Summary

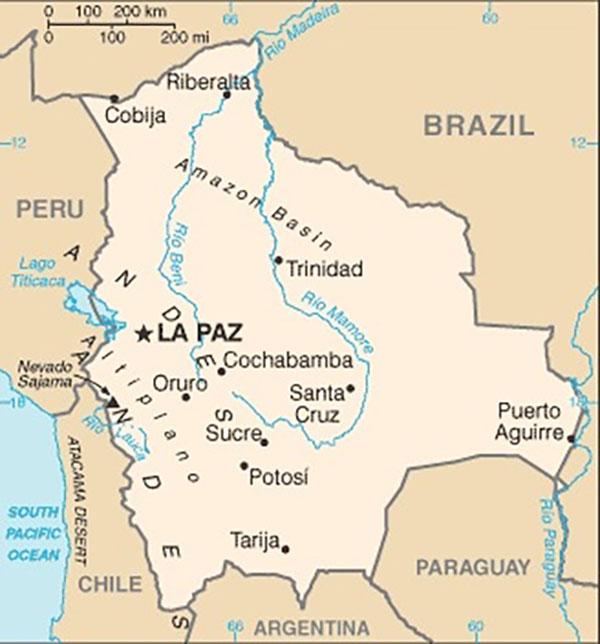

Map of Bolivia

Bolivia (officially the Plurinational State of Bolivia) is a unitary republic with a constitutional democracy and presidential system. Before 1982, Bolivia’s history after independence was largely one of harsh dictatorship or unstable democratic governance. It has had 40 years of civilian rule but faces significant challenges following a political crisis in 2019-20.

In 2003 and 2005, mass street protests led by Evo Morales, an Amerindian leader, caused the fall of successive governments. Morales then won the presidential election by a clear majority, becoming the first indigenous president in the country’s history and the first candidate ever to win by a majority vote. Looking to previous radical governments from the 1930s and 50s, Morales nationalized oil and gas resources, legalized coca (a traditional Amerindian crop), and instituted regional autonomy.

Despite a constitutional two-term limit, the Supreme Court allowed Morales to run and win a third-term in 2014; the Legislative Assembly then removed the term-limit, allowing him to run again in 2019. Disputed results, however, led to violent protests by competing parties, prompting Morales to resign and depart to Mexico. An interim government, supported by the security forces, was established and it re-held presidential elections in late 2020. This time, the election was won decisively by Luis Arce, the candidate of Morales’s party, the Movement Toward Socialism (MAS).

Bolivia is the 28th largest country in the world by area and the fourth largest in South America. Land-locked in central South America, Bolivia is bordered by five countries (Argentina, Chile, Peru, Brazil and Paraguay). The population is small (78th in the world) at approximately 12.2 million (2023 UN estimate). Upwards of 50 percent of the population is ethnically indigenous, or Amerindian, with the largest groups being Quechua and Aymara. The remaining population is white, mestizo (mixed race), Black, and other native groups. Bolivia possesses rich soil and resources, including some of the largest natural gas reserves in the Western Hemisphere. But it has South America's fourth poorest economy in per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP) at $4,014 per annum (ranked 126th in the world). In nominal GDP, the International Monetary Fund projects Bolivia’s 2024 output at $49 billion (ranked 93rd in the world).

History

Pre-Columbian Civilization and Spanish Conquest

The Bolivian highlands have likely been inhabited for at least 12,000 years. The development of farming communities dates to around 3000 BCE. One of the great ancient Andean civilizations, located near Bolivia's Lake Titicaca, flourished for centuries before falling into decline after 1000 CE. The Aymara-speaking people who later lived in the region were conquered by the Quechua-speaking Inca empire in the 15th century.

Spanish colonial rule was based on a system of large estates and other holdings (encomiendas) for exploiting the silver and tin mines. These were largely worked by the indigenous population at minimal pay.

The Spanish colonial conquest of the Inca civilization in the early to mid-1500s allowed Spain to extend its control from Central America to much of western and central Latin America, including the area of Bolivia (then called Upper Peru). Among the main discoveries was an Inca silver mine at Potosi. This area remains rich in silver and other natural resources and has played a dominant role in Bolivia's history.

