A Brief Survey of Major Religions

From the outset of civilization, governance and religion were intertwined, with an official religion used as a justification for both ruling authority and territorial expansion. Ancient Egyptians, Hittites, Greeks, Persians and Romans, among others, invoked various sets of polytheistic gods to bolster loyalty to the ruler and support for a ruler’s wars of conquest.

From the outset of civilization, governance and religion were intertwined, with an official religion used as a justification for both ruling authority and territorial expansion.

The major religions practiced today have been central elements of empires and autocratic systems. Hinduism, a polytheistic religion, emerged in the Indian subcontinent in the second millennium BCE, and was an integral belief system for dynasties and kingdoms throughout Southwest and Southeast Asia. Buddhism, a set of ethical precepts and practices to achieve spiritual enlightenment, was founded in northern India in the sixth century BCE based on the teachings of Buddha. It, too, was adopted by monarchies in the region.

Starting from the 2nd century BCE, Chinese emperors oversaw the fusion of a complex of religions and practices (Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism and folk religion). These were adopted to justify imperial rule (notably Confucianism and neo-Confucianism). Although its constitution guaranteed religious freedom, the People’s Republic of China has suppressed religion (see below). Still, many people continue observance of former state-supported religions or Christianity, introduced by Western missionaries in the 18th century.

Symbols of six of the major religions of the world, clockwise from the top: Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, Taoism and Christianity.

Today, Hinduism, Buddhism and Chinese traditional religion are no longer state religions except in a few cases. They constitute the world's third, fourth and fifth largest faiths, according to the Pew Research Center (see Resources). Existing within both democratic and autocratic systems, they have estimated followings of 1.2 billion, 500 million and 350 million persons, respectively.

Christianity, with an estimated 2.4 billion adherents (31 percent of world's population), and Islam, with 1.9 billion followers (25 percent), are the world’s largest religions. Both are monotheistic, emerging out of the Abrahamic or Jewish tradition (see below). Each expanded significantly through adoption as an official state religion and by conquest.

Christianity’s adoption by Emperor Constantine in the 4th century CE led to its later official adoption in both Western and Eastern Roman Empires, greatly expanding the faith. Islam was spread by conquest in the 7th and 8th centuries CE by the armies of the Prophet Muhammad and succeeding caliphs. It expanded further by conversion and conquest to other areas of Asia, Africa and Europe. The Ottoman Empire became the center for Sunni Islam from the 15th century to the early 20th century. Christianity and Islam both had schisms resulting in internecine wars, while Christian- and Islamic-centered empires engaged in centuries of intermittent combat between themselves in the Near East and Europe (see also below).

Roman Emperor Constantine converted to Christianity and granted its tolerance in 309 CE. Above, a marble portrait of Constantine’s head in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Creative Commons. Bequest of Mary Clark Thompson, 1923.

Judaism, the world's oldest monotheistic faith, originated in the 1st to 2nd millennia BCE. Jews formed two states in the Near East, one with Jerusalem as the capital. It was the center of religious and political life for Jews until 70 CE, when the Roman army destroyed the Second Temple. For millennia, Jews lived mostly in diaspora, both in the region and in Europe and Africa, often subjected to persecution and expulsion by governments (see below).

In the late 1800s, a movement arose urging migration back to Judaism’s homeland, then known as Palestine, for re-establishment of a Jewish state. In the wake of Nazi Germany's murder of 6 million Jews in the Holocaust and the desperate migration of many surviving Jews to Palestine, the United Nations mandated creation of Jewish and Arab states side by side in the territory. The state of Israel was formed in 1948. The Arab League rejected the partition, leaving a state for Arab Palestinians unresolved to this day (see Israel Country Study). Israel’s population is estimated at 9.5 million, with around 75 percent being Jewish. More than eight million Jews still live in diaspora (with from 5.5 to 6.8 million residing in the United States).

Tolerance and Intolerance

As noted, states and empires adopted official religions throughout most of history. Their rulers were often regarded as both the religion’s spiritual or titular leader and as having divine power or mandate to govern. Those adhering to other faiths, including folk or home-grown religions and smaller branches of major religions, were often persecuted or discriminated against based on taxation, regulation or other obligation to the state.

[R]ulers were often regarded as both the religion’s spiritual or titular leader and as having divine power or mandate to govern. Those adhering to other faiths, including folk or home-grown religions and smaller branches of major religions, were often persecuted or discriminated against.

