Athenian Democracy and Republican Rome

Elections date back to ancient times, most notably to the Greek city-states and republican Rome. Among Greek city states, Athens in the fifth and fourth centuries BCE had the most historically significant system of direct democracy. All male citizens had the right to participate in the citizens’ assembly (Ecclesia) and vote on public matters (such as taxation and war). They also voted to elect representatives for a variety of offices, from superintendents of the water supply to those leading the city-state in wartime.

Elections in republican Rome, from the sixth to the first centuries BCE, were also carried out in public assemblies, but were segregated in political units by tribes (comita tributa) and by military class (comita centuriata), with voting in the latter assembly weighted by wealth. Weighting the vote was based on the idea that those with more wealth and property had a greater interest in public affairs (an idea adopted initially by some modern democratic systems). Patricians, or the propertied class, were also the ones who could more readily afford to serve in elected office (quaestors, aediles, praetors and consuls).

Elections date back to ancient times, most notably to the Greek city-states and republican Rome.

It was from these offices that individuals were appointed senators. By tradition, the Senate had the greatest power to direct policy, adopt laws and conduct foreign policy, including the power to declare war. Tribunes were elected by plebeians, the common citizens, in a separate assembly. Tribunes acted mostly as interceders, having the power to veto actions of the Senate or magistrates. In certain respects, ancient Rome was more populist than ancient Athens but it was not as democratic. The upper classes retained dominance.

Neither ancient Athens nor Republican Rome were democratic in the modern sense. Ancient Athens and the Roman Republic excluded a majority of their populations from the franchise: women, foreign-born residents and slaves. The Roman Republic, as it expanded, also excluded many over whom it ruled. Even though granted citizenship, most could not afford to attend the assemblies in Rome. Both economies relied heavily on slavery (a fact that enslavers in the American South pointed to as demonstrating democracy's compatibility with slavery in the United States). Still, when compared to other political systems of their times, both Athens and Rome offer more democratic examples and greatly influenced the re-emergence of ideas of self-governance in Europe during the Renaissance and Enlightenment periods.

The British Experience

The signing of the Magna Carta Libertatum (or Great Charter of Liberties) in England in CE 1215 established the basis for the world's oldest and most enduring representative parliament. The Magna Carta inscribed the principle that the monarch was subject to the law and had to consult subjects on matters of taxation and war through a parliament. In the 14th century, the assembly was divided into an upper House of Lords and a lower House of Commons. The former was made up of high clergy and nobles with hereditary rank appointed by the king. The latter comprised representatives elected from counties and boroughs.

The signing of the Magna Carta Libertatum (or Great Charter of Liberties) in England in CE 1215 established the basis for the world's oldest and most enduring representative parliament.

Some counties and boroughs adopted general suffrage, but in 1430 the Parliament established a voting requirement of property generating tax of minimum 40 shillings, a substantial amount at the time. Since Parliament did not change the amount, by the mid-1600s this class of voters grew due to inflation.

By 1642, the House of Commons represented a constituency of smaller property owners capable of raising an army to fight for their “common liberties.” It did so against King Charles I, who had raised an army without parliament’s consent to assert absolutist prerogatives over religion, taxes and war. In the civil wars that followed, Charles I was defeated, captured and executed for high treason for defying parliament. The House of Commons established a Commonwealth and Free State without a monarch.

The English Civil Wars led to a short-lived Commonwealth and Free State. Monarchy was restored, but republican principles were introduced within the British constitutional system. A commemorative stamp of Parliament’s uprising. Shutterstock. Photo Contributor Chris Dorney.

The Commonwealth was short-lived. Led by Oliver Cromwell, it grew militarist and authoritarian. After his death, the monarchy was restored in 1660. But the Commonwealth introduced basic republican principles within the British constitutional system. In 1688, in what was called The Glorious Revolution, the House of Commons again dethroned the monarch, James II, whose adherence to Catholicism had threatened the state religion, Anglicanism. He was replaced by his daughter, Mary II, and her Protestant husband William (the King of Netherlands), whose army was called upon to defeat James II’s forces. The House of Commons then also adopted the English Bill of Rights and other acts to ensure certain rights, introduce fairer representation, and assert powers over succession, taxation and other matters of governance.

