Summary

Map of Malaysia

The Federation of Malaysia, consisting of two territories separated by the South China Sea, is a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary system of government.

From Malaysia's independence in 1957 to 2018, the National Front dominated elections and governed in an authoritarian manner. A liberal-left opposition coalition, the Alliance of Hope, ousted the National Front in 2018 elections following corruption scandals involving top officials. In 2020, the National Front rejoined a new coalition government but Alliance of Hope again won a clear plurality in elections held in November 2022. Its long-time leader, Anwar Ibrahim, was appointed prime minister to form a new government. Scores in the Freedom in the World survey have improved since 2018, but Malaysia remains in the Partly Free category.

The Federation of Malaysia’s two main territories are West Malaysia, on the Malay Peninsula (south of Thailand) and East Malaysia on the northern part of Borneo island (the larger southern part belongs to Indonesia). Malaysia is the 65th largest country in the world by area, with 34 million people (45th largest). It has a mixed population of ethnic Malay (57 percent), other indigenous groups (12 percent), ethnic Chinese (23 percent) and Indian (7 percent).

Since the early 1980s, Malaysia has recorded impressive economic growth, largely through foreign investment in export manufacturing. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Malaysia ranked 35th in the world in 2022 in nominal Gross Domestic Product ($447 billion in total output) and 66th in nominal per capita GDP (at $13,440 per annum).

History

Early History

Malaysia's first human inhabitants date back 40,000 years. Its indigenous population today are known together as bumiputera (“people of the soil”), made up of ethnic Malay and indigenous groups of Sabah, Sarak and others on the Borneo island. Indian and Chinese traders began traveling to the region roughly 2,000 years ago, by which time indigenous political entities known as sultanates had emerged. The Indian and Chinese traders strongly influenced the population as Hinduism and Buddhism became the dominant religions.

An historical representation of a meeting of the sultan in the interior of the Malaca Sultanate Palace Museum. Creative Commons License. Photo by Azul Adnan.

Starting in the second century CE, a number of small Malay sultanates arose that relied on maritime commerce. Between the seventh and fourteenth centuries, much of the area now known as Malaysia was controlled by the Srivijaya Empire, based on the large island of Sumatra (now part of Indonesia). War with neighboring kingdoms led to the Srivijaya Empire’s decline. This strengthened competition over the lucrative trade route through the Strait of Malacca ─ the key access to the South China Sea and East Asia.

Islamic Influence, European Dominance

Around the 14th century, greater trade with the Arab world and Indian Muslims helped to spread Islam in the region, adding to the existing blend of indigenous, Hindu, and Buddhist beliefs. The state of Malacca, founded around 1400 by a local ruler and serving as a leading commercial center, adopted Islam as the official religion.

The commander Alfonso de Albuquerque expanded Portugal’s empire in the early 16th century after rounding the Cape of Good Hope to access the Indian Ocean. Among his conquests was Malacca in 1511. The Netherlands, after expanding its empire to islands that later formed Indonesia, captured the city-state in 1641. Great Britain occupied Dutch possessions during the Napoleonic wars and also established a base in Singapore in 1819 (see Country Studies).

British Control

An 1824 treaty between the British and the Netherlands divided the region roughly along the borders of modern Malaysia and Indonesia, with Great Britain controlling Malay territories on both the Malay Peninsula and Borneo. Great Britain established a network of protectorates and colonies that left the existing sultanates with varying degrees of autonomy. In 1909, the British compelled the kingdom of Siam (now Thailand) to give up control of some Malay states setting the current northern border on the Malay Peninsula.

From its other possessions, Great Britain encouraged migration of Chinese and Indian workers, who arrived in the country in larger number during the 19th and early 20th centuries and played distinct roles in the economy and society. The Chinese workers formed mining communities to extract tin and gold and later settled in towns to engage in commerce. Many Indians were imported as administrators and laborers for agricultural plantations producing cash crops like rubber. The ethnic Malay population largely remained in rural villages but also continued to dominate the state structures of the sultanates.

