Athenian Democracy and the Roman Republic

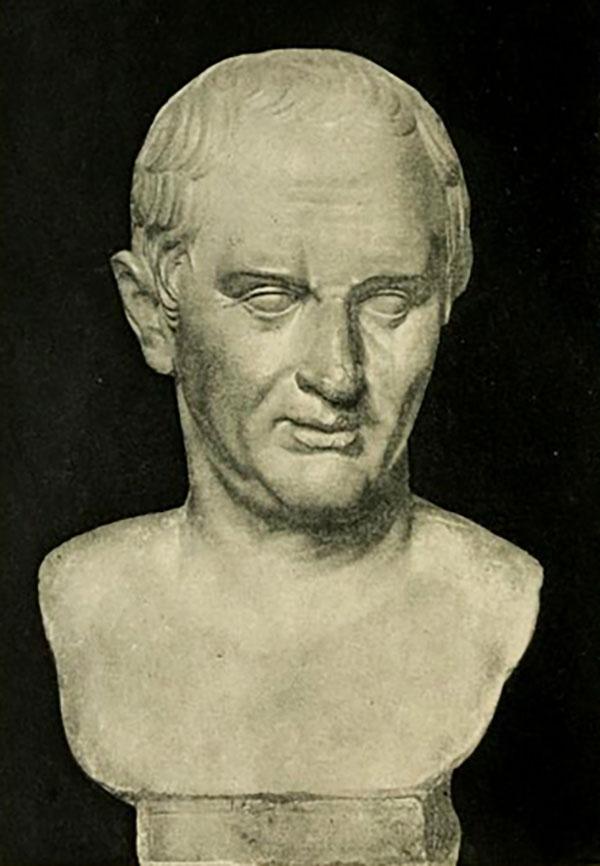

A bust of the Roman statesman and orator Marcus Tullius Cicero, who extolled the “mixed or balanced" constitution of the Roman Republic.

Constitutional limits are usually considered more a phenomenon of modern polities. Still, constitutions granting rights and limiting power existed through established laws from ancient times. In many Greek city-states, constitutions provided the wealthy or an aristocracy certain power in relation to a ruler or rulers. Even tyrannies had laws granting rights or limiting power. One example is the Cylinder of Cyrus, from the 6th century BCE, in which the emperor established religious tolerance and freedom of movement within his early Persian empire.

Ancient Athens from the late 6th to 4th centuries BCE also had constitutional limits. The city-state adopted a form of direct democracy by which citizens gathered in assembly to decide all major issues of war, taxation, trade, law and politics and to select the city-state’s generals and other magistrates. But disputes of property and contract were resolved in courts through juries composed of the citizenry acting according to existing laws. During the Enlightenment, most political thinkers considered Athenian democracy a dangerous form of rule, subject to tyranny of the mob. Yet, its democratic system has no record of the citizenry’s loss of control or suspension of laws. Rather, essential constitutional limits were observed. Over the 19th and 20th centuries, Athenian democracy became seen as a model for establishing constitutional rule with political equality across all classes.

Republican Rome had a constitution that evolved over centuries following the expulsion of a king who had abused his absolute power in the 6th century BCE. The monarchy was replaced by two consuls elected by popular assembly.

Republican Rome had a constitution that evolved over centuries following the expulsion of a king who had abused his absolute power in the 6th century BCE. The monarchy was replaced by two consuls elected by popular assembly. While all citizens attending assemblies voted, the main assembly’s vote was weighted by wealth. Most powers of administration and decision-making were held by an aristocracy of wealthy landowners who could afford to serve in various elected offices. The Senate, which proposed and affirmed laws, was comprised of those appointed out of those elected offices. Soon after the fall of the monarchy, class struggle expanded power to the people to elect their own Tribunes who could veto decisions affecting the lower class of plebeians (small landowners, merchants and laborers). The Roman statesman Cicero described the system as “not a monarchy, nor aristocracy, nor a democracy,” but a “mixed or balanced constitution.” In the end, however, the Republic fell to dictatorship due to the accumulation of power by consuls and generals.

The Magna Carta

The Magna Carta limited the monarchy’s powers and established the principle that even a king claiming the divine right to rule had to follow laws and customs and respect the privileges and property rights of their subjects.

