Summary

The United States is a constitutional republic with a presidential system. It is the world's oldest representative democracy among nation states. Governments have been elected under its constitution continuously since 1788-89. Today, however, the U.S. is a “backsliding democracy.” In the last decade, Freedom House’s annual survey reduced its overall rating from 92 to 83 (out of 100), among the steepest declines in countries designated “free” (see Current Issues).

The United States is a constitutional republic with a presidential system. It is the world's oldest representative democracy among nation states. Governments have been elected under its constitution continuously since 1788-89.

America’s democratic tradition dates to British settlements in the 17th century established on principles of consent of the governed. Elected representative assemblies emerged but self-governance was limited by governors appointed by the Crown, decrees of the British monarch and laws of the British parliament. These limits led colonists to demand greater autonomy and to organize the First and Second Continental Congresses made up of elected representatives of the thirteen colonies. On July 4, 1776, the Second Congress declared the colonies free and independent states that together formed the United States of America.

America's governance structure, adopted in a Constitution enacted in 1788, has constitutional limits. These include: separation of powers among the executive, legislative and judicial branches of government; checks and balances on each branch; and a federal system delegating non-federal powers to the states. In the Constitution and federal laws, there are also guarantees for free elections, majority rule and minority rights, accountability and transparency, economic freedom, rule of law and human rights (including free expression, free association and freedom of religion). There is vibrant civic participation and a multiparty system.

The Civil Rights Movement used principles of non-violence and civil disobedience to overcome legal discrimination and fulfill principles of the US Constitution. Its achievements are recognized worldwide as an example of democratic achievement. Above, A. Philip Randolph (center) leads the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Public Domain.

While founded on essential principles of democracy, the United States has enduring paradoxes. A government formed on the basis of liberty had largescale practice of slavery, which was introduced in the colonial period through the mass importation of Africans but only abolished through a bloody civil war in 1861–65. The United States also engaged in displacement and acts of genocide of Native Americans, the indigenous population, as part of continuous expansion. Despite constitutional amendments adopted to end discrimination against Black Americans and other minorities, slavery’s legacy continued for another century in the form of institutionalized segregation and discrimination.

While founded on essential principles of democracy, the United States has enduring paradoxes. A government formed on the basis of liberty had largescale practice of slavery, . . . [and] also engaged in displacement and acts of genocide of Native Americans.

Achieving a full democracy took long struggle. Women achieved the franchise only in 1919. Native Americans gained legal rights of citizenship in 1924 — although still facing discrimination and violations of their sovereignty. For Black Americans, it took until the 1950s and 1960s to achieve full citizenship and voting rights. The Civil Rights Movement, which used principles of non-violence and civil disobedience to overcome state-sanctioned violence and legal discrimination, is considered an example worldwide of positive democratic change. But continuing stark disparities in social and economic status reflect the difficulty of overcoming entrenched systems of injustice even in democracies (see also subsections in Free Elections and Majority Rule, Minority Rights).

Recently, the United States has faced serious challenges to its democracy. There is a weakening of democratic institutions as a result of extreme partisanship, the rise of oligarchic power and deliberate efforts to undermine constitutional norms and laws by a major political party (see also Current Issues).

America’s origins are rooted in struggles for religious freedom. Religious missionary movements also played a large role in the country’s expansion. The United States today still remains one of the more religious countries among the developed countries. Recent surveys of the Pew Forum for Religion and Public Life, however, show that Americans are becoming less religious (see link in Resources). As of 2023-24, twenty-nine percent (up from 16 percent in 2007) identify as “nones” (atheists, agnostics or unaffiliated to any religion), while sixty-five percent (down from 78.4 percent) identify as Christian (Protestant, Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox or Mormon). Judaism (1.7 percent) and Islam, Buddhism and Hinduism (each 1 percent), among other smaller faiths, account for six percent.

America’s origins are rooted in struggles for religious freedom. Religious missionary movements also played a large role in the country’s expansion. The United States today still remains one of the more religious countries among the developed countries.

From the original thirteen states, the country expanded westward after Britain ceded the Northwest Territories (land west of the Appalachians) in the 1783 Treaty of Paris. The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 extended US territory to the Pacific Northwest. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 ending the Mexican-American War set the country’s final contiguous boundaries from Atlantic to Pacific Oceans. As settlers moved across the continent, Native Americans were displaced and forced onto territory called reservations but which constitute 573 federally recognized tribal nations.

The US’s 48 contiguous states are bordered by Canada to the north and Mexico to the south. Two non-contiguous territories became states in 1959: Alaska, north of Canada’s British Columbia province, which had been purchased from Russia in 1867, and Hawaii, an island chain in the Pacific, which was annexed in 1898. US territory includes five inhabited self-governing island territories (American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico and US Virgin Islands); eight uninhabited territories; and Guantanamo Bay in Cuba.

The US is the third largest country in the world in territory (after Russia and Canada) and the third most populous (after China and India) at 340 million people (2024 US Census Office estimate). The US has the world’s highest nominal gross domestic product (GDP), projected by the International Monetary Fund to be $30.3 trillion in 2025. (The second highest is China at $19.5 trillion.) GDP per capita in 2024 was $86,601, sixth highest in the world.

