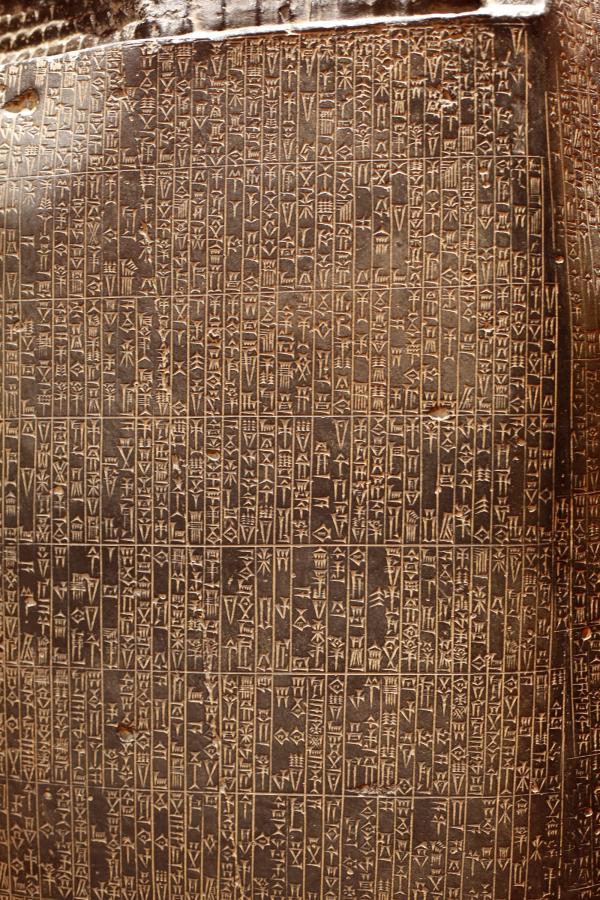

The Code of Hammurabi

The Code of Hammurabi is considered the earliest written legal code for a government. It established that government (in this case that of the King of Babylon, Hammurabi) should be subject to a set of his own proscriptions. A depiction in the Musee de Champollion. Creative Commons. Photo by Vigneron.

In general, the “rule of law” for much of human history and for most empires, monarchies or principalities was the law of fiat. Whatever a ruler declared was law for his or her subjects. Often, this meant strict interpretations of religious law alongside secular law to govern human behavior and civil interaction. The earliest written legal code for a government was the Code of Hammurabi, dating from 1750 BCE.

The King of Babylon, Hammurabi, needed to unite his disparate realm. He decided to establish common rules of conduct, commerce and devotion to the king under a system overseen by judges. Much of the code is severe: many minor crimes were punishable by death or corporal punishment. Nevertheless, it was noteworthy for introducing basic ideas that government (even absolute monarchy) should be subject to law, that laws should be based on public rules, not secret or divine ones, and that law should be applied by judges separate from the ruler (see also Essential Principles).

The Example of Athens

The ancient city-state of Athens surpassed most governed territories in the development of rule of law principles. Under the system of Athenian democracy, magistrates and jurors were drawn by lottery from the Citizens’ Assembly, which was composed of all free-born adult males. All citizens had the right to bring both private and public matters before the courts. In commercial law, the principle of binding and enforceable contracts was applied. This meant that law, not the use of force, determined the resolution of disputes — a principle that helped make Athens the region's center for trade.

Athens’s large juries were a subject of mockery by critics and even in the city-state’s famous literature (juries sometimes numbered the full assembly). But modern scholarship describes the Athenian system as working efficiently (most juries had a more manageable number). Citizens jealously safeguarded its basic features: a jury of one’s peers, equal access to courts and peaceful resolution of disputes.

Roman Law

The legal system of the Roman Republic, which evolved from the sixth to first centuries BCE, is another important tradition influencing current democracies. Roman law was less egalitarian than in Athens — a large purpose was to protect the wealth and property of aristocratic landholders.

Still, the Roman tradition implanted several legal principles. These include: the need for public knowledge of civil law and judicial procedures; the idea that law should be stable and evolve according to precedent and circumstances; and that natural law (universal rights that all persons are born with) may provide the basis for positive (or human-made) law. Although hardly fairly applied with the fall of the Republic, the Roman law tradition was maintained under both the Roman and Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empires and incorporated in some form into European law and practice through the Holy Roman Empire of the Middle Ages and Renaissance Era.

