Ancient Athens and the Roman Republic

A depiction of an early Roman assembly (the Comitia Curiate). Its assemblies voted for all officials responsible for public administration.

Athenian democracy from the sixth to fourth centuries BCE established civilian oversight of public services, public funds and the wealth and incomes of elected figures. The assembly of citizens elected officials annually (they included 10 generals, naval architects, treasurers and superintendents of the water supply). In between, they were subject to examination and recall.

More: citizens were put in charge of most public affairs. “To a degree that is amazing to the modern mind, the Athenians kept the management of their public life in the hands of the ordinary citizen,” writes historian Donald Kagan. Citizen participation was required. Auditors, financial controllers of the treasury, city commissioners, judges and jurors were chosen each year by lot. From ensuring that dung was properly disposed outside city walls, to monitoring the weights and measures of goods sold, to deciding matters of contractual dispute in courts, citizens participated in the city-state’s affairs.

“To a degree that is amazing to the modern mind, the Athenians kept the management of their public life in the hands of the ordinary citizen,”

In the Roman Republic from the sixth to first centuries BCE, its different assemblies chose all the officials responsible for public administration. There were twenty quaestors who oversaw collection of taxes and public finances. This was the first of a series of offices that characterized a career of public service. These included aediles, who oversaw public events, praetors, who oversaw courts, and tribunes and consuls, who held sovereign positions in directing Rome’s affairs. All were elected positions.

Both systems of administration and accountability, and particularly Athenian democracy, stood in stark contrast to nearly all other governments in the ancient world, most of which were despotic and marked by arbitrary rule, personal enrichment and self-aggrandizement.

Two Basic Precedents

A depiction of Martin Luther nailing his “Ninety-Five Theses on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences” at the University of Wittenberg in 1517.

In England, the Magna Carta, which was signed in 1215 CE, introduced a standard of accountability in governance for modern politics. Among other things, it obliged the monarch, King John, to accept the principle that taxes should not be raised for war without approval. Out of this agreement grew a stable form of constitutional monarchy and, over centuries, a parliament asserted greater and greater powers over public expenditures and governance (see also History in Constitutional Limits).

Another significant modern precedent was set in 1517 when Martin Luther, a doctor of theology at the University of Wittenberg, presented his “Ninety-Five Theses on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences.” Luther challenged the practice of Catholic priests selling indulgences (absolution from eternal punishment) for sins. Selling indulgences was a long-standing practice, approved by Popes, that enriched and empowered both the clergy and the Church proper. In challenging indulgences, Luther claimed the right of believers to demand accountability from temporal religious authority. Pope Pius VI ended the practice of indulgences in 1567, but not before the rise of the Reformation, a schism in Christianity between Catholicism and Protestantism.

These precedents are the basis for two basic principles: that there should not be taxation without representation (used by American colonists to assert their independence) and that officials of any governing authority should not abuse their power to extract unjust payments from citizens or members.

Embedded in the Constitution

With the rise of representative democracy in the United States, accountability and transparency became broader in scope. As an expression of the people's will, government would be more accountable to all of the country's citizens and not just to the wealthy or propertied.

Most importantly, the US Constitution set regular elections. There are federal elections every two years for the entire House of Representatives (to two-year terms) and the Senate (to six-year terms with one-third of the Senate elected in each two-year cycle). The House of Representatives was established initially to have one representative for every 30,000 residents. Since 1913, the number of representatives has been fixed at 435 with the number formally capped by legislation in 1929. The number of persons represented has increased greatly with the country’s total population with one representative on average for around 760,000 voters. (There are three one-district states with less population and four one-district states with higher population. One non-voting delegate each represent the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and four other US territories: American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands and Virgin Islands.)

