Summary

Map of Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan lies at the crossroads between Europe and Asia. Located on the coast of the Caspian Sea, it has been influenced from all directions: Arabia, the Caucasus, Central Asia, Iran, the Ottoman Empire and Russia. Today, it is formally a republic with a unitary presidential system that functions as a consolidated dictatorship.

Having a long history of occupation and domination by foreign powers, Azerbaijan declared independence with the collapse of the Russian Empire and formed the first democratic republic in the Muslim world. It lasted only from 1918 to 1920. The Bolshevik Red Army reconquered Azerbaijan and it was incorporated into the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.

As the Soviet Union was fracturing, Azerbaijan declared independence in October 1991 and again enjoyed just over one year of democratic rule before returning to dictatorship. In 1993, the former secret police chief and first secretary of the Soviet republic’s Communist Party, Heydar Aliyev, seized power after a military insurrection, backed by Russian forces. Ever since, the country has been controlled by the Aliyev family, with Heydar succeeded as president by his son in 2003 in fraudulent elections. While elections are regular, none since 1994 have been free or fair. Police repression, intimidation and control over the electoral process have ensured that the Aliyevs maintained political control.

Azerbaijan is a small country in area (112th in the world in size at 86,600 square kilometers). Its population of 10.3 million people is ranked 93rd as of 2023. Despite the country's large oil and gas reserves, the country does not rank highly in the world’s economy. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) ranks Azerbaijan 82nd in the world in projected nominal GDP for 2024 (around $80 billion in total output). Per capita gross national income is projected to be $7,641 per annum, ranked 90th. There is a high level of disparity of income between urban and rural populations.

History

From First Kingdom to the 20th Century

The first formed state on Azerbaijani territory was the Kingdom of Mannae, which ruled from the 10th to the 8th centuries BCE. Thereafter, Azerbaijan became the subject of repeated invasion, occupation and foreign influence.

The Persian leader Cyrus the Great conquered the territory in the sixth century BCE, followed by Alexander the Great in the mid-4th century and subsequent imposition of the Seleucid dynasty. An independent kingdom existed for two centuries before parts of the territory were conquered in turn by the Armenians, the Romans (in the first century BCE) and the Persian Sassanid Empire (in the fourth century CE).

The first formed state on Azerbaijani territory was the Kingdom of Mannae, which ruled from the 10th to the 8th centuries BCE. Thereafter, Azerbaijan became the subject of repeated invasion, occupation and foreign influence.

Azerbaijan was seized in the Arab conquests in the 7th century CE and most Azeris converted to Islam. In the mid-11th century, the Oghuz Turks expanded the Seljuk Empire from Central Asia to Anatolia and took over much of Azerbaijan. They introduced the current language, customs and Turkic identification of the Azeri population. Azerbaijan fell to the Mongol army, as did much of Asia in the 13th and 14th centuries. When Mongol rule waned, the territory came under the control of the Safavid dynasty in Persia. In 1501 CE, the Safavids formally adopted Shi’a Islam as their ruling theology, which was generally adopted by Azeris and others under Persian influence (most of the Turkic world remained Sunni).

Beginning in the early 18th century, Russia and a revived Persia vied for Azeri territory. It was formally divided in treaties signed in 1813 and 1828. Northern Azerbaijan, corresponding to the country’s current borders, came under Russian control. Exploitation of oil began in the 1870s, which led to a period of economic modernization. Baku, the capital, of Azerbaijan, became an important economic center before World War I and it was renowned for its cosmopolitan and diverse society, including a large Jewish minority. Southern Azerbaijan remained under Persian control and was incorporated into present-day Iran, where two thirds of Azeri-speaking people now live.