History

The Colonies as Religious Refuge

Several of America's original English colonies were established as refuges for religious dissidents. The first were the 102 survivors of the Mayflower voyage, known as Pilgrims, who established the Plymouth Colony in 1620. The group was made up of “separatists,” a faction of the larger Puritan movement that refused to recognize the Church of England because it would not abandon Roman Catholic rituals, influences and structure.

Several of America's original English colonies were established as refuges for religious dissidents. The first were the 102 survivors of the Mayflower voyage, known as Pilgrims, who established the Plymouth Colony in 1620.

Less doctrinal Puritans took the same voyage to establish the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The two groups unified theological positions in 1648 as Congregationalists, so called because of the belief in the autonomy of voluntarily formed congregations.

As England's colonies in the New World expanded, many religious groups sought similar refuge to practice their beliefs free from the persecution and social ostracism they experienced in Europe. These included Protestant sects from various countries, including Anabaptists, Presbyterians, the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), as well as Catholics and Jews.

The Origins of Religious Freedom as a Principle of Governance

Some groups were as intolerant of others as their persecutors had been of them. The Puritans of the Massachusetts Bay Colony began as a formal theocracy. They were not the only ones to insist on conformity. At the time of the country's founding, nine of the 13 states had official religions and laws restricting or discriminating against other religious observance.

The Mayflower Compact, commemorted in a postage stamp above, was the first agreement to establish a civil government in the Americas. Unlike the Pennsylvania Framework of Government, it was explicitly theocratic. Public Domain.

Pennsylvania took a different path. Pennsylvania’s Frame of Government (1682) declared: “[Citizens] shall in no ways be molested or prejudiced for their religious persuasion or practice . . . nor shall they be compelled, at any time, to frequent or maintain any religious worship, place or ministry whatever.”

The Pennsylvania Frame of Government, largely written by William Penn, a Quaker leader, was an early landmark in the history of constitutionally protected religious freedom. Pennsylvania became a haven for many small European sects, including Amish, German Baptist groups, Confessors of the Glory of Christ, Dunkers, Mennonites, Moravians and Shakers.

Religious Belief and the Founding of the Republic

The American Revolution was motivated in part by a desire to protect the religious autonomy enjoyed by many communities against British control. Some advocates of the Revolution were millennialists who believed that defeating the “evil” British would bring about the second coming of Christ. Others, like the famous Boston preacher Jonathan Mayhew, asserted that it was a Christian's duty to oppose tyranny. The cleric Abraham Keteltas described the American Revolution starkly as “the cause of heaven against hell — of the kind Parent of the Universe against the prince of darkness and the destroyer of the human race.”

Article VI of the Constitution prohibits religious tests for federal office, while its First Amendment bans the establishment of an official religion and guarantees the free exercise of religious worship.

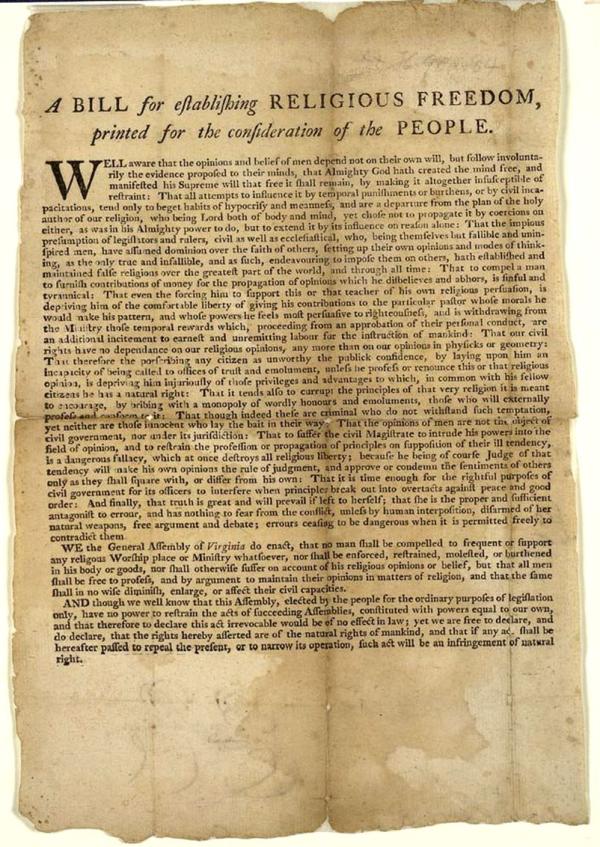

Thomas Jefferson, a non-denominational believer in Deism, considered such religiosity to be dangerous to the unity of the fledgling country. His own state, Virginia, imposed penalties, including death, for deviant religious observance, especially that of Quakers and Baptists. Jefferson thus drafted the Virginia Statute for Establishing Religious Freedom. Guided by another founder, James Madison, the statute was adopted in 1786 after Jefferson’s appointment as minister plenipotentiary to France.