Every state has two senators each, with now 100 senators for 50 states. Two national officers, the president and vice president, are elected every four years by an Electoral College. Federal elections have taken place without interruption since ratification of the Constitution in 1788. All elected representatives must swear an oath of allegiance to the Constitution

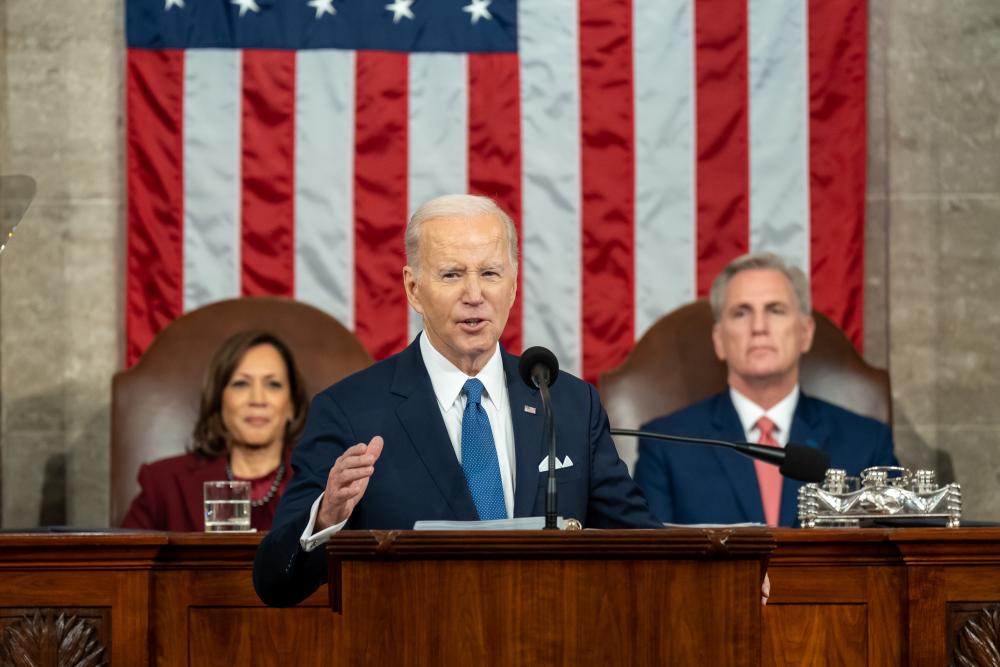

The Constitution requires the president to report annually on the “State of the Union.” Joseph R. Biden delivers the 2023 address to Congress. House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (right) and Vice President Kamala Harris (President of the Senate) preside.

With the rise of representative democracy in the United States, accountability and transparency became broader in scope. As an expression of the people's will, government would be more accountable to all of the country's citizens and not just to the wealthy or propertied.

Addressing prior abuses of monarchies, one provision in the constitution banned gifts (or “emoluments) to any officials under the United States (including all civil servants and military officers). Another prohibited the state’s confiscation of landed property without proper cause or compensation.

The Constitution required transparency to the public. The legislative branch must publish all laws and proceedings (the origin of the Congressional Record). The president must report annually to Congress (the origin of the annual State of the Union address). The executive branch must account for government expenditures (the origin of the Treasury Department’s annual Financial Report). These provisions have been followed since the meeting of the First Congress and inauguration of the first president.

The Power to Impeach

In the United States, with fixed terms in office, there is no possibility for “votes of confidence” to hold a government accountable in between election terms, as in parliamentary systems. Instead, the House of Representatives was given the power to impeach national officials (equal to an indictment) and the Senate the power to try and either acquit or convict and remove from office.

Since 1789, three of forty-five presidents were impeached. . . . Only twenty members of Congress ─ out of a total of more than 11,500 who have served ─ have ever been expelled. The House of Representative has impeached only one Supreme Court Justice, in 1804, who was acquitted.

This power is for cases of "treason, bribery or other high crimes and misdemeanors." National officials include the president, vice president and “civil officers” (meaning those approved by the Senate, including Cabinet members, ambassadors and federal judges). While impeachment in the House is by majority vote, conviction in the Senate must be by two-thirds vote. Each chamber of Congress has the power to remove its own members, also by two-thirds vote. The House and Senate also have the power to expel their own members for malfeasance, again by the high bar of two-thirds vote.

These levers of accountability have had limited use. Since 1789, three of forty-five presidents were impeached. All were acquitted and stayed in office. One other president resigned due to an impending impeachment (see below). Only twenty members of Congress ─ out of a total of more than 11,500 who have served ─ have ever been expelled. Seventeen of these were in 1861-62 for supporting rebellion against the United States. The House of Representative has impeached only one Supreme Court Justice, in 1804, who was acquitted, and 15 federal judges, all of whom were convicted by the Senate.