Over the next two centuries, the House of Commons became the supreme power over the country’s affairs and the monarchy’s constitutional powers became more symbolic. Further expansions of the electoral franchise, however, waited until the mid–19th century ─ the result of labor and other social and political movements organizing to expand the right to vote. Even then, the franchise was limited to a minority of adult citizens. General suffrage for males and suffrage for single women property holders over the age of 30 was adopted only in 1918 in recognition of the sacrifices of both men and women in World War I. Full suffrage for women was achieved in 1928.

Partial women’s suffrage and full male suffrage was achieved in Britain only in 1918 and full women’s suffrage in 1928. Above, the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) holds a women’s parliament is in Saxton in 1907. Public Domain.

The US Experience

Generally considered the world's oldest democracy, the United States has the longest consecutive history of holding general elections for legislative and executive branches of government. With a constitutional guarantee of republican government in all constituent states, the U.S. also has had continuous elections in each of its states for legislative, executive and, in many states, judicial branches. Most date the continuity of US elections to adoption of the Constitution in 1788. Elections, however, were already an established practice even before independence. They took place for representative assemblies in all the colonies. America’s second president, John Adams, wrote as early as 1761 that “The very ground of our liberties is the freedom of elections.”

America’s second president, John Adams, wrote as early as 1761 that “The very ground of our liberties is the freedom of elections.”

At the country’s founding, the franchise was limited. Under the Constitution, women were not granted the franchise. Enslaved persons and Native Americans were excluded from representation. The US Constitution also did not establish a national right to vote and left the qualifications for voting to be set by individual states. Although one state (Vermont) adopted general suffrage in its constitution, most states adopted property or tax requirements in the belief, similar to Britain at the time, that those with property ownership and tax status should decide on the affairs of the people as a whole. General male suffrage expanded over time and became more common starting in the late 1820s. It was adopted in all states by 1856.

Throughout the period up to the Civil War, however, the franchise was mostly restricted for free Blacks, Native Americans and women — even in non-slave states. Black and white abolitionists engaged in ongoing efforts to overturn restrictions of the franchise to white men in state constitutions in the North. Prior to the Civil War, Black disenfranchisement was reversed in only one state, Rhode Island. These efforts, however, did become the basis for expanding the franchise to include Black men through the 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution following the Civil War (see also "An Enduring Struggle" below).

Throughout the period up to the Civil War, the franchise was mostly restricted for free Blacks, Native Americans and women -- even in non-slave states.

Women’s suffrage was often joined in demands for Black suffrage prior to the Civil War, but it was not included in either the 14th or 15th Amendments. At that time, it was achieved in only two new states (Wyoming and Utah in 1869-70). Women’s suffrage expanded gradually thereafter by state, but it took until 1920, with passage of the 19th Amendment, for full women’s suffrage to be achieved nationally.

Native Americans were recognized as citizens with full eligibility to vote in 1924. The 26th Amendment, adopted in 1971, expanded the franchise to those 18 years and older. Equal suffrage, however, was another matter, as is described in the sections below.

An Enduring Struggle

Since the Declaration of Independence, the most enduring struggle for freedom and equal suffrage in the United States has been that of African Americans. It is through their struggle that the U.S. achieved full democracy.

Since the Declaration of Independence, the most enduring struggle for freedom and equal suffrage in the United States has been that of African Americans. It is through their struggle that the U.S. achieved full democracy.

Race-based chattel slavery, based on black Africans forcibly transported across the ocean and their descendants, was entrenched in the British colonies. At the time of independence, enslaved persons were approximately one-fifth of the population of 4 million. The American Revolution did inspire movements to abolish slavery gradually in northern states and its expansion was barred in Northwest Territories in 1787 (formerly British-held territory west of the Appalachian Mountains). But numerous provisions in the US Constitution, as well as its federal design, ensured the entrenchment of slavery in the South and mid-Atlantic states and allowed its expansion to other territories. The "three-fifths compromise" (counting anyone enslaved as three-fifths of a person for apportioning representation) expanded the political power of slave states. As a result, ten of the first twelve presidents were enslavers, as were a majority of Supreme Court justices and representatives in Congress prior to the Civil War (see The Washington Post article "Who Owned Slaves in Congress" in Resources).

