Summary

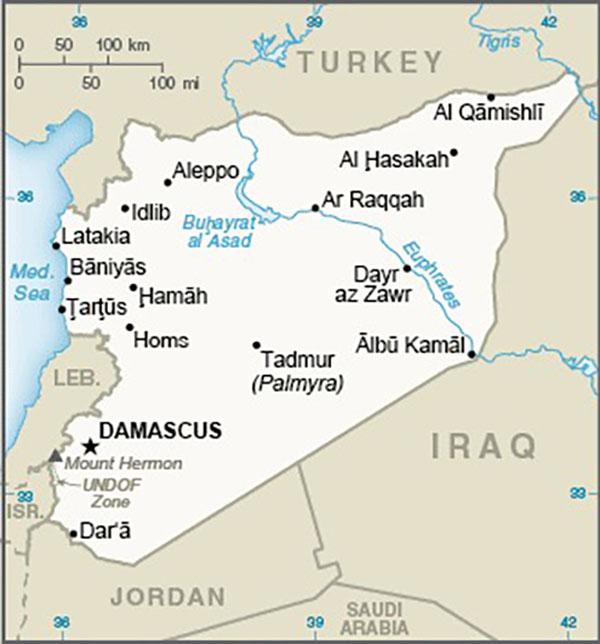

Map of Syria

Until December 2024, Syria, a constitutional republic located in the Middle East, was among the world’s most repressive dictatorships for more than 50 years. Formally called the Syrian Arab Republic, the country has had Freedom House’s lowest Freedom Rating of any country (together with South Sudan).

Syrian territory was a central pathway of ancient civilizations, conquered by Hittites, Persians, Greeks and Romans. Subsequently, it was ruled by Persian, Arab, Turkic, Mongol and Ottoman empires. Following World War I and the Ottoman Empire's fall, Syria was under French administration according to a League of Nations mandate. It gained independence in 1944. Since a 1970 coup, Syria has been ruled dictatorially by the Assad family dynasty. The government dominates political, social, and economic life. Military and security forces repress all dissent through mass imprisonment and torture.

In response to a peaceful mass protest movement in 2011, state security forces acted with brutal force, provoking an armed uprising against the regime. Rebel armies initially seized significant territory, but today the Syrian government, with the aid of the Russian military, has regained control of most of the country. Military and police forces used indiscriminate force against civilians, including use of chemical weapons, in fighting with guerilla armies.

At least 570,000 people were killed as a result of the civil war, 90 percent by government forces. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) listed 6.9 million internally displaced people (IDPs) and 5.3 million refugees in 2023, mostly in Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan. Many of the country’s cities and much of its ancient heritage has been destroyed. After 13 years of armed civil conflict, an Islamist rebel army carried out a surprising offensive in late December 2024 that toppled the Baathist regime of Bashar al Assad. The Syrian people celebrated the fall of the regime, but it was unclear what system of government would emerge in the war-torn country.

Syria is the 89th largest country in the world by area. Situated on the Mediterranean Sea, it is bordered to the north by Turkey, to the south by Lebanon, Israel, and Jordan, and to the east by Iraq and Iran. The official population estimate in 2023 was 23 million people, but this includes refugees outside its borders. Seventy-four percent are classified as Sunni Muslim (including Arabs, Kurds, Turkmen, Assyrians, Chechens and Circassians). Thirteen percent are Shi’a, mostly the mystical Alawite sect, but also others. Ten percent are Christian and 3 percent are Druze, a minority Arab group with poly-confessional beliefs.

In 2010, before the uprising, the International Monetary Fund ranked Syria 110th out of 180 countries and territories in GDP per capita at about $5,200 per annum. Its economy has fallen significantly but there are few measurements of current figures. In 2021-22, the World Bank ranked Syria 140th in nominal GDP (at $18 billion in total output) and 190th in GDP per capita (at $421 USD), among the lowest in the world.

History

From Early to Modern History

Syria's capital, Damascus, is one of the world’s oldest continuously inhabited cities, dating to at least the ninth millennium BCE. Home to a long succession of ancient city-states and empires, the territory of Syria stood at the crossroads of civilizations. Persians, coming from farther east in what is now Iran, conquered the entire region in the sixth century BCE. Two centuries later, they were displaced by Alexander the Great and his successors.

