Summary

Map of Estonia

Estonia, a small republic in northeastern Europe, has a parliamentary system with a unicameral (one chamber) legislature. The country re-established its independence in August 1991, breaking free from its forced incorporation into the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). Estonia today is among the world’s most free and economically dynamic countries.

Estonia has a strong national heritage based on its distinct Finno-Ugric language and Estonians’ defense against invasions starting in the first millennium CE. From the 13th to the 20th centuries, however, Estonia was dominated by German, Danish, Swedish and Russian overlords. A period of independence began in 1918 after World War I but ended at the outset of the Second World War with occupation by the USSR in 1940. This was followed by German occupation (1941–44), re-occupation by the Red Army, and Estonia’s forced incorporation into the USSR (1944–91).

During the Soviet occupation, Estonians nearly became a minority in their own country due to migration of ethnic Russians and other groups. A national democratic movement arose in the 1980s and by 1991 it had organized independent elections for an Estonian Congress and a referendum on independence. Under this pressure, the formal legislature, although elected under Soviet control, declared Estonia’s independence on August 20, 1991. As more republics asserted independence, the USSR dissolved that December.

Estonia, a small republic in northeastern Europe, has a parliamentary system with a unicameral legislature. The country re-established its independence in August 1991, breaking free from its forced incorporation into the USSR.

Estonia adopted a new constitution with full political and economic freedoms. Since 1992, it has held nine free multiparty elections for its unicameral parliament (Riigikogu in Estonian) and also nine free local and district elections. Returning to Europe, Estonia joined the EU and NATO in 2004 and has held five elections for the European parliament. It consistently earns high scores for political rights and civil liberties in the Freedom in the World survey.

Estonia has a population of just 1.3 million people. As of 2023, Estonians constitute 69 percent of the population (up from 60 percent in 1991). Ethnic Russians are 23 percent. Other nationalities (Ukrainian, Belarusian, German, Swedish, Finno-Ugric and other ethnic groups) make up 7 percent. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the nominal gross domestic product (GDP) for 2022 was $44 billion (102nd largest in the world). In nominal GDP per capita, Estonia is ranked 37th ($31,209 a year). The Heritage Foundation's 2023 Index of Economic Freedom ranks Estonia 6th of 178 countries.

History

The Crusade for Livonia

The earliest inhabitants of Estonia date to 11,000 years ago, while settlements with defensible forts are recorded as early as 1800 BCE. The first written mention of Estonians was recorded by the Roman historian Tacitus in 98 CE.

An early map showing the regions of Livonia, 1260. Creative Commons. Attribution: Termer.

Until the 12th century, Estonians lived in small communities in an area known as Livonia and developed sufficient military organization to repulse attacks from Scandinavia to the west and Slavic lands to the south and east. In 1202, however, the Livonian Order—an organization of German knights created under authority of Pope Innocent III—conquered Estonia’s southwest region.

The Livonian Order merged with the larger German Order of Teutonic Knights and gained final control of northern Estonia, bringing to power a long-lasting Germanic ruling class that reduced most of the Estonian population to serfdom. Major towns joined the Hanseatic League, an alliance of trading cities along the Baltic and North Sea coasts.

Sweden's Baltic Empire and Russian Annexation

The Tsar of All Russia, Ivan IV (“Ivan the Terrible”), invaded parts of Livonia in 1558 and defeated the Livonian branch of the Teutonic Order. As a result, southern regions of Estonia sought protection from the Polish king and the northern region sought it from Sweden’s monarchy. A series of conflicts among the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Sweden and Russia ended in Sweden’s victory and expanding its Baltic empire. By 1629, it had gained control of most of the mainland of Estonia (both north and south regions).

Sweden’s rule lasted 150 years with lasting impact. Most of the population adopted Sweden’s Lutheran religion, which remains dominant today. Swedish authorities expanded education to peasants in the Estonian language to encourage the reading of scripture and allowed Estonian in higher education.

In 1710, under Peter the Great, Russia conquered Estonia as part of a new, larger regional war against Sweden, thus ending Sweden’s empire. Peter the Great established cooperation with still-dominant German elites and overturned Swedish reforms benefitting the Estonian peasantry.

Estonia’s National Awakening

Over the 18th and 19th centuries, an Estonian intellectual and middle class grew and embraced Enlightenment ideas of national independence and liberty.

