Athenian Democracy and the Roman Republic

The concept of joining majority rule with minority rights was not central to ancient Athens or republican Rome. Certainly, minority groups were not protected. Both systems relied heavily on slavery, denied rights to women and foreign residents and repressed or acted against foreign religions, nations and even philosophical views.

Yet, majority rule did not reduce fully to majority or minority tyranny within either system. In Athens, political assemblies were governed by rules of debate that allowed both sides of a question to be addressed. Orators were judged less by rhetoric than by reason and appeals to common interest. Over decades, the Athenian assembly took decisions to defend the polis against attacks by foreign and domestic enemies. In that time, the majority did not act willfully but respected the law and the rights of the minority. As historian Donald Kagan wrote, “[It] would have been [simple] for the Athenian majority to plunder the rich and take revenge on their enemies.” The majority, he continued, showed a “combination of commitment and restraint necessary for the survival of popular government and life in a decent society.”

As historian Donald Kagan wrote, “[It] would have been simple for the Athenian majority to plunder the rich and take revenge on their enemies.” The majority showed a “combination of commitment and restraint necessary for the survival of popular government.”

Similarly, Republican Rome developed several means within its more complex constitutional structure for representing both majority and minority interests. The plebeians won representational rights for Tribunes not through mob action but through a single, disciplined act: withdrawing their labor. As in Athens, popular assemblies could have acted against the optimates, or the aristocratic class, which dominated the Senate. Cicero, Republican Rome’s great statesman, wrote, “[T]hough the people were free,” they respected that “no act of a popular assembly should be valid unless ordered by the Senate.” The people might be swayed by populist proposals (such as appropriating land for soldiers), but a popular majority did not adopt tyrannical behavior. Rather, a military takeover caused the breakdown of what Cicero called Rome’s “balanced constitution.”

Minority Rights in History

For most of history, the treatment of political dissenters, as well as of religious, racial or national minority groups, was mostly at the dispensation of autocrats. They ruled oppressively to safeguard their power or out of ingrained prejudice and racist beliefs.

For most of history, the treatment of political dissenters, as well as of religious, racial or national minority groups, was mostly at the dispensation of autocrats. They ruled oppressively to safeguard their power or out of ingrained prejudice and racist beliefs.

Among military empires, such as the Roman, Mongol, Ottoman, Russian and Spanish empires, the common practice was to dominate newly conquered populations through slavery or forced labor, other forms of labor exploitation and extraction of onerous payments of tribute. Often, they suppressed local languages, customs and beliefs and imposed their own as dominant.

A notable early exception, and a counter-example in history for many, was Cyrus II of Persia. The founder of the Achaemenid Empire, he issued the Cylinder of Cyrus upon conquering Babylon in 539 BCE. It proscribed religious tolerance and the right of national repatriation (including that of Jews held in captivity in Babylon). The cylinder is considered one of the first examples of adoption of minority rights.

Over millennia, Jews in captivity and in diaspora from the land of Israel were discriminated against as a religious as well as an ethnic minority. They had little protection from persecution or pogroms. In some cases, Jews were expelled outright, as from England and Spain in the 13th and 15th centuries, respectively. Even where Jews found places of refuge in Christian Europe, such as the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Austro-Hungarian empire, anti-Semitism was prevalent.

The Wars of Religion (1618-48) were among the bloodiest conflicts in world history. A collage of paintings depicting battles. Creative Commons License. Photos by David Dijkgraaf.

Within Christendom, persecution based on religion was widespread. During the Counter-Reformation, dominant Catholic rulers in Europe tried to suppress the rise of Protestantism. Wars of religion were waged culminating in the Thirty Years War (1618-48) ─ a conflict with a greater casualty rate than World War I. The Treaty of Westphalia ended the conflicts and established the principle of sovereignty and “Cuius regio, eius religio” (“whose realm, their religion”). Even then, many Protestants and Catholics in Europe (depending on whose realm they lived in) continued to be persecuted and sought refuge elsewhere, often in British colonies and then in the United States of America, where religious freedom was established as a basic right (see Country Study).

