Summary

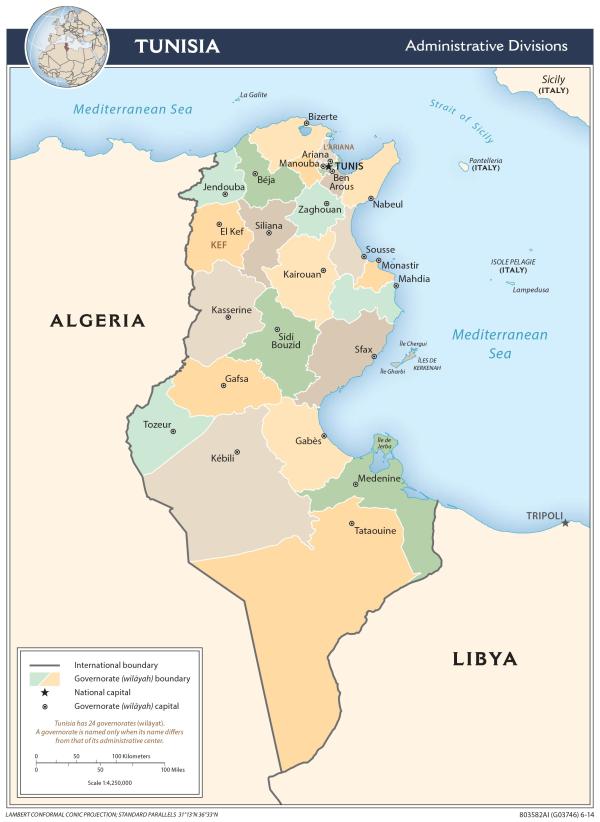

Map of Tunisia

Tunisia, a North African country on the Mediterranean Sea, is now a presidential republic following a staged constitutional referendum in 2022. Its president has used repression to end the country’s short-lived parliamentary democracy.

Tunisia was peopled from around 4000 BCE by Amazigh (also known as Berber) communities. Starting from the 1st millennium BCE, Tunisian territory experienced successive Phoenician, Roman, Arab and Ottoman conquests. In the late 19th century CE, as part of Europe’s “race for empire,” France made it a colony. Tunisia gained independence from France in 1956, after which it was governed for 55 years by two secular authoritarian rulers.

In January 2011, the second of Tunisia’s authoritarian rulers, President Ben Ali, fled to Saudi Arabia following a popular uprising known as the “Jasmine Revolution.” Tunisia’s protest movement sparked the Arab Spring, a broader revolt against dictatorships across the Middle East and North Africa.

Of all the Arab countries, Tunisia had the only real transition to democracy, at least for a time. An interim government oversaw a constitutional referendum. Two free and fair general elections followed. But that success ended in 2021, when a newly elected president suspended parliament, repressed political opposition and directed a constitutional overhaul to solidify presidential rule (see Current Issues).

Tunisia’s trade union movement has played an important role in its modern history, from its national independence movement to the Jasmine Revolution, and then in helping to mediate a constitutional compromise. Tunisia’s free trade union federation now opposes the current government.

Tunisia’s protest movement sparked the Arab Spring, a broader revolt against dictatorships across the Middle East and North Africa. Of all the Arab countries, Tunisia had the only real transition to democracy, at least for a time.

Tunisia is a small country located between Algeria and Libya on the North African coast. It is ranked 91st in the world in area (161,600 sq. km.) and 78th in population (12.5 million people in 2023). Ninety-eight percent of its population identifies ethnically as Arab and religiously as Sunni Muslim. A center of agriculture and commerce, Tunisia is a middle-income country. In 2023, the International Monetary Fund ranked Tunisia 92nd in the world in nominal Gross Domestic Product (GDP) at $51 billion in total output and 122nd in GDP per capita at $4,191 per annum.

History

From Ancient to Modern Times

Like Morocco (see Country Study), the territory of Tunisia was inhabited as long ago as 4000 BCE by nomadic tribes who came to be known as Amazigh (also referred to in English as Berber). Between 1000-800 BCE, Phoenicians expanded their trading empire from the eastern Mediterranean to the North African coast. The most important city founded was Carthage in Tunisia.