Until 2024, just one Cabinet officer had been impeached and tried, in 1876, but after he had already resigned (he was acquitted). In 2024, the Secretary of Homeland Security, Alejandro Mayorkas, was impeached by the House of Representatives by a majority of one vote but the proceeding was dismissed without trial by the Senate for lack of basis. Only twenty-one members of Congress ─ out of a total of more than 11,500 who have served ─ have ever been expelled. Seventeen of these (three Representatives and fourteen Senators) were expelled in 1861-62 for supporting rebellion against the United States. The most recent, George Santos, was expelled in December 2023 for fraud and corruption in campaign finances.

The Example of Watergate

The first impeachment of a president was in 1868 over President Andrew Johnson’s defiance of Congress during the Reconstruction period. He was acquitted one vote short of the two-thirds needed to convict. In 1998, Bill Clinton was impeached on charges of perjury and obstruction of justice stemming from investigation of a marital affair. He was acquitted on the first charge by a majority of 55 Senators and on the second charge by 50 Senators.

One case of impeachment resulted in a president’s resignation. This was in relation to the Watergate crisis of 1972-74, considered until recently the most significant example of abuse of power in the United States.

One case of impeachment resulted in a president’s resignation. This was in relation to the Watergate crisis of 1972-74, considered until recently the most significant example of abuse of power in the United States.

The crisis began in 1972 when reporters from The Washington Post connected payments from the re-election campaign of Republican President Richard Nixon to five burglars caught in a break-in at Washington, DC’s Watergate building complex (giving the scandal its name). The burglars were caught planting listening devices at the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee. Subsequent investigations by independent media, a special Senate committee, and a special prosecutor appointed by the Department of Justice revealed a broad conspiracy of Nixon, his staff and his re-election campaign to commit and cover up various crimes to punish political enemies, undermine opposition to his re-election in 1972, and thus subvert the democratic process.

The House Judiciary Committee held hearings in the Watergate scandal and recommended impeachment of President Richard Nixon on three charges. Barbara Jordan, foreground, was a freshman member on the Committee.

The Judiciary Committee of the House of Representatives held hearings in 1974 and recommended impeachment on three charges: obstruction of justice, abuse of power and contempt of Congress. A unanimous Supreme Court decision forced the president to release secret tape recordings that revealed Nixon's complicity in both the cover-up and other crimes. Mounting public and political pressure convinced Nixon to resign that August before facing a full impeachment vote and likely conviction in a Senate trial. In total, forty-eight staff and associates were convicted of crimes, but Nixon himself never faced criminal charges. He was quickly pardoned by his successor, President Gerald R. Ford.

The public investigation of Nixon and his resignation were seen both domestically and internationally as an affirmation of American democracy. Nixon’s pardon, however, set a precedent for not holding all citizens to the rule of law

Constitutional limits, congressional oversight, the rule of law, public opinion and the free press acted to hold a president accountable in a serious case of abuse of power. Notably, the free press had been strengthened in its role by two recent decisions of the Supreme Court: New York Times v. Sullivan (1964) and The Pentagon Papers Case (1971). These established protection for the media's rights to publish information about officials, to obtain information from government sources and to print materials that the government kept secret from the public (see also Freedom of Expression).

The public investigation of Nixon and his resignation, along with convictions of top staff, were seen both domestically and internationally as an affirmation of American democracy. Nixon’s pardon, however, set a precedent for not holding all citizens to the rule of law (see below).

Watergate and Church-Pike Reforms

The Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), passed in 1966, had given citizens and the press the right to request information from the executive branch, making government more open to public view. The Watergate crisis in 1972-74 and two related Congressional investigations of the nation’s intelligence agencies in 1975-76 (the Church and Pike Committees) showed the need for additional accountability and transparency laws.

The Watergate crisis in 1972-74 and two related Congressional investigations of the nation’s intelligence agencies in 1975-76 showed the need for additional accountability and transparency laws.

