Summary

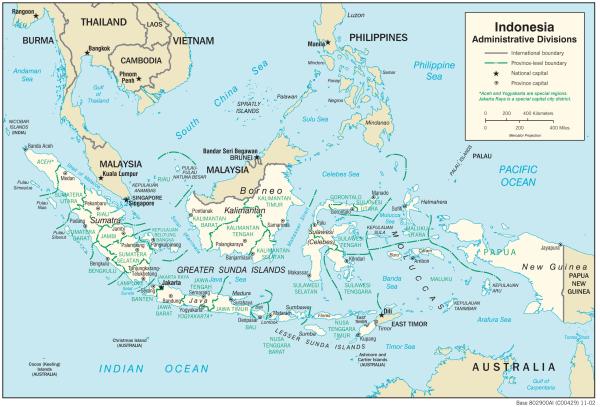

Map of Indonesia

Indonesia, an archipelago nation made up of more than 17,500 islands (6,000 of which are populated), is a unitary republic with a mixed presidential-parliamentary system.

Indonesia’s modern human habitation dates to around 4,000 BCE. From the early centuries BCE, the principal Indonesian islands had Hindu, Buddhist and, later, Islamic sea-faring kingdoms that vied for dominance. From the 16th to 20th centuries CE, Indonesia was under Dutch colonial rule. During World War II, the Japanese army ruled with local Indonesian administration. After the Japanese withdrawal in 1945, Indonesian leaders declared independence. A nationalist army fought Dutch forces that attempted recolonization. Netherlands recognized Indonesia’s independence in 1949.

Independent Indonesia was led first by President Sukarno, who over time adopted what was called “Guided Democracy.” In 1963, he declared himself “president for life.” In 1965, the head of the armed forces carried out a coup to defeat a communist insurgency, using brutal means. General Suharto formally replaced Sukarno as president in 1967 and ruled for 31 more years until being forced to resign in 1998 due to public protests. Since 1998, Indonesia has held free, fair and regular elections, experienced peaceful transfers of power and improved respect for human rights. But corruption, abuses by security forces and an increase in violations of civil liberties have set back political progress.

One region, East Timor, achieved independence in 2002 following a referendum held under United Nations auspices. (East Timor had gained independence from Portugal in 1974 but came under Indonesia’s rule when Suharto seized control in a military invasion in 1975.) Despite resolving another regional insurgency in Aceh, Indonesia has faced significant violence from terrorist and separatist movements over the last decades.

Indonesia, which lies between the Asian and Australian continents and the Indian and Pacific Oceans, has the world’s 4th largest population (278 million inhabitants as of 2023). Eighty-seven percent are recognized as adherents to Islam, making Indonesia the world’s largest Muslim-dominant country. Christians make up 10.7 percent and Hindus 1.7 percent. The Economist rates Indonesia among the fastest growing economies globally over the previous two decades and in 2023 it had the world’s 16th largest economy. The International Monetary Fund projects Indonesia’s 2024 nominal Gross Domestic Product (GDP) at $1.5 trillion, but its GDP per capita is $5,271 per year, ranked 114th in the world.

History

Early History and Kingdoms

Fossil records show human ancestors inhabited the Indonesian archipelago as far back as 700,000 years ago. Modern human habitation dates to at least 4000 BCE. With the rise of seafaring city-states in the first millennium BCE, there emerged Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms on principal islands. Buddhism was introduced to kingdoms in western Java, western Borneo, and the southern Malay Peninsula. The Hindu-dominant Srivijaya Kingdom ruled on the large island of Sumatra from the 6th to the 15th centuries CE.

With the rise of seafaring city-states in the first millennium BCE, there emerged Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms on principal islands.

As in Malaysia (see Country Study), Arab traders arriving in the 11th century introduced Islam to the islands. The last prince of the Srivijaya Kingdom adopted Islam in 1414 CE and began a new kingdom on the Malay Peninsula called the Sultanate of Malacca. Several other kingdoms developed on Java, the main Indonesian island. The Majapahit kingdom ruled there from 1293 to 1500 but was driven to the outpost of Bali by the Sultanate of Malacca.