Spanish colonial rule was based on a system of large estates and other holdings (encomiendas) for exploiting the silver and tin mines. These were largely worked by the indigenous population at minimal pay. As representative of the Spanish monarch, the governor of the territory dispensed the mines' riches to privileged elites of Spanish descent, who presided over Bolivia's economic, social, and political life even after the end of Spanish rule.

From Bolívar to Bolivia

Upper Peru was liberated from Spain in 1825 by the revolutionary forces of Simón Bolívar (who had already freed a swath of Spanish-controlled territory extending north to Venezuela). Bolívar oversaw the writing of the country's constitution and the new republic gained its name in part to convince him not to unite it with Peru. His top lieutenant, Antonio José de Sucre, became the first president, but was forced from power in 1828. A new president, Andrés de Santa Cruz, stabilized the economy and organized the country's internal affairs. His ambitions to create a confederation with Peru, however, led to warfare with the two countries' neighbors. In 1839, Bolivia was defeated by Chilean forces and the confederation project ended.

From Generals to Radicals

After Santa Cruz's ouster, Bolivia experienced 40 years of erratic rule by a series of "caudillos," or strongmen. In 1879, Bolivia lost the mineral-rich Atacama region, the country’s only point of access to the sea, to Chile in the War of the Pacific. At this time, two political parties formed: the Conservative Party, which advocated a quick peace with Chile to include mining concessions, and the Liberal Party, which rejected the peace deal and criticized Bolivia's dependence on foreign mining interests. Under the Liberals, a constitution was adopted in 1880 establishing a bicameral legislature, but the basic law continued to restrict the vote to a small minority based on property and literacy qualifications. Several decades of relative political stability followed, but power often changed hands by force. Disastrous losses in the 1932–35 Chaco War with Paraguay led to a military seizure of power in 1935. A series of nationalist military governments proceeded to take control of Bolivia's natural resources and introduce land reform, but in 1947–52 Conservatives reasserted themselves in government, stemming for a time the nationalist Left.

The 1952 Revolution

In 1952, the Nationalist Revolutionary Movement (MNR), a leftist party first formed in 1941 and led by Víctor Paz Estenssoro and Hernán Siles Zuazo, seized power by force. The MNR had ruled from 1943 to 1946 and won the 1951 elections, but it was prevented from assuming office by the military. In response, the MNR assembled armed civilians and gained support of portions of the security forces to seize control. Backed by peasants and workers, the new revolutionary government nationalized resources, enacted land reform, and abolished property and literacy requirements for voting. While influenced by nationalist and Marxist movements, the MNR government espoused democracy and did not adopt repressive features.

Military Dictatorship Returns, But Democracy Is Restored

Victor Paz Estenssoro, who helped lead the 1952 Revolution and served as president of Bolivia from 1952 to 1956 and 1960 to 1964. He won elections again to serve as president in 1985 to 1989 after a period of military dictatorship.

A military coup overthrew Paz Estenssoro after his 1964 re-election. Bolivians then lived through 18 years of intermittent military dictatorship, during which essential constitutional provisions were suspended. Democratic politics were fully restored in 1982 following a national strike and protest movement. Siles Zuazo, one of the original MNR leaders who had served as president from 1956-60, was again elected to the office. In 1985, Paz Estenssoro succeeded him, facing an economy in grave crisis with a 10–12 percent annual drop in GDP and hyperinflation at 24,000 percent. Contrary to the MNR’s previous radical platform, he carried out a program of stringent budget and monetary policies and privatization of state enterprises. These actions are credited with helping the economy out of dire crisis, but many MNR supporters felt betrayed by them.

Coca Eradication and Historical Exclusion

In 1997, General Hugo Banzer, a conservative former military dictator, won election to end the MNR’s continuous political success since 1982. Banzer’s government inflamed social tensions by working with the United States government to fight cocaine production through the eradication of coca, a traditional Amerindian crop. The eradication campaign by the military brought a number of issues to a head, most notably the exclusion and poverty of the Aymara and Quechua peoples. Until 1952, some 85 percent of the land was held in large estates, while these two indigenous groups, representing 70 percent of the population, worked mostly under a sharecropping system. Land reform at the time provided Aymara and Quechua peasants with small plots, but enough mostly for subsistence farming. The cultivation of coca, which had traditional uses, was their most important cash crop. Banzer’s eradication program caused a significant decline in indigenous farmers' livelihoods.