Some Founders embraced the idea of adopting a national state religion, but Jefferson, Madison and other framers at the Constitutional Convention opposed adopting any uniformity of belief by a national government. They won the debate. As a result, Article VI of the Constitution prohibits religious tests for federal office, while its First Amendment bans the establishment of an official religion and guarantees the free exercise of religious worship.

“To Bigotry No Sanction” & A Wall of Separation

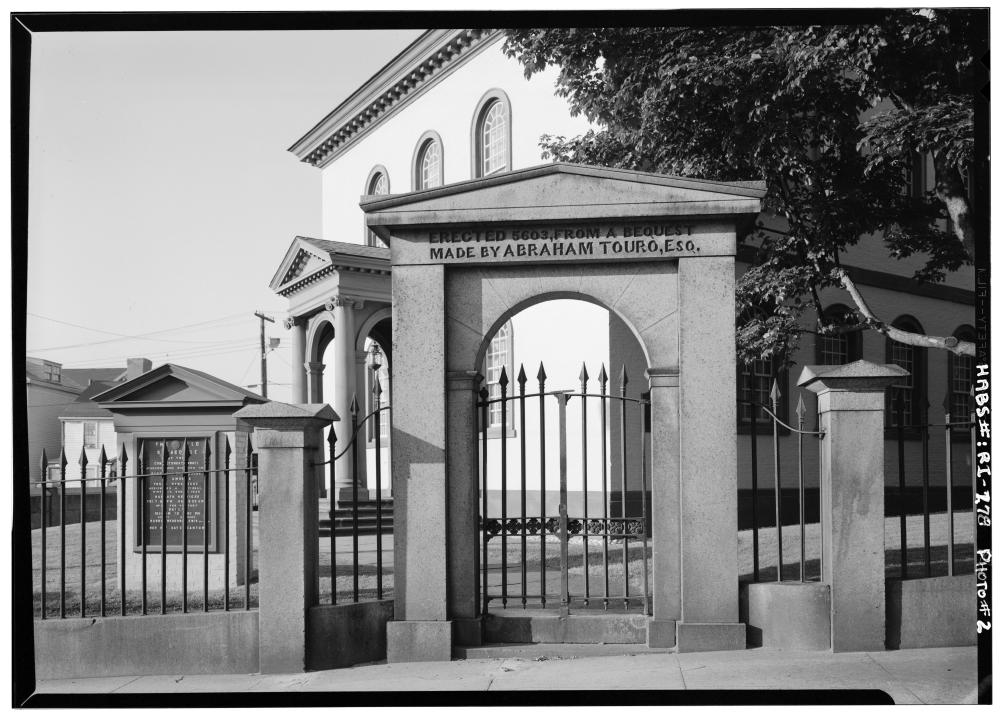

President George Washington and Vice President John Adams both believed in a role for religion in national life but became firm supporters of the separation of state and religion. George Washington’s views were famously stated in his pledge in 1790 to the Jewish congregation of the Touro Synagogue in Newport, Rhode Island. In regard to religion, Washington wrote, the new republic would give “to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance.” (The Touro Synagogue stands today, among the oldest active synagogues in the world.)

In 1790, George Washington wrote to the Jewish congregation of the Touro Synagogue in Newport, Rhode Island, built in 1763. The new republic, he wrote, would give “to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance.” Above, the entrance to Touro Synagogue, which stands today, in 1933. Public Domain.

Among the first treaties the US government signed was with the Muslim Barbary States in North Africa. The Treaty of Tripoli, which came into force in 1797, had as its principal aim to end acts of piracy threatening trans-Atlantic trade. It declared:

[T]he government of the United States is not in any sense founded on the Christian religion and it is declared by the parties that no pretext arising from religious opinions shall ever produce an interruption of the harmony existing between the two countries.

This provision in the treaty (Article 11) was a clear, early statement that the United States is a secular state. John Adams, president at the time, considered it necessary to demonstrate the neutral intentions of the US government toward predominantly Muslim nations.

Thomas Jefferson argued for a broader constitutional doctrine as the nation’s third president. In a letter to the Danbury Baptist Association in Connecticut in 1802, he wrote there should be “a wall of separation between church and state.” Supreme Court decisions on religious issues have often cited this phrase as the original intent of the First Amendment (see Freedom of Religion section below).

Religious Pluralism

In practice, the separation of religion and state meant a continued flourishing of religious beliefs, practices and institutions that functioned without state interference. A wide variety of religions and sects found a haven in territory stretching to the Pacific Ocean.

In practice, the separation of religion and state meant a continued flourishing of religious beliefs, practices and institutions that functioned without state interference. A wide variety of religions and sects found a haven in territory stretching to the Pacific Ocean. Most religious groups were Protestant. Mirroring colonial history, different missionary movements arose adopting a Christian nationalist view of the country (Congregationalist, Methodist, Baptist and others). These were central to developing and organizing settler communities. Another group, the Church of Latter Day Saints, pioneered a new state (Utah) after experiencing persecution in the East.

