Summary

The Netherlands, situated across from Great Britain on the European continent, is a constitutional monarchy and parliamentary democracy with unitary structure. Formally, it exists within the Kingdom of the Netherlands, which has four constituent countries (the Netherlands, Aruba, Curaçao and Sint Maartens) as part of a unitary monarchy.

The Netherlands declared independence from the control of Spain in the 16th century. It quickly became a continental European power having a dominant position in seafaring, trade and control of foreign colonies.

Netherlands, CIA World Factbook

The country was neutral in both World Wars but was occupied by Nazi Germany from 1940-44. During the Nazi occupation, more than two-thirds of its Jewish population was killed. After liberation, the country returned to democratic governance, with a pluralist multiparty system and model welfare state.

Predominantly Nederland, or Dutch, by ethnicity (75 percent), the minority population grew to 25 percent in recent decades, with immigrants coming from European, Arab, African and former colonized countries.

The country is religiously mixed. The largest affiliations are Catholic (20 percent), Protestant (15 percent) and Islam (6 percent), while 55 percent adhere to no formal religion. Historically, the Netherlands adopted a policy of “multiculturalism” to promote coexistence of Catholic and Protestant “pillar” communities. Applied to the Muslim immigrant community, however, the policy tended to foster separation. The rise of anti-immigrant political parties has challenged the country’s tradition of tolerance and socially liberal policies. One such party won a plurality in 2023 parliamentary elections and has formed a governing coalition with center-right and center parties (see Current Issues).

The Netherlands is a small country in area (131st out of 195 countries) and in population (70th in the world at 18 million people in 2023). Yet, it is among the world's most dynamic economies according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). In projected 2024 figures, it is ranked 17th in the world in nominal GDP ($1.14 trillion) and 13th in nominal Gross National Income ($63,750 per capita).

History

From Early History to Independence

Distinct human cultures emerged in the territory of the Netherlands around 13,000 BCE. Hunter-gather communities intermixed with those adopting animal husbandry into the late BCE period, when Celtic and Germanic tribes migrated to the territory. The area was conquered by the Romans in the 1st century BCE and in the Middle Ages by the Franks under Clovis I and then by the Carolinian Empire under Charlemagne.

Within the framework of the Holy Roman Empire, the Austrian Hapsburgs and then the Spanish monarchy exerted authority over the Low Countries (what are today Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands). In 1568, the seven northern Low provinces (Netherlands) declared independence from Spain’s Charles V over issues of religion, taxation and privileges of the nobility. This sparked the Eighty Years War, also known as the Dutch Revolt.

The Seven Republics of the Netherlands operated as a republican confederation but with several states governed by a constitutional monarchy under the Protestant House of Orange

The Netherlands gained effective independence under the Union of Utrecht in 1579. Spain formally recognized its independence in 1648 under terms of the Treaty of Westphalia. The latter treaty ended the Thirty Years War and the religious conflicts between Catholic and Protestant states.

The Seven Republics of the Netherlands operated as a republican confederation but with several states governed by a constitutional monarchy under the Protestant House of Orange (the longest-lasting constitutional ruling family in Europe). In 1677, William III, the sovereign prince of Orange, married his first cousin Mary, the daughter of the future king of England, James II. On the throne, James II’s adherence to Catholicism and other actions were believed to threaten the state Church of England, prompting the British Parliament to invite William to invade. He defeated James II’s army as part of The Glorious Revolution. William and Mary briefly united the British and Dutch thrones.

The Dutch Golden Age

The period from 1584 to 1702 is known as the Golden Age in Dutch history. It was an era of expanded trade, economic development, colonial expansion, international influence, and significant contributions to Europe’s intellectual Enlightenment and culture.

The period from 1584 to 1702 is known as the Golden Age in Dutch history. It was an era of expanded trade, economic development, colonial expansion, international influence, and significant contributions to Europe’s intellectual Enlightenment and culture. With its major cities on the North Sea (Amsterdam, Rotterdam and the Hague), the Netherlands became one of the great seafaring nations of the world and established trading posts and colonies in strategic places, including South Africa, Brazil, Indonesia, Suriname and several Caribbean islands. Before trading it to Britain, the Netherlands empire included New Amsterdam (later renamed New York). Aside from New Amsterdam, which thrived as an independent entity, the Netherlands treated its colonies in much the same way as Great Britain, exploiting resources and imposing slavery or other forced labor practices.