Postwar Insurgency

Following a brutal Japanese occupation during World War II, the Allies liberated Malay territories in 1945. Ethnic Malayan leaders and local rulers feared political disorder and welcomed the return of British administration. British colonial power, however, had weakened and Malaysia’s many ethnic and political groups had conflicting visions for the postwar order.

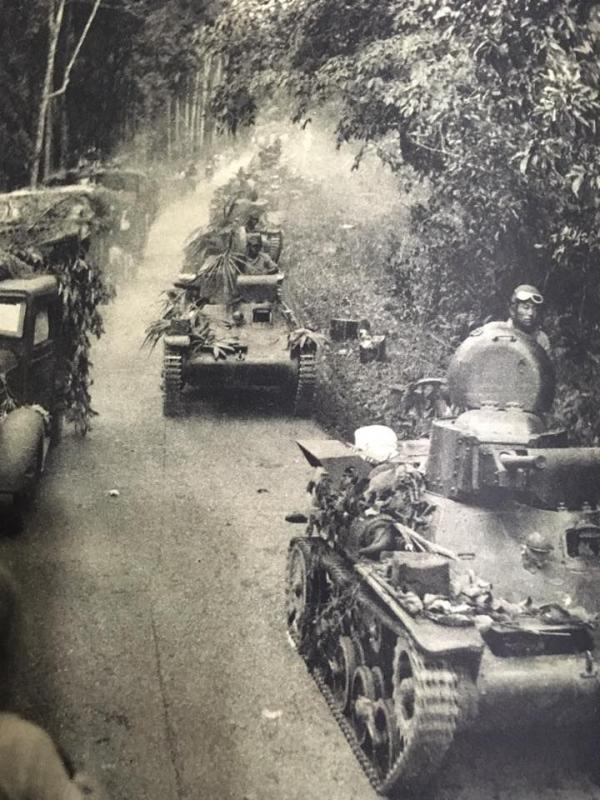

Following the brutal Japanese occupation, ethnic Malayan leaders welcomed the temporary return of British administration. Japanese troops advancing in the decisive Battle of Kampar (1941-42).

The British at first sought to create a Malayan Union to merge the peninsular states and provide equal citizenship for all ethnic groups. The United Malays National Organization (UMNO) opposed the plan hoping to preserve the political privileges of ethnic Malays. The British created the Federation of Malaya in 1948 on the Malay peninsula, leaving various other sultanates, including those on Borneo, separate.

The ethnic Chinese-dominated Communist Party of Malaya, which had fought against the Japanese and supported the initial union plan, began a decade-long insurgency that was backed by Communist China. As the British put down the rebellion, often with great brutality, the colonial authorities brokered a compromise among the non-Communist ethnic-based political parties. These included UMNO, the largest party, the Malayan Chinese Association (MCA) and the Malayan Indian Congress (MIC). The three groups formed a governing coalition known as the People’s Alliance.

Independence

At the time of the Federation of Malaya's declaration of independence in 1957, the People’s Alliance agreed that the more prosperous non-Malay ethnic groups, which played central roles in the merchant economy, would enjoy equal citizenship and cultural autonomy. The bumiputera — referring to ethnic Malays and other indigenous groups — would gain certain special privileges, especially in education and the economy.

In 1963, Singapore and the northern Borneo states of Sarawak and Sabah, until then still administered by the British, were united with Malaya to create the Federation of Malaysia. Singapore, largely ethnic Chinese in population, withdrew in 1965 to become a separate city-state (see Country Study). Within the new Federation, West Malaysia (on the Malaya peninsula) has 11 states and 2 federal territories. East Malaysia (on Borneo) has two large states and one federal territory.

Multiparty System

Malaysia has a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary system and bicameral legislature. The monarch, known formally as Paramount Ruler and informally as king, is the titular head of state. The king is chosen on a rotating basis by nine hereditary monarchies among the thirteen states. The bicameral parliament is made up of an elected People’s House (Dewan Rakyat) and a State Council (Dewan Negara), or Senate. The latter has both appointed and indirectly elected members by state legislatures.

Malaysia has a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary system and bicameral legislature.

The king nominates the prime minister after an election on the basis of who can form a majority in the People’s House (normally the leader of the party with the most seats). On the prime minister’s recommendation, the king names the government cabinet and appoints forty-four of the seventy members of the State Council, who may serve two 3-year terms. The thirteen state legislatures elect two each of the remaining twenty-six members.