Entrenchment of slavery in the South, as well as discrimination against free Blacks in the North, gave rise to organized Black resistance, which was aided by white and other allies. This took the form of slave revolts in the South, mass escape (including through the organized Underground Railroad), and political movements for abolition, equal citizenship and suffrage that demanded fulfillment of the ideals of equality in the Declaration of Independence.

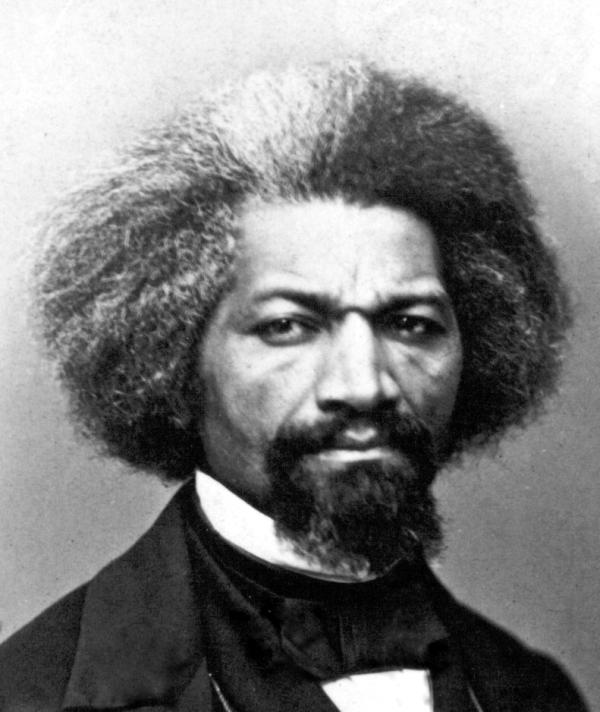

As argued by Frederick Douglass and other abolition leaders, the country’s future rested not just on emancipation but on full enfranchisement of the country’s citizens. Above, a photo of Frederick Douglass in the 1860s. Public Domain.

As noted already above, the movement for voting rights in the North had little success. Organized political opposition to slavery in non-slave states was limited largely due to the US economy’s dependence on slave-state interests. But Black resistance and the multiracial abolition movement of the 1830s and 1840s slowly built the base for political opposition to slavery and support for full suffrage in northern states. Abolitionism gained greater influence through the rise of the Republican Party in the mid-1850s, and then in the victory of Abraham Lincoln, its candidate in the 1860 presidential election.

The subsequent rebellion against the United States and the Civil War broke the hold of slavery. The Union’s victory, with the participation of nearly 200,000 Black volunteers (most of whom were formerly enslaved), brought full emancipation. The Dred Scott decision of 1857, which had denied US citizenship altogether to Black Americans, was formally nullified by the 13th Amendment’s abolishment of slavery and by the 14th Amendment’s affirmation of citizenship for all persons born or naturalized in the United States.

A Brief Victory

In direct response to organized resistance by whites in the South against Black suffrage, Congress and the states enacted the 15th Amendment to the Constitution in 1870.

Abolition leaders argued that the country’s future rested not just on emancipation and equal citizenship but also on full enfranchisement of the country’s Black citizens, who represented more than ten percent of the population and a full majority in some Southern states.

In direct response to organized resistance by whites in the South against Black suffrage, Congress and the states enacted the 15th Amendment to the Constitution in 1870. It guaranteed that “the right of citizens . . . to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude."

For a brief period during Reconstruction, the 15th Amendment, backed by federal military authority, achieved equal suffrage for Black men. A large majority voted in elections and many were elected to local offices, state legislatures and Congress. There were working Black-white coalitions in the Republican Party and fusion coalitions with those in the Democratic Party who accepted the outcome of the Civil War.

A Return to Majority Tyranny

Yet, African Americans quickly faced a new form of white oppression. A reactionary and racist Democratic Party took hold in the former Confederate states of the South that re-entered the Union. Violence (through groups like the Ku Klux Klan) was used systematically to limit Black empowerment, repress civil rights and the vote, and restrict Black property ownership. In the “Compromise of 1877,” Republican Rutherford B. Hayes gained the presidency in exchange for agreeing to withdraw federal troops from former Confederate states and thus end Reconstruction.