Like Morocco . . . the territory of Tunisia was inhabited as long ago as 4000 BCE by nomadic tribes who came to be known as Amazigh (also referred to in English as Berber).

Ancient Carthage emerged as its own empire and nearly defeated Rome in the Punic Wars (265-146 BCE) before being rebuffed and then defeated. The city was razed in 146 BCE by the Roman army, but the Roman Empire made the province its African stronghold until its own collapse in the 5th century CE.

In the 7th and 8th centuries CE, Tunisia’s territory was one of the Arab Islamic conquests and the population was largely converted to Islam. Tunisia thrived under Arab Caliphates and different Arab-Berber dynasties. Its capital Tunis remained an intellectual and economic center after the Ottoman Empire took military control in the mid-16th century.

Tunisia gained autonomy under the Ottoman Beys (imperial governors), but in 1881 the French government forced the Ottoman Empire to cede the country as a protectorate. Under Arab, Turkish and French control alike, Tunisia was governed mostly by elite classes of foreigners. Amazigh tribes, with their own language, culture and customs, were left behind economically.

Independence Leads to 55 Years of Dictatorship

In the period between World Wars I and II, indigenous Tunisians began demanding local representation, then autonomy and finally independence. The movement for national independence was launched with the formation of Neo Destour (New Constitutional Liberal Party) in 1934 and grew stronger after the Allied defeat of Axis forces in the Africa Campaign that liberated Tunisia during World War II.

The movement for national independence was launched with the formation of Neo Destour (New Constitutional Liberal Party) in 1934. The French government negotiated a transition to independence in 1955.

France’s post-war administration repressed the independence movement but was more focused on maintaining colonial rule in neighboring Algeria. Under pressure from Tunisian independence forces, especially the independent labor movement, the French government negotiated a transition to independence in 1955 (see also Freedom of Association below).

Elections held in 1956 were won by Neo Destour, led by Habib Bourguiba. A new constitution was adopted centralizing powers in the presidency. Bourguiba, elected president, quickly established a one-party dictatorship. In 1975, he had himself declared President-for-Life. Ruling with varying degrees of harshness, Bourguiba professed himself a pro-Western secular modernist in opposition to pan-Arabism and Islamic fundamentalism, the two political movements prevalent in the region.

In 1987, Bourguiba, suffering from dementia, was declared unfit and replaced in a bloodless coup by the prime minister, Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. Initially, Ben Ali undertook some liberalization. He freed political prisoners, allowed multiple parties to run in elections and renamed Neo Destour to Democratic Constitutional Party (RCD) to distinguish it from Bourguiba’s time of rule.

Under Ben-Ali, Tunisia became one of the world’s least free states. Political opposition was repressed and the ruling party and Ben Ali continued to claim 90 percent of the vote in staged elections.

Liberalization stopped, however, when the Islamic Renaissance Movement threatened the RCD’s dominance. Despite the former gaining clear support during the 1989 election campaign, the RCD claimed an implausible 90 percent of the vote. The government banned all Islamist parties, arrested 8,000 followers of Islamic Renaissance and re-imposed censorship.

Under Ben-Ali, Tunisia became one of the world’s least free states. Political opposition was repressed and the ruling party and Ben Ali continued to claim 90 percent of the vote in staged parliamentary and presidential elections. Ben Ali still generally allied with Western states and fostered secular policies, such as advancing women’s rights. Education was extended to a broad sector of the society, including girls. But his economic policies left Tunisia undeveloped while the country’s wealth was concentrated in a loyal elite.

Tunisian independence led to 55 years of dictatorship of varying harshness, first under Habib Bourguiba and after 1986 under Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. Tunisia under Ben Ali became one of the world’s least free states. Above, Ben Ali posters for staged presidential elections in 2009. Creative Commons. Photo by Chris Barr.

The Arab Spring

After more than 30 years in power, Ben Ali ran for a fifth term in 2009. He immediately prepared to run for a sixth term by having a rubber-stamp parliament adopt a constitutional amendment to allow it.