The First Democratic Republic in the Muslim World

The overthrow of the Russian tsar in 1917 and the end of World War I in 1918 offered northern Azeris the opportunity to establish their long-held aspiration of national independence. The Azerbaijan Democratic Republic was established in 1918 under the leadership of Mahammad Amin Rasulzade, who had created the Musavat Party in 1911 on a platform of Western liberal values. From 1918-20, Azerbaijan was the first and at that time the only democracy in the Muslim world. A liberal constitution was adopted instituting a parliamentary system of government and protections for basic freedoms. The constitution also adopted universal suffrage, extending the right to vote to women before many states in Europe and the Americas.

Mahammad Amin Rasulzade, shown at left in 1924, led the first Azerbaijan Democratic Republic from 1918-20. Following the Soviet takeover, Musavat Party leaders were arrested but some, like Rasulzade, escaped to exile in Turkey.

The Long Soviet Nightmare

The Azerbaijan Democratic Republic lasted for only two years. Buffeted by the turmoil of the Russian Civil War, the government collapsed and the Bolshevik Red Army seized control of the republic in April 1920. In 1922, Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia were joined together as the Transcaucasian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic and incorporated within the Soviet Union. In 1936, the three countries were made separate Soviet Socialist Republics.

The 70-year period of Soviet rule was severe. Musavat’s leaders and activists, and many thousands of ordinary citizens, were imprisoned and often perished in prison and labor camps.

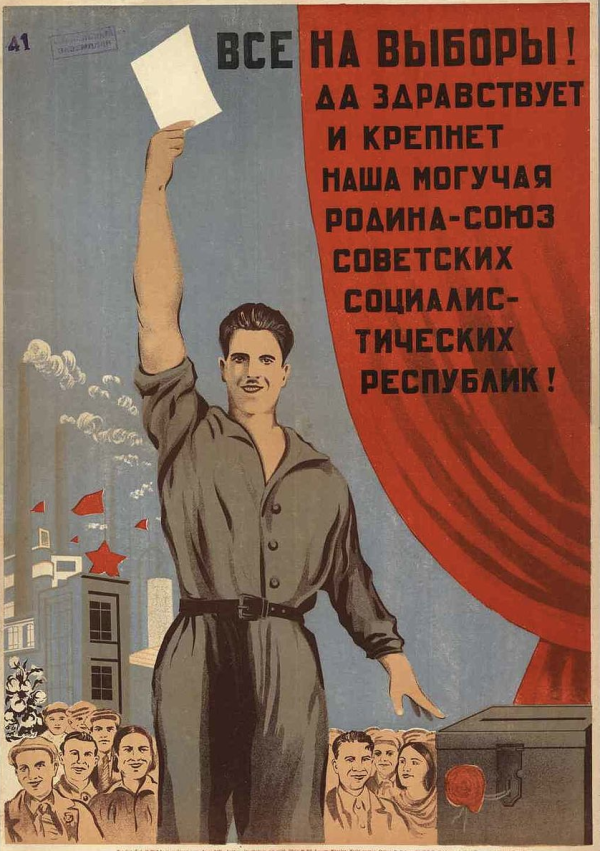

The 70-year period of Soviet rule was severe. Musavat’s leaders and activists, and many thousands of ordinary citizens, were imprisoned and often perished in prison and labor camps. Tens of thousands more were deported to Central Asia and Siberia, where they often did not survive the harsh conditions. All property was seized and collectivized. Every aspect of life came under the control of the Communist Party and the KGB secret police. So-called “elections” were held routinely, but only to force citizens to vote for the Communist Party, which held supreme power under the Soviet Constitution.

Musavat leader Mahammad Amin Rasulzade was initially imprisoned but later escaped to Turkey. There and elsewhere in Europe he led anti-Soviet and anti-Fascist political movements in exile. Back in Turkey, he reformed Musavat with other ex-patriots in exile, where it continued to organize opposition to Soviet rule.

The Collapse of the Soviet Union and the Restoration of Independence

Elections in the Soviet Union were controlled to allow only approved Communist Party candidates. A 1939 Azerbaijan election poster.