The People’s House, with 222 seats, is the main law-making body. The State Council has limited powers to amend or block legislation (the king must also formally approve legislation). Members of the People’s House are elected to five-year mandates from single-member districts in a “first past the post” electoral system. There is universal suffrage with the voting age lowered to 18 in 2021.

Above, the Malaysian Houses of Parliament. The main legislative chamber, the Dewan Rakyat (People’s House), is in the middle. Creative Commons License. Photo by Pangalau.

Until 2022, the electoral system was skewed in favor of the ruling coalition, the National Front (Barisan Nasional), mostly by malapportionment favoring Malays in rural districts. Laws inherited from colonial rule were often used by National Front governments to prosecute opposition politicians.

Until 2022, the electoral system was skewed in favor of the ruling coalition, the National Front (Barisan Nasional), mostly by malapportionment favoring Malays in rural districts. Laws inherited from colonial rule were often used by National Front governments to prosecute opposition politicians and restrict freedom of association, assembly, media and speech.

The constitution guarantees religious freedom but it is violated in law and practice. All ethnic Malays must be registered as Muslim and practice Sunni Islam. Civil (non-religious) courts have ruled that individual Malays may not renounce Islam and must submit to religious courts where they have jurisdiction. Hinduism, Buddhism and other faiths face government restrictions and discrimination.

The National Front and its predecessor, the People’s Alliance, dominated elections and controlled government from Malaysia’s independence in 1957 to 2018. The coalition’s largest party is the United Malays National Organization (UMNO). In 2018, the National Front lost elections for the first time. It returned to lead the government in 2021, but lost elections again in 2022 and now serves in a minority position within a unity government (see below and Current Issues). Below is a more detailed history of Malaysia's multiparty system and how Malaysia developed into an electoral democracy.

The 1969 Race Riots and Positive Discrimination

UMNO's leadership was first challenged in elections in 1969 when the original ruling coalition, the People’s Alliance, lost ground to the opposition Democratic Action Party (DAP) and others. The DAP, drawing much of its support from the ethnic Chinese community, sought to end privileges for the bumiputera. Its rising position sparked riots by indigenous Malay in which thousands of Chinese homes and businesses were destroyed. Dozens of people were killed. In response to the riots, the government invoked emergency powers under the 1960 Internal Security Act and suspended parliament for two years. The government then adopted the New Economic Policy (NEP) to further boost development. Affirmative action and quotas were established to promote bumiputera in education, business and employment in a policy called positive discrimination.

UMNO’s Dominance

UMNO formed a broader coalition, the National Front (Barisan Nasional), which now included the United Traditional Bumiputera Party from Borneo’s Sarawak region, the traditionalist ethnic Chinese and Indian parties, and ten smaller parties. From that time, the National Front secured sweeping electoral victories and enjoyed greater than two-thirds parliamentary majorities on a platform of nationalism, state development and religious conservativism.

Mahathir bin Mohamad is the dominant political figure of post-independence Malaysia, serving as prime minister from 1981-2003 and from 2018-20. Shown here, visiting the United States in 1984. Public Domain.

In this period, Mahathir bin Mohamad became Malaysia’s dominant political figure. As prime minister from 1981 until his initial retirement in 2003, Mahathir established a centralized, repressive state and led the country towards high economic growth.

In this period, Mahathir bin Mohamad became Malaysia’s dominant political figure. As prime minister from 1981 until his initial retirement in 2003, Mahathir established a centralized, repressive state and led the country towards high economic growth. The country was among the world’s fastest developing economies. During this time, Mahathir was a leading exponent of the idea that “Asian values” favored authoritarianism.

The opposition Democratic Action Party (DAP) and Islamic Party of Malaysia (PAS) competed within restrictive and unfair conditions (including heavily gerrymandered districts favoring ethnic Malays). The two parties gained few seats in the People’s House (Dewan Rakyat), the State Council (Dewan Negara) and state legislatures.