[I]n mid-December 2010, an unemployed university graduate, Mohamed Bouazizi, trying to make a living as a fruit vendor, set himself on fire in a protest against ongoing police intimidation. As news of the tragedy spread . . . [a] nationwide protest movement erupted.

By 2010, however, increasing civic and political resistance to the regime was evident. Local and regional branches of the trade union federation asserted greater autonomy (see also below), as did civic and student movements that had survived the regime’s repression. In response, Ben Ali had the rubber-stamp parliament pass a law criminalizing civic and political opposition.

Then, in mid-December 2010, an unemployed university graduate, Mohamed Bouazizi, trying to make a living as a fruit vendor, set himself on fire in a protest against ongoing police intimidation. As news of the tragedy spread, the self-immolation became a symbol for the population’s frustration with government repression and corruption. Nationwide protests erupted and intensified when Bouazizi died of burn wounds on January 5, 2011.

The police used force daily against demonstrations demanding the ouster of the government in Tunis, the capital, and in other large cities. Nevertheless, the protests grew larger as trade union and student movements declared their support. A total of 219 people were killed. Over that time, army backing for the government weakened and army leadership signaled reluctance to continue using force. On January 14, 2011, less than a month after the start of the non-violent protest movement, Ben Ali fled to Saudi Arabia.

Ben Ali’s prime minister declared a new government, but it was made up mainly of regime loyalists. Protests resumed until the prime minister resigned and the government of holdovers fell. This began the Arab Spring’s only successful transition to democracy — for a time. The success and then failure of Tunisia’s democratic transition is told in more detail in the Freedom of Association and Current Issues sections.

In December 2010-January 2011, Tunisian protestors launched the Arab Spring. The month of mass protests had a simple message, “Ben Ali Dégage” (or “Ben Ali Go Away”). The Tunisian dictator fled to Saudi Arabia. Public Domain.

Freedom of Association

Freedom of association was not widely practiced prior to French colonial administration. But in the colonial period, independent trade unions, civic organizations and political parties developed to a surprising degree. The free trade union movement played a central role in achieving independence.

Freedom of association was not widely practiced prior to French colonial administration. But in the colonial period, independent trade unions, civic organizations and political parties developed to a surprising degree. The free trade union movement played a central role in achieving independence.

In fifty-five years of dictatorship after independence (1956-2010), opposition political parties were repressed. Tunisian trade unions and some civic organizations retained a measure of independence but did not act as political opposition. That independence allowed the Tunisia General Workers Union (UGTT) to join with other student and civic organizations in playing a key role in the Jasmine Revolution (see above). The UGTT then contributed to mediating the conflict between religious and secular political parties that stalled the democratic transition to achieve real change.

While Tunisia took an authoritarian turn in 2021, it stands apart among Arab and North African neighbors as a country where freedom of association had a strong and lasting impact in bringing about national independence and democracy. The history of Tunisia’s trade union movement is told below along with its role and that of civil society generally in the democratic transition. Its role since the suspension of parliament by the president is described in Current Issues.

Colonial Period and Struggle for Independence

The Tunisian labor movement started to develop under French colonial administration at the turn of the century. Trade union development slowed after the colonial administration repressed protests for the right to strike in 1924. But French domestic pressure, particularly by its own labor movement, prompted the administration to codify a right to organize unions in 1932.

Tunisian unions were influenced by French political and labor movements. Most new unions aligned with the communist-dominated General Confederation of Workers (CGT). But the rigid stance against independence taken by the French Communist Party and its Tunisian labor branch prompted a nationalist trade union leader, Farhat Hached, to break with the CGT in 1946. He organized new unions and united with others to form a new federation called the Tunisia General Workers Union, or UGTT (its acronym in French).

[T]he rigid stance against independence taken by the French Communist Party and its Tunisian labor branch prompted a nationalist trade union leader, Farhat Hached, to break [ties] in 1946. He organized . . . a new federation called the Tunisia General Workers Union.