Modern constitutional limits on government are commonly traced to England’s Magna Carta Libertatum (Great Charter of Liberties). Signed in 1215 CE, the agreement followed a rebellion of feudal barons against the monarch, King John, who had attempted to impose additional taxes by force. The Magna Carta limited the monarchy’s powers and established the principle that even a king claiming the divine right to rule had to follow laws and customs and respect the privileges and property rights of their subjects. Most importantly, the king had to seek consent of an assembly made up of nobility, high clergy, gentry and townsmen before imposing taxes or raising an army for war.

The Magna Carta led to an early incarnation of England’s modern Parliament. It met for the first time in 1295. Territorial representatives (or tax-payers) were then separated in 1341 to form the lower House of Commons. The House of Lords, initially more powerful, comprised nobility appointed by the monarch and high clergy.

The British Model

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, known commonly as the UK, still does not have a formal constitution. It is governed according to the accumulation of parliamentary law, treaty, traditions and practices built on the Great Charter (as well as an earlier Charter of Liberties signed in 1100). Over the centuries, the House of Commons came to dominate the "upper" House of Lords due to its greater representation.

The first House of Commons meeting in 1833 after the Reform Act, which expanded representation. Painting by Sir George Hayter.

Today, the House of Commons is the seat of political power. The monarch is now a titular head of state retaining only a formal power to nominate a government based on the leading party in parliament. The House of Lords consists largely of members appointed for life by the monarch on the recommendation of the prime minister (some high-ranking clergy and hereditary peers remain). While the House of Lords retains oversight and advisory powers to return legislation for further deliberation, it cannot prevent final enactment of laws.

A select group of members known as the Law Lords served as the country's court of highest appeal until 2009, when a separate Supreme Court was created under the Constitutional Reform Act. For the first time, the judicial function was separated from the legislative and executive branches (although still comprised of members approved by the House of Lords).

The US Model

The United States Constitution establishes a formal written foundational law, but its practice, too, is determined by laws, tradition and judicial interpretation.

As noted in Consent of the Governed and Free Elections, the framers of the US Constitution balanced concerns for the dangers posed by a too-weak national government created under the Articles of Confederation with those inherent in establishing a too-powerful executive. The framers drew from practices of republican Rome, writings of Enlightenment philosophers and a study of past and current constitutions to craft a “mixed or balanced” model of government.

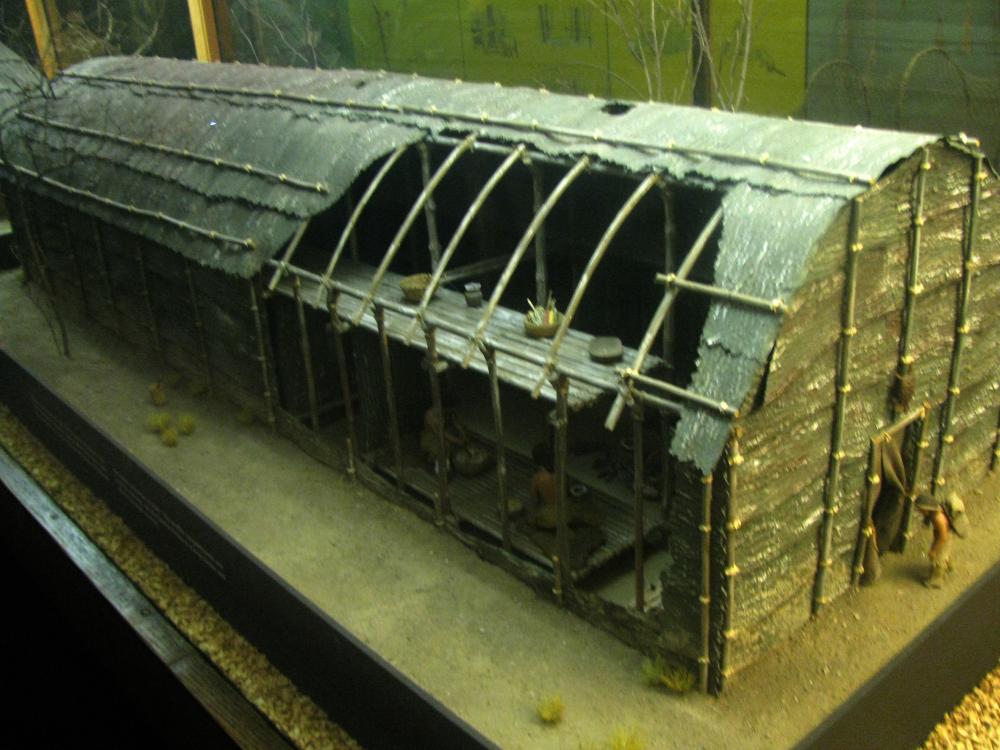

The basic federal structure of the United States was influenced most by the Haudenosaunee (“peoples of the longhouse”), also known as the Iroquois Confederacy. Above, a model of the traditional Iroquois Confederacy Longhouse as shown in the American Museum of Natural History. Creative Commons License. Photo by Janine and Jim Eden.