The Netherlands was highly innovative in the development of technology, especially forms of seafaring and ways of protecting its below-sea-level cities through waterways. The Netherlands also innovated in areas of economic commerce. It is known as the first capitalist country, having introduced public stock companies, share trading, a stock exchange and insurance. It also introduced use of the windmill for energy. These innovations continue to be part of the foundation for the economy.

Establishment of Parliamentary Democracy

Since 1848, after a popular revolution, the Netherlands has had a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary democracy that has functioned continuously ever since, except for the Nazi occupation of 1940-44.

In 1795, Napoleon's army defeated the Netherlands to incorporate it into an emerging empire. With Napoleon’s final military defeat in 1815, independence was restored through the Kingdom of Netherlands in a union with Belgium and Luxembourg (the southern Low countries). In 1830, Belgium declared its own independence. In 1839, Luxembourg followed suit, leaving the Kingdom with its original seven regions.

Since 1848, after a popular revolution, the Netherlands has had a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary democracy that has functioned continuously ever since, except for the Nazi occupation of 1940-44. The legislature, or States General (which first met in the 15th century) has had a popularly elected House of Representatives together with a Senate, which is elected indirectly by the seven States Provincial. The franchise depended on limited property or wealth qualifications until 1917, when universal male suffrage was established. Women gained the full right to vote soon after, in 1919, one year before the United States.

The Binnenhof complex of buildings, originally built in the 13th century, has housed the Estates General since 1584. Shown here in 2020 on “coming out day.” Creative Commons License. Author: O. Seveno.

Neutrality and Occupation

The country's sizable Jewish population was rounded up and transported to extermination camps. Despite efforts of non-Jews to hide them . . . 100,000 Dutch Jews perished, or 70 percent of the prewar Jewish population.

The Netherlands remained neutral in both world wars, but Nazi Germany ignored its neutrality and occupied the country in 1940 as the Wehrmacht swept across Western Europe. A Dutch government was formed in exile in London and urged resistance, but this was limited. Under an oppressive Nazi administration, Dutch workers were put to forced labor. The country's sizable Jewish population was rounded up and transported to extermination camps. Despite efforts of non-Jews to hide them ─ the Netherlands has the second highest number of any country of “righteous Gentiles” honored by Israel ─ 100,000 Dutch Jews perished, or 70 percent of the prewar Jewish population. The country was liberated in 1944-45.

Postwar Expansion & Contraction

Like much of Western and Northern Europe, the Netherlands reconstituted its democratic government after the war. Despite initial hardship, the country saw both dynamic free-market growth and the development of broad social democratic policies providing guarantees of social welfare. The country has emerged as one the world’s largest economies and a model welfare state.

Despite initial hardship, the country saw both dynamic free-market growth and the development of broad social democratic policies providing guarantees of social welfare.

Post-war governments granted independence to former colonies such as Indonesia and Western New Guinea in 1949 (the latter became part of Indonesia in 1962). A composite kingdom was created in 1954 made up of remaining territories in the Caribbean. Suriname established its independence in 1975, while others retained country status (Aruba, Curaçao, and Sint Maarten) or municipal status (Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba) within the Kingdom. Since 2009, residents of these islands, have the right to vote in both Dutch and European Parliament elections.

After World War II, political parties rejected neutrality in foreign policy. The Netherlands joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) as an original member in April 1949. In 1952, it helped form the European Coal and Steel Community, the forerunner of today's European Union. The Netherlands has sought to stand out as a country with strong concerns for human rights and humanitarian issues internationally. It provides a fixed part of its GDP for foreign assistance (0.59 percent, or around $5 billion in 2020).

Majority Rule, Minority Rights

While still a constitutional monarchy, the king has only a formal role. The Constitution of the Netherlands establishes a parliamentary democracy, with a bicameral legislature. The Constitution has full protections for individual freedoms, minority rights and the rule of law, all of which are affirmed through membership in the Council of Europe and adherence to the European Convention on Human Rights.