The Weakness of the Presidential System

Since the 1952 revolution, no Bolivian presidential candidate had gained 50 percent of the popular vote. According to the constitution, The Legislative Assembly held the power to choose the winner from among the three top candidates. While in theory this might lead to the development of coalition politics (see Multiparty System), in practice this delegation of authority to the Legislative Assembly often meant that the president had no clear mandate. This systemic weakness became evident when Gonzalo Sánchez Lozado was elected in 2002 after receiving just 22 percent of the popular vote. He was forced to resign in October 2003 after a proposed tax increase and a plan to export natural gas through Chile sparked mass protests. These were organized by a new radical party, the Movement Toward Socialism (MAS), led by Evo Morales, a Quechua leader. Lozada's constitutional successor, Vice President Carlos Mesa, was unable to muster political support for his own administration. He resigned in June 2005 amid further demonstrations led by Morales demanding state control over energy and mineral resources.

The December 2005 "Revolution"

In the December 2005 presidential elections, Morales won a landmark victory by securing 55 percent of the vote. It was the first time in decades that the presidential election was decided by an outright majority and thus not decided by the Legislative Assembly.

In leading massive street campaigns, Evo Morales harkened back to the original MNR government and the platform of the 1952 revolution. He wove together the themes of defending coca crop cultivation against U.S. pressure, addressing the historical exclusion of the indigenous population, and asserting national and popular sovereignty over natural resources. The last issue, recurrent for much of Bolivia's history, was reignited by a boom in silver and tin mining and new discoveries of hydrocarbon reserves (making Bolivia the continent's second-largest depository of natural gas).

In the December 2005 presidential elections, Morales won a landmark victory by securing 55 percent of the vote. It was the first time in decades that the presidential election was decided by an outright majority and thus not decided by the Legislative Assembly. Morales was inaugurated as the first indigenous president in Bolivian history.

Consent of the Governed

While the country achieved national independence and established a new constitution in 1825, Bolivia’s War of Independence was fought mostly for the few. For 125 years afterwards, Bolivian politics, due to its presidential system, reflected much of the continent in its swings between constitutional and dictatorial rule.

While the country achieved national independence and established a new constitution in 1825, Bolivia’s War of Independence was fought mostly for the few. For 125 years afterwards, Bolivian politics, due to its presidential system, reflected much of the continent in its swings between constitutional and dictatorial rule. During this time, the indigenous Aymara and Quechua Amerindians as well as much of the Black and mestizo population of indigenous heritage were largely dispossessed. Bolivia's politics and economy were governed mainly by a small population of wealthy Bolivians of Spanish heritage.

It is only in Bolivia's modern history, beginning with the 1952 revolution, that consent of the governed can be considered more fully. Universal suffrage was enacted and a popular government serving the broader interests of peasants and workers was elected.

It is only in Bolivia's modern history, beginning with the 1952 revolution, that consent of the governed can be considered more fully. Universal suffrage was enacted and a popular government serving the broader interests of peasants and workers was elected.

In 1964, a coup ended the MNR government, introducing unstable military rule that lasted until 1982, when a national strike helped bring a resumption of civilian rule and democratic politics. Elections returned MNR leaders to power, but at a time of economic crisis forcing adoption of austerity policies that went against MNR’s previous platform. A former military dictator regained office through elections in 1997 that re-introduced heavy-handed rule, especially over the Indigenous population.

Evo Morales’s election in 2005 established a more representative majority government. It was led for the first time by an Amerindian. Morales set out to fulfill his popular agenda to nationalize energy resources and utilities, renegotiate extraction contracts with foreign firms, adopt land reform and progressive taxation, protect coca production, and broaden government programs.

Campaign posters for a 2008 plebiscite on Evo Morales’s presidency that broke an impasse on writing the new constitution. The new constitution was adopted in 2009.