The Watergate scandal had revealed Nixon’s use of the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Central Intelligence Agency in committing crimes. As a result, two Congressional Committees were formed in 1975-76 to investigate more fully the spying on American citizens and other illegal actions by the FBI and CIA. They were known informally as the Church and Pike Committees for their respective Senate and House chairmen. This led Congress to pass the Foreign Service Intelligence Act (1978), which limited monitoring of American citizens except by a special court order based on proper cause. The Act also established special oversight committees in the House and the Senate for the nation’s intelligence and law enforcement agencies.

The Ethics in Government Act (also passed in 1978) establishes standards of honest behavior by public officials, such as requiring disclosure of income and assets by public officials and limiting gifts (thus enforcing the Emoluments Clause in the Constitution). Another 1978 law established Inspector General offices in Cabinet agencies to investigate complaints of improper behavior and to supervise government activities and spending. The Civil Service Reform Act includes protections for whistleblowers of federal employees; another law protects whistleblowers who are government contractors.

Recent Challenges

Among democracies, the United States has seen among the most serious challenges to accountability and transparency principles in recent times.

The 2008-2009 financial crisis, which led to the Great Recession and massive housing foreclosures, exposed illegal predatory practices by lending institutions. Large government bail-outs of major banks were required. Congress passed legislation (the Dodd-Frank Act) and established a new agency (the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau) to prevent a repeat of such practices. But no corporate official was held criminally responsible for actions that put the entire financial system at risk and the world in recession.

As a result [of the Citizens’ United decision], there are few limits on spending by private corporations, organizations and individuals to affect elections, laws and public decisions. This makes the United States an outlier among major democracies.

A second challenge involves the Supreme Court’s 2011 Citizens’ United decision, which struck down provisions of an election finance law (the 2002 Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act) that limited outside spending in politics.

As a result, there are few limits on spending by private corporations, organizations and individuals to affect elections, laws and public decisions. This makes the United States an outlier among major democracies. The lack of spending limits in elections or lobbying activities has given rise to serious questions about accountability and transparency in all three branches of government (see also Free Elections).

Under a second Trump administration, for example, many of its appointees are from the top 1 percent of earners, including thirteen billionaires. The person directing an "efficiency" initiative spent $250 million dollars in support of the Trump campaign and oversees federal government agencies that themselves oversee his multibillion dollar contracts with the government.

As well, the legislature now has a high proportion of its members as multi-millionaires, while both parties and most members accept support from Political Action Committees funded by wealthy individuals and corporations. Recently, exposure of unreported payments to Supreme Court Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito by billionaire political donors and a law firm having business before the Court raised concerns over the Court’s lack of enforceable ethical guidelines (see also Current Issues in the United State County Study).

A President Without Precedent

The presidency of Donald J. Trump gave rise to the most serious abuses of power in US history ─ surpassing the Watergate scandal.

Among other things, a Special Counsel of the US Department of Justice (DOJ) carried out a two-year investigation of Russia’s unprecedented interference in the 2016 election and its relationship to the Trump campaign. The investigation led to six convictions of campaign staff on various charges as well as indictments of 35 Russian individuals and entities for election interference. The report of Special Counsel Robert Mueller concluded that the Trump campaign did not formally collude with the Russian government for its support but detailed dozens of direct contacts by campaign staff with Russian agents and operatives and stated that the campaign “solicited, welcomed and used” Russia’s assistance in the election (see link in Resources). The Mueller Report also described twelve efforts by Trump to obstruct the investigation as president. However, no actions were taken by Congress or the DOJ to hold Trump accountable. He subsequently pardoned all of the campaign and administration officials who were convicted or pleaded guilty as a result of the investigation.

Separately, Trump was impeached two times by Congress ─ unprecedented in US history both in number and the scope of the charges.

Separately, the House of Representatives brought impeachment charges against Trump two times ─ unprecedented in US history both in number and the scope of the charges.