Colonization: Levels of Brutality

Portugal established the first European foothold, but the Netherlands gained dominance on the islands starting in 1602 (see Country Study). In an empire-building practice similar to Great Britain, the Dutch parliament granted the Dutch East India Company (VOC) a monopoly over Indonesian trade. The VOC quickly seized key ports on major islands to establish control over the lucrative spice trade. The islands became known as the Dutch East Indies.

Dutch rule was marked by brutality. In 1619, the Dutch took the Java port city of Jayakarta and razed much of it to the ground.

Dutch rule was marked by brutality. In 1619, the Dutch took the Java port city of Jayakarta and razed much of it to the ground. Renamed Batavia, it was made the capital of the Dutch East Indies and rebuilt as present-day Jakarta on the model of Amsterdam. Another example of Dutch early rule was the order to kill much of the Banda Islands population to secure a monopoly trade for nutmeg. The islands were repopulated by indentured servants and slaves.

The Dutch East India Company went bankrupt in 1799 after the Netherlands was conquered by Napoleon. The British then secured Dutch East Indies ports. Following Napoleon’s final defeat, the reconstituted United Kingdom of the Netherlands regained control of the archipelago from the British in 1816. The Dutch moved the islands to a system of plantation farming that relied on forced labor. Rubber, spices and coffee were the main crops.

During the 19th century, Dutch rulers denied indigenous Indonesians any voice in administration. A so-called Ethical Policy adopted in 1901 led to investment in local education but not to political representation. Two activists, Sukarno and Muhammad Hatta, emerged as leaders of respective secular and Islamist nationalist groups demanding independence. They were imprisoned by Dutch authorities for ten years in the 1930s. The Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI), aligned with the Soviet Union, also arose as a political force.

When the Dutch captured Jayakarta (today named Jakarta), the governor Jan Pieterszoon Coen razed it to the ground. It was renamed Batavia and rebuilt using engineering similar to Amsterdam for its canals and ports. Above, an engraving of a canal along which Dutch nobility lived. Public Domain. Koninklijke Biblioteek.

Japanese Invasion & the War for Indonesian Independence

During World War II, the Japanese Empire, as part of the Axis Powers, invaded Indonesian islands. To forestall local resistance, the Japanese released Sukarno and Hatta from prison to take over local administration. From these posts, the two built support around a unified theme of nationalism. Japanese occupation was severe — an estimated four million people died from forced labor and starvation. Yet, after Japan's surrender to Allied forces, the wartime administration was not considered a contradiction in the struggle for Indonesian independence.

Queen Julianna ceded sovereignty and recognized Indonesia's independence on December 27, 1949. The cost had been high: 6,000 Dutch soldiers and 150,000 Indonesians were killed in the fighting.

On August 17, 1945, Sukarno and Hatta declared Indonesia's independence. Under a provisional constitution, the president and vice president had executive authority to rule by decree. Using Japanese-trained soldiers, Sukarno and Hatta built an armed nationalist movement to fight first a British force ordered by its government to occupy the islands and then Dutch forces attempting to recolonize Indonesia by seizing key ports and territory.

The resilience of the nationalist movement, as well as international pressure and the Dutch public’s opposition to the cost of continued empire, led to peace talks in the Netherlands. Queen Julianna ceded sovereignty and recognized Indonesia's independence on December 27, 1949. The cost had been high: 6,000 Dutch soldiers and 150,000 Indonesians were killed in the fighting.

Sukarno: "President for Life"

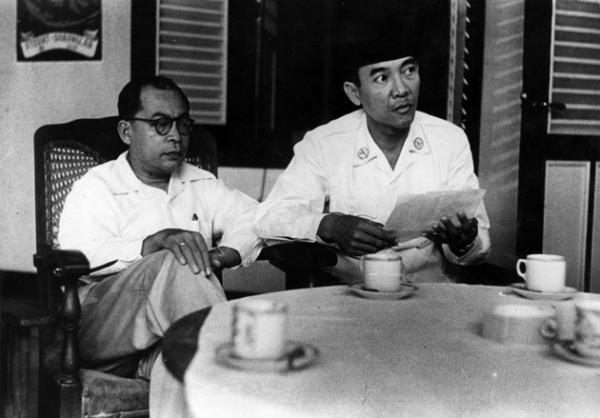

Sukarno (left) and Mohammad Hatta, leaders of the secular and Islamic nationalist movements, are shown here during the rebellion against Dutch recolonization after World War II. Sukarno and Hatta were the first president and vice president of independent Indonesia. Public Domain.

