Lawless Rule

As with consent of the governed, to understand the essential principle of rule of law, it is useful to examine when it is absent. One example is the experience of the Crimean Tatars, a small Turkic Muslim group that originally settled on the Crimean peninsula on the Black Sea in the 14th century. They then came under subjugation first by rule of the Russian Empire in the late 18th century and then of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) in the 20th century.

To understand the essential principle of rule of law, it is useful to examine when it is absent. One example is the experience of the Crimean Tatars, a small Turkic Muslim group that originally settled on the Crimean peninsula on the Black Sea in the 14th century.

During World War II, many Crimean Tatars loyally joined the Red Army in the Soviet Union's battle against Nazi Germany. During the course of the war, however, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin grew paranoid of the Tatars' loyalty. When the Soviet Red Army retook the Caucasus and then Crimea, Stalin ordered the deportation of the entire Crimean Tatar population to Central Asia.

On May 18, 1944, the Soviet secret police (at the time known as the NKVD) began rounding up all Crimean Tatars and deported them by train to the Soviet republics of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. Within three days, 238,500 Tatars were exiled. A third to half of those who were forced from their homes died from hunger, exposure and disease. Stalin's regime undertook similar actions against other historical minority communities in the Caucasus.

As the Soviet Union was weakening in the late 1980s, Crimean Tatars organized to return to their homeland, which by then had been made part of the Republic of Ukraine as a contiguous territory. Two hundred and fifty thousand Crimean Tatars returned over the next decade as Ukraine gained independence. Today, however, they again face harsh repression and partial forced exile. In 2014, Vladimir Putin’s Russian Federation occupied and then illegally annexed the territory. Repression increased after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

The ethnic cleansing and repression campaigns of Crimean Tatars are examples of the rule of lawlessness — the exercise of arbitrary power without constraint. Unfortunately, there are many such examples in history.

On May 18 each year, Crimean Tatars memorialize the date in 1944 of their mass deportation to Central Asia. In 2016, at a new monument in Kyiv, Ukraine, Crimean Tatars marked the day with that of another period of repression starting in 2014, when the Russian Federation occupied and illegally annexed the peninsula. Creative Commons. Photo by Visem.

A Necessary Democratic Principle

In democracies, constitutional limits on power require the adherence of state authority to a country's constitution and laws as adopted by the people’s elected representatives and overseen by an independent judiciary. This is the meaning of the oft-cited phrase "a government of laws, and not of men" (it was originally used in the 1780 Constitution of Massachusetts).

In democracies, constitutional limits on power require the adherence of state authority to a country's constitution and laws as adopted by the people’s elected representatives and overseen by an independent judiciary.

Under such a system, the rule of law is supreme to the authority of any individual. It is an essential check on political power when used against people's rights and an essential instrument for fulfilling laws adopted by the people’s representatives. Democracy could not survive without the regulation of state power by a system of law and institutional practices exercised by courts. And just as the rule of law protects the majority from arbitrary power and tyranny, it must protect the minority from arbitrary power and "tyranny of the majority" (see also "Majority Rule/Minority Rights").

Some revolutionary thinkers extol anarchism, or the absence of governing authority, as the highest form of justice. Without state authority, it is believed, there is no need for a coercive system of state law. In reality, the absence of state authority and rule of law leads to mob rule, violence and chaos. This in turn has generally given rise to dictatorship and the exercise of arbitrary power. As Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter wrote in discussing the rule of law: “If one man can be allowed to determine for himself what is law, every man can. That means first chaos, then tyranny.”

The Rule of Law Has Differing Principles

Much of what Americans consider to be the rule of law is derived from Anglo-Saxon legal traditions (see History). But there are many variations in how countries organize legal and political institutions and apply the rule of law. These differences can be confusing when talking about basic principles.

Democracy could not survive without the regulation of state power by a system of law and institutional practices exercised by courts.