The Treaty of Westphalia ended the conflicts and established the principle of sovereignty and “Cuius regio, eius religio” (“whose realm, their religion”)

A key feature in the expansion of all European empires was the targeted killings, wars, displacement and other actions aimed at elimination, labor dominance or total separation of Indigenous nations and communities from colonists. It was only in the 20th century, mostly in democracies, that there arose greater respect for the rights of Indigenous nations and communities.

Discrimination and exploitation also happened within national groups. In India, for example, the caste system relegated Harijans, also known as Dalits or “untouchables,” to discrimination and conditions of terrible poverty. It is easy to find examples of persecution of targeted groups throughout the world.

Minority Rights in the Modern Era

While freedom of religion was foundational to the American Revolution, minority rights was not itself a foundational principle. The founders were mainly influenced by Enlightenment thinkers, who focused on individual rights (including freedom of conscience) as the basis for a social contract or covenant of citizens to the nation-state.

While freedom of religion was foundational to the American Revolution, minority rights was not itself a foundational principle.

In international law, minority rights in relation to religious, national and linguistic groups were introduced first at the Congress of Vienna, which ended the Napoleonic Wars. There, the major concern was protection of German Jews and national groups within the partitioned territories of the Poland-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

The term’s modern understanding was further established by the Paris Peace Conference of 1919-20 following World War I. The Treaty of Versailles and later the System of Minority Treaties specifically required respect for minority rights by members of the League of Nations with particular focus on the new independent nations being recognized in Central and Eastern Europe. These heterogeneous nations had emerged out of the defeat and break-up of the Central Powers (the Austro-Hungarian, German and Ottoman Empires plus Bulgaria) as well as the fall of the Russian Empire following the Russian Revolution of 1917. There was no mechanism of enforcement, however. As seen especially in the rise of fascist and communist regimes, the guarantees were not observed.

A Fundamental Paradox

"Ideas of human freedom and individual rights took root in nations that held other human beings in bondage and were then in the process of exterminating native populations." ─ Jamelle Bouie (2019).

Prior to that period, minority rights as a term related more to political factions within the context of the emergent democratic systems in the United States and Europe. With majority rule practiced as a principle, the rights of political minorities had to be considered (see also Essential Principles).

In an historic irony, one of the staunchest proponents of the rights of a political minority was John Calhoun, the 19th century US politician from South Carolina. As the country’s most significant proponent for slavery and the interests of slave states, he asserted the right of any individual state to act against actions by a majority of states. (He called his principle a “concurrent majority.”) This was the basis of the “nullification crisis” in the 1830s in which the federal government ultimately agreed to South Carolina’s demand to reduce national tariffs favored by the majority in northern states but rejected by southern states seeking to protect their exports based on enslaved labor. (South Carolina’s threat to secede at the time was thus withdrawn ─ only to be acted on in 1860.)

Calhoun’s assertions reveal a fundamental paradox of the Enlightenment. As the political theorist Jamelle Bouie has written,

Ideas of human freedom and individual rights took root in nations that held other human beings in bondage and were then in the process of exterminating native populations.

Even as “liberalism” claimed to expand economic and political freedom, Bouie continued, it created “racial constructs” for minority groups upon whom majority tyranny was imposed in the form of slavery and other forms of labor exploitation. This fundamental paradox had profound consequences.

Abolition and Minority Rights

At the same time, liberalism’s principles gave rise to history’s most significant political movement against majority tyranny.

In both Europe and other parts of the world, there were ongoing efforts to end both slavery and serfdom, Serfdom was another form of minority rule ─ debt peonage or indentured servitude that tied the majority of peasants to aristocratic property holders who held landed power within monarchical systems. Serfdom was gradually ended in Europe over the 18th and 19th centuries with the Industrial Revolution and the rise of liberalism. The largest action taken by any ruler was Alexander II’s abolishment of serfdom in Russia in 1861 in response to liberal demands among both intelligentsia and industrialists. This emancipated 23 million people from their legal servitude to landholders.