Over the 18th and 19th centuries, an Estonian intellectual and middle class grew and embraced Enlightenment ideas of national independence and liberty. A reform movement achieved abolition of serfdom in 1816–19 (well before Tsar Alexander II abolished serfdom in Russia). Land reform laws allowed peasants to move freely and buy property. By the end of the century, Estonian peasants possessed two-fifths of private land. The rise of industry also brought a larger Estonian population to towns and cities.

In the 1870s, a rising national movement promoted use of the Estonian language and development of its culture. Estonian nationalists initially allied with Russian authorities against German cultural domination but turned against the central government when Tsar Alexander II adopted a policy of Russification.

Revolution and Independence

Revolution first swept the Russian Empire in 1905. Estonians formed their first legal political parties and demanded autonomy within a new Duma (or parliament). Tsarist authorities were able to re-impose political dominance, but World War I shattered the Russian monarchy and Empire. Facing military defeat against Germany, Tsar Nicholas II abdicated in March 1917. A multinational Provisional Government was formed in St. Petersburg.

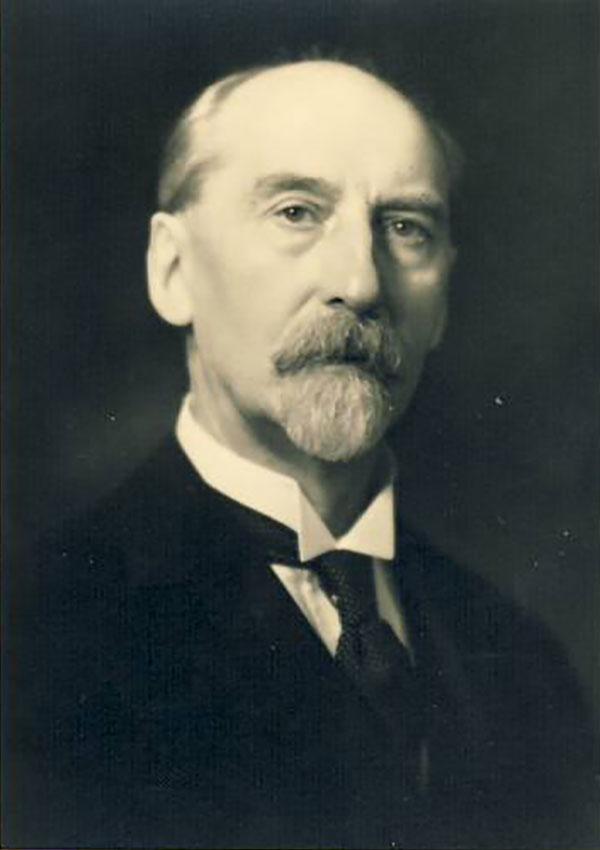

Estonia’s national awakening led to independence after World War I. Jaan Tõnisson, above, was its first prime minister in 1919-20. He also served as Staat Elder and foreign minister. Like many independence leaders, he was arrested and killed after the Soviet invasion in June 1940. Public Domain.

In Russia’s unstable political conditions, the radical Bolshevik Party seized power in November 1917 to establish the Russian Soviet Socialist Federated Republic (RSSFR). On February 24, 1918, in Tallinn, Estonia’s capital, a provisional national assembly declared independence even though Estonia was still under German occupation. Germany did not recognize the independence declaration, but upon Germany’s surrender to the Allies in November 1918, its army handed power to the Provisional Government.

An Estonian national army, aided by the Allies, repelled an attempt by the Bolshevik Red Army to impose a “soviet” regime and incorporate it into the RSSFR. The RSSFR recognized the independence of all three Baltic States (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) in the Tartu Peace Treaty of 1920.

The new Estonian government broke up the estates of the German nobility and abolished aristocratic privileges. A series of fragile coalitions governed until 1933. At that point, Konstantin Pats, the State Elder (president), dissolved the national assembly and suspended the constitution to block the Vats Party, a popular fascist movement that supported Adolf Hitler’s coming to power in Germany. The party weakened and later distanced itself from the Nazi government. Elections were held again in 1938 under a new constitution.