The Anglo-Saxon Tradition

The Magna Carta Libertatum (the Great Charter of Liberties) signed in 1215 CE by King John of England went further. It established the principle that the head of state had limited power in relation to the king’s subjects, whose interests must be represented in a deliberative body like a parliament as well as in independent courts (see also "The Magna Carta" in History in Constitutional Limits).

The Magna Carta established foundational limits of monarchy in regards to specific rules of law, introducing principles such as Habeus Corpus, due process and a jury of peers. The Magna Carta states:

No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any other way, nor will we [the King] proceed with force against him, or send others to do so, except by the lawful judgment of his equals or by the law of the land (emphasis added).

The Magna Carta established foundational limits of monarchy in regard to specific rules of law, introducing principles such as Habeus Corpus, due process and a jury of peers.

More than four hundred years later, in the mid-to-late 17th century, the disputes between parliament and the Stuart Kings of England led to further codification of these and other principles in law. The Petition of Right (adopted in 1628) more firmly grounded the rights of all citizens to petition government and to seek redress for abuses of power. It also barred the monarch from arbitrarily violating basic civil liberties or raising taxes without parliament’s approval.

The Habeas Corpus Act in 1679 formalized and strengthened the legal authority of the courts and the principle that anyone arrested by the king’s authority had the right to be presented on request to a judge to determine if there was legitimate cause for arrest so that people were not held in secret or arbitrarily. The law ordered "all sheriffs, jailers, and other officers" holding citizens in custody to "yield authority" to all writs of the court. (A Writ of Habeus Corpus, that is an order to bring forth a prisoner, came to be known also as the “Great Writ.”)

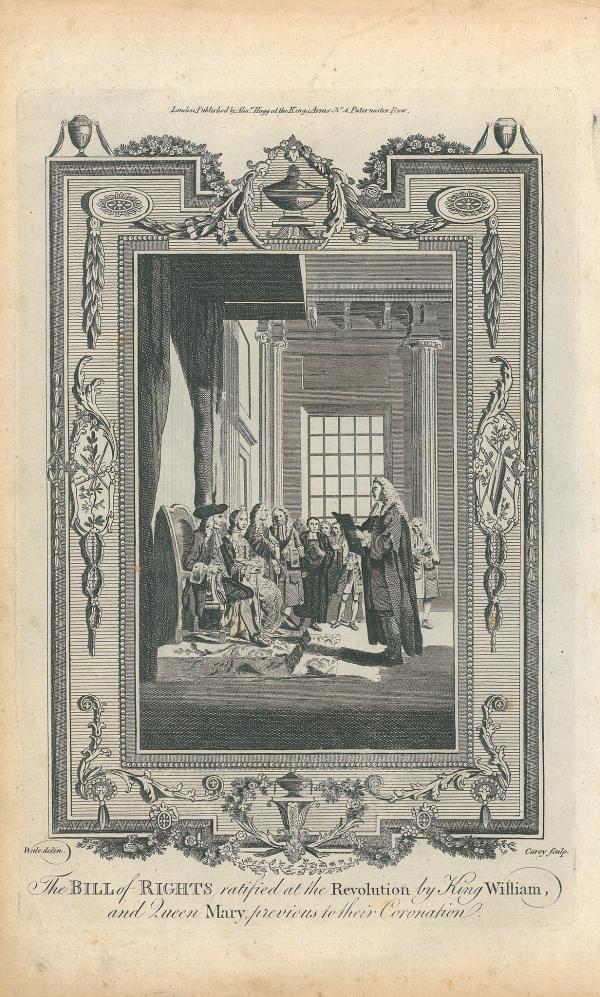

The Glorious Revolution of 1688 placed Protestants William of Orange and Mary on the throne in place of Mary’s father, the Catholic King James II. In doing so, parliament required that the joint monarchs accept a newly adopted English Bill of Rights. The Bill restated these two principles and formalized other foundations in the Anglo-Saxon tradition, including the right to trial by jury and the prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment.

A Bulwark Against Government Tyranny

The English Bill of Rights recognized the importance of human rights in natural law, a concept asserted by Enlightenment thinkers. Rights refer to an obligation that is owed a citizen by government [or] that must not be interfered with by government.

The English Bill of Rights recognized the importance of human rights in natural law, a concept asserted by Enlightenment thinkers. Rights refer to an obligation that is owed a citizen by government (such as due process and protection of property), as well as rights that must not be interfered with by government (such as speech or assembly).