Sukarno continued as president and Hatta as vice president of Indonesia without elections. After several lagging islands joined the new republic, a new constitution was adopted in 1950 that established a unitary republic and parliamentary democracy. The president and vice president would be chosen by parliament.

National elections, however, did not take place until 1955. The political situation was fractious. In the elections, approximately 60 parties won representation to the two-chamber parliament. Although a stable coalition could not be formed, Sukarno was elected president by large margin in the People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR), the congress of both legislative houses. Hatta resigned due to the vice presidency’s new lesser role and became a critic of Sukarno’s governance.

Facing rebellions and military takeovers on several islands, Sukarno then abandoned the 1950 constitution in 1959 . . . He proclaimed a period of “Guided Democracy” and re-established Pancasila, which formed an official part of the provisional constitution, as Indonesia’s state ideology.

Facing rebellions and military takeovers on several islands, Sukarno then abandoned the 1950 constitution in 1959. He re-validated the 1945 version giving him executive power. He proclaimed a period of “Guided Democracy” and re-established Pancasila, which formed an official part of the provisional constitution, as Indonesia’s state ideology. Pancasila establishes five governing principles: belief in “the one and only god”; the unity of Indonesia; a just and civilized world community; democracy based on consensus; and social justice achieved through a command economy.

Sukarno ruled in coalition among the country’s three key political forces: himself, leading the main secular nationalist party, the armed forces and the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI). In 1963, Sukarno asserted himself as first among equals, declaring himself “president for life.”

Suharto and the “New Order” Era

Sukarno, however, was worried about the growing dominance of the military. He had himself strengthened the armed forces with an aggressive foreign policy to retake Papua, the western half of the island of New Guinea, which had remained under Dutch control. Fearing the armed forces’ growing power, Sukarno encouraged the PKI to arm peasants and other groups as a counterforce against a potential military takeover.

Military leaders in turn were concerned about Sukarno’s alliance with the PKI, as well as his growing ties to the Soviet Union and the threat of an armed communist movement. In 1965, six army generals visiting Sukarno were killed by pro-PKI palace guards wanting to forestall an army agreement with Sukarno to weaken the PKI’s influence. The head of the Army Strategic Command, General Suharto, took charge of state power to suppress what was considered an attempted PKI coup. Sukarno remained as president but without real power.

Suharto’s counter-insurgency campaign was among the worst episodes of government-sponsored bloodshed in the postwar period. From 500,000 to 1 million armed and unarmed PKI members, as well as those simply suspected of being communists, were killed.

Suharto’s counter-insurgency campaign was among the worst episodes of government-sponsored bloodshed in the postwar period. From 500,000 to 1 million armed and unarmed PKI members, as well as those simply suspected of being communists, were killed. A similar number were imprisoned.

In 1967, at the end of Sukarno’s term, Suharto had himself elected as president by a newly formed Provisional People's Consultative Assembly. (Sukarno was then placed under house arrest until his death in 1970.) General Suharto retained the 1945 constitution and the state ideology of Pancasila but ruled by harsher authoritarian means.