African Americans established their own denominations, including the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, Baptist and other congregations. This was due to major Protestant groups justifying slavery and discrimination in their religious doctrine and practice. These denominations remain the most widely practiced by Black Americans. Several denominations (Quakers, Unitarian-Universalists among others) also welcomed Black Americans. Since the Civil Rights Movement, these and mainline congregations have increased in Black membership.

Thomas Jefferson put forward the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom (above) in 1779. Adopted by the Virginia General Assembly in 1786, it introduced a framework for freedom of religion adopted in the US Constitution and First Amendment. Public Domain.

While most Americans practiced Protestant Christianity, Catholicism became more widely practiced starting in the mid-18th century due to immigration from predominantly Catholic regions and countries in Europe. Roman Catholicism has become the second most widely practiced faith. Eastern Orthodox Christianity has a smaller but significant presence through immigration from the Balkans and Russia. (Today, around twenty percent of Americans identify as Roman Catholic and two percent as Eastern Orthodox.)

Judaism became more widely practiced with immigration from Eastern Europe as Jews escaped pogroms in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and later escaped Nazi tyranny. Several branches (Orthodox, Conservative and Reform) are practiced. Today the United States has the largest diaspora population of Jews in the world (between 5.6 and 6.8 million).

Adherents of Islam, Hinduism and Buddhism, among other smaller faiths, have found a home in the United States and all have grown in number since 1965 due to adoption of a new immigration law.

Religious Discrimination

Separation of church and state did not mean an end to religious discrimination or persecution. There were many acts of violence and repression against religious groups in America’s history due to religious and racial intolerance by mainline denominations. There was also violence against Native Americans due to their indigenous faiths as well as of Black Americans. In the Jim Crow South, there was widespread bombing, burning and defacing of Black churches.

Separation of church and state did not mean an end to religious discrimination or persecution. There were many acts of violence and repression against religious groups in America’s history due to religious and racial intolerance by mainline denominations.

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, general bigotry and discrimination was also common for Jews, Muslims, Roman Catholics, non-traditional Protestant sects and practitioners of Asian religions (especially by Chinese immigrants), as well as for agnostics and atheists. Access to jobs, property, schools and higher education were restricted by informal as well as legalized discrimination. There were formal quotas adopted in institutions of higher education especially to limit the number of Jewish students.

Many legislative and court actions have been taken to try to eliminate discrimination based on religion. These are described below.

Freedom of Religion

As noted, the basic principles of freedom of religion in the United States are grounded in Article VI of the Constitution barring a religious test for federal office together with the First Amendment to the Constitution. It states:

Congress shall make no law respecting the establishment of religion or prohibiting the exercise thereof. . . .

Alexis de Tocqueville wrote in Democracy in America, “[A]ll citizens in the United States . . . believed religion to be indispensable to the maintenance of republican institutions.”

This was the most definitive statement regarding freedom of religion among nation states at the time and it established a new paradigm allowing full practice of many different religious faiths without state discrimination.

Religious institutions had more than a spiritual function in both colonial and US history. They served as organizing centers for developing communities and formed the bulk of social service organizations in America (see also Freedom of Association). This had political significance. As Alexis de Tocqueville wrote in Democracy in America, “[A]ll citizens in the United States . . . believed religion to be indispensable to the maintenance of republican institutions.”

For one, religiously based groups were a community bulwark capable of mobilizing citizens to act on their own behalf and on behalf of others. As well, they spearheaded many movements for change that expanded and fulfilled principles of democracy, including those for abolition, suffrage, labor rights and civil rights.

[T]he role of religion in American democracy has a complex history. Appeals to religion were common also to justify slavery and legalized discrimination. The supposed right of “Christian discovery” was used in Supreme Court rulings allowing displacement and genocide of Native Americans.

At the same time, the role of religion in American democracy has a complex history. Appeals to religion were common also to justify slavery and legalized discrimination. The supposed right of “Christian discovery” was used in Supreme Court rulings justifying displacement and genocide of Native Americans. Some counter arguments made in Congress and by Native American tribes against legislative approval of displacement were also based on religious principles, but these arguments lost.

This section does not examine all aspects of the issue of freedom of religion or its history in the U.S. but rather focuses on constitutional debates involving how freedom of religion was interpreted in practice. These debates formed the basis of national discussion and were generally decided in rulings of the Supreme Court, whose decisions are the law of the land. Those political debates are ongoing (see also Current Issues).

Freedom of Religion, the Constitution, and the Supreme Court

Early decisions of the Supreme Court interpreted the First Amendment's Establishment Clause as applying only to the federal government, which left individual states to choose whether to maintain official religions. In the end, all the states adopted the national principle of separation of church and state. States with official religions disestablished their respective churches. (Massachusetts was the last to do so in 1833.)