By 1988, the Soviet Union was fraying. Communist General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev had adopted the reform policies of glasnost and perestroika to try to stem the USSR’s economic and political decline. Taking advantage of the openings these policies allowed, Azeris and other nationalities throughout the Soviet Union formed national popular front movements to push for greater autonomy and then independence. The leaders of the Azerbaijan Popular Front, who had been active in the dissident movement, based the Popular Front platform on the original Musavat Party and its liberal heritage.

The national movement in Armenia sparked a separatist movement in Nagorno-Karabakh, an autonomous republic within the Azerbaijan SSR. It had a majority Armenian population that sought union with Armenia despite not having a contiguous border.

Until 1988, Azerbaijan had a diverse population, with large Armenian and Russian communities and other minorities, while many Azeris also lived in Armenia. Attacks by both Azeris and Armenians against members of the other group resulted in mutual flight of the communities across borders. Central Soviet authorities used the pretext of ethnic conflict to crack down on national protests for independence and imposed martial law in the Azerbaijan SSR in January 1990.

Under Soviet elections held in 1990, Azerbaijan's Supreme Soviet was dominated by Communists, but some opposition members had gained seats and succeeded in convincing a majority to declare autonomy. On the other hand, Ayaz Mutalibov, the Azerbaijan Communist Party general secretary, was one of two republic leaders to back the failed August 1991 coup attempt in Moscow against Mikhail Gorbachev aimed at preserving the Soviet Union.

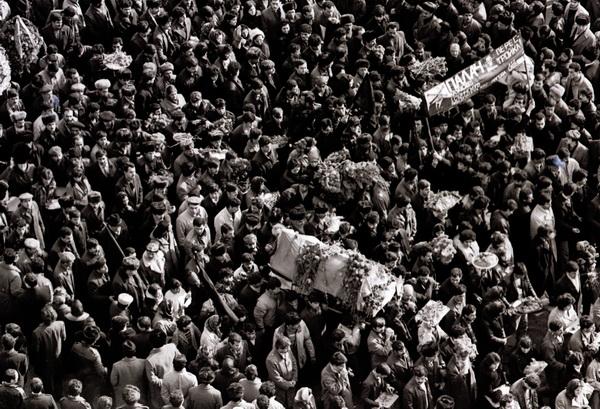

Soviet authorities tried to repress mass demonstrations for independence with a harsh crackdown in 1990, known as Black January. Above, an Azerbaijan Popular Front funeral procession of 500,000 protested the mass killings by Soviet troops. Creative Commons License. Photo by Azerbaijan State News Agency.

In the face of mounting demonstrations organized by the Azerbaijan Popular Front, Mutalibov quickly reversed course. To preserve his power, Mutalibov dissolved the Azerbaijan Communist Party and held a snap single-candidate presidential election that September. With growing public support for the Azerbaijan Popular Front, the Supreme Soviet now issued a declaration of Independence on October 18. The decision was overwhelmingly ratified by public referendum in December 1991.

Mutalibov became the first president of independent Azerbaijan by default. In December 1991, the Nagorno-Karabakh National Council also declared independence, initiating a full-scale war between Armenian and Azeri forces in which the Russian Federation sided with Armenia. The conflict, which ultimately cost thousands of lives and displaced tens of thousands more, would have a profound impact on the future politics of Azerbaijan.

The period of Azerbaijan’s independence is described in the next section.

Free, Fair and Regular Elections

Azerbaijan . . . established the first democratic republic in the Muslim world in 1918 and adopted a constitution with universal suffrage.

Azerbaijan, having little history of sovereignty and dominated for most of its history by foreign powers, established the first democratic republic in the Muslim world in 1918 and adopted a constitution with universal suffrage. But the democratic republic survived only two years before the Bolshevik Red Army conquered Baku in April 2020 and Soviet communist rule was imposed. No free elections were held for 70 years.