For example, the principles of "innocent until proven guilty," the right not to incriminate oneself, and trial by a jury of one's peers are so deeply ingrained in the fabric of American and British law that they are considered by society to be absolute. And, indeed, they are essential principles. Yet continental Europe, most of which follows a Roman law tradition, does not operate by the same tenets. The French legal system even has the presumption of guilt over innocence and allows indefinite periods of incarceration. These practices violate American and British standards, but do not mean that France does not operate by the rule of law. Other principles apply.

Common Definitions

Still, the adoption and practice of some basic principles of the rule of law are clear barometers for the practice of democracy. While there is no set definition of the rule of law encompassing all of its characteristics, the scholar Rachel Kleinfeld, examining different traditions, set out to identify common standards (see Resources). She identified five:

- A government bound by and ruled by law;

- Equality before the law;

- The establishment of law and order;

- The efficient and predictable application of justice; and

- The protection of human rights.

These principles are common sense. A government that is not bound by its own laws is by definition lawless. Without equality before the law, the rule of law has meaning only for a select group or individual. Without political or social order, the law cannot be applied. If the law is neither efficient nor predictable no one can trust its application nor abide by its rules.

The standard that the rule of law must protect human rights was not always accepted. It became an obvious precondition for any democracy that establishes human rights as foundational in its constitution as the United States and France did after their Revolutions and as now all functioning democracies do.

Current and historical deviations from the rule of law in democracies . . . have made evident the importance of fulfilling principles of rule of law, not a reason for invalidating them.

One might add a sixth common principle: in a democracy, there should be separation of religion and state. Religious institutions may establish law within their own community to abide under principles set by that religion, and these may even govern civil matters like marriage and domestic disputes.

But when one religion is imposed on all communities, there is generally domestic repression as well as foreign conflict. The Huguenot Rebellion in France and the European Wars of Religion (beginning in 1517) are historical examples (see History). A current example of domestic repression is Saudi Arabia (see Country Study in this section).

There are often contradictions in principle or practice in democracies. These do not negate the rule of law’s essential importance nor its common standards. Rather, the consequences of the breakdown of the rule of law in dictatorships — as in the account above or the example of Nazi rule in Germany — make self-evident the importance of adhering to rule of law principles. Current and historical deviations from the rule of law in democracies (such as slavery, systematic discrimination, displacement of Indigenous populations, or the unequal treatment of women, among others) have also made evident the importance of fulfilling principles of rule of law, not a reason for invalidating them (see also Country Study of Germany in this section and “The Breakdown of Law” below),

Institutions of the Rule of Law

Rachel Kleinfeld Belton also identifies the necessary institutions of the rule of law. These include:

- A set of comprehensive laws or a constitution based on popular consent;

- A functioning judicial system; and

- Established law enforcement agencies with well-trained, professional officers.

A constitution or set of laws without legitimacy or acceptance will not be respected by the people. A legal system that does not guarantee the rights of the people cannot have legitimacy.

Absent any of these institutions, the rule of law may arguably break down. Again, these are also common sense principles. A constitution or set of laws without legitimacy or acceptance will not be respected by the people. A legal system that does not guarantee the rights of the people cannot have legitimacy. If there is no functioning judicial system to check the misuse of power, corrupt law enforcement agencies can manipulate the laws for arbitrary use and self-interest. Law enforcement agencies and courts must have professional competence to fulfill their responsibilities; otherwise, they may abuse their offices and the rights of the people.

The Evolution of Law

Another factor is needed for the rule of law: the will of society to pursue basic principles such as liberty, equality and due process. Such will must then be joined by the judgement of jurists to uphold these principles when violated in practice.

Another factor is needed for the rule of law: the will of society to pursue basic principles such as liberty, equality and due process. Such will must then be joined by the judgement of jurists to uphold these principles when violated in practice.