The basic federal structure uniting different sovereign states was influenced most by the Haudenosaunee (“peoples of the longhouse”), also known as the Iroquois Confederacy. Located in regions of New York and Quebec, the Confederacy united the Cayuga, Mohawk, Onondaga, Oneida, Seneca and Tuscarora nations in a defensive and cooperative alliance that left internal affairs and governance to each nation. The Founders of the United States drew on their knowledge of and encounters with Native American confederacies, but especially the Iroquois’s Great League of Peace, in crafting the original union of states (see Congressional Resolution and other texts in Resources).

The framers drew from practices of republican Rome, writings of Enlightenment philosophers, and a study of past and current constitutions to craft a “mixed or balanced” model of government.

The principle of separation of powers that the US Constitution adopted was influenced most by the writings of Baron de Montesquieu in The Spirit of Laws. Montesquieu describes the ideal government as having three branches (the executive, legislative and judicial), each with specified and limited powers so that no one branch may dominate the other. He wrote, “There would be an end of everything were the same man or the same body, whether of the nobles or of the people, to exercise those three powers, that of enacting laws, that of executing the public resolutions, and of trying the causes of individuals.” In relation to the US Constitution, James Madison elaborated most on the theory of separation of powers and the checks and balances among the different branches of government in several of the Federalist Papers (see links in Resources).

In the United States, a president and vice president hold the only nationally elected offices and head the executive branch as representative of all the people. While the Constitution establishes a strong executive, the president's chief responsibility is to “faithfully execute the laws” passed by the legislature or Congress. The executive has power to veto legislation, but a two-thirds majority of both houses of Congress may override it. The president’s other main responsibility is as commander-in-chief of the armed forces and as head of government in relation to foreign states. Yet, only Congress has power to declare or authorize war. The president appoints executive officers, including ambassadors, and federal judges, but the Senate must advise and consent to each of them, as well as to approve international treaties. Both branches thus have checks and balances on the other’s power. Congress itself is divided into two chambers and neither chamber has dominant power.

The principle of separation of powers adopted in the US Constitution was influenced most by the writings of Montesquieu in The Spirit of Laws. He wrote, 'There would be an end of everything were the same man or the same body . . . to exercise those three powers, that of enacting laws, that of executing the public resolutions, and of trying the causes of individuals.'

The House of Representatives, currently with 435 members, is elected by popular vote every two years in districts allotted to the states proportionally according to population as enumerated in a decennial census. The Senate, designed to prevent dominance by more populated and larger states, is made up of two members from each state regardless of population size. Terms are six years instead of two. Legislation generally originates in the House, but the Senate must approve all laws.

Within bicameral systems, Senates were considered to represent more the aristocracy or landed gentry to separate them from the more popularly elected chamber. Thus, the members of the Senate originally were indirectly elected through a state’s legislature. The original premise changed (in theory) with the direct election of Senators established in the 17th Amendment (there is now direct election of Senators as established in the 17th Amendment).

A separate federal judiciary exists to resolve disputes and review laws. In theory, it is protected from both elected branches of government through lifetime appointment. Federal judges may be removed only by impeachment by the House and conviction by the Senate for “high crimes and misdemeanors.” The House and Senate possess the same power to impeach and convict the country’s national officers.

The US Supreme Court is the final court of appeal. Its decisions and the Constitution are considered “the law of the land” and must be respected by the states and other branches of government.

Amendments to the Constitution, especially the first 10, known as the Bill of Rights, and also the post–Civil War 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments, expanded the federal government’s reach to grant and protect all citizens’ rights. At the same time, the Tenth Amendment retains the federal structure mentioned above. While states must have a republican form of government, they have autonomy and sovereignty with respect to their own governance.

The country's multilayered constitutional system of government is often blamed for a lack of timely or decisive action on important matters and critiqued for anti-majoritarian features.