The Azerbaijan Popular Front (APF), inspired by the legacy of the Democratic Republic, successfully pressed the Soviet parliament to declare independence in October 1991, which was approved overwhelmingly in a popular referendum in December. Azerbaijan again enjoyed only a brief period of democracy in 1992-93. A coup by a former KGB chief and Soviet Politburo member established a dictatorship similar to those in other post-Soviet republics (see also Country Studies of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan).

Azerbaijan's Second Period of Democracy

The new independent state declared in October 1991 was at first ruled by the former communist leader Ayaz Mutalibov and a ruling national council he appointed. Through continued mass protests, the Azerbaijan Popular Front movement succeeded in pressuring the national council to call a new presidential election for June 7, 1992.

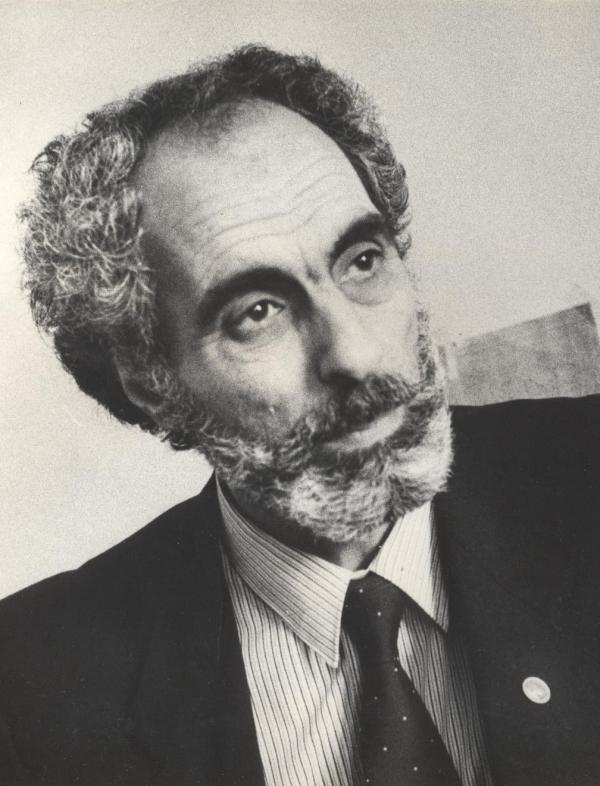

Abulfaz Elchibey, a long-time Soviet dissident who led the Azerbaijan Popular Front, was elected president of Azerbaijan in 1992. He was forced to resign a year later in a military coup.

Abulfaz Elchibey, a former Soviet dissident and founder and chairman of the Popular Front, won Azerbaijan’s first free presidential election with 61 percent of the vote against four candidates. No parliamentary elections were held but a new national parliament, or Mejlis, was formed based on existing membership in the Supreme Soviet, which now included a majority of Popular Front and other opposition members.

Elchibey and the Popular Front adopted the liberal ideology of Azerbaijan's earlier independence leader, Mahammad Amin Rasulzade (see above). As in the Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan, the Mejlis adopted legislation guaranteeing freedom of expression, assembly and association and liberalizing the economy. In this free environment, an independent media emerged and other new parties, unions and public associations were formed. The new speaker of the parliament, Isa Gambar, re-established the Musavat Party and was elected Musavat’s first chairman. In foreign policy, Elchibey negotiated the withdrawal of Russian military forces in Azerbaijan, the first post-Soviet republic to do so.

The Return to Dictatorship

Azerbaijan’s second democratic moment was brief, as in 1918-20. . . . Heydar Aliyev, a former head of Azerbaijan’s secret police and member of the USSR’s Politburo, seized power as interim president. Aliyev allowed only token opposition for an election in October 1993 to affirm his position.

Azerbaijan’s second democratic moment was brief, as in 1918-20.

President Elchibey was unable to resolve the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict or stem losses against Armenian forces (one-fifth of Azerbaijani territory was seized for a land-corridor to the separatist republic). In June 1993, just one year after his election, he faced a military insurrection led by a former Soviet commander backed by Russia. To forestall bloodshed, Elchibey fled to his home region of Nakhichevan in eastern Azerbaijan.