An example is the case Somerset v. Stewart in late 18th century England. James Somerset, an enslaved person, escaped captivity when taken to London. On his freedom, he sought baptism as a Christian. Months later, his enslaver Charles Stewart recaptured Somerset by force and held him on his ship intending to take Somerset to Jamaica to be sold. The English godparents in Somerset’s baptism petitioned for habeus corpus, one of the most important principles in Anglo-Saxon law. Meaning “to have the body” in Latin, the principle requires courts to hear petitions, or “writs,” for release from detention on claims of wrongful arrest. Habeus corpus remains the basis in rule of law of all petitions for release from unjust or wrongful imprisonment.

The abolitionist Grantham Sharpe hired five lawyers to argue for Somerset. After the proceedings, Judge Lord Mansfield ruled in 1772 in favor of Somerset’s liberty.

While not an abolitionist, Lord Mansfield decided the case on rule of law principles. He found that common law (which is law established by custom and tradition or precedent) upheld the principle of liberty from contractual bondage of serfs. Natural law established the basic right of liberty. And in Great Britain no positive law (or law enacted by a legislature) allowed slavery. Lord Mansfield wrote,

[Slavery] is so odious that nothing can be suffered to support it but positive law. . . . I cannot say this case is allowed or approved by the law of England; and therefore the black must be discharged.

Thereafter, most British courts treated slavery as illegal and accordingly the ruling eventually led to the freedom of enslaved persons within Britain (about 14,000, mostly in domestic service). The precedent also propelled that country's abolition movement. Over time, two significant positive laws were achieved: the 1807 Slave Trade Act ending British participation in the slave trade and the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act, which brought about gradual abolition of slavery in the British Empire. In all, 800,000 enslaved persons in the Caribbean and South Africa eventually gained liberty as a result. Also, the Royal Navy was authorized to stop the slave trade; it interdicted 1,600 slave ships and freed 150,000 enslaved persons from 1807 to 1860.

The evolution of law is rarely linear or complete. Indeed, neither of the Acts nor the extension of Anglo-Saxon law to Great Britain’s colonies prevented the British Empire from trampling the rights of many peoples under its domain. The rule of law was often a pretense. More than a century would pass before most of Britain’s colonies achieved independence (see History and, for example, Country Study of Kenya). Yet, in the case of Somerset v. Stewart, advocates of abolition pursued justice and Lord Mansfield acted on basic principles, moving the law towards ensuring greater liberty.

An important example of the evolution and use of rule of law principles was the case of Somerset v. Stewart, which re-enforced principles of liberty established in the law. Above is a depiction of Granville Sharpe interceding with Charles Stewart, a slaver seeking to re-capture James Somerset. Somerset was freed on application for habeus corpus in a decision made by Lord Mansfield. Public Domain.

The Breakdown of Law

In the United States, the periods of slavery and legalized discrimination are among the most flagrant examples within a democratic society of the breakdown of the principles of the rule of law.

The American War for Independence (1775-83) was based on the assertion of natural law rights in the Declaration of Independence and initially fostered efforts in northern states to gradually abolish slavery. Also, slavery’s immediate expansion was limited through the 1787 Northwest Ordinance, which prohibited slavery in territories east of the Appalachians obtained from Britain in the war.

In the United States, the periods of slavery and legalized discrimination are among the most flagrant examples within a democratic society of the breakdown of the principles of the rule of law.

Yet, both Federal and state constitutions and laws upheld the barbaric practice of chattel slavery in southern and mid-Atlantic states as first instituted by colonial governments. After the adoption of the Constitution in 1788, slavery became entrenched and expanded to fifteen states. In 1857, the US Supreme Court, in its most infamous decision, not only upheld the practice of slavery but denied citizenship and all federal protection of rights to any African American, free or enslaved.

Slavery and the Supreme Court’s Dred Scot decision could not co-exist within a national constitutional framework originally based on liberty. As Abraham Lincoln asserted, “A house divided against itself cannot stand. This government cannot long endure half-slave and half-free.”