The Roman Empire took control of Syria in the first century BCE. In the seventh century CE, the Arab conquests led to the population’s adoption of Islam. Damascus served as the capital of the Muslim world in its first century, under the Umayyad caliphate, but it lost prominence when the Baghdad-based Abbasid caliphate gained ascendancy in 750 CE. The region experienced periods of both prosperity and disorder over the following centuries. There were migrations of Turks from Central Asia, Christian and Mongol invasions, as well as Egyptian domination. The Turkish Ottoman Empire conquered Syria in 1516 and maintained control over the territory until 1918.

Damascus, Syria’s capital, is one of the world’s oldest continuously inhabited cities. Above, a depiction in a Venetian painting of a Mamluk governor of the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century greeting European ambassadors at the entrance to the old city.

From Colonialism to Early Independence

Syria's current history dates to the fall of the Ottoman Empire, which had allied with Germany in World War I. Prince Faisal of the Hashemite family had led British-backed Arab forces out of the Arabian Peninsula in fighting Ottoman troops during the war. His forces entered Damascus in 1918 and established an Arab kingdom there, even as French troops occupied the coast.

Against the will of Arab nationalists, the League of Nations in 1920 established administrative mandates dividing the entire region between Great Britain (controlling Palestine, Transjordan, and Iraq) and France (controlling Syria and Lebanon). France squelched Faisal's new state in Syria. Nationalist unrest continued, however, and French officials took grudging steps toward granting Syrian independence in the inter-war period.

Syrians demonstrate in support of National Bloc leaders before they traveled to meet with the French government about independence. After elections held under Free French Army administration, Syria gained independence in 1944.

At the outset of World War II, after France fell to Nazi Germany in 1940, Syria came under administration by the French collaborationist Vichy regime. When British and Free French forces captured the territory in 1941, steps toward independence accelerated. Elections were held in 1943 and the Republic of Syria received international recognition in 1944. It joined the United Nations in 1945. French forces fully evacuated Syria the next year.

Unstable civilian rule and Syria’s defeat by the new state of Israel in 1948 led to a series of military coups in 1949, 1951 and 1954. As part of the pan-Arab movement, Syria joined Egypt in 1958 to form the United Arab Republic (UAR). Syrian leaders chafed under the domination of Egyptian president Gamal Abdul Nasser and the country withdrew from the UAR in 1961 to establish the Syrian Arab Republic. During the Cold War, Syria aligned itself with the Soviet Union.

The Ba'ath Coup and the Assad Family Dynasty

By ruthlessly suppressing political opponents and dissent, Assad remained in power for thirty years until his death in 2000, ending the pattern of frequent coups since independence.

After Syrian independence was re-established in 1961, a series of coups ended in 1963 with the restoration to power of the Ba'ath (Renaissance) Party. Espousing both socialism and Arab nationalism, it had led the 1961 break with Egypt. (A Ba'ath Party also came to power in Iraq.)

The Minister of Defense, Hafez al-Assad, seized power in 1970 from rival Ba’ath factions after a disastrous military intervention was ordered against Jordan in 1970. He drew support from his own minority Alawite sect, a mystical branch of Shi’a Islam. By ruthlessly suppressing political opponents and dissent, Assad remained in power for thirty years until his death in 2000, ending the pattern of frequent coups since independence.

The most significant challenge to Hafez al-Assad’s rule was an Islamist uprising by Sunni adherents of the Muslim Brotherhood in the city of Hama in 1982. Assad put down the rebellion with a fierce military attack that left an estimated 20,000 people dead.

In a dynastic succession, Bashar al-Assad, the middle son of Hafez, replaced his late father as president in 2000. (The eldest brother had died in a car accident.) Bashar’s younger brother, Maher, became commander of Syria’s Republican Guard. He oversees a feared security force.

Intervention and Regional Alliances

Ba'athist Syria initially positioned itself as the champion of Arab nationalism and the Palestinian cause against Israel. Syria was a major participant in all the Arab wars against Israel (1948, 1967 and 1973). Under the Ba’athist regime, it also hosted Palestinian terrorist organizations on its territory. But when it backed Iran in the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq war, the Syrian government harmed its relations with Arab states and its standing as an Arab leader. Iran’s government continues to be a key ally of Syria’s leadership.

Syria has been ruled since 1970 by Hafez al-Assad (front) and his second oldest son, Bashar (back row, second left), since 1970. Bashar succeeded his father as president in 2000. The family portrait is from 1994.

Syria’s main strategic interest in the region is neighboring Lebanon. In 1976, Syria intervened in Lebanon’s civil war, a conflict among ethnic and religious factions that had broken out the year before. Over the next three decades, even after fighting subsided, Syria’s troops and intelligence agents remained in the country. After 1985, Syria also supported Hezbollah, a Shi’a-dominated terrorist organization that arose after Israel’s invasion of southern Lebanon.