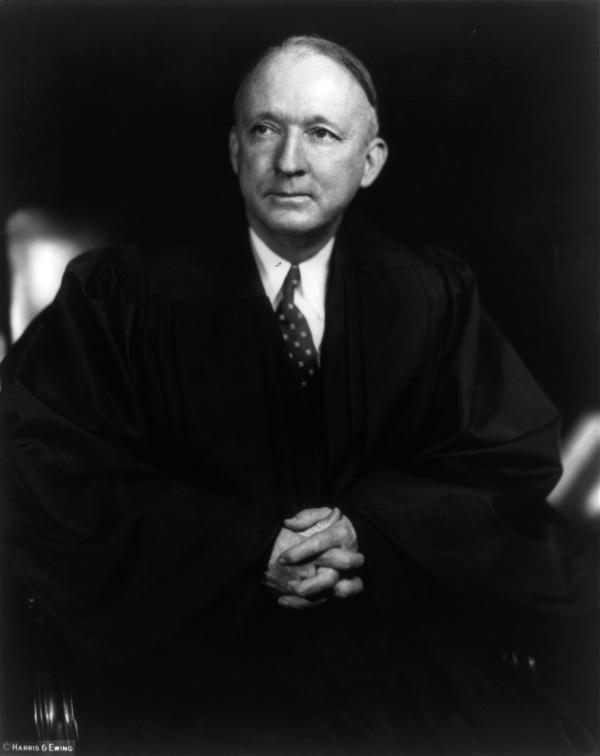

Justice Hugo Black defined the Supreme Court’s broad understanding of the First Amendment’s Establishment and Free Exercise Clauses in a 1947 case, Everson v. Board of Education. Shown above in 1937. Public Domain. Library of Congress.

The 14th Amendment to the Constitution, enacted soon after the Civil War, applied the protections of the Bill of Rights — including the Establishment and Free Exercise Clauses of the First Amendment — to the states. Still, many issues remained unclear, such as whether federal or state law superseded religious practice.

In an important precedent, Reynolds v. United States (1878), the Supreme Court upheld a federal law against polygamy despite a man's claims that the practice was a religious duty under the Church of Latter Day Saints. The Supreme Court (referring to Jefferson's letter to the Danbury Baptists) held that the Constitution barred Congress from interfering in “religious opinion,” but it was empowered to regulate “actions that were in violation of social duties or subversive of good order.” Reynolds v. United States remains a precedent for laws against polygamy and other practices seen as violating general norms set in secular law.

The Essential Principle in More Detail

One major Supreme Court decision, West Virginia State Board Of Education v. Barnette (1943), came to define principles of religious freedom and conscience, especially in relation to freedom of expression.

An earlier case, Minersville School District v. Gobitis (1940), ruled in favor of the school district, which had expelled two students from school for refusing to pledge allegiance to the US flag as required by state law. The children were Jehovah Witnesses, which considered a pledge to an object to be sacrilegious. Federal district and appellate courts ruled that the expulsion violated the students’ religious expression but the Supreme Court, citing Reynolds, rejected the lower courts’ rulings and upheld the state’s power to impose “political responsibilities.”

If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion, or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein.

Justice Robert Jackson, 1948

Just three years later, the Supreme Court reversed that decision in the 1943 Barnette case. It also involved two Jehovah Witness adherents expelled for not pledging allegiance. In a ground-breaking majority opinion, Justice Robert Jackson wrote: “If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion, or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein.” Legislatures and schools, therefore, could not force children to state the pledge of allegiance if it violated their conscience or religious belief.

Another case, Everson v. Board of Education of Ewing (1947), involved a New Jersey taxpayer's objection to public funds being used to reimburse the transportation of students to a private Catholic school. In a complex ruling, the Supreme Court upheld the practice in a 5-4 decision as furthering a legitimate state purpose (the education of all children). But all nine justices joined a sweeping opinion by Justice Hugo Black in which he defined the Supreme Court’s understanding of the First Amendment. He wrote:

The “establishment of religion” clause of the First Amendment means at least this: Neither a state nor the Federal Government can set up a church. Neither can pass laws which aid one religion, aid all religions, or prefer one religion over another. Neither can force nor influence a person to go to or to remain away from church against his will or force him to profess a belief or disbelief in any religion. No person can be punished for . . . professing religious beliefs or disbeliefs, [or] for church attendance or non-attendance. No tax . . . can be levied to support any religious activities or institutions. . . . Neither a state nor the Federal Government can, openly or secretly, participate in the affairs of religious organizations or groups and vice versa. In the words of Jefferson, the clause against establishment of religion by law was intended to erect “a wall of separation between church and State.”

Hugo Black’s 1947 ruling was the first time the Supreme Court had definitively applied the Establishment Clause to the states employing the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause. Future decisions, upholding the Barnette and Everson rulings, would end obligatory prayer and Bible reading in public schools (Engel v. Vitale, 1962) as well as any government payment of private school teachers' salaries (Lemon v. Kurtzman, 1971).

Plural Interpretations

Yet, the tension between the establishment clause and the free exercise clause continued to be at issue.

Justice Robert Jackson wrote that a “fixed star in our constitutional constellation” was that no government official could force children to Pledge Allegiance to the Flag if it violated their conscience. Above, Jackson argues a case as chief prosecutor at the 1945-46 Nuremberg Trials. Public Domain.

In Sherbert v. Verner (1963), for example, the free exercise of religion was re-affirmed. The Supreme Court held that a 7th-Day Adventist could not be denied unemployment compensation after being fired for refusing to work on Saturdays, which was prohibited by the employee’s religion. A new “Sherbert Test” stated that individuals should not be pressured to violate or alter the exercise of their religion by imposing a government penalty or withholding a government benefit except where a compelling state interest could be shown.