In the first case, Trump was charged with abuse of power and obstruction of Congress for attempting to manipulate the 2020 presidential election process. Specifically, he was charged with withholding Congressionally mandated military aid to Ukraine, an ally and a country at war with Russia, in order to extort its president, Volodymyr Zelensky. Trump withheld the aid and orchestrated a political pressure campaign for Zelensky to publicly announce false corruption investigations of his main political opponent, Democrat Joseph Biden. Zelensky refused at first but nearly succumbed to the demand when the scheme was thwarted by a whistleblower’s public exposure.

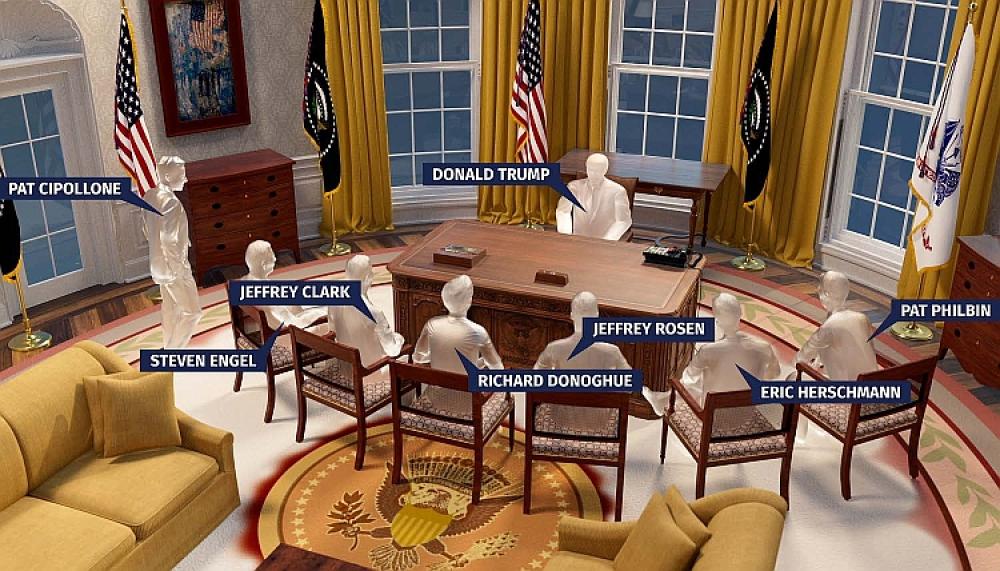

The January 6 Special Committee issued an 845-page report detailing a “multi-part conspiracy to overturn the results of the 2020 election." An illustration showing a meeting of President Donald Trump pressuring Department of Justice officials.

In the second case, the House of Representatives voted to impeach Trump for “incitement of insurrection” on January 6, 2021 in order to stop the peaceful transfer of power after losing his re-election bid to Biden. Trump had called a protest rally for that day and incited a mob attack on the Capitol that stopped the formal proceeding certifying the vote (see also subsection in Consent of the Governed).

The Senate acquitted Trump in both impeachment trials. (In the second trial, a majority of Senators, 57-43 voted for conviction but still ten votes short of the two-thirds requirement.) Under the Constitution, a conviction would have barred Trump from holding any future office. The acquittals allowed him to run for the presidency again. Trump won the Republican Party nomination in its 2024 primaries even though criminal charges were brought in one federal indictment and one state indictment for attempting to overthrow the 2020 election (see below). In November 2024, voters, acting largely on concerns over the economy and immigration, also did not hold Trump accountable. By a narrow margin, Trump was elected to a second non-consecutive term.

President Donald Trump was impeached twice, the second time in early 2021 for "incitement of [the January 6] insurrection." Above, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi signs the article of impeachment on January 13 in front of the House impeachment managers.

Weaknesses in Accountability

Notwithstanding the example of Richard Nixon in the Watergate scandal (see above), the presidency of Donald Trump shows basic weaknesses in the US system of accountability in confronting abuses of power compared to other major democracies (see below). These weaknesses include the unwillingness of elected leaders to impeach and convict a sitting president from the same party; the president’s unchecked pardon power to exonerate crimes committed at his behest; the Constitutional allowance to run for and win the nation’s highest office while under indictment or convicted of crimes. As well, procedural delays and partisan control of the courts made a president effectively immune from criminal prosecution (see also Current Issues in US Country Study).