At the same time, liberalism’s principles gave rise to history’s most significant political movement against majority tyranny.

Abolition movements were related to but separate from efforts to end serfdom. They arose in opposition to the international slave trade and chattel slavery adopted in colonial holdings in the “New World” or Western Hemisphere by emerging European empires — first Portugal and then Spain, Great Britain, France and Netherlands.

Until then, slavery was generally time-limited and not inheritable, usually imposed as tribute or a means of absorbing more subjects within a conquering power’s population. Chattel slavery was a new form of servitude based on race that was life-long and inheritable. Adopted by white European imperial powers, the system of chattel slavery developed through the brutal oceanic transfer of purchased or stolen black Africans taken to the “New World” for enslaved labor to produce new labor-intensive crops such as sugar and tobacco. Current estimates are that 13 million people were forced to make the Atlantic voyage, with between 1 and 4 million killed in passage or on arrival. This system, instituted by colonial settlers on behalf of colonial empires, created an enduring “racial construct” to justify the brutalization of other humans based on skin color.

The most recognized movements to abolish slavery arose in Great Britain and the United States, two of the larger slave-holding nations. . . . Abolition activists pointed to slavery’s violation . . . of the freedoms, liberties and principles of equality found in their countries’ constitutional precepts.

The most recognized movements to abolish slavery arose in Great Britain and the United States, two of the larger slave-holding nations (the largest number of enslaved persons were held in the colonies of Portugal and Spain). Abolition activists in both countries pointed to slavery’s violation of basic humanity and of the freedoms, liberties and principles of equality found in their countries’ constitutional precepts.

Among empires, however, France was first to abolish slavery in its colonial territories. It did so first in its 1793 Constitution and second by act of the elected National Convention in 1794. Delegates acted largely in response to the slave revolt begun in 1791 on Saint Domingue, itself inspired by the French Revolution. It is the only instance of a successful rebellion in the Western Hemisphere against a slave regime. The free Black population later declared full independence as the Empire of Haiti in 1804 after having forced the military forces of Napoleon, who attempted to re-institute slavery after declaring himself Emperor, to withdraw from the territory.

The Somerset Precedent

Earlier, the British abolition movement achieved its own significant victory in a legal decision in 1772. The High Justice of the King’s Court, Lord Mansfield, issued a ruling in the case of Somerset v. Stewart declaring that slavery had no basis in English law. As a result, he freed James Somerset, who had escaped his enslaver when brought to England, from forcible recapture. After the Somerset ruling, slavery was treated by British courts as illegal within Great Britain. (This de jure freed around 15,000 persons enslaved mostly in domestic service.)

The Somerset precedent propelled further abolition efforts, led especially by an independent Member of Parliament, William Wilberforce. In 1807, prior to the United States, the British Parliament outlawed the international slave trade. In 1833, after decades of resistance by enslaved persons in colonies and citizen action in Britain, Parliament abolished slavery within the British empire. Within the decade, about 800,000 persons gained freedom on the Caribbean islands and in South Africa, although on the basis of compensation for slaveholders, not for the enslaved. (See also "The Evolution of Law" in Essential Principles in Rule of Law for further discussion of the Somerset precedent.)

An important example of the evolution and use of rule of law principles was the case of Somerset v. Stewart, which re-enforced principles of liberty established in the law. Above is a depiction of Granville Sharpe interceding with Charles Stewart, a slaver seeking to re-capture James Somerset. Somerset was freed on application for habeus corpus in a decision made by Lord Mansfield. Public Domain.

Abolition in the Western Hemisphere

The abolition movement in the United States, as in Great Britain, was initially propelled by the religious movement of Quakers in alliance with free Blacks. It achieved significant successes at first. These included: the gradual abolition of slavery in northern states beginning with Vermont in 1777; the adoption of the Northwest Ordinance in 1787 that banned slavery in most US-held territories won from the British in the American Revolution; and the constitutional provision outlawing of the international slave trade that took effect in 1808.