The New Constitution and Its Challenges

In a three-year process marked by political disputes with traditional parties, the Constituent Assembly put forward a new constitution in 2009. In a plebiscite, the constitution passed with 61 percent of a high-turnout vote.

The new constitution changed the country’s name to the Plurinational State of Bolivia (Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia) and amended its presidential system by establishing a run-off election if no candidate achieved a majority vote (thus removing the Legislative Assembly’s determination of the presidency). It also set a two-term limit on the presidency. The constitution also included broad media and other freedoms. Reflecting the country’s new name, the constitution instituted a dual legal system for indigenous peoples allowing limited regional autonomy and enshrined political representation for Amerindians by reserving a minimum number of seats in elected bodies.

Morales was re-elected in 2009 under the new constitution with 65 percent of the vote in a record 95 percent voter turnout. By 2010, all nine territorial departments had passed regional autonomy statutes and MAS won six of the governorships in regional elections. In 2011, opposition candidates won mayoralties in most of the major cities establishing pluralist governance. Bolivia’s new constitution thus helped establish a more broad-based consent of Bolivia’s citizens allowing for regular political competition.

Morales’s governance, however, was marked by infringements on the rule of law and other freedoms. Political scholars called Morales’s style as a “politics of conflict” with constituencies and regional leaders who opposed him. His government’s practices included irregular prosecutions of rival politicians and confrontations with civic leaders and trade unions.

Morales successfully challenged his constitution’s two-term limit, a provision that opposition parties had insisted upon in the Constituent Assembly. In 2014, the Constitutional Court, dominated by MAS appointees, ruled that Morales’s first term, starting in 2006, did not count towards the limit since the election was prior to the new constitution. Morales won the 2014 election with over 60 percent of the vote. Soon thereafter, however, he started seeking the possibility for a fourth term, including by changing the constitution by referendum in 2016. Surprisingly, he lost the referendum by a narrow 51-49 percent margin. It led to a new crisis in Bolivia’s political history.

Current Issues

When Evo Morales lost the 2016 referendum, he refused to abide by the outcome and instead had the MAS dominated legislature remove the term limit provision from the constitution. The Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE), also dominated by MAS appointees (see below), allowed Morales’s candidacy for the 2019 elections.

Initial results in the October 2019 elections indicated Morales had failed to meet the necessary 50 percent threshold to avoid a run-off with Carlos Lozada, a previous president running in an anti-left coalition. The TSE, however, then reported a slight 50 percent victory for Morales in final results. This determination was questioned by the election monitoring body of the Organization of American States (although later an independent study largely confirmed the TSE’s results).

Protests by both opponents and supporters of Morales lasted three weeks with ongoing violence, mostly initiated by security forces. As it became clear the army and security forces had abandoned support for his continued governance, Morales resigned and went into temporary exile in Mexico. Other top officials resigned in protest of the use of force by security forces to quell protests.

A protest in Santa Cruz in 2019. Violent conflicts over the outcome of the presidential election led to the resignation and self-exile of Evo Morales and a crisis for Bolivian democracy. Photo by Ariela2020. Creative Commons License

A relatively unknown conservative senator, Jeanine Añez, asserted her position as next-in-line to assume the presidency, which the Constitutional Court affirmed. Claiming to form an interim government until new elections could be held, Añez asserted arbitrary powers to have protestors who had supported Morales and the MAS movement punished for sedition and terrorism. In doing so, she cleared security forces of accountability for using unnecessary force. Her actions led to fears Añez planned to establish an authoritarian government.

Under both domestic and international pressure, Añez fulfilled a promise to hold another national election in October 2020 and withdrew her own candidacy for the presidency. In the presidential contest, Luis Arce, the economy minister and Morales’s hand-picked successor, won by a decisive margin, receiving 55 percent against former president Carlos Mesa, who garnered just 28 percent support. Since the election, Arce has sought to distance himself publicly from Morales (who returned from exile soon after the elections), but has remained loyal to the overall MAS program.

In the legislative elections held at the same time, MAS won 75 of 130 seats in the Chamber of Deputies and 21 of 36 seats in the Senate. Two opposition parties (Citizen Community and We Believe) secured 55 seats and 15 seats respectively in the Chamber and Senate. As in most elections, turnout was high (84 percent of eligible voters). Regional and municipal elections held in the spring of 2021 were also competitive, with MAS winning many regional races and the opposition winning in large municipal races.