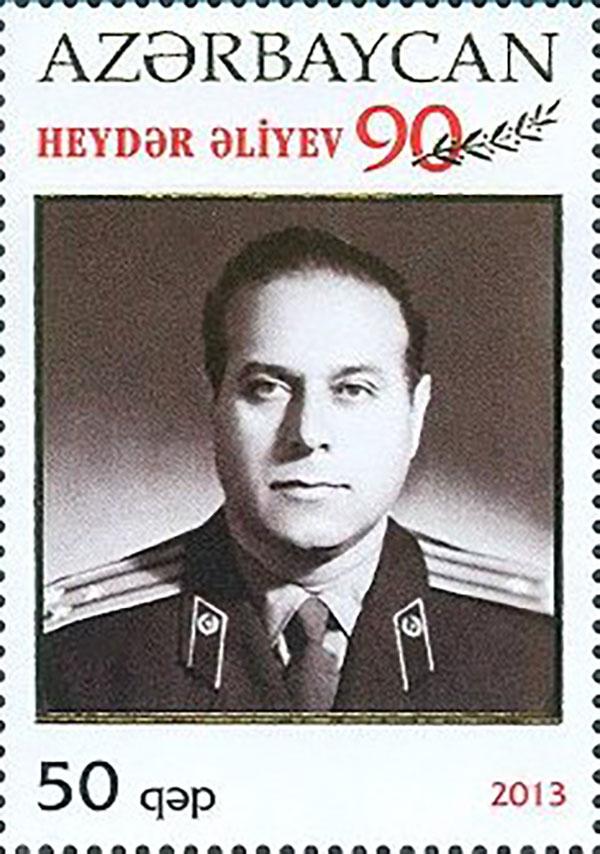

Heydar Aliyev, a former head of Azerbaijan’s secret police and member of the USSR’s Politburo, seized power as interim president. Aliyev allowed only token opposition for an election in October 1993 to affirm his position. He claimed a Soviet era-style 98 percent of the vote and then asserted control over parliament, broadcast media, and the security services, which he used to repress opposition parties, independent newspapers and trade unions.

Heydar Aliyev, a former Soviet Politburo member and head of the Azerbaijan Communist Party, came to power in a military coup in 1993. He began his career as a colonel in the Soviet secret police, which was celebrated in a 2013 postage stamp.

Parliamentary elections were held only in November 1995 together with a referendum on a new constitution that institutionalized centralized presidential power. Opposition parties competed in completely unfair conditions. The government's Central Election Commission (CEC) disallowed 63 percent of the candidates who petitioned to run. Musavat leaders were arrested or barred from traveling outside the capital. Election activities and rallies were disrupted by police. With the CEC controlling voting procedures and counting, Aliyev's New Azerbaijan Party “won” a large majority of the legislative seats. The referendum passed with 91 percent of voters reported in favor.

Musavat and other political parties boycotted the 1998 presidential election to protest an undemocratic electoral law that provided no safeguards for a free and fair ballot. Aliyev was declared the winner, although this time with just 75 percent of the vote. While international monitors determined that the election process was unfair and that elections did not meet international norms, Western governments nevertheless recognized Aliyev’s re-election.

An Opposition Challenge to the Regime

Although conditions remained unfair, opposition parties decided to compete in the November 2000 parliamentary elections. In the face of government repression, an opposition coalition led by the Musavat Party carried out a vigorous campaign. Mass rallies indicated widespread support for the opposition. But control over the electoral process again determined the result: the New Azerbaijan Party was declared the winner with only a few opposition members allowed seats. International monitors observed ballot box stuffing, ballot manipulation, a flawed counting process and restrictions on domestic observers. An independent alternative count indicated that the democratic coalition had in fact won a majority of votes cast.