According to Enlightenment philosophers, these are inalienable rights provided by a natural law, meaning they exist by birthright and are universal. All persons are entitled to them and a state may not violate them. Such rights became an indispensable part of representative government and adopted in both the American and French Revolutions and then more generally.

Natural rights should be protected by common law (law as determined by tradition or practice) and by positive law (law as determined by human-made statutes). Protections come in the form of constitutions, legislation and judicial decisions and precedent.

An engraving by Samuel Wale showing the English Bill of Rights being presented to William III and Mary II following the Glorious Revolution. Public Domain. National Portrait Gallery, London.

For example, the American Bill of Rights (in the fourth through eighth amendments) incorporated and extended British constitutional and common law protections of due process. These included protection against unwarranted search and seizures, the right to a fair and speedy trial, the rights not to incriminate oneself and to confront one's accuser in court, and protection against double jeopardy and cruel and unusual punishment.

In the US Constitution, these due process standards have been considered a bulwark against any threat of tyranny by the government. Even if not always adhered to, they became general principles and practices adopted by most democracies. Of course, the full respect for human rights to include all persons — regardless of race, gender, sexual orientation, religion, ethnicity or even property-owning status — required great struggle over the 19th and 20th centuries and continues in the current century.

The Separation of Powers

In modern democracies, the rule of law also evolved through development of a judicial system acting independently of executive and legislative branches. This meant judges making authoritative decisions on the basis of positive law and precedent. Baron de Montesquieu argued for such a separation of powers in The Spirit of Laws in 1748:

[T]here is no liberty if the power of judging be not separated from the legislative and executive powers. Were it joined with the legislative, the life and liberty of the subject would be exposed to arbitrary control, for the judge would then be the legislator. Were it joined to the executive power, the judge might behave with all the violence of an oppressor.

In modern democracies, the rule of law also evolved through development of a judicial system acting independently of executive and legislative branches.

The independence of the federal judiciary in the United States is established through Article 3 of the Constitution. Independence is ensured by the "advise and consent" powers of the Senate in approving a president’s nominees for federal judges and by the House and Senate's authority to impeach and remove judges from lifetime appointments for reasons of malfeasance.

In this way, the members of the judiciary are not controlled by arbitrary appointment or dismissal by the executive but may still be held accountable by an impeachment process. In other systems, accountability and independence is maintained also through term limits and mandatory retirement.

The Expansion of Rule of Law

The principles of rule of law and separation of powers in British, US and European constitutions had a great influence over the next two centuries. Its basic principles would expand globally through the British Empire, the Napoleonic wars after the French Revolution, the Wars of Independence in the Western Hemisphere, and the growing influence of the United States as a world power.

Rule of law principles came to symbolize the expansion of rights and liberties, including in British, French and other colonies. There, resident populations often sought justice and recognition of rights through colonial courts. Natural law arguments in favor of human rights, due process and self-governance became the basis for civic resistance among independence and democracy movements worldwide.

Mahatma Gandhi is among the most known and most successful leaders who combined principles of non-violence with the struggle for human rights and independence. Above, Ghandi leads an independence demonstration in India prior to 1948. Public Domain.

The Indian leader Mahatma Gandhi is the most known and most successful of the advocates for combining principles of non-violent resistance against unjust laws (satyagraha) with the struggle for human rights and independence. Through mass civic resistance and the power of legal precedents, Gandhi forced the British government to abide by rule of law principles and ultimately accede to India’s independence. This strategy attracted many followers in Africa and Asia as decolonization gained momentum in the post-World War II period.

In the United States, its Supreme Court arbitrarily overrode Reconstruction amendments to the Constitution guaranteeing equal citizenship and voting rights. African American activists struggled for the next 80 years to restore those rights through rule of law principles aimed at reversing the Court’s earlier decisions. Among the campaigns was the Double V for Victory campaign during World War II (“Victory Against Aggression, Slavery and Tyranny” both abroad and at home). In the post-war period, Black followers of Gandhi, such as Bayard Rustin and Martin Luther King Jr., used mass protest and principles of non-violent resistance to empower African Americans to overthrow Jim Crow segregation and discrimination (see also Essential Principles for a fuller discussion of development of rule of law in the United States).

The Contraction of Rule of Law

Throughout history, tyranny stood in opposition to the rule of law. Tyrants ruled arbitrarily — without checks or balances on their rule. The lack of separation of powers in government usually had severe consequences. The institutions of law and order became state instruments of oppression. In a popular reaction to absolute monarchy and arbitrary rule, citizens across Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries engaged in revolution or mass protest to limit monarchies through constitutions or to overthrow monarchies and to establish republics (see also History in Constitutional Limits).