There was an 18-month investigation, including 11 public hearings, related to the January 6 attack on the Capitol by a special committee of the House of Representatives. It found that Trump’s actions on and before that day constituted “a multipart plan to overturn the results” of the 2020 presidential election. The report stated this was the first time in the history of the United States a president had abused his powers to remain in office. The January 6 Committee made a formal referral to the Department of Justice recommending criminal indictments for contempt of Congress, obstruction of justice and incitement to insurrection (see Resources for a link to the House Select Committee Report on the January 6 Attack on the United States Capitol).

Notwithstanding the example of Richard Nixon in the Watergate scandal, the presidency of Donald Trump shows basic weaknesses in the US system of accountability in confronting abuses of power compared to other major democracies.

Donald Trump subsequently was indicted on criminal charges in four cases — one local, one state and two federal cases — again a first in US history.

First, separate from the January 6 investigation, a special counsel appointed by the Department of Justice in November 2022 indicted Trump in June and August 2023 on charges of obstruction of justice and espionage for retaining classified documents after leaving office. After many procedural delays, the case was suddenly dismissed in July 2024 by a Trump-appointed District Judge on grounds that appointments of Special Counsels are unconstitutional. Her ruling ignored decades of legal precedent upholding the practice.

The Special Counsel also indicted Trump in August 2023 on four felony charges for “criminal efforts to overturn the 2020 presidential election and maintain power” (see Resources for a link to the indictment). In the same month, the Fulton County District Attorney in Georgia indicted Trump and 18 others on racketeering charges for trying to overturn the vote in that state. (Four other states indicted Republican officials and Trump’s lawyers for attempting to corrupt the counting of the 2020 Electoral College votes. Those cases are pending.)

Trump appealed the federal case on a claim of “total immunity” for presidents even if they “crossed the line.” District and appellate courts rejected the claim, but in July 2024 the six Republican-appointed justices of the Supreme Court, including three appointed by Trump himself, made a novel ruling that presidents have absolute or presumed immunity up to “the outer perimeter” of their official duties. One dissenting justice wrote that the ruling was “a paradigm shift” in the Constitution; another that it effectively made the president “a king above the law.” The decision meant the federal case was not heard before the November 2024 election. After Trump’s narrow victory, the court dismissed the federal case without prejudice (meaning it can be brought again) the Special Counsel’s request due to a policy of not prosecuting sitting presidents. The state case is still pending but unlikely to proceed.

New York state and local courts proved slightly more effective in holding Trump accountable. In a case brought by the Manhattan District Attorney, a 12-person jury found Trump guilty on 34 felony counts of illegally disguising election expenses as business payments (see Resources on teaching students civics lessons in the case). The district court judge confirmed the verdict in January 10, 2025, making Trump the first convicted felon to serve as US president. However, due to the unusual circumstances, the judge imposed no punishment in an unconditional discharge. Separately, a New York state court found the Trump Organization guilty of business fraud. It was fined $452 million in a civil judgement. In two other civil trials, juries found that Trump committed sexual assault and was therefore liable for $84 million in damages for defaming E. Jean Carrol. (Trump had repeatedly claimed she lied when making public the assault.) None of these court judgements precluded Trump from running for president again. Each are pending appeal.

Beyond the United States

The above sections focused on historical strengths and present weaknesses in the United States for holding public officials accountable. Many established democracies ─ whether presidential, parliamentary or mixed systems ─ have shown greater consistency in observing basic principles of accountability described in Essential Principles. These include: separation of powers, protections for media, anti-corruption statutes, sunshine laws, legislative oversight, auditing agencies, civic watchdog organizations, among others. All are used to hold even the highest elected leaders to account.

Now, accountability and transparency laws are basic qualifications for membership in both the Council of Europe and the European Union.

While such mechanisms were not robust in the early development of modern democracies, Western European countries adopted strong domestic legislation for accountability and transparency after the cataclysm of World War II. Now, accountability and transparency laws are basic qualifications for membership in both the Council of Europe and the European Union.

These standards go beyond Europe. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, an inter-governmental organization of 38 democracies with free market economies, also adopted accountability standards and proposes legislation in relation to corporations, nonprofit organizations and trade unions. The United Kingdom’s comprehensive freedom of information legislation for the public sector is seen as a model (see Resources).