The country's multilayered constitutional system of government is often blamed for a lack of timely or decisive action on important matters and critiqued for anti-majoritarian features. This was most notably the case on the issues of slavery and Jim Crow segregation. Southern states held sufficient legislative power to block antislavery and anti-discrimination laws, expand the reach of slavery and, later, enact the practice of legalized discrimination (see also History in Free Elections and Majority Rule, Minority Rights).

A similar historical debate has existed over the Supreme Court’s overreaching power to determine the “law of the land.” This power protected forms of majority tyranny such as slavery, segregation and the forced removal of Native American nations even when clearly contrary to provisions in the Constitution. Debate has resumed in light of recent actions of the Supreme Court limiting or restricting rights that had been firmly established by previous decisions (most notably the right to vote and the right to an abortion).

A more recent ruling granting the president immunity from prosecution for violating the law has raised additional concerns, leading some constitutional scholars to state that the current Supreme Court has “unbalanced the Constitution” (see also “Among the Most Challenging Cases" below and Current Issues in US Country Study). Still, most historians contend that a key reason for America's stability and survival as a democracy over two-and-a-half centuries has been the layered constitutional limits in the US system.

European Models

Most European countries passed through periods of absolute monarchy and developed varied forms of constitutional limits over time due to revolutions, civil or external wars or by more peaceful reform.

Most European countries passed through periods of absolute monarchy and developed varied forms of constitutional limits over time due to revolutions, civil or external wars or by more peaceful reform.

A notable case is that of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1795). The largest European territory of its time, the Commonwealth adopted an aristocratic system to replace absolute monarchy through a covenant called the Henrician Articles. Unusual for the time, the monarch became a non-hereditary position elected by the Sejm or parliament, composed of an elected aristocracy. As well, the king could not raise taxes or declare war without the Sejm’s consent.

The Henrician Articles, however, included what was called the liberum veto, allowing any member of the Sejm to veto legislation. This power proved destabilizing by allowing foreign interference to bribe individual Sejm members to exercise their veto and thus thwart effective governance. The kingdom ultimately became subject to partial partitions by neighboring empires (Austria, Russia and Germany). The Commonwealth tried to forestall further partition by adopting a constitution in 1791 forming a full parliamentary monarchy and extending political rights beyond the nobility. Poland’s three autocratic neighbors responded by occupying and partitioning all Commonwealth lands for the next 125 years. Poland and Lithuania regained independence only in 1918 (see also Poland Country Study).

In both parliamentary and mixed-presidential systems, there are constitutional limits established through a separation of powers, including an independent judiciary and systems of rule of law, transparency and accountability, and the granting and protection of human rights.

Today, most European countries have different forms of parliamentary democracy. Some, such as The Netherlands, retain a formal constitutional monarchy. Unlike the United Kingdom, however, it has a written constitution. Most parliamentary democracies are republics, like Germany and Italy. They elect presidents, or heads of state, through a vote of parliament but limit their functions (see Country Studies).

The other major European model is that of France (see Country Study in this section). It has a mixed presidential-parliamentary system drawing upon features of its previous republics. Since 1958 (with the establishment of the Fifth Republic), the president acts as head of state and plays a leading role in setting national policies, particularly in foreign and security affairs. After 1989, Poland and the Czech Republic adopted similar mixed systems.

In both parliamentary and mixed-presidential systems, there are constitutional limits established through a separation of powers, including an independent judiciary and systems of rule of law, accountability and transparency and the granting and protection of human rights. Basic human rights and rule of law are further protected today through ratification of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), which recommits states to UN international human rights covenants and is a requirement of membership in both the European Union and the Council of Europe (see also section on Human Rights). Through the European Union, the principle of subsidiarity is generally applied, similar to the US Constitution’s principle of federalism. It states that decisions affecting specific local or ethnic communities should be made at the lowest level.

The Rise of Dictatorship

During much of the 19th and 20th centuries, the mixed progress of constitutional democracy seen in Europe and North and South America was stymied elsewhere by the continuation of absolute monarchies, other forms of authoritarianism and the rise of strongman dictatorships and military juntas.

In the 20th century, new forms of dictatorship, such as Fascist and Communist regimes, apartheid in South Africa and theocracy also emerged. These regimes . . . concentrated power so completely that they are referred to as totalitarian systems.

In the 20th century, new forms of dictatorship, such as Fascist and Communist regimes, apartheid in South Africa and theocracy also emerged. These latter regimes, based on political, racial or religious ideologies, concentrated power so completely that they are referred to as totalitarian systems. They reflect Montesquieu’s warning of “the end of everything” when all power is held by one person, clique or political or ethnic group.