Soviet and German Occupations

Estonia, which was denied defense protection by Western countries, pursued a policy of neutrality. But this did not safeguard its independence. The Treaty of Nonaggression Between Germany and the Soviet Union, signed in August 1939, set the terms for the launch of World War II. Known as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, its secret protocols divided eastern Europe between the two empires. Germany attacked western Poland on September 1, 1939. The USSR, which was allotted the Baltic States, eastern Poland and other areas under the Pact, invaded Poland from the east on September 17. Estonia was occupied in June 1940 and incorporated into the USSR two months later.

The Soviet Union first occupied Estonia in June 1940 as a result of the August 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact between Nazi Germany and the USSR that divided eastern Europe between the two powers. Above, the signing of the pact by Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov. Public Domain. National Archives and Records Division.

The first Soviet occupation, lasting one year, was a period of great brutality. About 60,000 people were killed or deported. On one night alone, June 14, 1941, the Soviets deported 10,205 men, women and children to Siberia by cattle car. Most died before reaching the camps.

To fulfill his vision of lebensraum (“living space”), Hitler broke the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in June 1941. The Wehrmacht invaded the USSR as well as its eastern European-held territories. Nazi forces quickly overtook Estonia and the other Baltic states. The Nazi occupation was as brutal as the Soviet one. An estimated 7,000 Estonians suspected of Soviet collaboration were executed. Estonia's small Jewish population was targeted for extermination.

The Soviet Red Army repelled the Nazi invasion from Soviet territory starting in late 1943 and began moving westward. It re-occupied Estonia in 1944 and incorporated it back within the USSR as a Soviet republic.

The German and Soviet wartime occupations together resulted in the loss of nearly a quarter of Estonia's population. The Soviets carried out additional executions and deportations after the war and had a deliberate policy to move ethnic Russians and other nationalities into Estonia.

The German and Soviet wartime occupations together resulted in the loss of nearly a quarter of Estonia's population. The Soviets carried out additional executions and deportations after the war and had a deliberate policy to move ethnic Russians and other nationalities into Estonia. Cultural institutions were gotten rid of and the Estonian language was marginalized in education and other official institutions. Estonians, once ninety percent of the population, dropped to sixty percent by 1990. Russian speakers served in all top political, military and administrative positions.

National Renewal and the Soviet Collapse

Estonians who actively opposed communist rule were killed or imprisoned. Yet, as in the 19th century, Estonians organized to preserve their culture and language. Political dissidents pressed for human rights and independence despite the risk of imprisonment.

In the mid-1980s, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev adopted the policies of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) in an attempt to reform the USSR’s failing economy. Dissidents used these policies to launch movements for national autonomy and independence in nearly all of the USSR’s constituent republics.

In Estonia, a moderate opposition called the Popular Front advocated autonomy within a looser Soviet structure. A more determined opposition formed the Estonian National Independence Party (ENIP) to press for full independence through mass action.

On August 23, 1989, the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, independence movements in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania organized a human chain of two million people stretching across the three Baltic countries over nearly 500 miles to symbolize their people’s determination to regain statehood from illegal occupation.

On August 23, 1989, the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, two million people linked hands across the three Baltic countries over nearly 500 miles to symbolize the countries’ determination to regain statehood. Creative Commons. Photo by: L. Vasauskas.

ENIP organized citizens' committees to register prewar Estonian citizens and their descendants, who then voted in an informal election for an independent Estonian Congress in 1990 even as the Soviet legislature kept formal authority. Pressured by the Estonian Congress, the legislature declared independence in August 1991 when hardliners attempted to overthrow Gorbachev and restore Soviet power. After the coup’s failure, many other republics declared independence and the USSR disbanded in December.

International recognition of Estonia’s declaration of independence was quick, including that of the United States. (The US government had never recognized the incorporation of the Baltic States into the Soviet Union.) The period of Estonia’s regained independence is presented below.

Economic Freedom

Over the 19th century, Estonia’s national movement had won freedom for Estonian serfs, established property rights for peasants and city-dwellers, and restored the use of the Estonian language following centuries of dominance by foreign powers. When independence was achieved at the end of World War I, Estonia’s national assembly established full political and economic freedoms.

A national democratic movement arose to re-establish independence in 1991 on the basis of its previous inter-war sovereignty. . . . [T]he country restored political rights, civil liberties and economic freedom.