In 1990, however, the Supreme Court gave the original Reynolds standard renewed weight. In Employment Division v. Smith, the majority opinion upheld the state of Oregon’s right to dismiss employees for banned drug use in a case involving two members of the Native American Church fired when peyote was found in their blood system in a drug test. The employees stated peyote use was required by religious rituals. Justice Antonin Scalia ruled that the law was constitutional under the Sherbert Test since it did not aim to punish or prevent a specific religious practice but was neutrally based for all members of society.

Both religious liberty and civil liberty groups objected to the ruling. As a result of their lobbying, Congress passed the Restoration of Freedom of Religion Act (RFRA) in 1996 to create a statutory basis for preventing government from restricting specific religious practices. This made the free exercise “Sherbert Test” the stronger precedent in federal law than the Reynolds’s establishment clause standard. The Supreme Court later ruled, however, that the RFRA applies only to federal laws, and thus did not set a national constitutional standard for all states.

The boundaries of these precedents continued to be debated. On a single day in 2005, the Supreme Court handed down two decisions that interpreted the Sherbert Test in different ways. One determined that the display of the Ten Commandments in a Kentucky courthouse ordered by the chief judge was unconstitutional (McCreary County v. ACLU). The second upheld the constitutionality of another long-standing display of the Ten Commandments outside the Texas Capitol building (Van Orden v. Perry). The grounds were that the court officer was openly proscribing specific religious tenets while the monument did not have such an intent.

A Tilt Toward Religion

Other decisions tilted towards religious practice, adding to the debate over the meaning and scope of the Establishment and Free Exercise clauses.

Other decisions tilted towards religious practice, adding to the debate over the meaning and scope of the Free Exercise and Establishment clauses. In 2002, for example, the Supreme Court decided (by 5-4) that parents could use tuition vouchers for religious schools so long as they could choose among secular and religious schools (Zelman v. Simmons-Harris). In June 2014, the court decided that under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), private and for-profit corporations could not be forced to provide specific health care coverage if doing so violated religious beliefs (Burwell v. Hobby Lobby). In the case, the Hobby Lobby corporation objected to insurance coverage for contraception as required by the Affordable Care Act. The government argued that interpreting the RFRA in this way gave license to private groups not to obey federal laws on religious grounds (contrary to the long-standing Reynolds precedent).

Recent decisions have also expanded interpretation of the free exercise clause. In two cases (Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado EEOC and Creative Design v. Ellis), the Supreme Court held that private businesses could refuse service to LGBTQ+ individuals based on religious beliefs — notwithstanding protections for equal treatment of all citizens in the 14th Amendment and the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Another decision affirmed a state’s practice of offering vouchers for religious schools when a secular school is not available to parents (Carson v. Makin).

These and other Supreme Court decisions did not formally reverse precedent, but they are increasingly at odds with Hugo Black’s statement on the meaning of the Establishment Clause.

These and other Supreme Court decisions did not formally reverse precedent, but they are increasingly at odds with Hugo Black’s statement on the meaning of the Establishment Clause (see above). The recent decisions, made by a Republican-appointed majority, generally favor religious and conservative groups aligned with the Republican Party (see also below). Such groups seek ultimately to impose a religious foundation to the US Constitution — in contrast to the founders’ intent to separate state and religion. Towards this end, several state laws were passed in 2023-24 in the hope of fully reversing precedents prohibiting religious instruction, displays and prayer in public schools and more broadly allowing state vouchers for religious schools.

More generally, there is a rise of religious intolerance. After a period in which smaller religious faiths had witnessed a decline in hate crimes, there was a marked increase in such acts in recent years, especially those directed at Jews and Muslims. The number of anti-Semitic and anti-Muslim hate crimes escalated in 2023-24 partly in relation to protests regarding the Hamas attack on Israel on October 7 and the subsequent Israel-Hamas war.

Current Issues

In recent years, the United States has faced a number of challenges to its democracy. Recent elections saw increasing partisanship and broad shifts in both policy and governance that are testing America’s democratic institutions.

In recent years, the United States has faced a number of challenges to its democracy. Recent elections saw increasing partisanship and broad shifts in both policy and governance that are testing America’s democratic institutions.

As in Poland (see Current Issues in Country Study), American politics saw a marked political shift to the right in 2015-16 with the political rise of Donald Trump and his nomination as the Republican Party presidential candidate. A billionaire real-estate developer with no experience in elected office, Trump pledged to run the country “like a business.” He campaigned on a chauvinist platform that included expelling millions of migrants, building a 2,000 mile border wall and banning Muslims from entering the country. Trump narrowly won the presidential election in a race with Democrat Hillary Clinton based on the United States’ use of an Electoral College, rare in democracies, based on individual elections in each state. He lost the national popular vote by nearly 3 million votes or 2.1 percent of the vote (see also below).