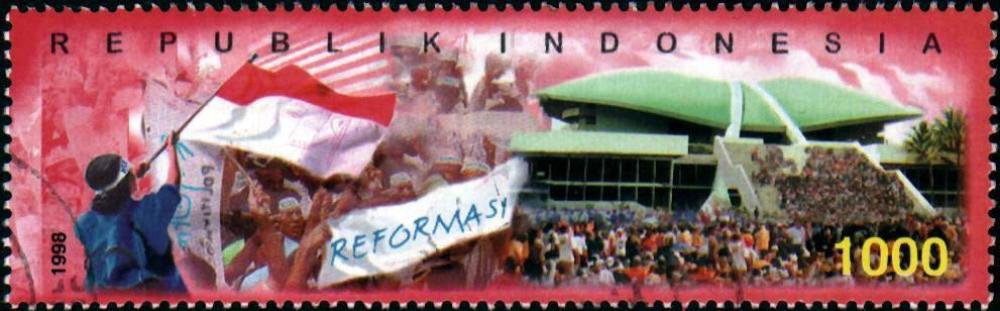

In 1998, the Reformasi protest movement led by Megawati Sukarnoputri (Sukarno’s daughter) brought about the resignation of General Suharto, who ruled for 33 years after carrying out a military coup in 1965 and replacing Sukarno as president two years later. A commemorative stamp of the Reformasi Movement. Public Domain.

The legislature was dominated by what Suharto called his New Order movement. New Order comprised a pro-government political party called Golkar together with three satellite parties loyal to the regime. The People’s Consultative Assembly, with both houses elected under controlled conditions, selected Suharto to seven consecutive five-year terms as president. During Suharto’s 31-year rule, security forces responded to insurrections, terrorism and political opposition with armed force and repression. The government exercised firm control over media, the judiciary and social organizations.

A Hard Victory

During this period, opposition parties existed but faced significant hurdles since only New Order parties could run candidates for office. Yet, throughout Suharto's reign, many individuals braved imprisonment and death to stand up for political, human and worker rights.

[T]hroughout Suharto's reign, many individuals braved imprisonment and death to stand up for political, human and worker rights.

A split in one of the New Order parties, the Indonesian Democratic Party (PDI), would lead to the end of the Suharto regime. PDI had been the party of Sukarno, still a popular figure with the Indonesian public. Suharto had put the PDI within the New Order movement to to give himself greater legitimacy. As part of this veneer, he worked to convince Sukarno's daughter, Megawati Sukarnoputri, having no political experience, to join the PDI. She was elected to the House of Representatives (DPR), the main legislative chamber, in 1987.

Megawati, however, joined PDI not to support Suharto but to reclaim her father’s legacy. In the early 1990s, she won support of party activists to supplant a loyal ally of Suharto as leader the PDI. She was elected at a national assembly hidden from police. The government responded by seizing PDI offices, again installing Suharto loyalists to head the party and banning Megawati’s faction from the 1997 elections.

Megawati Sukarnoputri, elected vice president after the democratic elections in 1999, assumed the presidency in 2001 when her predecessor was recalled for corruption and abuse of power. Megawati achieved significant democratic reforms but did not win re-election in 2004. Presidential portrait, 2001. Public Domain.

Suharto’s public support, however, was diminishing. A financial crisis in 1998 led to adoption of an unpopular austerity plan that the International Monetary Fund required for a bailout fund. When Suharto forced a legislative vote to allow him a seventh term in office, mass protests erupted that showed the enormous dissatisfaction with his long rule. When police shot four students, protests turned violent. Security forces killed 1200 people in suppressing the riots.

Megawati renamed her faction the Indonesian Democratic Party–Struggle (PDI–P). She joined forces with two outlawed Islamist parties — the National Awakening Party (PKB) and the National Mandate Party (PAN) — to demand Suharto's ouster. In the face of domestic and international pressure, Suharto resigned in favor of his vice president, who acted to lift the ban on opposition parties and schedule new parliamentary elections.

A New Start for Democracy

Elections were held in 1999, but under a system still favoring the New Order Movement. Megawati’s PDI-P won a plurality of seats to the House of Representatives while Golkar had the second largest bloc due to seats reserved for the military. The leader of one Islamist party, PAN, opposed women in public office and teamed with Golkar to prevent Megawati from becoming president. They joined to elect Abdurrahman Wahid, the leader of the more moderate Islamist party. But Megawati assumed the vice presidency as the second-place finisher and she ended up succeeding Wahid in 2001 when he was impeached for abuse of power and corruption.

In three years, Megawati achieved significant democratic reforms. These included constitutional amendments to eliminate appointed seats for the military in the legislature, establishing direct national elections for president and vice president, and adopting a federal system to decentralize political power.