Emancipation for America’s four million enslaved persons was achieved only through the US Civil War and the victory of the United States against confederate states rebelling to preserve slavery

But these gains were negated by the continuing failure to secure equal citizenship rights for free Blacks in northern states; by the growth of the domestic slave trade; and by the large expansion of slavery to new states in territories outside the scope of the Northwest Ordinance, thereby increasing the national power of slave states.

The US abolition movement, based largely on Black resistance and the activism of white allies, reconstituted itself in the late 1820s and 1830s. But it only gained real influence in the 1850s through the rise of the Republican Party, which formed to protect the interests of “free labor” states and to prevent the expansion of slavery to new states. In the end, emancipation for America’s four million enslaved persons was achieved only through the US Civil War and the victory of the United States against confederate states rebelling to preserve slavery (see also "The African American Experience" below).

Latin America saw another significant, but long, effort to abolish slavery. Abolition was achieved at different times in different countries following their independence from the Spanish and Portuguese Empires. The first to abolish slavery was Chile in 1823; the last on the South American continent was Brazil in 1888; Cuba was last to do so in the Western Hemisphere in 1896. At the same time, nearly all countries in the Western Hemisphere retained systems of discrimination and labor exploitation for Indigenous populations and formerly enslaved persons (see, for example, Country Studies of Bolivia and Guatemala).

The African American Experience

In the United States, the African American experience is illustrative of the danger of systematic tyranny of a minority by a majority group.

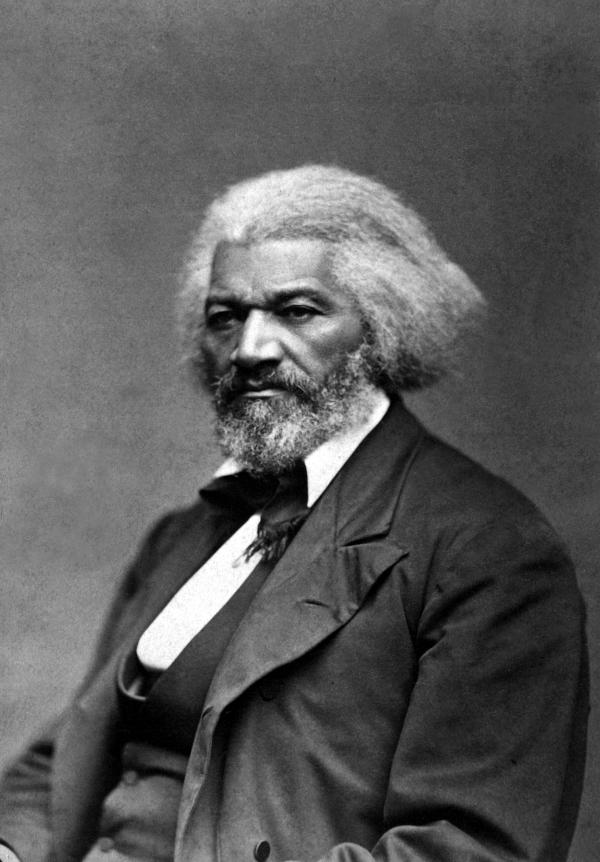

Frederick Douglass, a leader of the abolition movement and struggle for equal rights (shown above in a later photo dated 1878). Public Domain. National Archives and Records Administration.

The US Constitution, adopted in 1788, contradicted the founding principle of the Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal.” Slavery itself is not specifically mentioned. However, the Constitution’s provisions, including the continuation of the international slave trade for 20 years as well as a federal structure protecting “states’ rights,” ensured protection of slavery based on a racial caste system. The Constitution’s infamous “three-fifths clause” carefully avoided the word slave but served to enhance the political representation of slave states while denying rights to enslaved persons. This enhanced what was called the Slave Power, allowing this horrific system of subjugation to expand further to 15 of 30 states by 1845.