Elections “Must Be Described by a Different Term”

Heydar Aliyev arranged a rigged referendum in 2003 to amend the constitution in order to arrange his successor. He was thus able to appoint his son, Ilham, as prime minister and resign as president in favor of Ilham. The son then replaced his father on the ballot for the presidential election held that October.

In 2003, supporters of the democratic candidate for president, Isa Gambar, protested fraudulent presidential elections and were beaten by police. Photo Courtesy of Institute for Democracy in Eastern Europe (IDEE).

The main opposition candidate was Musavat leader Isa Gambar, running as the single candidate of a coalition that included all opposition parties. Again, government control over broadcast media and police repression tried to limit outreach. Nevertheless, the opposition coalition succeeded in carrying out an effective campaign culminating in huge electoral rallies attended by hundreds of thousands of supporters.

On election day, October 15, the Central Election Commission quickly declared Ilham Aliyev the official victor with a supposed 77 percent of the vote. It claimed Gambar had received just 14 percent. Tens of thousands of demonstrators took to the streets of Baku to protest the clearly fabricated results and the stealing of the election. These were put down with brutal force. Following the protests, more than 700 opposition activists were arrested and many sentenced to harsh prison terms. International observers from the Institute for Democracy in Eastern Europe concluded that "if the word 'elections' is to retain its meaning, the events of October 15 in Azerbaijan must be described by a different term" (see Statement in Resources).

The Further Consolidation of Dictatorship

Parliamentary elections in both November 2005 and 2010 were even more rigged than previously. The democratic opposition, battered by repression and fractured as a result of infiltration and police manipulation, could not mount as serious a challenge as in 2000 or 2003. The regime no longer felt the need even for token opposition members of parliament.

In 2008, Ilham Aliyev handily “won” presidential elections against marginal candidates, supposedly with 87.5 percent of the vote. He then pushed through a referendum removing the two-term limit for the presidency and thus the last remaining constitutional limitation on his rule. He ran for another five-year term in an election held in October 2013, with a purported 84.5 percent vote in favor. A united opposition candidate, Jamil Hasanli, a well-known filmmaker, ran in the race but was allowed to tally just 5.5 percent.

Heydar Aliyev’s son, Ilham, succeeded his father as president in 2003 through fraudulent elections. He has consolidated a personal dictatorship through pervasive repression and widespread corruption. Above, being interviewed by Euronews. Creative Commons License. Photo distributed by President.az.

International observers from the OSCE stated the election “was undermined by limitations on freedoms of expression, assembly and association, . . . voter intimidation and a restrictive media environment.” The mission also documented “widespread irregularities, including ballot-box stuffing and . . . fraudulent counting.”

In 2018, Aliyev ran for a seven-year term, under terms of an amended constitution adopted in 2016. An amendment also allowed the president to name a vice president; Aliyev named his wife to the post in 2017. In the presidential election, the official tally for Aliyev went up to 86.02 percent.

Current Issues

In all of Azerbaijan's elections since the 1993 coup, government control over electoral procedures, the state media and, not least, the police denied any possibility of free or fair elections.

In all of Azerbaijan's elections since the 1993 coup, government control over electoral procedures, the state media and, not least, the police denied any possibility of free or fair elections.

While Heydar Aliyev, the ex-Soviet communist party and KGB chief, put in place the basic features of Azerbaijan’s dictatorship, his son Ilham has successfully institutionalized and extended its repressive features. Civic groups and political parties continue to oppose the government and press for democratic change and human rights. But their members are increasingly marginalized — put in jail, harassed or forced into exile. The space for open criticism and activity has greatly narrowed.

In December 2023, Ilham Aliyev called a snap presidential election for February 2024 (it was scheduled for 2025). Aliyev wanted an early election to claim popular support for his military campaign to retake the Nagorno-Karabakh region (see below). In this election, Aliyev was awarded 92 percent of the vote by the official count. There was no serious opposition candidate (an independent was allotted 2 percent). On re-election, Aliyev renamed his wife, Mehriban Aliyeva, as vice-president.