Hached was elected the federation’s General Secretary and convinced the UGTT to join the non-communist International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU). By doing so, he gained international renown and support for the UGTT’s militant unionism and its position for national independence.

When the French colonial administration carried out a harsh crackdown in 1952 on Tunisia’s nationalist Neo Destour party, Hached became the main leader of the independence movement. The colonial administration responded by arresting 20,000 of the UGTT’s members. A French paramilitary organization called “The Red Hand” assassinated several UGTT leaders, including Hached himself.

Hached’s assassination sparked large protests throughout North Africa and Europe that successfully pressured the French government to ease its repressive policy and begin negotiations for independence with the Neo Destour party and its leader, Habib Bourguiba (see History above).

Farhat Hached formed the Tunisia General Workers Union and played a leading role in the independence movement. Above, center (in suit and tie), Hached leads a labor march in the capital, Tunis. His assassination in 1952 sparked region-wide protests. Public Domain.

The UGTT During Dictatorship

After Tunisia achieved independence in 1956, the UGTT initially had a close relationship to the new government, which even adopted several core conventions of the International Labor Organization.

[T]he UGTT had a diverse and independent network of regional and workplace structures defending the basic right of freedom of association and representing workers at the local level.

President Bourguiba, however, began to repress the UGTT when its branches organized local strikes over the government’s economic and wage policies. In 1978, Bourguiba ordered force against a national strike organized by the UGTT. A period of trade union repression led the UGTT leadership to back the 1987 bloodless coup of Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. The new leader’s initial liberalization earned further cooperation by the trade union movement.

Trade union repression soon resumed, however. While the UGTT remained the only mass independent organization in Tunisia, its national leadership often submitted to government policies to ensure the federation’s survival. Even so, with 300,000 to 500,000 members, the UGTT had a diverse and independent network of regional and workplace structures defending the basic right of freedom of association and representing workers at the local level. Some leaders, however, advocated a more militant stance and broke from the labor federation to create a rival, called CGTT. While small, it successfully pressed the UGTT to take a greater opposition role. Independent civic associations also arose, such as a lawyers association defending those whose human rights were violated.

The Role of Trade Unions in the Arab Spring

In keeping with its history, the UGTT federation became the leading social force supporting secular political parties and development of civil society. Overall, thousands of new civic organizations began operating after the revolution.

In December 2010, as the response grew to Mohamed Bouazizi’s self-immolation (see History above), local UGTT and CGTT trade unionists mobilized members to take the lead in anti-government demonstrations. Local union offices were headquarters for the uprising around the country. Pressed from below, the more compromising national UGTT leadership had to withdraw from the first transition government (which was dominated by Ben Ali loyalists). When a congress of the UGTT was held a few months later, new leaders were elected who supported a genuine democratic transition.

In keeping with its history, the UGTT federation became the leading social force supporting secular political parties and development of civil society. Overall, thousands of new civic organizations began operating after the revolution.

The Transition Begins

When the holdover cabinet resigned in March 2011 as a result of further protests, eighty-five year-old Béji Caïd Essebsi, a respected former foreign minister known for his reform efforts, was named as prime minister. He crafted an independent transition government and directed an expansion of political freedoms and civil liberties. Newly assertive courts dissolved Ben Ali’s Democratic Constitutional Party. The High Court tried Ben Ali and his wife in absentia for state theft. Both were sentenced to 35 years’ imprisonment.

Media and civil society organizations exercised their new freedoms. A range of secular and Islamist political parties organized to compete in elections for a National Constituent Assembly. In October 2011 elections, Ennahda (Renaissance), an Islamist party representing moderate to conservative viewpoints, won a plurality of 37.5 percent of the vote. Several secular parties divided the vote but received nearly 50 percent total. Fundamentalist Islamist parties and independents split the remaining 15 percent.

Ennahda formed a government with the two largest secular parties, the liberal Congress for the Republic (CPR) and the Democratic Forum for Labor and Liberties (Ettakatol), a social democratic party. The three parties divided the positions of prime minister, president and head of the National Constituent Assembly, respectively. The government consisted mostly of former political prisoners or dissidents returning from forced exile.