Guarantees of basic rights sometimes protected free Blacks in non-slave states, but these did not protect against their disenfranchisement. (In 1860, only five free states allowed Blacks the right to vote.) Worse, a specific clause gave rise to Fugitive Slave Acts in 1793 and 1850 that required northern states to recognize the rights of slave owners to hold “property in man” while in their territory and to return enslaved persons who escaped bondage to the North through legal claim in state courts. Free Blacks could also be abducted into slavery with no recourse in southern courts to regain their freedom. (As a result, many free Blacks escaped to Canada for safety.)

American democracy did not effectively address this system of majority tyranny until the Civil War. A first act was on January 1, 1863, when President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation as commander-in-chief, a military order declaring all enslaved persons within “states in rebellion” to be “henceforward and forever free.”

Abolitionists and Radical Republicans then forged a political majority to abolish slavery in all states in the Union through the 13th Amendment (ratified on December 6, 1865) and then to establish equal citizenship and voting rights in the U.S.’s foundational law through the 14th and 15th Amendments. These amendments (and Civil Rights and Enforcement Acts implementing them) were called the Second Founding and initially brought great advances for Black Americans during the Reconstruction period.

American democracy did not effectively address this system of majority tyranny until the Civil War. A first act was on January 1, 1863, when President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, a military order declaring all enslaved persons within “states in rebellion” to be “henceforward and forever free.”

Yet, these advances were short-lived after all former Confederate states were re-admitted to the United States. White dominance was re-established through organized violence, intimidation and continued control over property. A determined, racist Democratic Party recaptured state legislatures through voter intimidation and fraud. The “compromise of 1877” resolving a presidential election effectively ended Reconstruction in the South and resulted in re-imposition of full majority tyranny within the former confederate states.

In a series of rulings, the Supreme Court reversed the original intent of constitutional amendments to sanction a systematic regime of violence, labor exploitation and discrimination against Blacks and other minorities in southern and western states (see, e.g., “A Regional Reign of Terror” by Eric Foner in Resources). Other states adopted less systematic but still pervasive discrimination.

To overcome this new form of majority tyranny, political avenues were mostly closed to Black Americans. In the South the right to vote was denied. In the North, it was largely ineffectual in achieving political power. Another strategy was needed.

The Struggle Against Majority Tyranny

In 1905, W. E. B. Du Bois and other African American leaders formed the Niagara Movement, which in 1909 led to the establishment of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Other Black leaders organized for equal employment opportunities and treatment through trade union organizing and mobilizing citizens for mass action.

The stated strategy of all these initiatives was to use the freedoms enumerated in the Bill of Rights and Reconstruction amendments to challenge US institutions to live up to the country’s principles. Systematic denial of equality and justice was met with the persistent exercise of freedom.

The stated strategy of all these initiatives was to use the freedoms enumerated in the Bill of Rights and Reconstruction amendments to challenge US institutions to live up to the country’s principles. Systematic denial of equality and justice was met with the persistent exercise of freedom.

As with the abolition movement, success took decades.

The first mass African American trade union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, gained recognition and its first collective bargaining contract in 1937 after a twelve-year struggle. In the 1940s, the Brotherhoods’ leader, A. Philip Randolph, drew on the union’s strength to organize the March on Washington Movement (MOWW). Through its pressure, a federal executive order was issued in 1941 banning discrimination in defense industries and federal employment. With continued pressure organized by Randolph through the MOWM and other initiatives, an executive order was issued in 1948 barring segregation in the armed services. (The achievements were such that the numbers of the executive orders, Nos. 8802 and 9981 respectively, were common reference.)