Emergence of a Stronger Opposition

In 1998, a larger opposition movement arose after a popular deputy prime minister, Anwar Ibrahim, was dismissed by Mahathir over his criticism of cronyism and government bailouts of favored businesses during that year’s financial crisis. Anwar led a protest movement (known as Reformasi) that called for an end to corruption and greater social justice.

The government arrested Anwar for corruption and sodomy, charges widely seen as politically motivated. Awaiting trial, he created the People’s Justice Party to contest the 1999 elections and formed a united opposition with the liberal Democratic Action Party (DAP) and the conservative Islamic Party of Malaysia (PAS). The opposition won just 20 percent of seats, but it was a substantial increase on previous elections.

Protests in 1999 led by former deputy prime minister Anwar Ibrahim led to a stronger opposition but also repression. Above, Anwar is nominated by his supporters for a by-election to parliament in 2008 after spending 5 years in prison on fraudulent charges. Creative Commons License. Photo by Leonard Wan.

Anwar was subsequently sentenced to a total of nine years in prison. On appeal the sodomy conviction was overturned. A separate corruption charge was upheld and he served five years in prison.

In 1998, a larger opposition movement arose after a popular deputy prime minister, Anwar Ibrahim, was dismissed by Mahathir over his criticism of cronyism. . . . Anwar led a protest movement (known as Reformasi) that called for an end to corruption and greater social justice.

In 2003, Mahathir resigned after 23 years in power. Under his hand-picked successor, Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, the National Front reclaimed 90 percent of seats in the People’s House in elections held in 2004 due to greater government gerrymandering and other unfair electoral conditions. These included an abbreviated seven-day campaign period, dominant pro-government media coverage, and a prohibition on criticizing the ruling party.

Electoral conditions remained similarly unfair in 2008 elections, but a larger opposition coalition emerged, again led by Anwar Ibrahim. Using the same name as Malaysia’s original ruling coalition, the People’s Alliance (Pakatan Rakyat), it denied the National Front a two-thirds majority in the People’s House for the first time since independence. This meant that the National Front could no longer change the constitution or basic laws at will. The People’s Alliance also won majorities in five state legislatures. After a ban on serving office ended, Anwar himself won a by-election in a rural district.

Repression Continues

Due to the disappointing election result, Badawi stepped down as prime minister and was replaced by a deputy prime minister, Najib Razak. His father and uncle had held the post prior to Mahathir.

The government again charged Anwar Ibrahim with sodomy. In slow-moving proceedings, a lower-court conviction was reversed on appeal in January 2012. But other means were used to marginalize the opposition. Although free awaiting appeal, Anwar was suspended from parliament for insulting the prime minister. Also in 2011, the deputy president of the Islamic Party of Malaysia (PAS) was charged with defaming police officers and soldiers. (He had criticized government actions in the 1950s to combat communist guerillas.) Other opposition politicians were charged under the 1950 Sedition Act, a remnant of British colonial administration.

The Campaign for Fair Elections

After the 2008 elections, sixty-two non-governmental organizations created the Coalition for Clean and Fair Elections (Bersih) to pressure the ruling party to establish fairer conditions in future elections. Bersih organized three mass demonstrations in 2011 and 2012 that were violently dispersed by police. The home of its leader, an ethnic Indian, was attacked. Due to Bersih’s public pressure, Prime Minister Najib Razak felt compelled to offer reforms he claimed would limit government repression. In fact, they had the opposite intent and effect. Human Rights Watch concluded that the new laws “broadened police apprehension and surveillance powers.”

Another Rigged Election

The 2013 elections had a campaign period lengthened to one month but it remained dominated by state media attacks on opposition parties and candidates (such as regular broadcast of fake videos of Anwar Ibrahim in alleged compromising sexual situations). The opposition’s campaign, however, drew large support. Turnout was an unprecedented 85 percent of 13.3 million registered voters.

The Coalition for Clean and Fair Elections (Bersih) organized mass protests in 2011-12 that led to reformed election conditions. Protesters facing police in April 2012. Creative Commons License. Photo by Cumi&Ciki.