The 15th Amendment brought about the election of the First Black Senator and Representatives to the US Congress. The Capitol Men in 1872 (left to right): Senator Hiram Revels (MS), Representatives Benjamin Turner (AL), Robert DeLarge (SC), Josiah Walls (FL), Jefferson Long (GA), Joseph Rainey (SC) and Robert B. Elliot (SC). Creative Commons License. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

The 1877 “compromise” allowed the Democratic Party to fully re-establish its dominance in southern state governments. Discriminatory laws, poll taxes and other obstacles to voting were adopted that applied only to Black citizens. By the mid-1890s, African Americans had been systematically disenfranchised soon after being freed from bondage and supposedly guaranteed the right to vote as full citizens. A series of Supreme Court decisions (culminating in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896) upheld discriminatory Jim Crow laws.

The multi-racial political movement for equality that gained strength during the Civil War and after the Union’s victory dissipated. A regime of majority tyranny based on violent repression was again entrenched in a large region of the United States, while discrimination of Black Americans and other minorities also became prevalent in the rest of the country.

The Struggle for Equality

Over the next 75 years, African Americans, joined by other minorities and white allies, organized resistance to systematic disenfranchisement and discrimination using non-violent methods.

In the 1940s, political pressure organized by A. Philip Randolph through the March on Washington Movement succeeded in obtaining presidential orders, first by President Roosevelt in 1941 and then by President Truman in 1948, that banned segregation in defense industries, the federal workforce and the US armed forces. Randolph, as with other Black leaders, pointed directly to the gross hypocrisy of the United States fighting for freedom abroad in World War II while denying it to people of color at home.

In the 1940s and 1950s, a concerted effort by the NAACP and its Legal Defense Fund led to a series of Supreme Court decisions, culminating in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, that reversed segregationist doctrine and provided substantive protection of the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of equal rights to Black citizens.

The Selma to Montgomery March propelled passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965. Pictured above (clockwise from top left): Alabama police attack John Lewis leading the first attempt ("Bloody Sunday"); a solidarity march in Harlem, NYC; Dr. Martin Luther King and others leading the successful march weeks later; participants in the Selma to Montgomery march. Public Domain.

The Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s then brought about the most significant changes: abolishment of the poll tax in 1962 (through the 24th Amendment) and passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the 1965 Voting Rights Act (VRA) and other civil rights legislation.

Political support for civil rights and equal voting rights among enfranchised whites (the large majority) had increased only slowly over the course of the 20th century. The mass protest and resistance movement for equal rights brought about majority support for such measures, indicated by a landslide victory for President Lyndon Johnson’s re-election on a platform including civil and voting rights.

A Real Democracy

It is with passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) that many political scientists consider the United States to have become a real or genuine democracy with universal suffrage (see articles by Larry Diamond and Nikole Hannah-Jones in Resources). The VRA, by instituting federal oversight and intervention, brought an end to the systematic denial of voting rights by individual states and led to improvements in voter registration, participation in elections and political representation for Black Americans and other minorities, including Native Americans and persons with disabilities.

It is with passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) that many political scientists consider the United States to have become a real or genuine democracy with universal suffrage.

By the 2008 and 2012 national elections, the percentage of voter registration and voter turnout for Blacks had returned to Reconstruction-era levels. Black voter turnout of eligible voters exceeded that of white Americans nationally for the first time in 2008 (at 62 percent). Over decades, African Americans, as well as other minorities, achieved steadily increasing representation in local offices, state legislatures, the House of Representatives and the Senate. In 2008, Barack Obama, representing a multiracial coalition, was the first African American elected president of the United States by a national vote of 53 to 46 percent. He was re-elected in 2012 by a slightly smaller margin.

Elusive Equality

Full voting equality, however, remains elusive.

Since the United States Constitution has no affirmative right to vote and no national law establishes such a right, states continue to have wide powers to set the rules and regulations of elections. While most states do have an affirmative right to vote in their own constitutions, that right is frequently violated in state legislation and practice. Starting after the 2008 election, many states enacted new voting restrictions and qualifications.

These laws included requirements for non-universal forms of identification to vote, the purging of eligible voters from the voting rolls, limiting more accessible means of registration and voting, partisan redistricting and restricting voting rights of formerly incarcerated persons. Such laws disproportionately impacted voter registration and participation of the poor and elderly generally, but especially Blacks and other minorities.

Full voting equality, however, remains elusive. . . . Starting after the 2008 election, new voting restrictions and qualifications were enacted in many state laws, largely in response to the increasing participation of Blacks and other minorities in elections.