Even so, there are many historical examples of state tolerance of plural religions within the same territory. Cyrus the Great granted religious freedom throughout the Achaemenid Empire (this freed Jews in captivity in Babylon). The Buddhist Maurya Empire on the Indian subcontinent established religious freedom through the Edicts of Ashoka, a ruler in 3rd century BCE. The Roman Empire had varying policies, some tolerant and some intolerant (Judaism was allowed, Christianity persecuted until Emperor Constantine in the early 4th century CE). The Pact of Umar (637 CE) established dhimmi status within the Islamic Caliphates. In exchange for tax and other obligations, non-Muslim “believers of the book” (Jews and Christians) were allowed to practice their religions. Genghis Khan granted religious freedom to everyone in the Mongol Empire. As noted, Chinese dynasties over time synthesized several religions (Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism and Chinese traditional, or folk, religion).

When Western Roman Emperor Constantine I adopted Christianity in 309 CE, he and his eastern counterpart Licinius granted formal tolerance to Christianity (Galerius granted it legal status in 311 CE). Tolerance turned to intolerance quickly.

Theodosius I, the eastern Roman Emperor, and his western counterpart Gratian established Nicene Christianity as the whole empire’s official religion in 380 CE. Their Edict of Thesalonica outlawed other religions, including Arianism (which considered Christ not to be divine in life) and Judaism. There evolved major differences between the Western (or Latin) Church and the four Eastern (or Greek) Churches. This resulted ultimately in the Great Schism of 1054 and the divergence of Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy.

Crusades, Expulsions and Intolerance

Many European monarchies adopted laws and practices against Jews despite their being a small religious minority. King Edward I of England, shown in an icon above, expelled Jews entirely from national boundaries in 1290. Public Domain.

Prior to the Great Schism, the Holy See in Rome and its bishop, the pope, had asserted the ultimate authority for the entire Church, which grew increasingly intolerant. The Vatican emerged as a supranational entity (and is today still recognized as its own state). It had power to exercise spiritual as well as temporal authority over the Western Roman Empire, in lands further north and in the British Isles. Beginning in 1095 CE, the Pope launched many Crusades to reverse the Islamic conquests with the principal aim of retaking Jerusalem and the Levant for Christendom. The effort ultimately failed and led to enduring conflict that included the Ottoman Empire (see below).

Monarchs or rulers who accepted western Christianity (Catholicism) recognized the pope's religious supremacy, thereby granting divine authority to secular rule. This included the Holy Roman Empire (see also Country Studies of France and Germany). It served to expand western Christianity as far as the Baltic region and Belarus (see also Country Study of Estonia).

The Roman Catholic Church reserved the power to excommunicate rulers and combat heresy through institutions like the Inquisition in Spain and The Sacred Congregation of the Index. The latter was responsible for banning books such as Copernicus’s and Galileo’s affirmations of heliocentrism, thus hindering scientific advancement (see History in Freedom of Expression).

The Roman Catholic Church reserved the power to excommunicate rulers and combat heresy through institutions like the Inquisition in Spain and The Sacred Congregation of the Index.

In accord with the Church, most European monarchies adopted laws and practices against Jews and promoted conspiracies of inordinate power held by this small religious minority. Such conspiracy theories gave rise to enduring anti-Semitism. King Edward I of England was the first to expel Jews entirely, in 1290. During the Reconquista, the Kingdoms of Castille and Aragon expelled both Moors and Jews in 1492 in the Alhambra Decree. During that broad period, Jews found haven in several countries as well as in the Ottoman Empire. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth afforded full religious freedom and sanctuary to Jews through the Warsaw Confederation of 1583.

The Reformation and Wars of Religion

The modern conception of freedom of religion begins with the Reformation, a schism within Christianity between Roman Catholicism and Protestantism.

The modern conception of freedom of religion begins with the Reformation, a schism within Christianity between Roman Catholicism and Protestantism.

Earlier protests of papal authority were raised, but one seen as launching the Reformation was that by Martin Luther. He sent his Ninety-Five Theses to the Archbishop Mainz in 1517 and posted them at doors of Wittenburg churches. The theses challenged the authority of the Pope and lower Church authorities especially for selling of indulgences (absolution from punishment for forgiven sin). Priests and bishops, as well as the Pope, used the practice to raise money for Church projects and themselves.

Pope Pius V ultimately banned the purchase of absolutions fifty years later, but Luther’s protest tapped popular dissent with the absolutism of papal authority. The Ninety-Five Theses gave rise to Lutheranism and other sects and churches that rejected Roman Catholicism and formed congregations associated more directly with national, regional or local communities.