Among many world leaders who have been held accountable, Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi was expelled from office by the Italian Senate after being found guilty of tax fraud and sentenced to four years’ imprisonment.

Recent examples of leaders in European countries being held to account due to media exposés, criminal investigation and government oversight include:

- an Italian prime minister (Silvio Berlusconi) forced to resign and subsequently convicted of tax fraud and other charges;

- a British prime minister (Boris Johnson) forced to resign for violating Covid pandemic restrictions he had imposed;

- the Netherlands government being forced to resign due to its withholding of public assistance to eligible immigrants and citizens (see Current Issues in Country Study);

- two recent presidents of France (Jacques Chirac and Nikolas Sarkozy) convicted of violating bribery and election laws, respectively (see Current Issues in Country Study);

- a president of South Africa was forced to resign in 2018 for state corruption (see Current Issues in Country Study); and

- a president of South Korea was impeached in December 2024 for his illegal attempt to impose martial law.

In the most analogous case to the presidency of Donald Trump, former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro has been barred from running for public office until 2030 and faces indictment for accepting foreign bribes and for directing an effort to carry out a coup after losing the October 2022 election.

These cases (and earlier ones) show that most established democracies have ongoing challenges of corruption and abuse of power, but also that many have successfully held leaders accountable.

Important Factors in World Events

Corruption and the lack of accountability for abuses of power have been key factors in world-changing events. One example is the Philippines in 1986 (see Country Study in this section). "People Power" was the term used to describe the hundreds of thousands of protestors who forced their longtime ruler, Ferdinand Marcos, to resign over rampant corruption, abuse of power and an attempt to steal an election.

The People Power movement in the Philippines is an example of how corruption and abuse of power led to world-changing events. Demonstrators in Manilla in 1986 protesting President Marcos’s impunity for a massacre.

More recently, corruption and attempts to manipulate elections were significant issues in recent elections in Malaysia and Guatemala (see Country Studies) as well as in successful popular uprisings against authoritarian governments in Serbia (2000), Georgia (in 2003) and Ukraine (in both 2004 and 2013-14). In these countries and others, the public's disgust at corruption and abuse of power was a factor for mobilizing the citizenry to demand democratic change.

Corruption and the lack of accountability for abuses of power have been key factors in world-changing events.

The achievement of accountability and transparency in newer democracies is mixed. Many introduced standards of accountability and mechanisms for dealing with corruption and abuse of power. For example, this was an early achievement of Botswana (the Free country in this section) and South Africa (the Free Country in Consent of the Governed). Yet, as seen in their Country Studies, each have recent cases of corruption and abuses of power have challenged their democracies.

Other newer democracies have struggled with overcoming corrupt practices and abuses of power. In some, such as Turkey under the presidency of Recep Tayyip Erdogan, they are becoming entrenched features. These “backsliding” democracies are on trajectories to become full dictatorships, where corruption and abuse of power become systemic.

International Accountability

As noted in Essential Principles, there are few instances in history of accountability for the larger crimes of aggression, war crimes or crimes against humanity, including for slavery and genocide.

Indeed, these terms were not fully adopted as applicable international standards until after World War II with the establishment of the Nuremburg Tribunal and the Tokyo War Crimes Trials. These tribunals held accountable individuals who had carried out the unprecedented violence and killing in World War II, including the crime of the Holocaust, the organized murder of 6 million Jews by the Nazi regime in an attempt to exterminate European Jewry (see also Essential Principles).

[T]here are few instances in history of accountability for the larger crimes of aggression, war crimes or crimes against humanity, including for slavery and genocide.

Nuremburg trial principles and the adoption in 1948 of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide codified such crimes in international law and provided that states and individuals must be held accountable for committing them.

Few actions for accountability were taken until the 1990s, when the United Nations established special tribunals for the former Yugoslavia in 1993 and for Rwanda in 1994. In both cases, leading perpetrators were arrested and convicted for crimes of genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in these countries. (In the case of Serbia, the most leading figure, Slobodan Milosevic, died before his trial was completed and no finding was made.) Additional tribunals were established for Sierra Leone, Lebanon, Cambodia and East Timor.