Through multiracial political struggle and the prosecution of a bloody civil war against a confederacy of rebellious slave states, the US “house” was made fully free in what was called the country’s Second Founding. The nation’s natural law principle — that “all men are created equal”— was more fully incorporated within the US Constitution by enactment of the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments. Positive law now prohibited slavery, protected the rights of citizenship for all natural born persons and guaranteed the vote to Black male citizens.

The Second Founding in the United States furthered rule of law principles, especially by passage of the 14th Amendment. Andrew Cox’s painting “The Passage of the Civil Rights Law” — the 1866 law was the foundation for the Amendment — shows abolitionists Herny Garnet (left) and newspaper editor Horace Greeley as they lobbied for the law. Public Domain.

Even then, however, the judicial system acted against the rule of law. The US Supreme Court repeatedly ruled to deny protection of constitutional rights to African Americans and upheld discriminatory laws (called Jim Crow) that were enacted in the South and in some northern states. These rulings (beginning as early as 1873) allowed the establishment of a system of legalized discrimination and segregation that in the South was imposed through a regime of violence and intimidation.

These laws and Supreme Court rulings turned the guarantee of due process and equal treatment made in the 14th Amendment on its head using the doctrine of “separate but equal.” Other rulings allowed the effective invalidation of the 15th Amendment’s protection for African Americans of the right to vote. Again, the evolution of rule of law principles was neither linear nor complete.

Recommitment to Rule of Law

Yet, it was precisely through a commitment to the principle of the rule of law that Black Americans were able to slowly win back their rights. There were sustained efforts by African Americans and white allies to challenge legal segregation and to argue for upholding constitutional rights in both state and federal courts, most persistently by the NAACP and its Legal Defense Fund.

These efforts resulted in a series of US Supreme Court rulings that re-affirmed the guarantees of the post-Civil War amendments and declared unconstitutional the prior doctrines allowing racial segregation and discrimination. The most famous decision was Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 (see Resources).

[I]t was . . . through a commitment to the principle of the rule of law that Black Americans were able to slowly win back their rights.

Also, the dramatic struggle of the Civil Rights Movement in the post-World War II era convinced a full majority of American society finally to put an end to the systematic denial of equal rights for African Americans and other minorities through sweeping federal civil rights legislation and a constitutional amendment banning poll taxes enacted in the mid-1960s.

These Supreme Court decisions and civil rights laws reflected evolving standards in favor of equal rights that were then affirmed and extended in courts and legislatures to women and other minority groups (such as the right to marriage and job equality for LGBTQ Americans).

Still, equality under the law remains elusive 70 years after Brown v. Board of Education and 60 years after passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and 1965 Voting Rights Act. There are many examples not only for African Americans but also for women and other minorities where rule of law principles have not been fully upheld. This is especially so in individual states following several Supreme Court rulings that reversed the Court's longstanding legal precedents protecting voting rights and reproductive rights. Many Republican-led legislatures have placed new discriminatory restrictions on voting and also adopted draconian abortion bans.

As previously, however, citizens and non-profit legal organizations like the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and the Equal Justice Initiative (see Resources) continue to pursue avenues within the judicial branch of the government to uphold principles of rule of law. In June 2023, for example, the NAACP Legal Defense Fund won a Supreme Court ruling in Allen v. Milligan challenging the state of Alabama’s racial gerrymander that was adopted for the 2022 congressional elections. The Supreme Court declared that the the state’s Black citizens were denied equal representation as guaranteed under Section 2 of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which the Court held was still constitutional. The Court required a redrawing of congressional district maps to allow for a second Black majority district.

The Civil Rights Movement in the post-World War II era in the United States led to Supreme Court decisions and new legislation re-affirming equal rights for African Americans and other minorities. Above is a photo of the largest civil rights protest, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, in 1963, which helped spur passage of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts. Public Domain.