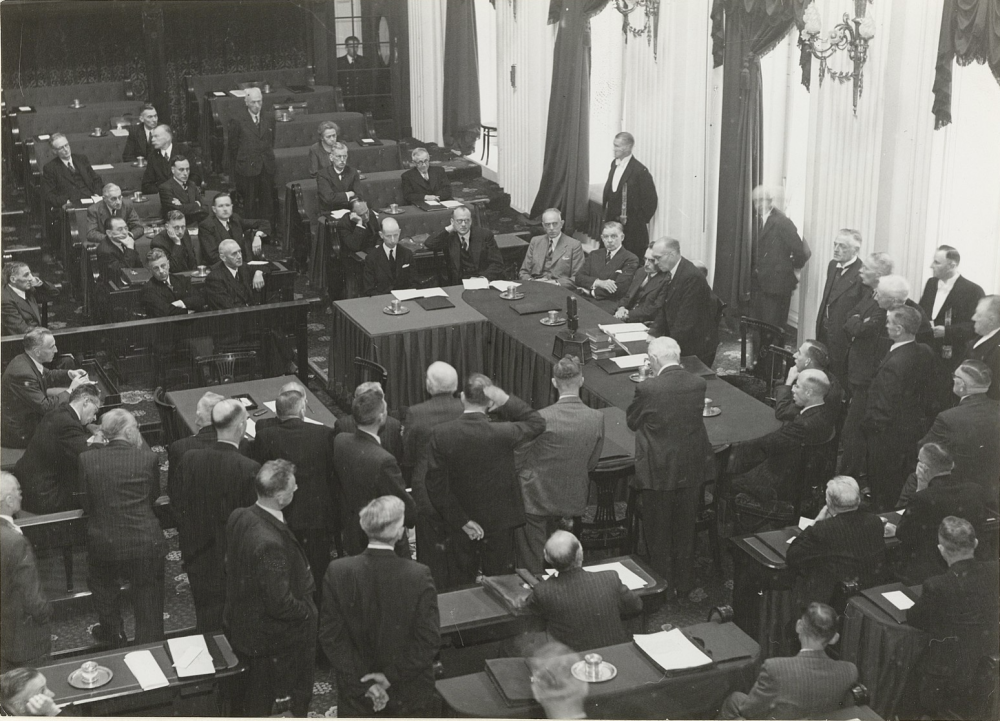

A meeting of the Tweede Kamer (second chamber), or House of Representatives, soon after liberation from Nazi occupation in October 1945. Creative Commons License. Courtesy of Rijksmuseum.

After amendments to the Constitution in 1956, the bicameral parliament (Estates-General) consists of a 75-member First Chamber (Eerste Kamer), or Senate, and a 150-member Second Chamber (Tweede Kamer), or House of Representatives. The Second Chamber is directly elected at least every four years by strict proportional representation, according to party lists. There is a low threshold for entering parliament (0.67 percent), with a large number of parties generally represented. The Second Chamber has powers to form the government, review cabinet decisions and policy, and initiate and amend legislation. The First Chamber, or Senate, has powers of review and its approval is necessary for legislation to be enacted. Its members are elected to four-year terms by provincial parliaments (Estates Provincial) following provincial elections.

Political Majorities and Minorities

Political parties represented in parliament are highly diverse, including conservative and liberal, rural and urban, religious-based and secular, pro-business and pro-labor, anti-immigrant and pro-immigrant, socialist and social democratic, and environmental.

Political parties represented in parliament are highly diverse, including conservative and liberal, rural and urban, religious-based and secular, pro-business and pro-labor, anti-immigrant and pro-immigrant, socialist and social democratic, and environmental. Dutch politics generally has had two leading parties, one right and one left, but no party has won a majority of the vote or seats in post-war elections.

With its low threshold for entering parliament, there have been at least seven and as many as seventeen parties represented since 1946. No single party or majority bloc has dominated, with right-left unity governments being common. In recent elections, a number of new parties emerged to splinter the political landscape further. In the most recent election (2023), fifteen parties won seats. There was a lengthy delay in forming a new government (see Current Issues).

The Post-War Period to Present

In the post-World War II period, there were two leading parties, the Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA) on the center-right and the Labor Party (PvdA) on the center-left. Rural, religious-based, liberal and socialist parties also gained representation. In the decades since World War II, the Netherlands saw a series of left-led or right-led coalition governments, as well as five unity governments composed primarily of the main left and right parties.

A vote during the 1972 Congress of the Netherlands Labour Party (PvdA), which was a dominant party in the post-World War II period. Creative Commons License. Dutch National Archives.

In 2002, an anti-immigrant politician rose to prominence with a self-named party, the Pim Fortuyn List (LPF). He challenged the country’s open immigration and multiculturalist policies (see below) and attacked Islam as a homophobic and “barbaric” religion. Prior to the election, Fortuyn was killed by an animal rights activist. Based in part on a sympathy vote, the LPF won second place in the voting ─ unprecedented for a new party. The Christian Democratic Alliance (CDA) included the LPF in a four-party right-wing government, but it fell after five months (the shortest-lived in post-war history). In 2003 elections, the LPM lost most of its seats and the CDA formed a right-coalition government without LPF. Still, the LPF’s initial success presaged the rise of anti-immigrant parties (see below).