Among totalitarian regimes, Adolf Hitler's Nazi regime in Germany and Benito Mussolini’s Fascist regime in Italy formally acted under prior constitutions. But since parliaments were under their firm control, they had legislation adopted that centralized state power in themselves, overrode prior constitutional limits or simply acted without any legal authority to institute nationalist dictatorships with grand imperialist visions of conquest. (Other fascist regimes arose and governed in similar fashion, as in Spain and Portugal, but without similar imperialist vision.)

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) adopted a new constitution to establish the model for communist regimes. On paper, the Soviet constitution granted political, economic and social rights. In practice, it centralized control within the Communist Party and ultimately in its dominant leader, the General Secretary. To consolidate power, both fascist and communist leaders unleashed state terror of unprecedented scope on the population, including mass imprisonment, mass executions, mass starvation and genocide.

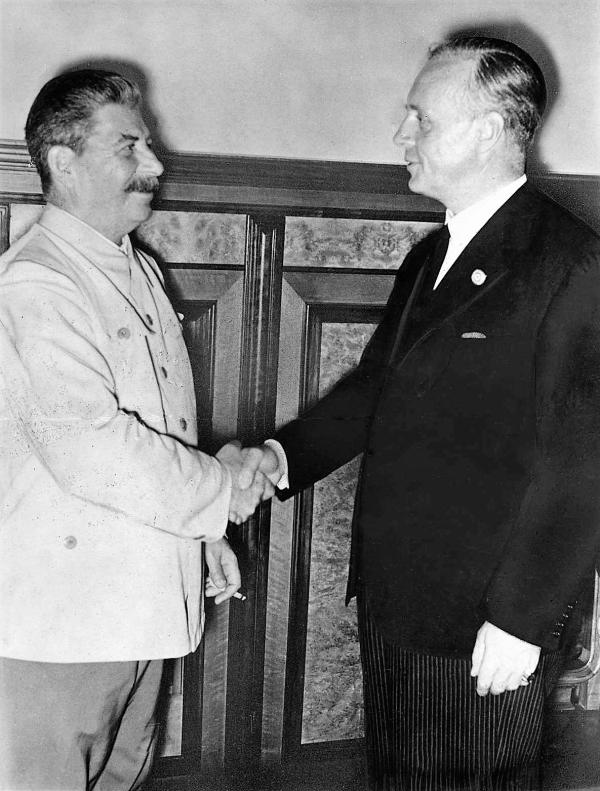

Above, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin greets Nazi Foreign Minister, Joachim Ribbentrop, in Moscow, August 23, 1939 for the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Its secret protocols divided Eastern Europe between Germany and the USSR, showing the affinity of the two totalitarian regimes. Creative Commons License. German Federal Archives.

An affinity of totalitarian regimes was seen when Nazi Germany joined fascist Italy and imperial Japan in the Tri-Partite Pact and when the Soviet Union joined Nazi Germany in the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact to launch the cataclysm of World War II. With great brutality, these four powers occupied much of Europe, Asia, the Middle East and North Africa. Nazi Germany, taking its racial ideology to the most extreme, perpetrated the Holocaust, murdering 6 million Jews, fully two-thirds of European Jewry.

Hitler, with broader imperialist visions for Lebensraum (“living space”), broke his pact with Stalin and invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941. The USSR then joined the wartime Allies to help defeat Nazi Germany. But its earlier imperialist vision was fulfilled by formally incorporating the Baltic States and Moldova into the USSR and by occupying nearly all of Eastern Europe, where it installed copies of its communist police state. The USSR also aided takeovers of countries by communist guerilla movements in China, North Korea and Vietnam.

The Post-War Expansion of Democracy

Even with the Soviet occupation of Eastern Europe and the rise of other communist dictatorships, the adoption of democracy with constitutional limits increased steadily after the defeat of the Axis Powers in World War II. Democratic governance was restored in most Western European countries. Under the oversight of the United States and other Allies, the war’s militaristic instigators — Germany (in its western part), Italy and Japan — all became established democracies with constitutional limits. (Eastern Germany, under Soviet occupation, had a communist dictatorship until 1989. It reunified with western Germany in 1990 under the latter’s Basic Law.)