Testing the Institutions

One illustration in the U.S. of the necessary institutions and principles for the exercise of rule of law is the Watergate scandal of the early 1970s. Former president Richard Nixon abused power to cover up illegal activities of his administration and his political campaign aimed at ensuring his reelection. A set of laws and a constitution, a functioning judicial system and law enforcement agencies acted in concert with free media to uphold the rule of law even when it was being abused by the highest official in the land. After lengthy hearings in Congress, the Judiciary Committee of the House of Representatives voted to recommend impeachment of the president. Facing a likely conviction by the Senate, Richard Nixon resigned in 1974 —the first time a president had done so in US history (see also subsections in Accountability and Transparency for a fuller account).

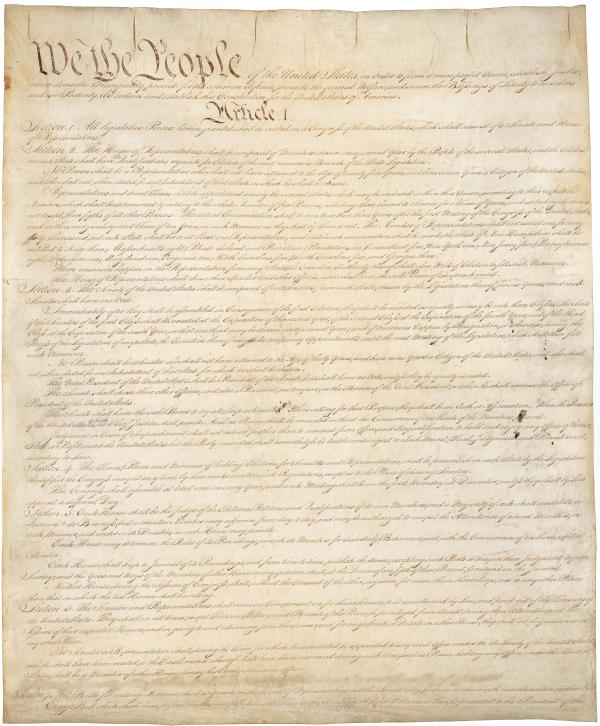

A Constitution or set of comprehensive laws adopted by popular consent is a necessary foundation for the rule of law. Above, the copy of the US Constitution, held at the National Archives in Washington, D.C, the first such basic law to be adopted by popular means in a republic. Public Domain.

The first presidential term of Donald J. Trump, however, showed the limits of these institutions. After having abused his power to aid in his re-election bid, Trump was impeached on two charges by the House of Representatives but acquitted by the Senate in a party-line vote. Following his 2020 election loss, Trump then attempted to overturn the election by various extraconstitutional means and when these failed to prevent the transfer of power he incited a violent mob attack on Congress. Again, largely by party-line voting, the US Senate failed to convict Trump by the necessary two-thirds vote when impeached on the charge of insurrection. (The vote was 57-43 with 7 Republicans voting to convict and 43 to acquit.) A conviction would have barred Trump from seeking public office (see also “US: A Significant Test Case” in Consent of the Governed).

As Trump sought the Republican nomination for the 2024 presidential election, the US Supreme Court overturned a Colorado Supreme Court’s ruling that Donald Trump had committed insurrection and thus must be barred from appearing on the state’s primary ballot under Section 3 of the 14th Amendment (Colorado v. Anderson). As a result, Trump was able to run for president without hindrance to win the Republican nomination.

The criminal justice system also did not provide accountability. In August 2023, the Department of Justice (DOJ) brought a federal indictment of Trump for attempting to overturn the 2020 election. However, legal rulings delayed court proceedings. Most significantly, the six Republican-appointed Supreme Court justices overruled District and Appellate Courts to find in favor of Trump’s legal claim of presidential immunity from prosecution for official acts. The federal case was remanded back to the District Court for further determinations in the case. In the end, the ruling meant Trump did not face trial prior to the 2024 presidential election. Historians and constitutional scholars critiqued both decisions as contrary to the intentions of the framers of the constitution (see Resources).