Throughout history, tyranny stood in opposition to the rule of law. Tyrants ruled arbitrarily without checks or balances on their rule. The lack of separation of powers in government usually had severe consequences.

Dictators in the 20th century recognized the power of law as a foundation for governance and developed false claims to “rule of law.” Nazi Germany and other Fascist states imposed new legal systems based on the supreme power of the leader. Communist regimes superimposed the class struggle over "bourgeois" concepts of human rights for attaining a classless egalitarian society. Constitutions in communist countries often stated guarantees for basic human rights but then established the absolute authority of the Communist Party to decide all aspects of law and life. In practice, this meant imposing a new class system based on communist party membership. In both fascist and communist regimes, absolute power concentrated in the ruler or ruling party meant courts were simply instruments of state repression.

Some Western intellectuals were seduced by the idea of a higher form of justice or morality based on nationalist, race-supremacist or socialist law and supported fascist and communist regimes. But there was no law as such. There was only legalistic justifications for the most brutal actions: mass murder, forced labor, ethnic cleansing and genocide.

The Italian fascist leader Benito Mussolini and German Nazi leader Adolf Hitler both abused the concept of “law” to impose new legal systems based solely on the supreme power of the leader. They are shown here in June 1940 in Munich. Public Domain.

Universality of Rule of Law

A significant effort to establish universality of natural law were the abolition movements of the United States and Great Britain. As a result of public pressure and moral suasion, the British Parliament in 1807 passed the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act. This law empowered the Royal Navy of the British Empire to intercede ships and to act to end the slave trade on the African coasts. (The Royal Navy interceded 1,600 ships and freed 150,000 slaves between 1808 and 1860.)

In the United States, the abolition movement was the political force that succeeded finally in ending slavery and establishing equal rights of Black citizens through the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments following the Civil War. As a matter of international law, the Slavery Convention of 1926 was among the first international treaties to establish universal rights (it was updated in a Supplementary Convention in 1957).

The struggle against fascism and Nazi Germany in World War II made urgent the need to establish universal standards of human rights and the rule of law. A precedent was set in the Nuremberg and Tokyo War Crimes Trials in establishing individuals carrying out aggression, war crimes and crimes against humanity on behalf of governments accountable for their actions. More importantly, international treaties such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), the Convention Against Genocide (1948), the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966), and the Convention Against Torture (1984), among others have established a broad array of universal human rights standards (see Resources and also Human Rights).

Russian physicist Yuri Orlov (left) started the Moscow Helsinki Group to monitor compliance with the human rights provisions in the Helsinki Final Act in May 1976 at the home of Andrei Sakharov (shown right) with 10 other dissidents. It was part of a region-wide effort to push for rule of law in Soviet Bloc countries. Creative Commons. Photo of Yuri Orlov by Rob Croes for Anefo.

Universality of Rule of Law in Practice

Indeed, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was one of the bases of the German Constitution, which made it a state responsibility to uphold all human dignity in its first article (see quote above and Country Study of Germany in this section).

As noted in Essential Principles, rule of law principles were utilized successfully in the 1950s and 1960s in the struggle for decolonization as well as in the struggle against legalized discrimination in the United States. These principles were enhanced by the strengthening of international law and its application in the UN Commission on Human Rights (now the UN Council on Human Rights).

[R]ule of law principles were utilized successfully in the 1950s and 1960s in the struggle for decolonization as well as in the struggle against legalized discrimination in the United States.

Separately, the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe, which included member states of NATO and the Warsaw Pact, adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights within a security treaty called the Helsinki Final Act. While the Final Act’s main features were to establish mechanisms to maintain security between the two Cold War blocs without war breaking out, the treaty’s human rights provisions became the basis for organizing Helsinki Watch groups within the Soviet Bloc countries. These helped build both domestic and international pressure for adherence to human rights and became the basis for negotiating releases of dissidents and demanding democratic change in communist countries (see Resources).

Universal principles of Rule of law were re-enforced by the collapse of communism and the Soviet Union in 1989–91, by the end of apartheid in South Africa in the early 1990s, and by the collapse of military and fascist regimes in Latin America in the 1980s and 1990s.

On the other hand, the genocides in former Yugoslavia, Rwanda and other countries in the 1990s and 2000s showed that lawlessness remained prevalent in the world. These cases were the basis for establishing an international court system, including the International Criminal Court, to prosecute crimes against humanity and war crimes (see also Essential Principles in this section and Accountability and Transparency.) How effective these institutions are in deterring violations of international law remains a large question.