In 1947, India emerged from under British colonial rule as the world’s largest democracy. In 1948, Israel was granted statehood under the UN’s partition plan and emerged as a stable democracy in the Middle East (see Country Study). In 1974-75, popular movements for democracy in Spain, Portugal and Greece succeeded in overthrowing fascist and military dictatorships.

[T]he adoption of democracy with constitutional limits increased steadily after the defeat of the Axis Powers in World War II.

Starting in the late 1940s, military dictatorships and strongman rule in Latin America also started to be overcome ─ in fits and starts. Today, democracy is the dominant form of government on the continent.

Decolonization in the 1950s and 1960s saw more dictatorships than democratic governments replace colonial administration in Asia and Africa. But starting in the 1980s, “people power” and other reform movements brought about a progressive adoption of electoral democracy and constitutional systems in an increasing number of African and Asian countries.

In the post-war period, the Soviet bloc (formalized in the Warsaw Pact) posed a military and political challenge to the Transatlantic Alliance of democratic countries (the North Atlantic Treaty Organization or NATO). Called the Cold War, the conflict lasted 44 years. Ultimately, however, communism was overthrown by a series of popular revolutions, first in the Eastern European bloc of countries in 1989, and then in the Soviet Union itself from 1989 to 1991. The USSR was formally dissolved in December 1991. Democracies were established in many of these post-communist republics.

Is Constitutional Democracy Ebbing?

Since 2005, the trend towards democracy with constitutional limits appears to have ebbed. Freedom House's 2024 Freedom in the World survey reports the eighteenth straight year in which scores in political rights and civil liberties declined in more countries than where they increased. Indeed, with India falling to the “partly free” category under a Hindu nationalist government, a majority of the world’s people now live in countries categorized as “partly free” (25 percent) or “not free” (35 percent), that is in systems where constitutional limits are only partially respected or not at all. The following is a review of continents and regions in this period, with Democracy Web Country Studies and sections linked where referenced.

Since 2005, the trend towards democracy with constitutional limits appears to have ebbed. . . . [The] 2024 Freedom in the World survey reports the eighteenth straight year in which scores in political rights and civil liberties declined in more countries than where they increased.

Many countries emerging from the former Soviet Union replaced communist dictatorship with authoritarian rule, most notably the Russian Federation itself but also Azerbaijan, Belarus and all Central Asian countries (an example is Uzbekistan, the Country Study in this section). In Central and Eastern Europe, some countries that had been considered “consolidated democracies” in the 1990s and 2000s slipped back in rankings, such as Poland and, even more so, Hungary, now in the “partly free” category.

After the death of its original leader, Mao Zedong, the People’s Republic of China adopted a hybrid communist political system with capitalist features. But mostly it remained a system without constitutional limits on state power and no protections of human rights (see Country Studies of China in Freedom of Expression and Freedom of Association). Under its current leader, Xi Jinping, the communist government has reverted back to more totalitarian practices.

Most Middle Eastern and North African countries retain monarchies, theocracies and other types of authoritarian government (as in Iran, Morocco, Saudi Arabia and Syria). Tunisia, which emerged as the one significant democratic gain from the 2011 Arab Spring protests, has reverted to anti-constitutional rule. Even Israel, the only full democracy in the Middle East and Northern Africa today, has seen its scores diminish due to attempts to establish government control over the judiciary, discrimination of Arab minorities within Israel, and ongoing human rights violations in the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip, which are both also considered “not free.”

In Sub-Saharan Africa, there is a recent trend towards consolidation of military dictatorship and other authoritarian rule. The people of Sudan and Uganda continue to challenge ruling regimes for greater democratic freedoms, but these countries remain firmly in the “not free” category, with Sudan now riven by civil war between rival generals.

Notwithstanding the recent downward trend, the advance of democracy since the end of World War II is impressive. From 1973, when Freedom House began its annual survey, to 2006, the world saw a substantial rise in the number of electoral democracies and in the number of “free countries” with constitutional limits firmly established.

In Latin America, Cuba remains the most flagrant violator of human rights on the continent. Venezuela is now not far behind. “Partly free” countries such as Bolivia and Guatemala (the Country Study in this section), although they have had recent gains, reflect the difficult history on the continent in establishing stable democratic systems with constitutional protections against abuse of power.

Notwithstanding the recent downward trend, the advance of democracy since the end of World War II is impressive. From 1973, when Freedom House began its annual Freedom in the World survey, the world saw a substantial rise in the number of electoral democracies (from 44 to 116) and in the number of “free countries” with firmly established constitutional limits (from 44 to 90).