In the end, voters also did not hold Trump accountable. Donald Trump’s electoral victory to a second non-consecutive term ended the federal prosecution due to a DOJ rule that presidents cannot be tried while in office (a state indictment in Georgia will also likely be dismissed).

A New York state civil court jury did find that Trump had committed sexual assault in the mid-1990s and was liable for defamation for repeatedly claiming the victim was lying about the incident. Another state civil court jury found the Trump Organization liable for business fraud and it was fined $452 million. A Manhattan District Court judge also finalized the conviction of Trump on 34 felony counts for illegally disguising hush money payments to a porn star as business expenses, but without penalty (see Resources for civics lessons deriving from the case). All three verdicts are pending appeals and none of these judgements affected Trump’s election. However, he is the first convicted felon to assume the office of president.

International Rule of Law

The historical examples of evolution of law in Great Britain and the United States are summaries of how essential principles of rule of law developed in complex historical trajectories within two major democracies (see also History). As seen in the Free and Partly Free Country Studies, the rule of law emerged and developed distinctly in all democracies, but with many of the common principles outlined above.

These principles also formed part of an emerging framework of international law based first on the sovereign rights of nations and second on universal principles of human rights.

In the 19th century, many treaties established rules among nations to facilitate trade, transport and communications. Other efforts aimed to end slavery (such as the 1926 Slavery Convention) and to establish rules of war and conflict (such as the Hague Convention of 1907). The carnage of World War I accelerated such efforts with the creation of the League of Nations as well as the International Labour Organization (ILO), which established basic worker rights in international law (see also Freedom of Association).

The ad hoc Nuremberg and Tokyo War Crimes Trials established a precedent for prosecuting individuals who perpetrated crimes against humanity and war crimes on behalf of nation states. Above is a picture of defendants in one of the Nuremberg Trials, the Major Trial of 24, in 1946. Public Domain. National Archives.

The aggression, lawlessness and massive violations of human rights perpetrated by Nazi Germany and other Axis powers in World War II made evident the need for a stronger system of international law. Such a system was established through the United Nations Charter (1945), the ad hoc Nuremberg and Tokyo war crimes trials (1945-48), and the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide by the UN (both adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1948).

As with domestic systems of law, the international system is not always effective. The UN General Assembly and the UN Security Council were given authority to act in cases of aggression and other crimes, but that ability to act has been stymied by conflicting ideologies and interests. This is especially the case with the five major powers given the power to veto any proposed action in the UN Security Council.

As with domestic systems of law, the international system is not always effective. The UN General Assembly and the UN Security Council were given authority to act in cases of aggression and other crimes, but that ability to act has been stymied by conflicting ideologies and interests.

Consequently, while the UN acted in some cases of aggression (as on the Korean peninsula in 1950 and in the first Persian Gulf War in 1991), in many others it did not. Still, in the 1990s and early 2000s, the UN Security Council acted to strengthen the international system of law by setting up special tribunals within the International Court of Justice to try individuals charged with committing genocide and crimes against humanity. It did so in former Yugoslavia, Rwanda and Siera Leone, among others. These tribunals spurred establishment of the International Criminal Court (ICC) in 2002, but its jurisdiction extends only to countries that have signed its Rome Convention (see also History).

Nevertheless, there is a trend towards pursuing violations of international law in both domestic and international fora. The ICC, for example, acted within one year to indict Vladimir Putin and one other person for crimes against humanity and genocide for the mass abduction of Ukrainian children following Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine in 2022 (see also Accountability and Transparency). It also indicted the leaders of Hamas for genocide for their orchestrated attack on Israel killing 1,200 persons indiscriminately and the Prime Minister and Defense Minister of Israel for committing war crimes in the subsequent Israel-Hamas war in the Gaza Strip.

In both domestic and international venues, it is hoped that through institutions of the rule of law the type of lawlessness represented by Stalin’s Soviet Union and Putin’s Russian Federation may be deterred and that violators of basic international standards are brought to justice.

The content on this page was last updated on .