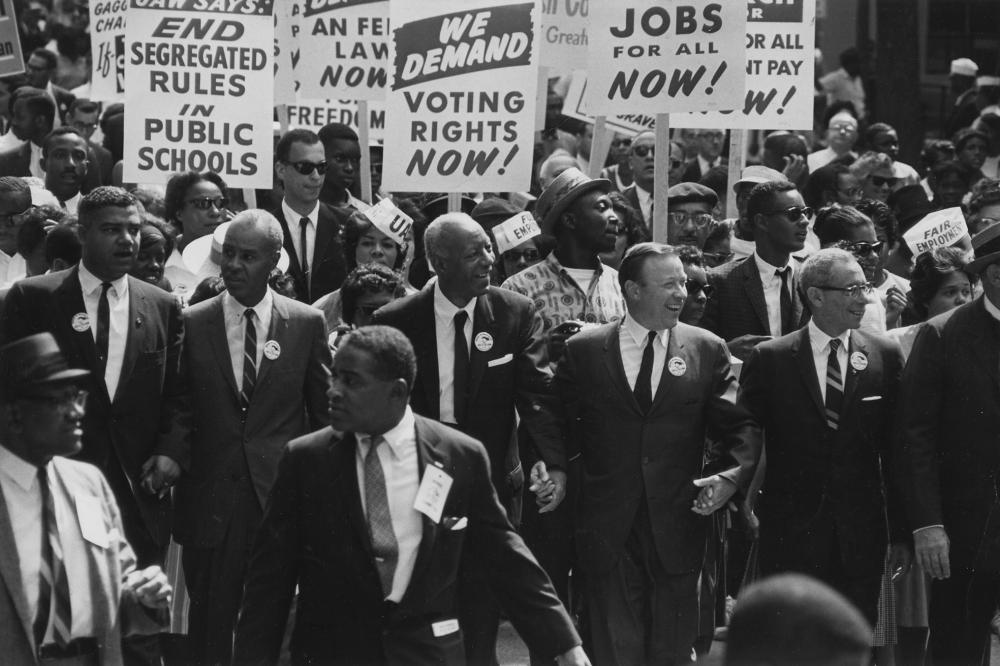

The Civil Rights Movement brought local, judicial, legislative and other victories that ended legal segregation and aimed to fulfill the original intent of the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments.

Through the NAACP and its Legal Defense and Education Fund, Charles Hamilton Houston, Thurgood Marshall, Constance Baker Motley and other lawyers achieved judicial victories at state and federal levels that reversed legal protections for segregation and discrimination. Most significantly, the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) formally overturned the “separate but equal” doctrine set in Plessy v. Ferguson nearly 60 years earlier that protected all segregation practices.

Larger success was found in the rise of the modern Civil Rights Movement, which was propelled by the 1955-56 Montgomery Bus Boycott, led by Martin Luther King, Jr. In the face of violent white resistance, the strategy of non-violence and mass protest adopted by Randolph, King and the Civil Rights Movement generally brought local, judicial, legislative and other victories that ended legal segregation and aimed to fulfill the original intent of the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments. These victories included: the 24th amendment to the Constitution banning poll taxes; the 1964 Civil Rights Act banning discrimination in public accommodations and employment; the Voting Rights Act of 1965; the Fair Housing Act of 1968; and affirmative practices to end workplace discrimination instituted by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

As in the 19th century with the struggle for abolition, support for equal rights was slow to build in the majority white electorate over the 20th century. But a large multiracial coalition registered approval for this fundamental change in policy in the landslide election victory in 1964 of President Lyndon Johnson, who had campaigned on a strong platform of civil rights.

The Civil Rights Movement used principles of non-violence and civil disobedience to overcome legal discrimination and fulfill principles of the US Constitution. Its achievements are recognized worldwide as an example of democratic achievement. Above, A. Philip Randolph (center) leads the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Public Domain.

Elusive Equality

Full equality remained elusive, not only for African Americans but for other minority groups, and especially Native Americans. The history of dispossession, forced relocations, slavery and institutional discrimination against minorities in America has led to widespread disparities in wealth and economic well-being. This remains a legacy of majority rule without minority rights. When addressing matters of social and economic equality, the large majority coalition that the Civil Rights Movement built to support legal equality weakened. Over time, there was a gradual reversal of precedents to address discrimination. (See, for example, "How a Civil Rights Idea Got Hijacked" by Nikole Hannah Jones in Resources.)