Transition Debate and Delay

The National Constituent Assembly (NCA) began a prolonged debate over the drafting of a new constitution. As it did so, the UGTT trade union federation and civil society groups held national dialogues. Positions of the main political factions were reported in newly independent media. At root of the debate was the role of religion in government. Ennahda wanted to introduce religious principles directly into the constitution and government’s practices. Non-religious parties and civil society groups resisted these efforts in defense of Tunisia’s secular traditions.

At root of the debate was the role of religion in government. Ennahda wanted to introduce religious principles directly into the constitution and government’s practices. Non-religious parties and civil society groups resisted these efforts in defense of Tunisia’s secular traditions.

The debate took place amid rising political violence by religious extremists. A movement of Salafists, representing a fundamentalist sect of Islam, organized attacks on alcohol venders, women not wearing Islamic dress and a range of secular targets. These included the UGTT headquarters and the US Embassy. In February 2013, a known opponent of Islamism was assassinated, sparking national protests demanding an end to the religious violence. The prime minister resigned and was replaced by the Interior Minister, who acted to try to shut down Salafist bases.

Ennahda (Renaissance), however, continued to insist on religious provisions in the constitution, such as a blasphemy law, which was opposed by the journalists’ union, and declaring Sharia the basis of Tunisian law. In response, the UGTT helped to organize the National Dialogue Congress composed of 50 parties and civic organizations to advocate for a more secular constitution guaranteeing basic rights.

In response to rising public frustration over continued political deadlock, Ennahda’s founder and leader, Rached Ghannouchi, decided to direct the party to drop the demand for a blasphemy law and to compromise on the constitutional framework for a mixed presidential system. In July 2013, however, another assassination of a secular party leader re-awakened public fears of religious violence and the dominance of Islamist parties in politics. The UGTT itself organized major demonstrations in the summer of 2013. Tensions rose further as the main secular opposition party, Nidaa Tounes (Call for Tunisia), demanded the government’s resignation and holding new elections.

UGTT leader Houcine Abassi (far left), formed the National Dialogue Quartet with three civil society leaders to mediate a deadlock over the draft constitution. They were awarded the 2015 Nobel Peace Prize for steering Tunisia’s leaders towards a democratic outcome. Creative Commons. Photo by Bundesministeriums für europäische und internationale Angelegenheiten.

Ending the Deadlock

The Secretary General of the UGTT, Houcine Abassi, decided to step into this breach to form the National Dialogue Quartet to propose mediating a political agreement. It included the leaders of the Tunisian Confederation of Industry, the Tunisian Order of Lawyers and the Tunisian Human Rights League. The governing parties accepted the Quartet’s road map for dialogue. Ennahda and Call for Tunisia leaders met in Paris to come to a National Dialogue Agreement, which was signed by all parties. Under the agreement, an interim government was formed while final provisions of the constitution would be resolved within the existing National Constitutional Assembly.

One unresolved issue that represented Tunisia’s political impasse between religious and secular parties was over the definition of the state in the preamble. In the end, a compromise was reached. The preamble begins:

“Tunisia is a free, independent and sovereign state, Islam is her religion, Arabic her language, and republic her [form of] government.”

It then states:

“Tunisia is a state of civil character, based on citizenship, the will of the people, and the primacy of law.”

A mixed presidential-parliamentary system was established with guarantees included for freedoms of expression, assembly, association and religion. . . .

The new constitution was approved on January 26, 2014 by the National Constituent Assembly, with final amendments made in February. Elections were scheduled for later that year. A mixed presidential-parliamentary system was established with guarantees included for freedoms of expression, assembly, association and religion. Many Ennahda members objected that Sharia was not declared the basis of Tunisian law. But Ghannouchi and other Ennahda leaders had concluded that the party would lose support by continued deadlock over an issue that divided the country.

For helping to resolve Tunisia’s political crisis and ensuring a peaceful path towards democracy, the National Dialogue Quartet was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2015.