In three years, Megawati achieved significant democratic reforms. These included constitutional amendments to eliminate appointed seats for the military in the legislature, establishing direct national elections for president and vice president, and adopting a federal system to decentralize political power. The last reform allowed Megawati to negotiate an end to the 30-year-long rebellion of the Free Aceh movement in 2004 by granting the Aceh province greater autonomy. (East Timor had earlier achieved self-determination in 1999 under UN authority and full independence in 2002 following a referendum.)

Despite these achievements, Megawati lost the country's first direct election for president in 2004 to a former general, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono. Parliamentary elections resulted in the restoration of Golkar as the main party. Yudhoyono’s newly formed Democratic Party came in second. Surprisingly, Megawati’s PDI-P was a distant third.

On the basis of strong economic growth, President Yudhoyono won re-election in 2009 and his Democratic Party supplanted Golkar as the largest party in the legislature. The PDI-P was again third in opposition. In the 2014 elections, however, PDI-P, still led by Megawati, again won a decisive plurality. PDI-P’s win was aided by the party’s winning candidate for president, Joko Widodo, a highly popular governor of Jakarta. Widodo won re-election in 2019, again defeating a former Suharto general named Prabowo Subianto. The PDI-P maintained its plurality in the House of Representatives.

A more detailed description of the period since 1998 and Indonesia’s improvement in human rights is in the following section.

Human Rights

For much of Indonesia's history, its many different indigenous communities lived under either monarchical or Dutch colonial rule and were denied political representation. Colonial rule put most communities under harsh subjugation. The Japanese occupation during World War II relied on local administration by Indonesia’s nationalist leaders, Sukarno and Mohammed Hatta, but its rule was still harsh, resulting in mass death due to forced labor and famine.

Independence was proclaimed by Sukarno and Hatta in August 1945 under a provisional constitution after the Japanese surrender to Allied forces. The Netherlands failed in its attempt at re-colonization and Queen Juliana formally ceded sovereignty and recognized Indonesia’s independence in December 1949. The country was admitted to the United Nations in September 1950.

A new constitution in 1950 adopted by referendum established a full parliamentary system, but democratic elections were not held until 1955. The fractious result left Sukarno as president and Indonesia’s dominant leader but without a stable governing majority. In 1959, Sukarno abandoned the new constitution and instituted what he called “Guided Democracy.”

General Suharto, the head of the armed forces, seized power in a coup in 1965 to thwart a perceived coup by the Communist Party of Indonesia and spent his initial years in power directing its brutal suppression. Suharto ruled for the next 33 years instituting a harsh authoritarian system. He was forced to resign in 1998 as a result of mass protests, part of an ongoing democratic movement (called “reformasi”) led by Sukarno’s daughter, Megawati Sukarnoputri.

Since then, democratic politics have taken root in Indonesia, the world’s most populous Muslim-dominant country, but Indonesia’s governments have not fully grounded respect for human rights. But, as described below and in Current Issues, Indonesia's governments have not fully grounded respect for human rights.

Free and Fair Elections

Parliamentary elections in 1999 instituted greater democratic rule. The People's Consultative Assembly (MPR), the joint Congress of the two legislative chambers, selected Abdurahim Wahid as president and Megawati Sukarnoputri as vice president, but she replaced Wahid after he was removed for trying to usurp power and dissolve Congress in the wake of corruption allegations.

Parliamentary elections in 1999 instituted greater democratic rule. . . . As president, Megawati Sukarnoputri successfully passed constitutional provisions that eliminated previous anti-democratic features.

As president, Megawati Sukarnoputri successfully passed constitutional provisions that eliminated previous anti-democratic features, such as mandatory appointed seats in parliament for the military. All 560 seats in the House of Representatives and 132 seats in the Senate are now directly elected either by party list or in single district elections. Parliament also instituted direct elections for the offices of president and vice president as well as for regional and local offices.

There is general freedom to organize political parties, however the Communist Party remains banned, continuing a Suharto era prohibition. A new law passed in 2017 favors larger parties, particularly in presidential elections. Only parties with minimum 20 percent representation in parliament or a previous 25 percent vote in the last national election may field a candidate.

Indonesia has held democratic national elections since 1999 that international and domestic observers have judged both free and fair. Turnout is generally high (the highest rate was 83 percent in 2019). Above is an informational poster for the 2009 elections. Public Domain. Photo by Josh Early.