These Special Tribunals were an impetus for establishing the International Criminal Court (ICC) in 2002. (One of the lead prosecutors in the Nuremburg Trials, Ben Ferencz, had lobbied for its creation since the late 1950s. See link in Resources.) There was now a single institution to investigate and prosecute these and other violations of international law in member countries. There are currently 123 member signatory states. (The United States is not a signatory.)

Accountability for the Past

Accountability for crimes of past regimes has been difficult to attain when pursued within countries. South Africa established a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to reveal the human rights abuses committed by the apartheid regime. But this resulted in amnesty for perpetrators who revealed their crimes to the public and few cases were pursued of others who hid their crimes. A National Commission for Truth and Reconciliation established in Chile issued a report on human rights crimes of the Augusto Pinochet regime but Pinochet and most other perpetrators of crimes escaped prosecution.

No such commissions were established following the collapse of communist regimes in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. In Poland, former leader General Wojciech Jaruzelski evaded a court proceeding on criminal charges for crimes committed while suppressing the Solidarity movement in the 1980s (see Country Study). Poland and other countries have established museums and other institutions for the examination and study of the crimes of totalitarian regimes.

In Guatemala, two former leaders were prosecuted and convicted for genocide and crimes against humanity for the mass slaughter committed in anti-insurgency campaigns in 1982-83. It was the first time a domestic court held accountable a former leader for such crimes. However, the 2013 convictions were quickly overturned by Guatemala’s Supreme Court under government pressure. In the end, prosecutions for both individuals were unsuccessful (see Country Study).

Accountability for the Present

The International Criminal Court (ICC) has jurisdiction for signatories to the Rome Convention and its cases have focused particularly on Africa, most of whose countries signed the treaty. The first sitting leader to be indicted for genocide by the ICC was Omar al-Bashir of Sudan (see Country Study), but he has yet to be extradited to face trial.

An urgent case is that of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine and genocide and war crimes committed by its armed forces and mercenaries on Ukrainian territory.

Two ongoing cases of genocide ─ that of the Rohingya in Burma and the Uyghurs in China ─ are outside the ICC’s jurisdiction.

An urgent case is that of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine and genocide and war crimes committed by its armed forces and mercenaries on Ukrainian territory. The ICC has asserted jurisdiction with the approval of the Ukrainian government (which is not a member of the ICC but formally accepted its jurisdiction).

In March 2023, the ICC indicted Russian Federation President Vladimir Putin and Maria Lvova-Belova, the Presidential Commissioner for Human Rights, for forcibly abducting thousands of Ukrainian children from war zones and taking them to Russia for permanent residence. This is considered an act aimed at eradicating a nation or culture under the Genocide Convention. Additional cases of war crimes and crimes against humanity are pending ICC investigation. On their own, domestic Ukrainian courts are carrying out investigations and trials of soldiers committing war crimes. (There are 128,498 cases documented as of May 2024. By February 2024, eighty Russian soldiers, fifteen in captivity, had been convicted of war crimes.)

The Rome Convention does not include the crime of aggression within the ICC’s jurisdiction. The EU’s European Commission, however, voted in March 2023 to establish The International Center for the Prosecution of Crimes of Aggression against Ukraine (ICPA). It opened an office in The Hague in July to pursue prosecution for the crime of aggression ─ the first time since the Nuremburg and Tokyo War Crimes Trials. Ukraine continues to call for such a body to be authorized more broadly by the United Nations.

The ICC prosecutor also brought an indictment for genocide against two leaders of the Hamas terrorist organization (since killed) for its brutal October 7, 2023 attack on Israel killing 1,200 people. He also indicted Israel’s prime minister and defense minister for war crimes and crimes against humanity for their specific roles in the conduct of the war in Gaza that has resulted in more than 40,000 deaths of Palestinians, many of them women and children. South Africa, joined by other states, submitted a case of genocide before another UN tribunal, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in the Hague, for Israel’s conduct of its war in Gaza. The ICJ has yet to rule on the matter.

The content on this page was last updated on .