The First Free Elections

The National Dialogue Agreement mandated the appointment of a neutral Independent High Authority for Elections, which prepared a consensus electoral law passed in May by the National Constituent Assembly. The law included a gender equity provision, unusual for the Middle East but also for the world, that mandated alternating male and female candidates on party lists. As importantly, it set fair conditions for election administration.

The [electoral] law included a gender equity provision, unusual for the Middle East but also for the world, that mandated alternating male and female candidates on party lists.

Elections were held in October 2014 for a unicameral parliamentary chamber (called the Assembly of the Representatives of the People) with 217 seats total. Members were elected from multimember constituencies, with sixty-seven percent of the eligible electorate participating. Indicating the continued political divisions in society, the secular Nidaa Tounes (Call for Tunisia) won a plurality with 38 percent of the vote and 86 seats. Ennahda (Renaissance) came in second at 28 percent and 69 seats. Thirteen other parties also won seats.

In the presidential elections, Béji Caïd Essebsi, the 87-year-old leader of Call for Tunisia, won with 55 percent of the vote in a run-off election against presiding National Assembly President Moncef Marzouki, the leader of the liberal Congress for the Republic.

A New, if Unstable Beginning

Three secular parties won enough seats to form a majority government with Call for Tunisia. But to establish greater unity, an independent prime minister was agreed upon with Ennahda.

The new parliament’s term began in January 2015. Economic and security issues dominated. There was continued extremist violence. In response, the government again invoked a state of emergency and even ordered nightly curfews in January 2016. Among economic issues, youth unemployment stood at 33 percent. Youth protests were frequent in cities throughout the country.

Stability eluded the new government. Twenty-two left-wing members broke with the establishment wing of Call for Tunisia led by President Essebsi’s son. Ennahda became the leading party in the Assembly of Representatives. Amid continuing security threats and a faltering economy, the independent prime minister supported by Call for Tunisia and Ennahda lost a vote of confidence. A unity government of Ennahda, Call for Tunisia, five smaller parties, and two ministers close to the Tunisian General Labor Union (UGTT) took office.

For the next two-and-a-half years, there remained political divisions in addressing security issues, economic pressures (youth unemployment soared to 50 percent), transitional justice and the failure to establish a Constitutional Court. Progress was made towards establishing an independent judiciary and approval of a system for elections to local councils. A High Judicial Council was appointed. Municipal elections were also successfully held in 2018 (Ennahda gained a leading position in many local councils).

Rached Ghannouchi, who played a key role in the democratic transition as leader of Ennahda, a moderate Islamist party, addresses the party’s 2014 conference ahead of free elections for the National Assembly. He was arrested nearly a decade later in 2023 by a new authoritarian government. Creative Commons. Photo by Parti Mouvement Ennahda.

A Second Election Brings Warning Signs

President Essebsi died in July 2019 at the age of ninety-two. Under terms of the constitution, a snap presidential election was called for September. In the first round, a constitutional law professor and political outsider, Kaïs Saïed, won 18 percent of the vote. In the second round held the following month, Saïed won a landslide victory with 73 percent against the candidate of the now-fractured Call for Tunisia party.

In parliamentary elections held in October 2019, the declining trust in political parties was also apparent. Ennahda dropped eight points to just 20 percent of the vote (gaining 52 of the 217 seats). Heart of Tunisia (the largest faction of the fractured Call for Tunisia party) dropped to 15 percent (38 seats). A new progressive party, Democratic Current and a secular coalition called Dignity, each took 6 percent (22 and 21 seats respectively). Eleven other parties and seventeen independent candidates filled the Assembly of Representatives.

In February 2020, Ennahda pieced together a coalition of religious and secular parties, but the government lasted just a short time. Amid the Covid-19 pandemic, the prime minister was pressed to resign for self-dealing in public contracts. Asserting presidential powers, President Saïed appointed an independent to head the government.

Current Issues

Over a decade, Tunisia undertook what seemed to be a successful, if difficult, transition from dictatorship to democracy. The success was, in large part, due to its free and independent associations. Unfortunately, in 2021, that transition took an authoritarian turn backwards.