Since 1999, five national elections were held for parliament, for president and vice president, and for regional and local offices. Although violence has marred balloting in some regions and there remain questionable ballot practices in others, national elections held in 2004, 2009, 2014, 2019 and 2024 have been deemed free and fair by international and domestic observers.

Peaceful Transfers of Power

Megawati Sukarnoputri and the Democratic Party of Indonesia-Struggle (PDI-P) did not maintain popular support despite her democratic reforms. She lost the first direct presidential election in 2004 to a former Suharto general, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono. This resulted in the first peaceful transfer of executive authority in Indonesia’s history. The former governing party, Golkar, won a plurality in parliamentary elections in 2004. Yudhoyono’s new Democratic Party came in second and PDI-P a distant third.

Joko Widodo, second from right, won the 2014 and 2019 presidential elections as candidate of the Democratic Party of Indonesia-Struggle, against former general Prabowo Subianto (second from left) of the nationalist Gerindra Party. Shown here in 2014 with their vice-presidential candidates at the “lottery” determining ballot placement. Public Domain.

Yudhoyono presided over a period of fitful reform but rapid economic growth spurred by government subsidies of industry. He won re-election in 2009 and his Democratic Party won a decisive plurality in legislative elections over Golkar. The PDI-P and a new nationalist party, Gerindra (Greater Indonesia Party), came in third and fourth.

In 2014 elections, the PDI-P regained support and won a decisive plurality in parliamentary elections on the strength of its candidate for president, Joko Widodo (known as Jokowi). Born in a slum in Surakarta, he became a furniture maker who rose to become mayor of Surakarta and then the popular governor of Jakarta, known for interacting with citizens directly on regular walks through the city. He defeated the candidate for the nationalist party Gerindra with 53 percent of the vote in a two-person election. As a result, there was a second peaceful transfer of power through elections (see also Current Issues below).

Adopting Universal Standards

In 2005, Indonesia joined most nations in ratifying the UN Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and its Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights. Indonesia also ratified all eight core conventions of the International Labour Organization.

In 2005, Indonesia joined most nations in ratifying the UN Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and its Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights. Indonesia also ratified all eight core conventions of the International Labour Organization, one of few countries in the Asia-Pacific region to do so.

In addition, the government established a new human rights office and adopted a National Plan of Action on Human Rights to ensure that Indonesia was in compliance with the new conventions and to protect minority communities “that are most vulnerable to human rights violation." The plan also seeks to reduce poverty and improve quality of life. In 2017, a National Plan of Action on Business and Human Rights was adopted (see Resources).

Mixed Practices

Human rights are more respected in Indonesia today in contrast to the Suharto era. Then political repression was pervasive, civil liberties were routinely violated and the security forces violently suppressed dissent. Still, Indonesia’s human rights record since 1998 has been mixed. Military and police forces did not fully accept civilian control over their actions and still act with impunity. New legal restrictions were also placed on civil society. And the brutal legacy of Suharto’s rule remains unexamined.

Indonesia’s human rights record since 1998 has been mixed. Military and police forces did not fully accept civilian control over their actions and still act with impunity. New legal restrictions were also placed on civil society.

Freedoms of speech, association and religion are generally respected, but significant problems remain in each area. Independent media has frequent criticism of the government and regular reporting on corruption, abuses by security forces and other issues. Regulatory restrictions, however, force many broadcast media to operate outside legal protection, causing self-censorship by journalists. As in Singapore (see Country Study), defamation laws are used to protect vested interests, also resulting in self-censorship. Transparency laws guarantee freedom of information, but the government still shields the security services and corrupt agencies. Violence is ongoing against journalists, especially in regions affected by separatist and terrorist groups.

Independent trade unions represent 10 percent of the registered workforce and have the right to strike, except for public sector employees. Indonesia’s adoption of ILO conventions and the National Action Plan for Business and Human Rights (see Resources) subject foreign investors to international labor standards. Still, abuses at foreign-owned firms often go unchallenged and there is weak enforcement of child labor and minimum wage laws.