These restrictions and qualifications increased as a result of several Supreme Court decisions. In 2013, in Shelby v. Holder, the Court ruled that Section V of the Voting Rights Act was unconstitutional. Section V had required that changes to election laws by a state with a prior history of voting discrimination had to be approved, or pre-cleared, by the Department of Justice. After preclearance was no longer required, the affected states, mostly the former Confederacy but not only, passed laws making voter registration and voting more difficult.

A Supreme Court decision in 2018 (Brnovich v. DNC) overturned a key element of Section 2 of the VRA, which barred discrimination more generally in state and local election laws. Other Supreme Court decisions upheld the purging of voting rolls, partisan gerrymandering and racial gerrymandering. Such gerrymandering after the 2020 Census significantly limited Black and other minority representation in the 2022 elections and gave particular advantage to the Republican Party in at least ten states.

An unexpected decision in 2023 (Milligan v. Alabama) upheld the underlying framework of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act for equal representation and reversed a racial gerrymander in Alabama. The decision resulted in an additional majority minority district in that state and Louisiana.

The US Supreme Court’s decisions have allowed states to make voting more difficult in many states. In Georgia, there are often fewer polling places, making voting lines, often hours long, a common occurrence. Shutterstock. Photo by Michael Scott Milner.

Historical Role Reversal

The voting rights issue has partisan expression with the historical role of the two political parties reversed. Since the 1960s, the Democratic Party has acted to expand voting rights and minority representation at the local, state and national levels, while the Republican Party has acted increasingly over time to restrict those rights and limit minority representation. According to the Brennan Center for Justice, twenty-six state legislatures with Republican majorities adopted more restrictive laws for voting from 2010 to 2020. During that period, all states with Democratic majorities have expanded voting rights and opportunities for all citizens in accordance with the original Voting Rights Act and other federal laws aimed at encouraging exercise of the right to vote (see Resources).

In 2021-22, forty-two laws with new limits on voter registration and voting methods were adopted in twenty-one Republican-dominated states. Most were in force in the 2022 national election. Additional restrictions have been adopted since then. In all cases, these restrictions have been shown to limit participation of older, poorer, minority and disabled voters in elections. This can be seen in lower voting rates among these groups (see Washington Post article "Do Voter ID Laws Suppress Minority Voting?" in Resources).

Universal and Equal Suffrage

As the lengthy discussion of the U.S. experience demonstrates, a fully participatory democratic political system that includes all adult citizens isn’t achieved quickly or easily.

As the lengthy discussion of the U.S. experience demonstrates, a fully participatory democratic political system that includes all adult citizens isn’t achieved quickly or easily. Often, greater representation and participation of citizens in a democracy emerges from long and difficult struggles for freedom, democratic rights and full suffrage.

By contrast with the United States and Great Britain, the French Revolution in 1789 established political participation as a civil right. General male suffrage was included in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen and the subsequent 1793 Constitution. The French Revolution, however, shows similarly how difficult it is to establish full democracy. The Revolution descended into a period known as the “Reign of Terror” in 1793-94. After the National Convention, a general parliament, ended the terror, a new constitution was adopted in 1795 that again limited suffrage and established a stronger executive. Political instability and foreign attack led to the imposition of a military dictatorship under the rule of Napoleon Bonaparte. The monarchy was restored in 1815 after Napoleon’s final military defeat by European powers.

Across the globe, women's suffrage lagged general male suffrage, but it also advanced progressively over time. New Zealand was the first country to grant universal suffrage including women in 1893.

Yet, over the 19th century, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen became a basis for future French republics. General manhood suffrage was restored in France’s Second Republic in 1848. The Declaration was also a source of democratic inspiration across Europe and elsewhere. Although revolutions in 1848 were mostly suppressed, more representative political systems ultimately emerged from popular social and political movements. By the turn of the century, general male suffrage was adopted by a number of European countries.

Across the globe, women's suffrage lagged general male suffrage, but it also advanced progressively over time. New Zealand was the first country to grant universal suffrage including women in 1893; Finland was the first European country to do so in 1906. As the first democracy in the Muslim world, Azerbaijan adopted universal suffrage including women in 1918 (see Country Study in this section). As noted above, the United States and the United Kingdom instituted full women's suffrage in 1920 and 1928, respectively.