The official election results showed 51 percent of the overall national vote went to Anwar’s People’s Alliance and 47 percent to the National Front. But weighted districts favoring rural areas together with electoral fraud gave the ruling coalition a majority of 133 seats in the People’s House to 89 seats for opposition parties. Despite public testimony by Bersih members of electoral manipulation, the People’s Alliance lost all court challenges filed in 31 districts. Najib Razak remained prime minister and UNMO party chairman.

Economic Development and More Repression

After the 2013 elections, the government ordered new large economic development projects benefitting bumiputera while at the same time ordering multiple arrests of opposition leaders.

At the government’s request, the Court of Appeals in March 2014 reversed its earlier ruling vacating Anwar Ibrahim’s conviction. This barred him from his seat in parliament and from running for a state legislature seat in Selangor (his predicted victory would have propelled him to the governorship of Malaysia’s richest federal state). In a retrial in 2015, Anwar was again found guilty on the 2008 sodomy charge and sentenced to 5 years’ imprisonment.

Anwar’s lawyer was then convicted on charges of violating the Sedition Act. Eight other opposition members, including the deputy chairman of the People’s Alliance, faced similar charges. In March 2014, the leader of a new Islamist opposition party lost a defamation suit for articles implicating the Election Commission of fraud in his native Sabak region.

Incompetence and Corruption

The government, however, faced numerous challenges. Public support fell after a botched investigation into the March 2014 disappearance and presumed crash of Malaysian Airlines Flight 370 (239 passengers and crew were lost).

The corruption of Prime Minister Najib Razak led to a profound and surprising re-alignment in Malaysian politics. Speaking as prime minister in 2012. Creative Commons License. Photo by Firdaus Latif.

Major corruption scandals involving the prime minister and other top officials also dominated the news. Media revealed that $681 million dollars had been transferred into Prime Minister Najib Razak’s private bank accounts prior to the 2013 elections. It was widely suspected that the money had gone to the campaigns of UMNO politicians. But the Attorney General made a formal determination in January 2016 that no criminal investigation was warranted on the grounds that $621 million had been returned as unused to the original donor, a Saudi prince, and that the entire donation had been meant for a private building development investment. No explanation was given for how the unreturned $61 million was used. The Malaysia Anti-Corruption Commission (MACC) appealed the attorney general’s determination.

Around the same time, the Swiss government announced that it had evidence that $4 billion belonging to Malaysia’s sovereign wealth fund, 1Malaysian Development (1MDB), had been transferred into accounts controlled by the prime minister, family members and political allies. The US Justice Department subsequently filed a complaint to seize more than $1 billion in assets purchased with funds it claimed were laundered through US banks.

The corruption scandals led to a profound and surprising re-alignment in Malaysian politics over two elections, as described below.

Current Issues

Former Prime Minister Mahathir bin Mohamad, alarmed by the growing corruption in the ruling alliance, returned to public life in 2016 to call for the resignation of Najib Razak. The man who had molded a semi-authoritarian state (see above) became a surprising champion for democratic reform and rule of law. Mahathir resigned from the United Malaysian National Organization (UMNO), the largest party in the ruling National Front, or Barisan Nacional (see above). He formed the Malaysian United Indigenous Party, or Bersatu, and joined the Alliance of Hope (Pakatan Harapan), a larger coalition formed by Anwar Ibrahim’s People’s Justice Party in 2015 (see Multiparty System above).

Former Prime Minister Mahathir bin Mohamad, alarmed by the growing corruption in the ruling alliance, returned to public life in 2016. . . . The man who had molded a semi-authoritarian state became a surprising champion for democratic reform and rule of law.

With Anwar in prison, Mahathir led the Alliance of Hope in early elections held in May 2018. It won a large plurality of the vote, 45 percent to 34 percent for the National Front. Even with the existing electoral system, the People’s Alliance gained a full majority in the 222-seat People’s Assembly (Dewan Rakyat). Of the 113 seats it won, the large majority were held by Anwar’s People’s Justice Party and the long-allied Democratic Action Party. The Sabah Heritage Party (Warisan), a regional party, won an additional eight seats and allied with the People’s Alliance.

A meeting of the Dewan Rakyat (People’s House) after the April 2018 elections, which ousted the ruling National Front from power for the first time since independence. Creative Commons License. Photo by DannyG15.