The history of dispossession, forced relocations, slavery and institutional discrimination against minorities in America has led to widespread disparities in wealth and economic well-being. This remains a legacy of majority rule without minority rights.

Yet, the methods adopted by Black organizations, their leaders and the Civil Rights Movement generally ─ A. Philip Randolph summarized the strategy as “pressure, pressure and more pressure” ─ led to significant accomplishments. They were the basis for gaining full majority support to embed minority rights as both a principle and practice of democratic governance and law in the United States. The American Civil Rights Movement became an enduring domestic and international symbol in the worldwide struggle for freedom and equality and a much-used model for how an oppressed group, whether minority or majority, can gain self-liberation through the determined and non-violent exercise of democratic rights.

The Ultimate Violation of Minority Rights

In the 20th- and 21st-centuries, the most extreme violations of minority rights and treatment of minorities have been found in dictatorships.

The Holocaust perpetrated by Nazi Germany murdered six million Jews, one-third of the total world Jewish population and two-thirds of European Jewry.

The worst examples are those of totalitarian regimes that carried out genocide to eradicate unwanted and targeted groups. The Holocaust perpetrated by Nazi Germany murdered six million Jews, one-third of the total world Jewish population and two-thirds of European Jewry. The Nazis also imprisoned and killed a large portion of the Roma community, homosexuals and other minority groups. The Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin, carried out mass executions and deportations of many nationalities, especially Caucasian and Central Asian ethnic and national groups. Stalin’s forced collectivization of agriculture led to widespread famine in many Soviet republics and the targeted killing of Ukrainians in the Holodomor (“death through famine”), resulting in three to five million deaths.

More recently, the Russian Federation waged a war against the republic of Chechnya, starting first in 1994-96 and resuming more brutally in 1999. Two hundred thousand civilians were killed and 400,000 of Chechnya’s 1.2 million people were forcibly displaced. The Russian Federation’s invasions of Ukraine in 2014 and 2022 have involved widespread torture, mass civilian killings, the destruction of Ukrainian communities, mass kidnapping of children and their forced relocation to Russia, and the systematic destruction of Ukrainian national culture in occuppied territories.

Stalin’s forced collectivization of agriculture led to widespread famine in many Soviet republics and the targeted killing of Ukrainians in the Holodomor (“death through famine”), resulting in three to five million deaths.

Other recent examples of genocide by dictatorships include the Nigerian government’s starvation campaign of Biafrans in the late 1960s (see Country Study); the Sudanese government's mass killing, raping and deportation of the Darfur minority (see Country Study in this section); and the mass imprisonment and destruction of the Uyghur and Tibetan communities (see "Suppression of Autonomous Regions" in The People's Republic of China Country Study); among too many others.

Slobodan Milosevic’s project to create an “ethnically pure” Greater Serbia in the 1990s resulted in the killings of more than 200,000 Bosnian Muslims and 10,000 Albanian Muslims in Kosovo. These “ethnic cleansing” campaigns were stopped only by NATO military intervention — one of the few effective international actions to protect minority groups from genocide. Another was in 2015, when President Obama ordered US forces to intervene to save the monotheist Yazidi population from the terrorist Islamic State. It had seized territory in Syria and Iraq until it was later defeated militarily.

Among recent genocides was the killing of 200,00 Bosnian Muslims as part of Slobodan Milosevic’s project for a Greater Serbia. Above, graves for the reburial 6,000 Bosniak men and boys slaughtered at Srebrenica in 2010. Creative Commons License. Photo by Paul Katzenberger.

The Advancement of Minority Rights

While in dictatorships there continued to be widespread violation of minority rights and destruction of minority communities, democracies began to overcome their profound contradictions of majority rule being used as a tool for majority tyranny. Through the disciplined struggles of minority groups over the 19th and 20th centuries, the right of minorities not to be tyrannized by the majority is now understood to be a central tenet for democracy. The principle of minority rights has extended from political minorities to racial, ethnic, religious, national, linguistic, sexual and other minorities.