In the 2010 and 2012 elections, the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD), which combines a pro-free market and socially liberal platform, supplanted the more conservative CDA as the major right-wing party. The Labor Party remained the second largest, slightly behind VVD in both elections.

The "Pillars" and Failures of Multiculturalism

The Dutch reputation for multiculturalism and tolerance originates from the country's history of "pillar" communities, which were adopted as a legacy of the Wars of Religion. Separate state-supported “pillars” allowed Catholic, Protestant and secular communities to live in one society without conflict.

The Dutch reputation for multiculturalism and tolerance originates from the country's history of "pillar" communities, which were adopted as a legacy of the Wars of Religion. Separate state-supported “pillars” allowed Catholic, Protestant and secular communities to live in one society without conflict.

In practical terms, this approach meant state subsidies for Protestant, Catholic and social democratic institutions, including for clerics, unions, newspapers, broadcast stations, universities and schools and other social or religious-based institutions. The aim was to ensure that no religious or secular group would be excluded from public life. Immigration policy followed this history and “pillarization” extended to the Muslim community.

While the original pillars had resulted in the broad intermixing of religious and secular communities (and ultimately a largely secular society), the policy had the opposite effect for Muslim communities. The Social and Cultural Planning Office published a report in 2004 that found that the policy had encouraged greater insularity and resulted in alienation from majority Dutch culture and politics (see link in Resources). The report recommended job, education and social policies aimed at assimilation and integration of immigrants and foreign communities.

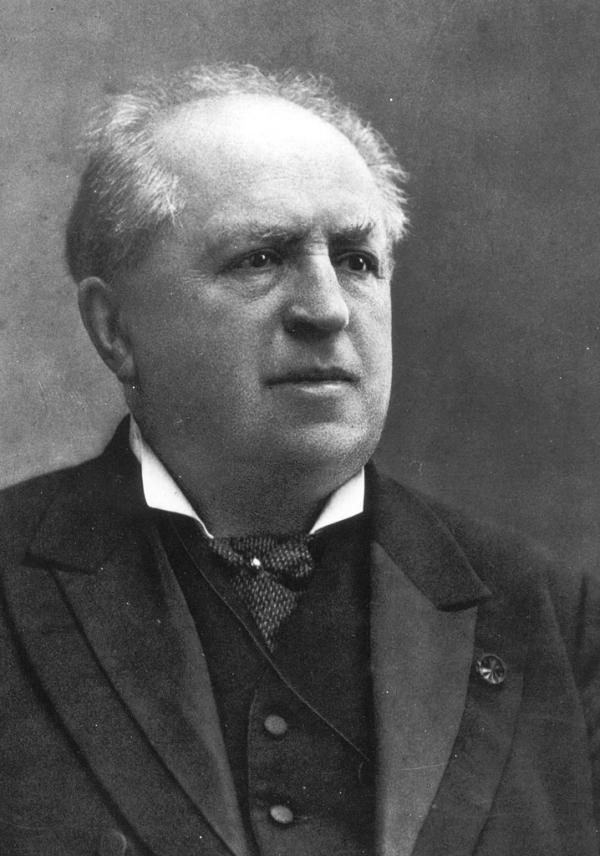

Abraham Kuyper, a religious and political leader, developed the idea of pillarization. Shown here in 1905 as Minister President. Public Domain.

The Report analyzed the rise of Pim Fortuyn and his political party as being rooted in widely held perceptions that immigrants took jobs from native-born Dutch citizens and that “multiculturalism” encouraged religious separatism and extremism.

A Second Political Murder

In November 2004, the Dutch public was shocked by another brutal public murder. A Moroccan immigrant who had joined an Islamist terrorist network assassinated the director Theo van Gogh because of a film he made depicting the mistreatment of women in fundamentalist Islamic communities.

Anti-immigrant sentiment rose. The Christian Democrat-led government adopted a plan to expel 26,000 jobless migrants and reduce public spending for minority and immigrant communities. While the plan enjoyed popular support, one party (Democrats ’66) withdrew from the coalition to force new elections.