Syria withdrew its forces from Lebanon in 2005 due to international and Lebanese outcry over its involvement in the assassination of Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq al-Hariri, a Sunni Muslim politician who had opposed the Syrian presence. Syria still interfered in Lebanese politics through Hezbollah. (Although also implicated in the Hariri assassination, Hezbollah’s political arm took part in forming subsequent governments.)

Multiparty System

There was no multiparty system in Syria during the 57-year rule of Hafez al-Assad and his son Bashar. The 1973 constitution had explicitly established the Ba’ath (Renaissance) Party as the "leading party in the society and the state." In the 250-seat unicameral parliament, the Ba'ath Party led the National Progressive Front. This included other leftist and nationalist parties allowed to exist as loyal adjuncts.

There was no multiparty system in Syria during the 57-year rule of Hafez al-Assad and his son Bashar. The 1973 constitution had explicitly established the Ba’ath (Renaissance) Party as the "leading party in the society and the state."

Under the 1973 constitution, power was concentrated in the president, who appointed and dismissed the prime minister and cabinet at will. Until 2012, the Ba'ath Party leadership nominated a candidate for president for approval by the parliament. The choice was then confirmed in a referendum lacking any other candidates. Changes to the constitution in 2012 introduced direct elections and a two-term limit. Despite already having served two terms, Bashar al-Assad ran again in 2014 and 2021 under the amended constitution. He received 92 and 95 percent of the vote, respectively, against token opposition.

Advancement through the ranks of the party, government and military depended on loyalty and personal connections. Hafez al-Assad favored members of his Alawite sect, a Shi’a denomination making up 11-12 percent of the population, a practice continued under his son, Bashar, although he broadened his patronage to include several Sunni groups.

Criticism of the government or suspected disloyalty brought quick reprisals, including arrest, torture and murder. Control was maintained through an elaborate internal security network incorporating police, intelligence services, the military and a network of civilian agents. Repression intensified during a protracted civil war that began following the military suppression of Arab Spring protests in 2011 (see sections below).

After 13 years of armed civil conflict, an Islamist rebel army carried out a surprising offensive in late December 2024 that toppled the Baathist regime of Bashar al Assad. The Syrian people celebrated the fall of the regime, but at this writing it remained unclear what system of government would replace it in the war-torn country. The sections below and Current Events describe the 25-year period of Bashar al-Assad’s rule.

A Brief “Damascus Spring”

[The “Damascus Spring” in 2000] was quickly put to an end. Assad ordered the arrests of many he had encouraged to speak up for reform.

At first, the succession of Bashar al-Assad to power in 2000 brought hope of change. In his first six months in office, he ordered the release of 600 political prisoners, allowed public debate, and took initial steps at reform. Some referred to this period as “the Damascus Spring” in reference to the 1968 communist reform movement in Czechoslovakia called the Prague Spring. Like the Prague Spring, which was suppressed by the Soviet Union, the Syrian version was quickly put to an end. Assad ordered the arrests of many he had encouraged to speak up for reform.

Some civic and human rights activists continued to challenge the regime internally, but many were imprisoned or forced to emigrate. Thereafter, Assad reinforced the state’s repressive apparatus and maintained control over society through police, security and other government agencies.

Assad Cracks Down Again

Following popular pro-democracy uprisings in Tunisia, Egypt and other Middle Eastern countries in late 2010 and early 2011 ─ collectively called the “Arab Spring” ─ Assad again hinted at making changes to the constitution. When no action was taken, masses of people took to the streets in March 2011 in pro-democracy protests in Damascus and the city of Deraa. They demanded the release of political prisoners and a new constitution. Assad ordered tanks and soldiers to put down the protests in Deraa and authorized police to fire on protesters in Damascus. Subsequent protests in Damascus and other cities were mostly met with force, although some were so massive the authorities let them take place without attack.

Masses of people took to the streets starting in March 2011 in pro-democracy protests. A demonstration in Hama in July as Syrian forces besieged the city. Creative Commons License. Photo by Syrian Revolution Network.

The Civil War Begins

In June 2011, Assad announced “all-out war” on the opposition. The government launched military actions in the northwest city of Jisr al-Sigur, followed by attacks on other cities where a new Free Syrian Army, made up of government deserters and volunteers, had emerged. As police and security forces cracked down on all internal dissent, the military stepped up attacks on major cities where rebels took up arms, such as Homs. Military forces killed indiscriminately, without regard to civilians or historical sites.