Civil society is active, with around 49,000 registered organizations. Citizens’ groups petition the government on significant issues. Many report human rights violations to the government’s monitoring office. A law passed in 2013, however, was a step backward. It requires NGOs to adhere to the national ideology of Pancasila (see above). Under the law, the government oversees NGOs’ compliance and may dissolve organizations committing blasphemy or advocating banned ideologies, such as atheism and communism.

Under the law, the government oversees NGOs’ compliance and may dissolve organizations committing blasphemy or advocating banned ideologies, such as atheism and communism.

Freedom of religion is guaranteed in the constitution, but Human Rights Watch reports that regional and local governments frequently discriminate and harass minority religions, especially non-Sunni sects. Worship is restricted by denying permits to build churches and mosques. There are also frequent attempts by religious authorities to prevent “blasphemous” events (one event banned was a scheduled concert by Lady Gaga in Jakarta).

Muslims, who are the large majority, must submit to Sunni Shari’a courts or be subject to court action. As already noted, atheism is not recognized as a legitimate belief and blasphemy is outlawed (see article in Resources).

Continuing Concerns

Abuses by police and military forces have been ongoing sources of concern for human rights advocates.

Abuses by police and military forces have been ongoing sources of concern for human rights advocates. For example, government counterinsurgency forces in Aceh province tried to undermine the peace agreement reached between President Megawati and the GAM separatist movement in 2004. In other regions where there are autonomy or separatist movements, such as Papua, security forces have carried out extra-judicial killings, other violence, warrantless arrests and torture. At the same time, the special anti-terrorist security force has been praised for effectively preventing terrorist bombings since a major attack on a resort in Bali in 2004. It has pursued cases against groups associated with al Qaeda and Islamic State, both of which carried out several gruesome attacks.

Current Issues

In April 2019, Indonesia held its fourth national presidential and parliamentary elections under constitutional provisions established after 1999.

The office of president and vice president, all 560 seats in the House of Representatives, all 132 seats in the Senate, as well as 2,112 assemblymen in 33 regions and almost 17,000 legislators at the district level were all contested.

The office of president and vice president, all 560 seats in the House of Representatives, all 132 seats in the Senate, as well as 2,112 assemblymen in 33 regions and almost 17,000 legislators at the district level were all contested in free and fair elections. Turnout of the country’s 191 million registered voters was reported at 83 percent (the highest since 1999). Despite ongoing threats of violence, balloting at 550,000 polling stations remained generally peaceful. Both international and domestic observers reported free and fair conditions.

In the parliamentary elections, the Democratic Party of Indonesia-Struggle (PDI-P), still led by Megawati Sukarnoputri, won a plurality of 19 percent of the vote (128 seats). Golkar, the former government party now led by a billionaire mogul, won 12 percent (85 seats). The nationalist Just and Prosperous Indonesia Party (Gerindra), which had split from Golkar in 2008, also won 12 percent (78 seats). The two main Islamic parties retained their fourth and sixth positions in parliament, at around 9 percent. A new party was fifth and the Democrat Party of former President Yudhoyono dropped to seventh with 8 percent.

In the presidential race, The PDI-P candidate, Joko Widodo, known popularly as Jokowi, won re-election as president. He received 55 percent of the vote in a rematch with Gerindra’s leader, Prabowo Subianto, the former general and son-in-law of Suharto.

Indonesia’s capital, Jakarta, on its most populous island, Java, has a population of 11 million. Due to climate change, the port city, its skyline shown here, is sinking and faces large challenges to adapt. Consistent with his infrastructure focus, President Joko Widodo got parliament to approve moving the capital to the planned city of Nusantara on Borneo, Indonesia’s largest island.

After taking office first in 2014, Jokowi had adopted major political and economic reforms, education initiatives and a large infrastructure and investment program that maintained economic growth at around 5 percent annually. Among the largescale projects is moving the capital from Jakarta, which is sinking due to higher sea levels from climate change, to a planned city called Nusantara on the island of Borneo. But Widodo disappointed followers by letting Golkar join the government to form a majority coalition. In his second administration, Widodo further distanced himself from his own party, PDI-P, and appointed his rival from the Gerindra party, Prabowo Subianto, as defense minister.