The 2006 elections splintered, with neither right nor left able to form a coalition. This resulted in a unity government of the Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA) and the Labor Party (PvdA). They adopted a platform called “Living Together, Working Together” that focused on the recommendations of the Social and Economic Planning Office: jobs, education and a new assimilation policy for immigrants (see above). The government lasted nearly a full term (the PvdA withdrew in protest of the country’s participation in NATO’s military operations in Afghanistan).

Political extremism in the Netherlands emerged in the early 2000s as a serious threat to free expression. The film director Theo van Gogh, whose film Succession depicted harsh treatment of women under Islamist rule, was murdered in November 2004 by a religious extremist. Creative Commons License. Photo by Sjakkelien Vollebregt.

Changing Alignments

The resulting 2010 election had surprising and lasting results. The center-right People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD), also known as Liberals, narrowly emerged as the top vote-getter over the Labor Party (31 to 30 seats). The previously dominant CDA fell dramatically to fourth place, behind a new anti-immigrant party, the Party of Freedom (PVV). Its leader Geert Wilders was at the time facing charges for hate speech for encouraging mass expulsion of immigrants (he was convicted but ultimately acquitted on appeal).

The Liberals’ leader, Mark Rutte, formed a center-right minority coalition government with the CDA and Democrats 66, a smaller social liberal party. But it relied on support of members of the PVV for a parliamentary majority. When Prime Minister Rutte proposed a law backed by Geert Wilders to ban Islamic full-face and body coverings (the niqab and burqa), the Democrats ’66 withdrew from the government, forcing new elections.

Mark Rutte, shown at the European Commission in March 2023, was prime minister of Netherlands from 2010 to 2024 as leader of the liberal Party for Freedom and Democracy. Creative Commons License. Photo by Christophe Licoppe.

In the early 2012 general elections, Rutte’s VVD retained its top position (42 seats) with the Labor Party (PvdA) still close behind (38 seats). The Party of Freedom (PVV) lost support and the Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA) continued to decline.

Both main parties refused participation by the PVV. As a result, a compromise unity government of the VVD, CDA and PvdA was formed that lasted a full four-year term. It increased funding for education and assimilation policies but banned income assistance to immigrants who did not speak Dutch. Overall, the government was less welcoming to immigrants. In response to the migration crisis of 2015-16, when 2 million people sought asylum in Europe from war-torn Syria and Afghanistan, nearly all Dutch parties, including the PvdA, called for restricting immigration. The country accepted just 50,000 migrants. (By comparison, Germany accepted the largest number, about 1 million.)

Current Issues

Elections in 2017, 2021 and especially 2023 further altered Netherland’s political landscape. There is now a consistent political majority of far-right and center-right parties adopting less tolerant policies towards immigrants and minority rights.

In 2017, the Liberals (VVD) had a much reduced 21.3 percent of the vote while the Labor Party (PvdA) saw a dramatic drop to 5.7 percent (widely seen as its base opposing the party’s participation in the center-right coalition government). The anti-immigrant Freedom Party (PVV), running on a platform of “de-Islamization,” won a similar amount as previous elections, 13 percent, but now had the second strongest showing. The Christian Democratic Alliance (CDA) also adopted a hardline anti-immigrant policy and rebounded to 12 percent. Beyond that, the electorate splintered, putting nine other parties in parliament.

Elections in 2017, 2021 and especially 2023 further altered Netherland’s political landscape. There is now a consistent political majority of far-right and center-right parties adopting less tolerant policies towards immigrants and minority rights.

With such fracturing, it took a record 255 days for the Liberals’ leader, Mark Rutte, to form a one-seat majority center-right government. Despite not including the far-right PVV, the government adopted harsher immigration policies. Asylum seekers were not just limited in number but being kept in detention facilities for months. Kingdom territories in the Caribbean rejected thousands of Venezuelan asylum seekers altogether. The law to ban religious face coverings in public spaces was re-introduced.

Parliament approved a new Intelligence and Security Act, which allows broad surveillance powers for security agencies, and the proposal to ban religious face coverings on public transport and in public spaces like schools and government buildings. Notwithstanding these harsher polices, the government adopted a "Kinderpardon” in 2019 that allowed nearly one-thousand stateless children previously denied asylum to re-apply to obtain residence.

Also, just two months before its full term in January 2021, the government was forced to resign due to a major scandal involving a discriminatory practice by the Tax and Customs Administration dating to 2002. An oversight agency found that the Tax and Customs Administration made illegal use of applicants’ personal data to deny childcare allowances to thousands of dual-national citizens. A special parliament committee found that between 9,000 and 26,000 families were entitled to compensation.