In the beginning, the Free Syrian Army (FSA) showed surprising strength. It withstood heavy assaults by government troops, tanks, artillery and planes to keep hold of key cities and areas. FSA leaders joined with other groups in exile to form an opposition alliance called the National Coalition of Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces (SOC). Headquartered in Turkey, the SOC was recognized by some foreign governments.

By mid-2014, despite rebel forces still holding key areas in various regions, the Syrian government had reestablished military control over much of the country.

The SOC demanded an end to the Assad regime and establishment of a democratic government. The SOC, however, had unstable leadership and split over strategy, especially on whether to participate in international talks that included the regime. The SOC also had difficulty maintaining its authority over rebel-held territories, especially those held by extremist and fundamentalist groups backed by Saudi Arabia and other Arab states.

By mid-2014, despite rebel forces still holding key areas in various regions, the Syrian government had reestablished military control over much of the country.

The Civil War Expands

Extremist groups tied to the al Qaeda terrorist network formally broke from the National Coalition of Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces in 2014 to form a rebel alliance committed to establishing a caliphate in Greater Syria. These groups often battled with the more secular Free Syria Army rather than the government.

Starting in June 2014, the largest and most extreme group, the Islamic State of Syria and Iraq (ISIS), first expanded its hold in eastern Syria. It then occupied large territories in Iraq. Having separated from al Qaeda, ISIS declared itself ruler of a new Sunni caliphate called the Islamic State and carried out many atrocities against Iraqis and Syrians. ISIS targeted Shi’a, Yazidi and Kurdish minorities as well as Sunnis violating its fundamentalist laws.

After Russia’s intervention starting in 2015, many cities were targeted for air assaults, including the ancient city of Aleppo. Much of the city lies in ruins today.

In response, the United States organized a coalition of NATO and Middle Eastern countries in 2015-16 to carry out sustained air strikes against the Islamic State and increased its assistance to Iraq’s military, the Free Syria Army and the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). By 2019, after intense fighting, the Islamic State had lost all of its territory and the SDF had gained control over much of Syria’s northeast.

Russian Intervention

Starting in 2011, the United States and other countries imposed economic and trade sanctions on the Assad regime and the Arab League expelled Syria. But no international initiative to stop the war was successful. Syria’s allies, Russia and China, vetoed coordinated sanctions or military action by the United Nations. Meanwhile Russia, Iran and others provided arms and other support to the Assad regime.

In late 2015 . . . the Russian Federation established air, ground and naval bases at the Syrian government’s request and began coordinated military and air strikes with Syrian forces against rebel-held territory.

In late 2015, as the position of Syria’s armed forces weakened due to ISIS’s advances, the Russian Federation established air, ground and naval bases at the Syrian government’s request and began coordinated military and air strikes with Syrian forces against rebel-held territory. Russian President Vladimir Putin claimed that the military operations were directed at the Islamic State, but they focused on areas held by the Free Syria Army. Russian ground forces were later withdrawn but air strikes, often aimed at civilians and civilian infrastructure, continued to support Syrian government forces, which retook several key cities and other rebel-held territory as a result.

The Humanitarian and Refugee Crisis

The civil war in Syria, and especially the unchecked brutality of the Syrian government against its own people, has resulted in one of the worst humanitarian catastrophes since the end of World War II.

In 2011, the UN Human Rights Council established the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic (IICI). Until today, it has chronicled the government’s abuses of human rights. In its 7th report, issued in February 2014, the Commission totaled its findings over the first three years of the civil war. More than 6.5 million people were internally displaced; more than 2.6 million people, half of them children, had fled to neighboring countries; nearly 150,000 people had been killed. The numbers only continued to rise (see Current Issues).

In 2015, up to one million Syrians joined others fleeing conflict in Iraq, Afghanistan and north Africa to try to gain refuge in Europe. This mass exodus brought about the worst refugee crisis since World War II. Some European countries closed their borders. Even countries welcoming the refugees, like Germany, were overwhelmed by the magnitude and took action to halt the refugee flow from refugee camps in Turkey (see Country Study).

In February 2016, the IICI’s 10th report detailed the systematic arrest and torture of tens of thousands of Syrians. Many, the report said, had died in imprisonment or were left to die from wounds inflicted by torture.