France, although being the first to adopt general male suffrage, achieved women's suffrage only after the country's liberation from Nazi occupation in 1944 (see Country Study in Constitutional Limits). In many other countries, general suffrage took longer to adopt than in the U.S. and European countries. Venezuela, for example, did not lift property, literacy, and other restrictions on voting until 1946 (see Country Study in this section).

The New Normal

Free, fair and regular elections were made the international norm following World War II through adoption of Article 21 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Free, fair and regular elections were made the international norm following World War II through adoption of Article 21 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (see also Essential Principles). Indeed, the UDHR’s adoption in 1948 was one of the bases for the movement to integrate the US armed forces the same year and later to ensure civil rights and expand voting rights in the United States to Black Americans (see above). Article 21’s broad principles were the standard adopted in the independent nations that emerged during the period of decolonization. Even most dictatorships adopted universal suffrage, although not principles of free and fair elections.

From the mid-1970s to the mid-2000s, democracies took hold in countries of southern and Eastern Europe, Africa, Asia and Latin America. Free, fair and regular elections with universal suffrage became the norm for a majority of countries and a majority of the world’s population. There are 110 electoral democracies listed in the 2023 Freedom in the World survey. The number has increased significantly from the first survey in 1973, when only 44 countries qualified. Of the 110 electoral democracies, 84 are considered free and 26 partly free. (In the latter countries, there are competitive elections, but often with unfair conditions favoring the ruling party.)

The Recent Trend

While the larger political movement since the end of World War II has been towards democracy, recent trends have seen a decline in political rights and civil liberties.

Freedom House’s 2024 survey shows overall declines in freedom rankings worldwide for the eighteenth straight year. In most of those years, there has been a rise in authoritarian practices in countries as diverse as Hungary, Turkey and Venezuela. As well, there has been a hardening of authoritarian regimes in countries such as Belarus and Russia. While all of these countries have regular national elections, they are neither free nor fair. To varying degrees, the governments restrict the possibility for electoral competition or prevent it outright; they manipulate the electoral process and laws to the ruling party’s advantage; they dominate or control the media; they restrict or deny fully rights of expression, association, assembly and due process; or, when none of these methods work, they control the electoral administration and simply steal elections and assert a false vote.

While the larger political movement since the end of World War II has been towards democracy, recent trends have seen a decline in political rights and civil liberties.

The Freedom House survey has also seen a weakening of rights and liberties within democracies, including in the conduct of elections. This is the case even in established democracies of Europe and the Western Hemisphere. As well, anti-liberal, chauvinist and neo-fascist political parties and candidates have gained greater political representation in many countries in Europe and elsewhere. When gaining full control of the government, such parties set out to undermine democratic institutions and manipulate the electoral process to maintain power (for example, in Poland until elections in 2023 and Hungary).

In the United States, one of two major political parties has adopted anti-liberal and chauvinist policies to restrict immigration, electoral competition and basic freedoms (see above). That party now regained dominant national power by winning the 2024 presidential and Congressional elections. Its leader, as the prior president, organized a “multi-part conspiracy to overturn the 2020 election” to keep power previously. It remains to be seen the degree to which that party and its leader, now elected by a narrow margin to a second non-consecutive term, will undermine democratic norms and the Constitution and to affect the fairness of future elections.

Still, democracy has shown some resilience through free and fair elections. Non-chauvinist parties and parties and candidates adhering to democracy’s basic principles in their platforms have won majorities in recent elections in numerous regions and countries, including Botswana, Brazil, Estonia, France, Guatemala, Malaysia, and Poland (see Current Issues subsections in each of the Country Studies).

There also continue to be many countries where people bravely stand up against repression and dictatorship to make their demands for democracy heard. They do so at risk of both life and liberty. This has been the case in recent years in Burma, Hong Kong and China, Iran and Sudan, among others. Even where dictators hold elections under unfree and unfair conditions, citizens still try to use them to achieve democratic change, as noted above in Belarus in 2020 and Venezuela in 2024.

Freedom House’s 2024 survey recorded worldwide declines for the 18th straight year, but in many countries people brave repression to demand democracy. Above, a half-million people protested the stealing of elections in Minsk, Belarus in 2020. Creative Commons License. Photo by Maksim Shikunets.

The content on this page was last updated on .