Human rights organizations have long criticized Bolivia’s lack of an independent judiciary and generally its system of rule of law.

Human rights organizations have long criticized Bolivia’s lack of an independent judiciary and generally its system of rule of law. In 2011, under the new constitution, Bolivia became the only country in the Western hemisphere to institute elections for national and regional court officers. While justices are elected by the citizenry, it is only from among candidates proposed by the bicameral Plurinational Legislative Assembly, which has been dominated by one party, MAS. As well, most other judicial positions (80 percent) have no fixed terms, leaving judges subject to political pressure to make decisions or risk losing their jobs.

According to human rights organizations, Presidents Morales, Añez and Arce have each used the judicial system as a political weapon. As noted above, Añez ordered terrorism and sedition charges to be levied against approximately 250 MAS supporters from the 2019 protests while clearing security forces of accountability for using unnecessary force. After his election, Arce ordered a blanket amnesty for the protesters, some of whom are believed to be credibly accused of serious crimes, and ordered charges against security officers.

Following a 2021 report of the Interdisciplinary Group of Experts (GIEI), Arce reversed these decisions and promised efforts to de-politicize the judiciary. The GIEI had been established in agreement with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights of the OAS to examine the events in 2019. Its lengthy report documented violence on both sides but noted the larger scale violence of the security forces.

Arce’s decision, however, did not extend to the prosecution of Jeanine Añez, who was arrested in April 2021 and held for 15 months until trial. A lower court found her guilty of breaching her duty in seizing the presidency in 2019 and in enacting executive decisions contrary to Bolivia’s Constitution, most significantly in ordering repression against protesters and granting immunity to security services. International human rights organizations criticized Añez’s conviction and her sentencing to 10 years’ imprisonment as re-affirming the use of the judiciary against political opponents. Government supporters defended the conviction on the grounds that Añez was being held responsible for seizing and exercising power illegitimately. Human rights organizations, however, point to other political prosecutions. Luis Fernando Camacho, a prominent opposition leader and governor of the Santa Cruz region, Bolivia’s richest, was arrested in December 2022. He remained held under pre-emptive detention on charges of terrorism at the end of 2023.

On June 26, 2024, another coup was attempted by a top general, Juan José Zuñiga, and some allies in the military. He and a group of soldiers stormed the presidential palace but retreated three hours later as the coup gained no further support and the plotters were confronted by security officers and a mass of people supporting President Arce. It was suspected that the coup was attempted to take advantage of political conflict between Arce and Evo Morales over control of the MAS party. The state’s security services and other military leadership, however, demonstrated continued adherence to civilian rule.

Civil society is vibrant and freedom of association is respected. Regional organizations, citizens’ groups, trade unions, and leaders of indigenous groups have strongly pressed all governments to uphold their rights and interests.

Arce and Morales are competing for who will be selected as candidate for the elections scheduled for 2025. The Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE) had annulled the decision of the MAS National Congress in October 2023 to nominate Evo Morales as its presidential candidate for 2025. (The Congress had nominated Morales despite the two-term constitutional term limit, which remains in place.)

Overall, civil society is vibrant and freedom of association is respected. Regional organizations, citizens’ groups, trade unions, and leaders of indigenous groups have strongly pressed all governments to uphold their rights and interests. Freedom of the media and expression is guaranteed and generally respected but journalists face intimidation and violence. The National Press Association has documented numerous such cases of intimidation against journalists and outlets for coverage critical of, in sequence, Morales, Añez and Arce.

Freedom House has ranked Bolivia alternately as “free” and “partly free” since the end of military dictatorship in 1982. It has had “partly free” measurements since the 2005 elections and 2009 plebiscite, although at times close to the “free” threshold. While the country has had high measurements for free and fair elections, it has lower ones for fair electoral processes, free assembly and expression, and rule of law. In recent reports, Freedom House expressed growing concern for increasing levels of societal and police-led violence due to the 2019 elections; lack of judicial independence; conditions of incarceration; and threats to media freedom.

The content on this page was last updated on .