Indonesia under Widodo’s ten-year presidency had a declining human rights record. In his first administration, he appointed as head of the police someone under investigation for corruption; he tolerated repressive security force actions in Papua, where indigenous Papuans seek autonomy; and he oversaw executions of eight foreign nationals convicted of drug trafficking. (The last action caused several countries to suspend diplomatic relations.) The record did not improve in his second administration. Overall, Freedom House reduced Indonesia’s freedom ranking by more than 10 points, especially in the area of civil liberties. This decline takes Indonesia further away from the “free” category it had achieved from 2006-2013 to the solidly “partly free” category.

[T]he parliament’s large representation by nationalist and Islamist parties has resulted in new harsh legislation.

One reason is that the parliament’s large representation by nationalist and Islamist parties resulted in new harsh legislation. An amended criminal code outlawing blasphemy, defamation and insults of government institutions were used against 332 people from January 2019 to May 2022 according to Amnesty International (see Resources). At the same time, the parliament’s pluralist character resulted in a bill against gender violence that criminalizes sexual harassment, forced marriage, forced sterilization, sexual torture, sexual slavery and online sexual violence.

Academic freedom was restricted. Similar to a 2013 law governing NGOs (see Human Rights above), a presidential declaration in 2021 governing universities declared that research and innovation policy be guided by Pancasila, the state ideology. Also, students and student union leaders have been arrested for involvement in protest over suppression of the Papua separatist movement. Professors have been charged with defamation and removed from their posts for criticism of public officials. Self-censorship in teaching is now the norm.

There remained ongoing concerns for media freedom, with reports of physical or other attacks as well as self-censorship due to defamation suits. Also, in 2023, the parliament approved new provisions on criminal defamation for digital media. As well, Freedom House also reported increasing discrimination of Papuans and LGBTQ+ persons. The latter are often subject to attacks by hardline Islamist groups.

Nearing the end of his presidency, Joko Widodo, who was constitutionally barred from a third term, formed a political alliance with his former rival, Prabowo Subianto. His larger aim is to establish his own party and political dynasty. To do so, Widodo endorsed Subianto in his third run for the presidency in exchange for having his son, Gibran Rakabuming Raka, as his vice-presidential candidate. Raka, at 36, did not meet the age requirement of 40 but was allowed to run due to a judicial ruling by a political appointee that held that another requirement — prior election to a local post — superseded the age requirement.

The 2024 national election saw a worrisome manipulation of both the judiciary and the electoral administration in allowing President Widodo’s son to run for the vice presidency despite not meeting the age requirement and in taking other favorable actions for Widodo's favored presidential candidate, Prabowo Subianto..

In the election campaign, Subianto softened his image running as an elder “grandfather” and as a bridge to the next generation. With Widodo’s son on the ticket, Subianto succeeded in his third try for the presidency. In the national election, held in February 2024, he won 58 percent of the vote against an independent candidate endorsed by a coalition of three parties and the PDI-P candidate. They received 25 percent and 16 percent of the vote, respectively.

The elections for the 580-seat House of Representatives saw similar fractured results as in 2019. The PDI-P won a small plurality at 17 percent and Golkar improved to 15 percent. Despite Subianto’s decisive victory, his party, Gerindra, saw no marked improvement at 13 percent. The two Islamist parties won 10 and 8 percent, as previously. The National Democratic Party, whose media magnate leader had recently been arrested on corruption charges, and the Democratic Party of former President Bambang Yudhoyono, won 69 seats and 44 seats. (None of the nine other parties competing won seats.)

Since 1999, Indonesia has transformed itself from a hardened dictatorship to an electoral democracy with regular, free and fair elections that have wide-ranging political competition. There has also been adoption of international human rights standards. No party dominates at the national, regional or local level, ensuring a strong multiparty system. The country’s path since 2014, however, has seen a slow backsliding in political rights and civil liberties and the 2024 national election saw a worrisome manipulation of both the judiciary and the electoral administration in allowing President Widodo’s son to run for the vice presidency despite not meeting the age requirement and in taking other favorable actions for Widodo's preferred presidential candidate, Prabowo Subianto.

The content on this page was last updated on .