Religious Law and Its Abuse

Religious law is applied by the institutions within individual religions, usually by authorized religious clerics or officials. Countries where state religions were adopted (a common practice as nation states emerged) often incorporated strict interpretations of religious law within their court systems.

In the wake of bloody religious conflicts in Europe over centuries, Enlightenment thinkers argued that religion should be separate from the state’s application of the rule of law. That principle was incorporated in both the American and French Revolutions. Separation of church and state became a common principle for pluralist societies as democracy spread in the 19th and 20th centuries in Europe and the Western Hemisphere.

In the wake of bloody religious conflicts in Europe over centuries, Enlightenment thinkers argued that religion should be separate from the state’s application of the rule of law.

Although many democracies recognize a state religion, and may adopt laws approximating religious doctrine, religious law is generally not applied in court systems in democracies. The trend is towards liberalizing law from religious doctrines (as in the case of abortion recently in Mexico and Ireland).

In countries with dominant Muslim populations, Islamic or Shari’a courts are complementary and sometimes superior to state courts, especially in civil and religious matters (see, for example, Country Study of Malaysia). Depending on the school of Islamic justice, the rules and institutions vary. Some schools approximate Western rule of law principles (such as the use of precedent, stability of the law and equal application of the law).

However, theocratic systems were adopted in countries such as Iran, Afghanistan under the Taliban, Saudi Arabia and Sudan under the rule of Omar al-Bashir (see Country Studies). The quote of the Saudi constitution at the beginning of this section is representative of such systems. No separation of church or state exists and Islamic law and courts serve as instruments of harsh state dictatorship.

As well, in recent decades, fanatical movements such as al-Qaeda, Boko Haram, ISIS and Hamas have arisen to try to impose a fundamentalist vision of Islam through violence. In this vision, violence against Muslims and non-Muslims alike is justified to fulfill Islamist goals of creating a religious state or caliphate. These views have gained strong followings in northern Africa and the Middle East challenging the stability of many states (see, for example, the Country Study of Nigeria). But the beliefs of such movements are antithetical to the practice of Islam for most Muslims.

Current Trends

The rule of law, while under constant test, remains an essential principle for all democracies and is relied on to hold leaders and institutions accountable as well as to ensure transparency of government and thwart democratic “backsliding” (see below). Rule of law principles are also essential to combat corruption, prevent abuse of power, challenge wrongful convictions and hold police accountable for abuse.

Yet, Freedom House has recorded eighteen straight years of declines in its overall scores in its annual Freedom in the World survey. In many cases, declines in scores are steepest in rule of law categories.

Authoritarian, or “not free,” regimes have maintained or heightened repression and lawlessness. This is the case in the People’s Republic of China, Cuba, the Russian Federation and Syria, among others.

The rule of law, while under constant test, remains an essential principle for all democracies and is relied on to hold leaders and institutions accountable as well as to ensure transparency of government and thwart democratic “backsliding”

In some previously democratic countries, like Hungary, Turkey and Venezuela, leaders adopted a common pattern. They gained dominant control over legislatures through elections. The legislatures were then directed to adopt laws eliminating checks on the leaders’ personalized rule. The legislation included using the judiciary to render future elections unfree and unfair. The leaders installed personal and party loyalists as judges who would willingly act to violate precedent and constitutional principles to imprison opponents, excuse official misconduct, favor party supporters in business and skew electoral rules.

There also has been “backsliding” among many democracies. Israel, Poland and the United States are “free” countries that recorded declines of 9 to 12 points in their scores (see Country Studies). Their overall declines were due in part to drops in rule of law categories.

For example, in the United States, Freedom House cited police misconduct, mass imprisonment, wrongful convictions, racial profiling and Supreme Court rulings infringing voting and reproductive rights as factors in lowering scores in rule of law categories. In Israel and Poland, ruling parties sought to establish dominant control over judicial appointments and dismissals.

In each of the cases, rule of law principles as well as other essential principles of democracy (such as free elections, expression and association) have been drawn upon by the citizenry to organize mass protests and to try to protect or restore judicial independence and rule of law. In Israel, mass demonstrations over the course of 2023 protested so-called “judicial reform” laws, delaying their enactment. In Poland, a coalition of opposition parties defeated the entrenched Law and Order party in October 2023.

The content on this page was last updated on .