In office, Trump violated democratic norms and broke through constitutional safeguards to carry out his policies. This was especially the case after Republicans lost the House of Representatives to the Democrats in 2018 mid-term elections. In one instance, the House of Representatives impeached the president for abuse of power and obstruction of Congress for improperly trying to aid his re-election. (Trump had withheld military aid appropriated by Congress to pressure the president of Ukraine, an ally at war with Russia, to announce a fake corruption investigation of Trump’s political opponent.) Due to party-line voting, the Senate did not convict Trump at trial by the necessary two-thirds majority (see also subsection in Accountability and Transparency).

As in Poland, American politics saw a political shift to the right in 2015-16 with the political rise of Donald Trump and his nomination as the Republican Party presidential candidate.

A more serious challenge to American democracy arose when Trump lost the 2020 presidential race to the Democratic Party candidate, Joseph Biden, who won by a large 7 million popular vote margin but by narrow margins in seven states deciding the Electoral College. When sixty-three federal and state courts rejected false claims of election irregularities, Trump tried to overturn the result by extra-constitutional means, including by inciting a violent assault on Congress by his supporters to halt the formal counting of Electoral College votes. The House of Representatives impeached Trump a second time on the charge of incitement of insurrection. A Senate trial again did not convict due to party-line voting (see also subsection in Consent of the Governed).

Biden had run for president on a pledge to reverse Trump’s immigration restrictions, strengthen democratic institutions and end forty years of what he termed “trickle-down economics” (see also subsection in Economic Freedom). With a slim Democratic majority in both chambers of Congress, Biden put in place major investment and redistributionist policies that helped keep employment levels at a record high. He did not gain wide support, however, due to a corresponding period of high inflation and large-scale migration. These issues, common worldwide after the pandemic, fueled anti-incumbent sentiment.

For the 2024 election, Trump was again the Republican Party (GOP) nominee for president despite a 34-count felony conviction by a local Manhattan court and despite federal and state indictments for attempting to overthrow the prior election, among other federal charges (see also subsection in Rule of Law). Trump continued to deny his election loss in 2020 and threatened again to refuse to accept the result if he lost. But after Biden withdrew from the race for age-related reasons, Trump defeated the Democratic Party’s new candidate, incumbent Vice President Kamala Harris, by narrow margins in both the Electoral College and national popular vote. The Republican Party won slim majorities in both chambers of Congress, giving it unified control of government. Harris and the Democratic Party accepted the election results.

The Supreme Court made a “paradigm shift” in the US Constitution by granting presidents immunity for prosecution for acts while in office in a case involving former president Donald Trump’s culpability in attempting to overturn the 2020 election, including inciting his supporters at a rally (shown above) to assault the Capitol on January 6, 2021 Shutterstock. Photo by: Philip Yabut.

During the campaign, Trump again made authoritarian-style pledges to remake America. These included: use of the military for domestic law enforcement; pardoning those convicted in the January 6 insurrection attempt; penalizing media for negative coverage; using the Department of Justice to seek retribution for political enemies; ending civil rights enforcement; ending birthright citizenship; and deporting at least 11 million immigrants, whom Trump falsely claimed to have fueled a crime wave. (Crime declined significantly in the period 2022-24 nationally and in most major urban areas.)

As in his first term, Trump has acted quickly to challenge democratic norms. Since being inaugurated on January 20, 2025, he signed Executive Orders that overstep constitutional limits and violate existing laws in order to carry out his campaign pledges. One orders the end birthright citizenship, which is guaranteed in the 14th Amendment to the Constitution. Other orders and a new agency for government efficiency headed by fellow billionaire Elon Musk have acted to arbitrarily close government agencies and end government contracts and programs. At present, many legal challenges have been made in courts to contest the orders.

Conditions in the United States mirror those in democracies experiencing a rise in far-right politics. . . . Among democracies, however, only Poland and Israel saw sharper drops in Freedom House ratings over the past decade, with the U.S.

Conditions in the United States mirror those in democracies experiencing a rise in far-right politics due to high levels of immigration (see Country Studies of France and Netherlands). Among democracies, however, only Poland and Israel saw sharper drops in Freedom House ratings over the past decade, with the U.S. falling 9 points (from 92 in 2014 to 83 out of 100 in 2024). General reasons for the decline include a rise in extreme partisanship, inequity in the justice system and growing economic disparity. During Donald Trump’s first presidency (2017-21) there were specific declines in scores due to his administration’s breaches of ethics, violations of immigrant rights, abuses of power and the violent attempt to prevent a peaceful transfer of power.

Democracy scholars point to several structural weaknesses in the US system to explain the democratic backsliding. One is use of an anti-majoritarian Electoral College to elect national officers instead of the popular vote, as used by other major democracies. The Electoral College superseded the national popular vote in two of the last seven presidential cycles, in 2000 and 2016, and generally distorts presidential election campaigns to focus on the few states with small vote margins that determine their outcome. Other structural weaknesses include:

• the anti-majoritarian composition and rules of the Senate;

• the lack of specified terms and mandatory retirement for high court judges (as exist in nearly all other democracies); and

• the lack of an affirmative or universal right to vote, with election rules being set at the state level.