In addition to the humanitarian catastrophe, many of Syria’s ancient historical sites, which were preserved over millennia, have been ruined in indiscriminate warfare by the Syrian government or were deliberately destroyed by the Islamic State.

Current Issues

Despite the Arab Spring uprising and the ongoing civil war, President Bashar al-Assad refused demands for him to resign and defied all international initiatives to bring an end to the conflict. There was no reform towards a multiparty system. The Ba’ath Party retained full control of the National Progressive Front, which included a number of small leftist and nationalist parties allowed to exist only as loyal adjuncts to the regime. While the 2012 constitution formally established more possibilities for non-Ba’ath parties to register, there was no change in practice. Electoral Commissions (controlled by the president) had to approve any independent parties or individual candidates.

Bashar al-Assad has been president since 2000. In 2012, the constitution changed to establish a two-term limit, but only going forward. His current term ends in 2028. A poster from the 2014 election campaign. Creative Commons License. Photo by Hosein Zohrevand.

Parliamentary elections took place in 2012, 2016 and 2020. The opposition boycotted all elections given there are no real means to compete. The 2020 elections had record low turnout (33 percent) and were conducted in only the territory under government control. The official results awarded seats to 183 members from the National Progressive Front (167 from the Ba’ath party) and 67 so-called independents.

Revisions to the constitution in 2012 established a two-term limit on the presidency. Assad then asserted that this applied to him only going forward. Despite having already served two seven-year terms, he put himself forward in the 2014 and 2021 presidential elections. By official count, he received 92 and 95 percent of the vote, respectively, against token opposition. His latest term ends in 2028. With power fully concentrated in the presidency, Assad, aided by his brother Maher, kept full control of the government and its military and security services.

From 2020-21, there were cease fire agreements across the different fronts in the civil war. But the Syrian government, with Russian support, continued to carry out military operations. The government held control of about 70 percent of territory, with the northeast held by the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces. Parts of the northwest and some other areas were under control of the more secular Free Syrian Army and an Islamist rebel army. As of mid-2024, at least 570,000 people had been killed since 2011, mostly civilians, with ninety percent attributed to Syrian government attacks.

The Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic provided an overview of the conditions in its February 2023 summary to the UN Human Rights Council. It wrote:

The conflict intensified across several front lines, with devastating consequences for civilians. Government forces used cluster munitions on a densely populated displacement camp in Idlib while children were preparing for school, killing at least 7 civilians and injuring at least 60 others. A rocket attack killed 16 civilians and injured 29 others in the city of Bab in the eastern countryside of Aleppo.

Insecurity persisted across government-controlled areas, notably in the south, with unabating clashes and targeted killings. Arbitrary arrests, disappearances and deaths in detention continued. . . .

More than 13 million people are displaced or refugees at a time when 90 per cent of all Syrian civilians live in poverty, and 15.3 million are estimated to require humanitarian assistance to survive.

Nevertheless, parts of the international community moved towards re-establishing ties with the government, a process accelerated by the massive earthquake that hit southern Turkey and northern Syria in February 2023. The Arab League, for example, re-admitted the Syrian Arab Republic on May 19 on the grounds that exclusion had not resulted in ending the civil war.

The massive earthquake in Turkey and northern Syria in February 2023 (shown here) accelerated a process to normalize diplomatic relations with Bashar al-Assad’s regime. Creative Commons License. Work by Adem.

The restoration of normal diplomatic relations placed the fate of refugees in doubt. Jordan (650,000 refugees), Lebanon (1.5 million) and Turkey (3.3 million) all began actions to force refugees to return despite the IICI’s findings. Still, The United States, the EU and other countries continue to maintain a wide array of sanctions on the regime and on individuals responsible for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and human rights abuses.

Despite these conditions, there continued to be manifestations of opposition against the Assad regime. In August 2023, antigovernment protests erupted in the southern provinces of Al-Suwayda and Daraa over economic conditions. They lasted several weeks. More protests were reported throughout 2024.

After 13 years of armed civil conflict, an Islamist rebel army, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), carried out a surprising offensive in late December 2024 that toppled the Baathist regime of Bashar al Assad. The Syrian people celebrated the fall of the regime, but it remains unclear at this writing what system of government will emerge in the war-torn country. The HTS leader, Ahmed al-Sharaa, has been appointed president by an interim ruling council and there is a dialogue with different groups in Syrian society to discuss a new constitution. Given former ties of HTS to the al Qaeda terrorist group, the international community moved slowly to assess the new situation and many countries retained sanctions.

The content on this page was last updated on .