Proportional systems allocate seats in parliament and municipal councils according to a party’s percentage of the vote. Recent elections have brought about changing alignments in Dutch politics. Above, election posters for 2018 Municipal Elections. Creative Commons License. Photo by Steven Lek.

The elections in March 2021 returned a similar result as 2017 for the VVD (21 percent), but the pro-immigrant Democrats ’66 emerged as the surprise second largest party (16 percent). The PVV retained its 13 percent, while the Forum for Democracy (FvD), a new anti-EU and far-right nationalist party, got 5 percent. There continued to be reduced support for the main left-wing parties (Labor, Socialists and Greens). Smaller parties filled their place. A record total of seventeen parties entered parliament. This time, it took nine months for VVD leader Mark Rutte to form his fourth government. The center-right coalition lasted only eighteen months. In July 2023, D66 resigned over Prime Minister Rutte’s insistence on a policy to delay for two years family reunification of immigrants granted permanent asylum.

Elections in October 2023 again shifted the political terrain. The far-right Freedom Party (PVV) won a solid plurality of the vote at 23.5 percent (37 seats). A coalition of the Labor Party (PvdA) and Greens came in second at 16 percent (25 seats). The Liberals (VVD) dropped to 15 percent (24 seats). Two centrist parties, New Social Contract and D66, won 13 and 6 percent, respectively, with eight other parties getting seats.

The PVV’s lead position in the country’s politics shook the European Union and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization since the party, once firmly Euroskeptic and anti-NATO, remains lukewarm towards Dutch membership in both institutions and is equivocal on NATO’s most important security issue. The PVV condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 but its leader, Geert Wilders, has called for an end to Dutch military support to Ukraine and rejected any further acceptance of Ukrainian refugees (100,000 were admitted outside strict immigration limits imposed by previous governments).

On foreign policy, the VVD’s and New Social Contract’s positions held. The government retains the Netherlands’ commitment to the EU and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

It took again nine months to form a government. Wilders, who was twice tried in court for hate speech (see above), tried to form a government but his lead negotiator withdrew due to fraud allegations. Negotiations remained contentious as different negotiators tried their hand until Wilders agreed not to serve in the government. A compromise coalition was formed headed by an independent civil servant, Dick Schoof. It includes ministers from the PVV, VVD, the centrist New Social Contract (NSC) and the right-wing Farmer-Citizen Movement (BBB).

The policy statement of the Schoof government on domestic policies is generally vague — except on immigration and agricultural policy. There, it promises to strictly limit the number of immigrants and to abandon EU environmental limits on nitrogen use in farming (a demand of the Farmer-Citizen Movement).

On foreign policy, the VVD’s and New Social Contract’s positions held. The government retains the Netherlands’ commitment to the EU and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, including by increasing defense spending to more than 2 percent of GDP and maintaining substantial military support for Ukraine. The VVD’s Mark Rutte left his caretaker position as prime minister to assume the position of General Secretary of NATO.

While there generally has been growing intolerance towards immigration and support for restricting asylum, there are other developments in the area of minority rights in recent years.

While there generally has been growing intolerance towards immigration and support for restricting asylum, there are other developments in the area of minority rights in recent years. The 2020 killing of George Floyd resulted in large anti-racism protests and prompted a partial reckoning with the country’s racist past and practices.

For example, a number of municipalities finally took the step to ban Black Pete. A centuries-old celebration dating from the Middle Ages, Black Pete is an historical demonic figure who supposedly accompanies Santa Claus at Christmastime. Costumes had taken on explicitly racist caricatures in recent decades (see article in Resources).

Also, in December 2022, Prime Minister Mark Rutte issued a formal apology for the Netherlands’ role in slavery and the slave trade. The Dutch East India and West India Companies both took part in the slave trade over two centuries, transporting 800,000 enslaved persons to Dutch colonies in Brazil, Suriname, Indonesia and Caribbean islands. The Netherlands abolished slavery in its empire only in 1863 (and even then required forced labor for 10 years as compensation to slave owners). Following decolonization, no previous government had ever addressed the issue. Critics noted that Rutte’s apology ignored requests of former colonies for reparations.

A number of Dutch municipalities responded to protests to ban Black Pete, a traditional figure in Christmastime parades usually depicted in racist caricature. Creative Commons License. Photo by Arnold Bartels.

The content on this page was last updated on .