir Putin’s United Russia).

Above, election posters during the First Round of the 2022 Presidential Election. Two candidates, Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen, succeeded to the second round. Creative Commons License. Photo by Jean-Paul Corlin.

During Macron’s first term, large protests occurred against the government’s adoption of environmental economic policies. In 2018, truckdrivers, known as Gilets Jaunes (Yellow Vests), blocked roads and streets for weeks over increases in diesel fuel taxes aimed at reducing fossil fuel emissions. The government was criticized for its use of force against the protests. Protests and strikes in 2019 blocked the government’s free-market oriented plans to reorganize France’s complex pension system.

None of the traditional parties regained their prior strength in the 2022 elections. In the second round of the presidential race, Macron, with his party renamed Renaissance, was rematched against Le Pen, whose party is now called National Rally. The latter was a rebranding of the National Front intended to “soften” the party's extremist image. Macron again won a large victory by 58 to 41 percent.

After his re-election, Macron pushed for market-oriented policies favoring business, limiting unions and restructuring France’s public expenditures.

Parliamentary elections in June saw support for Macron’s rebranded party drop to 245 seats, while the center-right Gaullist Republican Party won 64 seats, a significant drop from 2017 but enough to support a majority coalition with Renaissance in the National Assembly. A new left-wing coalition called the New Ecological and Social People’s Union (NUPES) emerged as the second largest bloc with 133 seats. But National Rally, under its new name and running on a populist platform, surged. It won 89 seats.

After his re-election Macron pushed for market-oriented policies favoring business, limiting unions and restructuring France’s public expenditures. In early 2023, the president sought to change the pension system again, this time by proposing to raise the retirement age to 64 from 62. Macron's proposal prompted large protests and demands by France’s major unions for consultation, as required by law. The government refused dialogue.

Emmanuel Macron, president of France, who won successive five-year terms in in 2017 and 2022 against Marine Le Pen, leader of the chauvinist National Rally. Creative Commons License. Author: Duosdebs1.

Fearing that the government’s proposal would not pass in the National Assembly, the prime minister invoked a little-used constitutional procedure (Article 49.3) to allow the new law to come into force without a direct vote. The constitutional procedure has a democratic override through an immediate no confidence motion. Article 49.3 has previously been used to give lawmakers a way not to vote for unpopular measures but then not to force out the government. (The government survived the no confidence motion.) Protests and strikes continued for months, but there was no reconsideration of the law.

Invoking Article 49.3 was within France’s constitutional limits but stretched France’s political norms. It reflected President Macron’s practice of wielding power in an uncompromising manner. President Macron’s public support dropped considerably.

In July 2023, France was rocked by violent protests over a period of weeks following the killing of a Muslim immigrant by police. Visual footage of the killing showed police shooting an unarmed man driving away from a traffic stop. In response to earlier protests in 2005 and 2007, the government committed itself to increased efforts to improve education, job training, employment and social services for immigrant communities.

In the aftermath of these demonstrations, President Macron called the killing “inexcusable” but denied that there existed “two Frances,” calling for “civility.” In the first week of protests, the authorities arrested and convicted 600 participants in the riots of assault and damage to property. No significant reforms were adopted.

Anti-immigrant sentiment appeared to grow within the electorate. The center and center-right parties adopted harsher policy proposals to restrict immigration similar to those of National Rally.

Anti-immigrant sentiment appeared to grow within the electorate. The center and center-right parties adopted harsher policy proposals to restrict immigration similar to those of National Rally. As elections approached for the European Parliament, the legislative body of the European Union, the National Rally and other far right nationalist parties campaigned on harsh anti-immigrant, anti-Islamist and chauvinist platforms and again made clear their alliance with other far-right parties in Europe. They openly appealed for policies explicitly benefitting only “real French” (meaning white) citizens, including to end birthright citizenship for children of immigrants and base citizenship on prior family heritage.

European Parliament elections held in early June 2024 showed a significant drop in popular support for Emmanuel Macron and his centrist movement. National Rally won a plurality of 31 percent to 15 percent for Macron’s new bloc, Ensemble (Together), and 14 percent for the Socialist Party. In light of his party’s large defeat, Macron dissolved the National Assembly and called for immediate national elections in late June in a risky bid. He hoped the citizenry would rebuff the far-right in more meaningful national elections.

In the first-round of voting on June 30, however, the National Rally (NR) won a plurality of 33 percent, raising fears that it would lead the government. Still, NR candidates won just a few dozen seats outright by majority vote in the first-round of district voting (one by Le Pen). Five hundred and one seats went to a second round, with 311 of the seats having three- or four-way run-offs in France’s two-round qualifying system.

In the second round election on July 7, the National Popular Front won 180 seats and Ensemble won 159 to deny National Rally the leading position in French politics. . . . [But t]he final result left the Assembly fractured. No political party had won a majority of seats [and there was no] clear majority coalition since Macron refused cooperation with the left parties.

All the Left parties (Greens, Socialists, France Unbowed and Communists) united in what it called the New Popular Front (NPF), a name reminiscent of the political bloc in the mid-1930s that defeated fascist-aligned parties. The NPF came in second with 28 percent in the first round. For the second round, the NPF and Ensemble (which received 21 percent) agreed to an even broader front to withdraw third- and fourth-place finishers in the first round and back each other’s candidates with the most votes from the first round in order to defeat National Rally candidates.

In the second-round election on July 7, the NPF won 180 seats and Ensemble won 159 to deny National Rally the leading position in French politics (it won 142 seats). There was record 66 percent turnout in both rounds, including a high participation rate of young voters. Although the French public celebrated the defeat of the far right and victory of republican parties, the National Rally emerged as a strong unified political force with enhanced position in the National Assembly.

The final result also left the Assembly fractured. Unlike in past elections that resulted in divided government, no political party had won a majority of seats, without any clear majority coalition since Macron refused cooperation with the left parties. In September, after considerable delay, Macron nominated Michael Barnier, leader of The Republicans, the rump Gaullist Party that won just 31 seats. In doing so, he had consulted Marine Le Pen to arrange a tacit understanding that National Rally would not immediately call for a no confidence vote. He then named a cabinet made up of Renaissance and Republican members to signify his political realignment to the right. The New Popular Front, despite winning the most seats, are now in the opposition.

The government did not last the year. In December 2024, the National Rally, dissatisfied with the proposed budget, initiated a no-confidence motion supported by the left parties. Macron nominated a center-right ally, François Bayrou, and a new cabinet made up of mainly center-right parties. The government survived a first no-confidence test in February after presenting a budget, aided by left-oriented members of the parliament after Bayreu indicated he would revisit the retirement law that had caused political conflict.

A demonstration against the pension reforms of Emmanuel Macron, which were organized over six months. The poster refers to the constitutional provision, Article 49.3, allowing the legislation to proceed without a vote in the National Assembly. Creative Commons License. Photo by Jules*.

The content on this page was last updated on .