Soviet and German occupations during World War II ended Estonian independence and the Soviet re-occupation in 1944 incorporated Estonia as a Soviet republic within the USSR. Political and economic freedom ended. As in all Soviet republics, property was collectivized and economic activity was carried out through state planning and direction. Mass repression, both during the war-time occupations and the Soviet period, decimated Estonia’s population (more than a quarter of Estonian citizens were killed).

Like its other Baltic neighbors, Estonia survived Soviet occupation. A national democratic movement arose to re-establish independence in 1991 on the basis of its previous inter-war sovereignty. In doing so, the country restored political rights, civil liberties and economic freedom.

A Rebirth of Democracy

In June 1992, Estonia enacted a constitution by referendum that drew upon earlier versions from its inter-war period of independence. The constitution asserted the continuity of Estonian statehood and re-established a parliamentary democracy with a unicameral (one-chamber) parliament.

The 101-member legislative chamber, the Riigikogu (Ri-gi-ko-gu), is elected in proportional voting by district, with a five percent threshold for entering parliament. The D’hondt method of electoral counting is used that favors leading parties in redistribution of votes from those not meeting the threshold.

Tunne Kelam, shown above in 2010, was a long-time dissident during the Soviet occupation and founder of the Estonian National Independence Party that spearheaded Estonia’s second national renewal. He was elected the first Speaker of the restored parliament, in 1991. Creative Commons. Photo by: Avjoska.

The Riigikogu passes all laws, approves treaties and appoints all high officials, including the president as head of state, the chief justice of the Supreme Court, and the Prime Minister, who is head of government, and all government ministers. The President is head of state with limited powers.

Usually, the Prime Minister is the leader of the party that gains the most seats in parliament and is able to form a majority coalition. Since regaining independence, Estonia has held nine national elections and nine local elections (in alternate four-year cycles). Estonia also has held five elections for the European Parliament since entering the European Union.

Estonia has obligatory voting. Even so, voter turnout for the latest parliamentary elections, held in March 2023, was just 63.5 percent. Known for embracing high technology in its economy, a majority voted by internet.

The Multi-Party System and Coalition Governments

Since 1991, elections have been free and fair. The larger parties are those that evolved from the independence movement and the Popular Front — ranging from social democratic to national conservative. Between five and thirteen parties have met the threshold to be represented in parliament.

The center-right “Fatherland Bloc” won a plurality in the first elections (22 percent) and formed a broad-based government with the Estonian National Independence Party (ENIP) and the Centrist Moderates, the successor of the Popular Front. In 1995, ENIP merged with a Christian Democratic and conservative coalition to form the Pro Patria Union. In 2007, it merged again with the Res Publica Party to form the Pro Patria and Res Publica Union (IRL).

Since 1991, elections have been free and fair. The larger parties are those that evolved from the independence movement and the Popular Front — ranging from social democratic to national conservative. Between five and thirteen parties have met the threshold to be represented in parliament.

The liberal Reform Party has been the leading party since 2005. It was created out of a split in 1994 with the national conservative coalition that formed the Pro Patria Union. The Centrist Moderates was renamed themselves the Center Party. As a post-communist party, it relies largely on ethnic Russian support. A broader-based Social Democratic Party receives 10-15 percent of support.

In 2014, after nine years as Prime Minister, Reform Party leader Andrius Ansip resigned due to unfavorable poll ratings. Ansip had led the most stable period of governance in the post-1991 period. Taavi Röivas, the 34-year-old Culture Minister, replaced him and had the Reform Party switch from its usual coalition partner, the national conservative IRL, to the center-left Social Democratic Party to form a new government prior to the next election.

In the 2015 national elections, the Reform Party, Center Party and Social Democratic Parties remained near their usual levels of support. They won 30, 27 and 15 seats respectively in the 101-seat Riigikogu. But the national conservative Pro Patria and Res Publica Union (IRL), blamed for the austerity policies adopted after the financial crisis, had its worst showing (14 seats). The beneficiary of IRL’s drop in support was a new far right-wing populist party, the Conservative People’s Party (EKRE), which garnered 8 seats. It campaigned on an anti-immigrant, anti-LGBT and anti-EU platform, reflecting the rise of similar far-right parties in Europe.