The right of minorities not to be tyrannized by the majority is now understood to be a central tenet for democracy. The principle of minority rights has extended . . . to racial, ethnic, religious, national, linguistic, sexual and other minorities.

Minority rights are also now embedded in international law. The United Nations adopted clear protections for minority groups in both the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (both adopted in 1948). Additional protections are in Article 27 of the UN's International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966) and the Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities (1993).

UN Conventions are often used after the fact as the basis for investigations by the UN Council on Human Rights, special tribunals and the International Criminal Court against those who have committed brutal crimes against minority groups. (For further discussion on prosecutions, see also Essential Principles in this unit and the History section in Accountability and Transparency.)

In most democracies, majority tyranny is no longer an accepted or protected practice. Many countries have established affirmative practices to respect minority rights and promote minority representation and greater equality.

In most democracies, majority tyranny is no longer an accepted or protected practice. Many countries have established affirmative practices to respect minority rights and promote minority representation and greater equality. Minority groups have advanced in representation in politics, employment, education and culture in nearly all democracies.

In recent decades, sexual minorities have also gained equal rights and representation and face reduced discrimination in many countries. Nevertheless, institutionalized racism and discrimination of minority groups remain established practices. As shown in the Country Studies, many minority groups face police repression, poverty, unequal opportunities and lack of economic resources as a result. There are few cases of significant reparations to overcome or repair the legacy of majority tyranny.

A Return to Majority Tyranny?

The recent rise of nationalist and chauvinist parties that seek to block immigration and maintain dominance of a racial majority has raised the prospect of a return of majority tyranny in a number of established democracies.

The recent rise of nationalist and chauvinist parties that seek to block immigration and maintain dominance of a racial majority has raised the prospect of a return of majority tyranny in a number of established democracies.

In Europe, these parties have gained majority power through elections, as in Hungary, Italy and, for a period from 2015 to 2023, Poland. Some smaller parties have entered majority coalitions, as in Sweden. In the Netherlands, an anti-immigrant party gained a plurality in recent elections but it's leader could not form a majority government without agreeing not to be prime minister (see Country Study in this section). Membership in the European Union and the Council of Europe require countries to adhere to constitutional protections of minority rights, limiting somewhat the actions of chauvinist political parties in power. The EU’s own internal controls were adopted recently to bar funds to Hungary and Poland for violating rule of law provisions, rights of migrants and LGBTQ+ rights.

In the United States, an openly chauvinist candidate won the presidency in 2016 and implemented policies to exclude all Muslims from the country and immigrants generally. This included restricting the number of asylum seekers given safe haven contrary to US obligations under international and domestic law.

While those restrictions were reversed under the succeeding president, Joe Biden, anti-immigrant political rhetoric remained high due to high levels of border crossings. The Republican Party and its former president, Donald Trump, continued to demand “a complete shutting down” of the border barring anyone seeking asylum from entering the United States. Running again for president in 2024, Trump pledged mass deportation of 11-13 million undocumented immigrants in the country using military forces and local and state police. With his victory in 2024, he immediately imposed even harsher anti-immigrant policies than his previous administration upon returning to office.

At the same time, elected legislatures in Republican-controlled states have used majority rule to limit the voting rights of racial and ethnic minorities ─ reminiscent of earlier periods in US history (see above).

Such cases, among others, are a reminder that democracy is neither easily gained nor kept. These countries’ recent practices only reinforce the essential principle that democracy requires minority rights.

The use of majority rule to impede the rights of the political minority has arisen in other countries as well, such as the Philippines and Turkey (the Country Study in this section). Political leaders in these countries have used election victories to adopt anti-democratic measures that impede political opposition and aim to ensure their continuation in power through political domination of the media, the judiciary, other institutions and the economy.

Such cases, among others, are a reminder that democracy is neither easily gained nor kept. These countries’ recent practices only reinforce the essential principle that democracy requires minority rights. “The will of the people” loses meaning when it is not achieved through free and fair means but rather by anti-democratic methods that do not protect the rights of minorities and political equality.

The content on this page was last updated on .