Even in the current period, when democratic progress has appeared to ebb, many countries have also seen democratic resilience, including in South and Central America (such as Brazil, Chile and Mexico); Africa (Botswana, Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa); and Asia (Indonesia, Philippines and Malaysia, among others). Despite many challenges in respect to accountability and transparency, human rights and rule of law, all remain electoral democracies with governments constrained by constitutional limits.

Countries designated “free” have experienced some reduced rankings on issues of rule of law, human rights, minority rights and even basic governance (as in France in this section). Yet, such countries have strong constitutional protections of human rights, established limits on the exercise of power, and political systems with free and fair elections allowing non-violent changes in power between competing parties or blocs. Political, social, cultural and economic conflicts are resolved through constitutional means.

Among the Most Challenging Cases

As noted in Consent of the Governed, the United States has among the most challenging situations of any “Free” country. Characteristics of a democracy with constitutional limits still apply. There remain three branches of government, separation of powers, a system of federalism, a free media and basic exercise of rights. Yet, in each category, the US model has shown weaknesses. One indication is the U.S.’s rating in Freedom House’s annual survey. The United States fell nine points in the last decade, among the steepest declines of “Free” countries in this period. Only Poland and Israel had sharper drops (see Current Issues sections in the Country Studies).

[T]he United States has among the most challenging situations of any “Free” country. Characteristics of a democracy with constitutional limits still apply. There remain three branches of government, separation of powers, a system of federalism, a free media and basic exercise of rights. Yet, in each category, the US model has shown weaknesses.

Most notably, Republican Donald J. Trump challenged a number of democratic norms and constitutional limits during his first presidency. As a result, he was impeached twice in 2019 and early 2021. The first impeachment was for abusing executive power to try to subvert the presidential election in 2020. The second was for inciting a violent mob to attack the Congress to interfere with the peaceful transfer of power after he lost the election.

In both cases, the constitutional limit on abuse of power was not applied. The Senate did not convict Trump by the necessary two-thirds vote in either case due to party-line voting. Similarly, criminal prosecution of Trump for his attempt to undo a free election failed due to procedural delays and then a Republican-dominated Supreme Court’s ruling that established a new interpretation of the Constitution that presidents were largely immune from prosecution (see also subsections in Accountability and Transparency and Rule of Law ). Trump was allowed to run as the Republican Party’s 2024 presidential candidate even while convicted of felony crimes in a separate state case. In the end, voters also failed to hold Trump accountable for his prior anti-constitutional and unlawful acts and elected him to a second non-consecutive term.

Some constitutional limits showed resilience in 2020. At the state level, Republican, Democratic and independent officials across the country carried out their duties to count votes, conduct recounts and certify results despite threats of violence. Even in Republican-controlled states, elected officials refused a president’s direct requests to manipulate vote counts, deny certification of the vote and overturn certified results. Republican- and Democratic-appointed judges alike ruled on 63 filings by Trump’s campaign lawyers and determined that there was no evidence to challenge the results.

The United States has among the most challenging situations of any Free Country. Above, a mob attacks the Capitol Building on January 6, 2021 attempting to block the peaceful transfer of power. Creative Commons License. Photo by Tyler Merbler.

Still, the United States shows clear weaknesses in its system of constitutional limits. While one major party respected the peaceful transfer of power in 2025, it remains a question whether the other major political party will accept a national election loss in the future. As a candidate and as president, Trump threatened not to respect election results and aligned his party with political violence. Entering his second term in office, he immediately issued pardons or clemencies for all those convicted or who pleaded guilty in the January 6, 2020 insurrection attempt, including those convicted of seditious conspiracy. Republican members of Congress expressed little opposition to this action.

It is also unclear if the Republican majorities in the House of Representatives or Senate will exercise a check on the executive branch. Through executive orders and other actions, Trump has challenged constitutional limits. This includes ordering the end of birthright citizenship as guaranteed in the 14th Amendment; removing Inspector Generals (independent ombudsmen), federal workers and members of independent federal agencies contrary to established law; and halting expenditures as appropriated by Congress, which has the "power of the purse." There is a similar test for the judiciary. The highest court has shown recent partisan favor in its recent rulings, raising questions as to its willingness to curtail presidential abuses of power (see also Current Issues in the United States Country Study).

The content on this page was last updated on .