Citizenship, Minority Rights And Russian Attacks

A controversial decision in the 1990s was the parliament’s adoption of citizenship and language laws. These required postwar Soviet immigrants and their descendants to apply for citizenship and meet minimum naturalization requirements (two years of residence and knowledge of Estonian, which was made the sole official language).

The law was criticized internationally for disenfranchising ethnic Russian and other Russian speaking residents but ethnic Estonians considered the requirements an essential means to strengthen a national community decimated by Soviet occupation. In the end, more than three-quarters of Russian immigrants and their descendants qualified for citizenship. Five percent of the population did not meet citizenship requirements and became stateless. While there exist anti-discrimination laws, Freedom House continues to report discrimination against the Russian-speaking minority population.

In 2007, Estonia’s internet system was shut down over two weeks by Russian digital attack in response to the Tallinn government’s relocation of the above Soviet-era monument to the “liberation” of Estonia in 1944. The relocated Bronze Soldier continues to attract Russian supporters. Creative Commons. Photo by: Lilia Moroz.

Estonia faced many public threats by the Russian Federation and a high level of disinformation directed by Russian state media. In 2007, Russia directed an attack on Estonia’s internet, shutting its system down over two weeks. The reason for the attack was the relocation of a monument from central Tallinn that celebrated the Soviet “liberation” of Estonia in 1944. The internet attack presaged military aggression by the Russian Federation against other neighboring states.

A Model Economy

The coalition government that formed following the 1992 elections instituted quick and lasting free market economic reforms under first prime minister of Estonia's re-constituted republic, Mart Laar. These reforms included privatization of state enterprises, reestablishment of private property and title rights, and a quick transformation of the legal and tax structures to conform to European Union (EU) standards. This allowed Estonia to gain EU membership in 2004 and enter the Euro zone in 2011. In 2004, Estonia also joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

In 1994, Prime Minister Laar succeeded in adopting a 26 percent flat tax for both corporate and individual income, later reduced to the current rate of 20 percent. This has been seen as a lynchpin for Estonia’s rapid economic growth.

Estonia's free-market reformers like Mart Laar were termed “radical” because they quickly transformed a Soviet economy into a capitalist one. But they are aligned with classical liberal and conservative parties in Europe. Whatever the term used, Estonia emerged as a dynamic economy and innovator of technology (Skype was among the early Estonian companies created).

Estonia’s radical transition away from the Soviet-controlled and planned economy was led by Mart Laar, prime minister of Estonia from 1992-94 after the re-establishment of independence. Shown here as leader of the Pro Patria and Res Publica Union (IRL) at a meeting of the European People’s Party. Creative Commons.

The 2007-08 world financial crisis hit Estonia harder than most countries. GDP fell 19 percent; unemployment rose to 20 percent. The coalition government, made up of the Reform Party and Pro Patria and Res Publica Union (IRL), adopted harsh austerity policies to protect against currency devaluation and keep Estonia’s schedule to join the Euro zone in 2011.

Still, Estonia maintained relative freedom from exploitation. Unlike many countries in the EU, Estonia’s income inequality has decreased since 2004. The GINI coefficient, a standard measure where 0 is perfect equality and 1 is perfect inequality, was .33 in 2021 (near the EU average). One reason is the maintenance of a basic social safety net. According to the World Bank, the poverty level, which had increased after the financial crisis, fell from 25 to 20 percent from 2016 to 2018, with a low level of extreme poverty (3 percent).

Despite the severity of the 2007-08 financial crisis, the country’s growth rate in the 1990-2014 period averaged around 15 percent. GDP grew more than four times since 1990, outpacing all former Soviet Bloc countries and propelling Estonia to the mid-level of EU countries in per capita income (projected to be $31,855 for 2024).

Current Issues

Out of the 2015 elections (see above), the liberal Reform Party joined with the Social Democratic Party (SDE) and the conservative Pro Patria and Res Publica Union (IRL) parties in an anti-populist coalition to counter the strong showings of the pro-Russian Center Party and the far-right Conservative People’s Party (EKRE). But the coalition broke apart in 2016 due to the unsteady leadership of the Liberal's young prime minister, Taavi Röivas, who was unable to pass a budget.