Over a decade, Tunisia undertook what seemed to be a successful, if difficult, transition from dictatorship to democracy. The success was, in large part, due to its free and independent associations. Unfortunately, in 2021, that transition took an authoritarian turn backwards.

With rising dissatisfaction due to an economic freefall from Covid 19 measures, large-scale protests broke out in July 2021 that took a violent turn. Ennahda’s offices were burned. President Saïed, without any consultation with parliament as required under the Constitution, invoked Article 80 to exercise emergency powers.

In fact, President Saïed exercised full authoritarian power, seemingly with support from a public impatient at democratic institutions to solve urgent problems. He suspended parliament and appointed a new prime minister, Tunisia’s first female prime leader. When the parliament attempted to meet virtually, Saïed ordered the parliament dissolved.

Saïed then ordered a new constitutional drafting process to institute a fully presidential system. A new constitution was put to a public vote in July 2022. By then, the president had lost public support. With most political parties urging a boycott, only 31 percent of eligible voters participated.

Under the new approved charter, President Saïed scheduled elections for a new bicameral legislature for December 2022 to be overseen by an Electoral Council controlled by him. Most political parties, now joined together in an opposition coalition called the National Salvation Front, again called for a boycott.

This time, there was just 11 percent turnout. A second round had to be held under special constitutional provisions to fill the seats of the new bicameral legislature, a 161-member National Assembly and a National Council of Regions and Districts. Again, only 11 percent of eligible voters participated.

President Kaïs Saïed, seen above in a 2020 meeting with USAID Administrator Mark Green, soon after his election as president. The next year, he took Tunisia on an authoritarian path by dissolving parliament and orchestrating a new constitution. Public Domain.

Starting in 2022, President Saïed actively repressed political opposition. Police arrested high-profile party leaders and hundreds of civic, political and trade union activists. Among them was Rached Ghannouchi, the previous speaker of parliament and head of the leading party, Ennahda (Renaissance). To carry out such repression, Saïed unilaterally took over Tunisia’s incipient independent judiciary. He suspended the High Judicial Council and dismissed all 57 judges it had appointed.

Using a frequent tactic of “populist” leaders, President Saïed tried to direct public anger at African migrants as well as Black Tunisian citizens, claiming in a February 2023 public speech that migration posed a threat to Tunisia’s “demographic makeup.” Since the speech, there has been widespread dispossession of Black Tunisians and violence directed at migrants. One thousand migrants were expelled and left stranded in the Libyan desert.

The Tunisian General Labor Union (UGTT) has strongly criticized President Saïed for the extraordinary constitutional process and conduct of elections. It organized strikes against the austerity terms of an International Monetary Fund loan that the president pursued to bolster his economic policy.

In the broad area of freedom of association, President Saïed has acted to try to de-register many civic organizations. Still, Tunisia continues to have a vibrant civil society and media.

The role of Tunisia’s trade union movement remains unique in the region. Its UGTT labor federation has championed secular freedoms in the midst of violent attacks by religious extremists. . . . [It helped] bring about a brief period of democracy. And today, it forms the largest civil society organization in opposition to the current authoritarian president.

The international community, including the United States, did not impose sanctions to protest President Saïed’s suspension of parliament and further authoritarian moves. The European Union, more concerned about getting the Tunisian government to help control the flow of migrants to Europe, provided stabilization funds without any conditions for returning to democratic norms.

Saïed failed to improve economic conditions and the early public support he had has weakened, which is indicated in the low turnout for elections and referenda. A united political opposition formed demanding the restoration of democracy. But President Saïed continued to consolidate power. He imprisoned the most significant opposition party leaders and barred them from running in the presidential election. In this way, Saïed ensured his re-election in the fall of 2024 to another four-year term.

The role of Tunisia’s labor movement remains unique in the region. Its UGTT labor federation has championed secular freedoms in the midst of violent attacks by religious extremists. In the transition from dictatorship, it led a mediation process among rivals in a tense political standoff to bring about a brief period of democracy. And today, it forms the largest civil society organization in opposition to the current authoritarian president.

The content on this page was last updated on .