Democracy scholars point to several structural weaknesses in the US system to explain the democratic backsliding. One is use of an anti-majoritarian Electoral College to elect national officers.

What makes these weaknesses more consequential in recent times are the adoption of anti-democratic practices by one of two major political parties, the GOP. Most significant are: the tolerance of political violence (including approval of Trump’s pardon of 1,500 criminals involved in the January 6, 2021 assault on Congress); a frequent refusal to accept election outcomes; and the adoption of state-level restrictions on voting and political gerrymandering of electoral districts. In many states controlled by the GOP, voter restrictions and gerrymandering are on a scale to neuter political competition and distort state and federal representation (see also subsection in Free Elections).

Due to the Electoral College and life-time appointments for justices, there has also arisen a political imbalance in the Supreme Court. While Democratic presidents held the presidency for five of the last eight terms, Republican presidents have appointed a 6-3 Supreme Court majority, including five justices named by presidents elected by non-majoritarian means.

According to democracy scholars, this single-party dominance of the high court has increasingly meant rulings favoring that party’s electoral standing and practices. These include decisions to allow unlimited financing of political campaigns (Citizens United v. FEC), voting restrictions that limit minority participation (Shelby v. Holder and Brnovich v. DNC), and partisan gerrymandering (Rucho v. Common Cause and Alexander v. South Carolina Conference of the NAACP). In the last four years generally, the Supreme Courts’ decisions have overruled federal laws, overturned or re-interpreted long-standing precedents, and made novel interpretations of the constitution. Such assertion of judicial power in accordance with one party’s political positions, together with reports of ethical violations by two Supreme Court justices, prompted calls for reform of the court, including for term limits and binding ethics requirements.

A dissenting justice called the [presidential immunity] decision a “paradigm shift” in the Constitution and the common understanding that “no person is above the law.”

In the view of many constitutional law experts, a more alarming partisan turn took place in 2024. Most important was the case of Donald Trump v. USA in which the former president sought the dismissal of his federal indictments by claiming “total” presidential immunity. The six Republican-appointed justices overturned District and Appellate Court rulings rejecting the claim. They ruled that there was presidential immunity for all official acts. The case was remanded back to the District Court for review on that basis, which meant no trial could be held before the 2024 election. A dissenting justice called the decision a “paradigm shift” in the Constitution and the common understanding that “no person is above the law.”

As a result of these decisions, it remains a question whether or not the Supreme Court will be a constitutional check on the broad executive powers now being asserted by Donald Trump in his second presidency (see above).

In addition to the above-cited weaknesses, the 2024 election re-enforced a general trend towards oligarchy in American politics. In the last forty-five years — a period when neo-liberal policies were dominant — $51 trillion dollars accrued to the country’s top 1 percent, while wages and wealth for workers remained mostly stagnant (see also Economic Freedom). This amassing of wealth is generally reflected in politics, with billionaires and large corporations funding political campaigns of both parties with the expectation of favorable policies.

In addition to the above-cited weaknesses, the 2024 election re-enforced a general trend towards oligarchy in American politics.

During the 2024 presidential campaign, Donald Trump especially sought contributions from fellow billionaires and large corporations by promising tax cuts, deregulation and the reversal of the anti-trust and pro-union policies adopted by the Biden Administration. After his election, Trump named 13 billionaires to advisory, ambassadorial and cabinet positions, including the world’s richest man, Elon Musk. Alone, he spent $250 million dollars to elect Trump. In return, he was put in charge of a government department to reduce federal spending with a large potential for conflict of interest given his own federal contracts.

Another concern of democracy experts is news media. There has been a large decline in local news outlets, while many parts of national print, broadcast and social media are now controlled by billionaires with economic interests in government policy. (This includes Musk, who owns the social media company X, formerly Twitter.) These outlets have often become vehicles for political propaganda and disinformation. Further, President Trump has acted to intimidate independent news outlets to align their coverage more favorably to him and his administration’s policies. This overall political distortion of media mirrors the “authoritarian capture” occurring in other backsliding democracies.

Despite its weaknesses, US democracy retains a number of strong elements as the country approaches the 250th anniversary of its Declaration of Independence.

While US political conditions mirror other countries, they also reflect the US’s history of chattel slavery and its periods of reaction to progress towards a multiracial democracy. Most notably, there was the ending of Reconstruction and the institution of Jim Crow segregation in the South, which ushered in a reign of violence against Black Americans to maintain white supremacism for a century after the abolition of slavery (see also subsection in Majority Rule, Minority Rights).

Despite its weaknesses, US democracy retains a number of strong elements as the country approaches the 250th anniversary of its Declaration of Independence. The Constitution’s separation of powers, federalism and limits on concentrated power still exist as potential guardrails to lawlessness (see subsection in Constitutional Limits). The judiciary as a whole has exhibited a general adherence to the rule of law. Notwithstanding serious challenges, free expression, free association and other basic liberties are exercised and America retains a vibrant civil society (see subsection in Freedom of Association). Most importantly, the country has an enduring legacy of free elections, electoral change and citizen mobilization that has overcome many prior challenges to America’s democracy.

The content on this page was last updated on .