The IRL and SDE then joined in an unlikely coalition with the Center Party, which put the Reform Party in opposition for the first time since 2005. The coalition was made possible after Edgar Savisaar, the Center Party’s long-time post-communist leader, was ousted after being suspended as mayor of Tallinn due to corruption charges. The new leader, Jüri Ratas, had pledged to distance the Center Party from Savisaar’s pro-Russian orientation and association with Vladimir Putin’s United Russia party.

In the March 2019 elections, the Reform Party increased its share of the vote (29 percent) and the Center Party again came in second (23 percent), but the far-right EKRE party jumped to third position (18 percent). The conservative Pro Patria and Res Publica Union, which recast itself with the simpler name Isamaa (Fatherland), fell to 11 percent. The SDE dropped to 10 percent despite having gotten government increases in both the minimum wage and the tax threshold for low-income workers.

The Reform Party was unable to form a government. Instead, the Center Party formed a majority coalition with EKRE and Isamaa. This also proved an unstable alliance. EKRE members, including its leader, Mart Henne, were forced to resign from their ministries for controversial and racist statements. The Center Party became embroiled in more corruption scandals (party leaders were charged with trading government benefits for a $1 million party contribution). Center Party leader Jüri Ratas resigned as Prime Minister in January 2021.

Prime Minister Kallas emerged as one of Ukraine’s strongest supporters in Europe. Estonia provided its entire stock of US-made Javelin anti-tank missiles, which proved vital to [Ukraine's] defense after the February 2022 invasion. Estonia provided among the highest per capita levels of military and humanitarian support to Ukraine of any NATO country.

The Reform Party was again asked by the president to form a government. Its new leader. Kaja Kallas, became Estonia’s first woman prime minister by forming a narrow coalition with the Center Party. Kallas was quickly faced with the Russian Federation’s preparations for an all-out invasion of Ukraine in the summer and fall of 2021. The first consequence was an energy crisis that eased only when Kallas provided government relief for citizens’ energy costs.

With the invasion imminent, Prime Minister Kallas emerged as one of Ukraine’s strongest supporters in Europe. Estonia provided its entire stock of US-made Javelin anti-tank missiles, which proved vital to the defense of the capital Kyiv after the February 22, 2022 invasion. Estonia since has provided among the highest per capita levels of military and humanitarian support to Ukraine of any NATO country and welcomed 60,000 Ukrainian refugees for permanent status. Kallas’s actions made her Estonia’s most popular politician.

The Center Party withdrew from the government in June 2022, allowing Kallas to form a more pro-NATO cabinet with Isamaa and the Social Democratic Party (SDE). This reprised the earlier anti-populist coalition of 2015-16. In the March 2023 elections, the Reform Party increased its support to 31 percent and 37 seats, the strongest performance of any party since 1992. The Center Party and EKRE lost support, but EKRE still emerged as the second largest party (17 percent). A new liberal party, E200, came in fourth at 13 percent as SDE and Isamaa continued to fall in voter support (9 and 8 percent, respectively).

Kallas formed her third cabinet with E200 and the Social Democratic Party. Isamaa declined to join due to its opposition to a coalition pledge to legalize same sex marriage and adoption. In June 2023, Estonia became the first country in Central and Eastern Europe to do so.

Kallas was embroiled in controversy over her husband’s minority share in a transportation firm that was still doing business in Russia despite her own government’s call to end all economic activity with Russia. She remained prime minister, but her popularity declined, even more so when she and the Reform Party backed several tax increases that proved unpopular with its liberal base.

In EU parliament elections, the Reform Party lost its leading position, dropping to 18 percent. Isamaa won a surprising 21.5 percent of the vote and the Social Democratic Party came in second position at 19 percent. While EU parliament elections are not as significant as national elections, they reflect a current mood of the electorate. Kallas resigned soon after as prime minister in July 2024 after being elected the European Union’s new High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy. (It is the first time a member of the newer bloc of Central and Eastern European countries in the EU has held that post.) She was replaced as prime minister by Kristen Michal. a longstanding member of the Reform Party. He served as Minister of Climate in 2023-24 and previously as Minister of Economic Affairs.

As head of the Reform Party, Kaja Kallas led three governments as Estonia's first female prime minister from 2021 to 2024. In July 2024, she was elected the EU's High Representative Foreign Affairs. Above, she meets with US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken at the July 2023 NATO Summit in Lithuania. Public Domain.

The content on this page was last updated on .