Although Bersatu had won only 13 seats, the 92-year-old Mahathir returned as prime minister. Anwar’s wife, Wan Azizah, herself a popular leader of the People’s Alliance, served as deputy prime minister.

Mahathir quickly forced the Attorney General out of office. A new Attorney General resumed the high-level corruption investigations. He soon arrested and indicted Najib Razak, his deputy, and others for the diversion of large sums from 1MDB, the state development fund. Despite government upheaval (see below), the Attorney General successfully prosecuted Razak, who was convicted in May 2021 on seven counts of abuse of power and corruption. He was sentenced to twelve years in prison. (Other cases were settled out of court, including a $3.9 billion government settlement with Goldman Sachs over its involvement in the scandal.)

Mahathir bin Mohamad (left) came out of political retirement to lead the Alliance of Hope coalition to victory in the 2018 parliamentary elections against the increasingly corrupt National Front, the party he had once led. He served as Malaysia's prime minister in 2018-20. Above, he meets President Joko Widodo while in Indonesia. Public Domain.

Mahathir also requested the king to pardon his former political nemesis, Anwar Ibrahim. After his release, Anwar won a by-election in October 2018 to return to parliament. In addition, a controversial law aimed at suppressing independent media, the “Fake News Act,” was repealed. There were other reforms of the repressive legal system.

But the People’s Alliance government lasted just twenty-two months due to a leadership crisis over Mahathir’s agreement to cede the prime minister’s position to Anwar Ibrahim. Bersatu broke with its leader to leave the coalition as did the vice president of Anwar’s People’s Justice Party.

They formed a new coalition, the National Alliance, which included two traditionalist parties, the Malaysian Islamic Party and the Malaysian People’s Movement Party. It was able to form a nationalist government without a new election on the basis of support from UMNO’s deputies. Bersatu’s new president, Muhyiddin Yassin, became prime minister.

The new government did not last long. Yassin was forced to resign after one year due to his mishandling of the Covid 19 crisis. UMNO now formally joined the government to maintain a majority coalition and its vice president replaced Yassin as prime minister. This government, too, was unstable. Yassin asked the king to set early elections.

The pro-reform party of Anwar Ibrahim, twice imprisoned by the long-standing nationalist ruling party in Malaysia, won elections both in 2018 and 2022. He is now prime minster.

The national elections were held in November 2022. For the first time since independence, no coalition won a majority in the People’s House but the People’s Alliance, running on a progressive platform, won 82 of the 222 total seats with a strong plurality of 38 percent. The right-wing National Alliance, led by Bersatu’s Muhyiddin Yassin, won 32 percent of the vote and 74 seats with a sweep of Malay-dominated regions in West Malaysia. The previously dominant National Front, still led by UMNO, declined to 23 percent and just 30 seats. The other seats went to regional parties from the two East Malaysia federal states (Sarawak and Sabah) and four independents. Many leading politicians and long-time parliament members lost their seats (including Mahathir himself and Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah, known as the “father of economic development”).

The long-time opposition leader and former political prisoner, Anwar Ibrahim, was named by the king to be prime minister and asked to form a government.

Anwar proposed a unity government. UMNO’s Ismail Sabri Yaakob, who had served as prime minister from 2021-22, and other smaller parties agreed. But the new National Alliance declined and decided to go into opposition. In the meantime, state legislatures had also seen a political realignment. The People’s Alliance and National Alliance each had established majorities since the 2018 elections in most states, supplanting the National Front and UMNO. In 2023 regional state elections, this re-alignment largely held, however the nationalist Malay and Islamist parties, now in coalition, made gains in key regions, including Senghor (see article in Resources).

As leader of a diverse governing coalition, Anwar moved slowly to enact major reforms, but did succeed in achieving the repeal of the death penalty and decriminalization of attempting suicide.

• • •

Since 1998, when a stronger opposition movement emerged around a dissident politician, Malaysia’s semi-authoritarian governance system evolved from a dominant one-party system into a multi-party system with greater democratic governance. At present, a multifaceted political party system has emerged with liberal, reform, religious, conservative, nationalist, regional and ethnically based political parties representing a diverse set of interests.

The content on this page was last updated on .