Aliyev also had the parliament call an early election for September 1, again as affirmation of retaking Nagorno-Karabakh. Not surprisingly, the New Azerbaijan Party "won" 68 out of 125 seats (the remainder went to so-called independents who are in fact tied to the ruling party). The observer mission of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe concluded: "The early parliamentary elections took place in a restrictive political and legal environment that does not enable genuine pluralism and resulted in a contest devoid of competition."

Aliyev's consolidated dictatorship has resulted in ever-increasing levels of repression and corruption. Starting in 2009 with the passage of a law on NGOs that placed restrictions on receiving foreign money, the government steadily increased repression on civic associations, independent trade unions and political parties. The regime put in jail many of the country’s most well-known civic and human rights defenders.

A demonstration of the National Council of Democratic Forces in January 2019 calling for the release of independent journalist and human rights activist Mehman Huseynov and other political prisoners. Photo by Voice of America.

There is effectively no independent media. Only small newspapers and internet sites operate and even then many journalists and analysts from independent outlets are imprisoned. A journalist for Radio Free Europe, Khadija Ismailova, was sentenced to 7½ years’ imprisonment in September 2015 for her articles reporting on the vast wealth and corruption of the Aliyev clan and his government supporters (see below). While released in 2016, her movements are strictly regulated. Many other journalists and political activists remain in prison.

The cumulative effect of repression has taken a toll on the opposition. Thousands of Musavat Party and other activists who have been imprisoned since 1995 are generally denied work and remain unemployable. “They have given up everything to defend democracy,” Arif Hajili, a recent chairman of the Musavat Party, has stated. In late 2023, in preparation for the snap presidential election, the Mejlis passed a law changing requirements for political party registration, now requiring 5,000 enrolled members instead of 1,000. The intent was clearly to shut down any smaller parties.

As Freedom House reported in its 2024 Country Report of Azerbaijan, “The authoritarian system in Azerbaijan excludes the public from any genuine and autonomous political participation. The regime relies on abuse of state resources, corrupt patronage networks, and control over the security forces and criminal justice system to maintain its political dominance.”

"The authoritarian system in Azerbaijan excludes the public from any genuine and autonomous political participation. The regime relies on abuse of state resources, corrupt patronage networks, and control over the security forces and criminal justice system to maintain its political dominance."

Freedom House 2024 Azerbaijan Country Report

Corruption is pervasive and the Aliyev family and its associates have amassed huge private fortunes (including large property holdings in London and elsewhere). The regime has also used confiscated resources for a bribery scheme (termed “caviar diplomacy”) to influence the Council of Europe, the European Union and other bodies so that they do not strongly criticize or sanction the regime for its human rights record. (See article in The Guardian in Resources.)

As a result, there is little criticism of Azerbaijan by European institutions or the U.S. government despite the regime’s high level of repression. Another reason is the recent demand for energy by the EU due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. EU countries made new agreements to increase oil and gas deliveries from Azerbaijan. Azerbaijan was then selected as the host of the November 2024 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP29).

The economic situation remains dire for most of the population. Oil and gas revenues have largely gone towards construction of large modern buildings in Baku. Much of the capital’s old neighborhoods and 19th century architecture has been destroyed.

Energy profits also went towards increasing military capability, including large drone purchases from Turkey. These were used in two offensives, first in 2020 and then a more decisive one in 2023, to retake the Nagorno-Karabakh region and the Lachin Corridor in 2020 in 2023. Nagorno-Karabakh's previous separate state institutions were dissolved and nearly the entire ethnic Armenian population fled to Armenia. Following the successful military campaign, the authorities mounted another crackdown on independent media. Several journalists and media leaders were arrested on various bogus charges due to their reporting on the offensive and its impact on the local population.

The content on this page was last updated on .