Although not the first to challenge Church authority, Martin Luther was seen as launching the Reformation with his Ninety-Five Theses, also called the Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences. Above, a portrait of Luther from 1528 by Lucas Cranach the Elder. Public domain.

The schism led to internal repression, civil conflicts and wars between states. Catholics refusing the new religion in Protestant states were seen as agents of the Pope or of foreign Catholic rulers. Catholic state rulers in turn viewed Protestant minorities as disloyal heretics. Protestant governments also faced challenges from more radical sects and movements.

Catholic and Protestant states vied for temporal and spiritual supremacy at the same time as they justified empires in the New World based on religion. In doing so, they engaged in a series of bloody religious wars in the 16th and 17th centuries that devastated much of Europe. During the Thirty Years' War alone, from 1618 to 1648, as much as a third of the population in German principalities perished. The Austrian Empire, Russia and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth were also engaged in religious and territorial wars with the Ottoman Empire, whose advance in Europe was stopped at the 1683 Battle of Vienna.

The Wars of Religion ended through treaties and decrees that lay a foundation for religious freedom between and within states. The Union of Utrecht in 1579 established a united Protestant Netherlands independent from Catholic Spain. In France, Henry IV’s Edict of Nantes in 1598 granted civil and religious rights to Protestants (called Huguenots), although these were rescinded by his son, Louis XIII. Most importantly, the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648 ending the Thirty Years' War re-enforced the principle of cuius regio, eius religio (whose region, his religion). Under the principle, any state had the right to establish its own religion, removing religion as a casus belli (cause for war).

Catholic and Protestant states vied for temporal and spiritual supremacy at the same time as they justified empires in the New World based on religion. In doing so, they engaged in a series of bloody religious wars in the 16th and 17th centuries that devastated much of Europe.

In England, Henry VIII declared himself head of a national Church of England in 1534 and separated it from the Vatican due to the Pope’s refusal to recognize the monarch’s divorce. All subjects were required to pledge obedience and faith to the Church of England, with the monarch serving as its leader. (This became the basis for Episcopal religions in the British empire.)

More than a century of intermittent clashes over religion in the British Isles led to adoption of the 1699 Act of Toleration, which granted religious freedom to “Nonconformists” (radical Protestants who rejected the Church of England). The Act, however, excluded protection from Catholics and Dissenters (Protestants who would not pledge allegiance to the state). Catholics continued to be discriminated against until The Papists Act of 1778, which granted some civil rights, and the Roman Catholic Relief Act of 1829, which granted nearly full rights, including to vote.

The Enlightenment and Rise of US Democracy

It is in the last two-and-a-half centuries that states have more fully practiced freedom of religion. Religious freedom has had three basic principles: (1) there should be no state-imposed beliefs or observances on citizens or elected officers; (2) all individuals have the right to practice the religion of their choice or to practice no religion without discrimination; and (3) all religions have freedom to practice and administer themselves without state interference (see also Essential Principles).

[T]he fuller understanding of religious freedom was a product of the Enlightenment, a period of scientific and philosophical discovery in Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries in which scholars placed new emphasis on human reason — not divine authority — as the basis of knowledge.

The emergence of religious freedom as an individual right was due partly to the rise of multiple churches within Protestantism (Episcopal, Lutheran, Anabaptist, Methodist, Presbyterian, among others). Mostly, the fuller understanding of religious freedom was a product of the Enlightenment, a period of scientific and philosophical discovery in Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries in which scholars placed new emphasis on human reason — not divine authority — as the basis of knowledge.

Just as theologians of the Reformation had challenged religious authority to seek what they believed was a truer spiritual understanding of and relationship with God, Enlightenment thinkers challenged the religiously approved knowledge of their time to uncover fundamental laws of nature and the universe. The Enlightenment's scientific method gave rise to Deism, a non-denominational monotheistic belief that rejected ideas of supernatural intervention. It instead imagined God as the rational architect of the universe.

Deism was espoused by many Founders of the United States, including Thomas Jefferson, who believed that institutional forms of religion were a matter of personal opinion and conscience and that state-imposed religion was coercive and corrupting. In a letter, he wrote, “I have sworn upon the altar of god eternal hostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man.” Each person, he wrote, was accountable only to "his God."

Thomas Jefferson, witnessing the repression of Quakers, Anabaptists and other minorities in states that had adopted an official religion, including his own Virginia, saw a fundamental contradiction between the political liberties sought from Britain and the religious intolerance in new states.

This was not only a matter of belief but also a necessity for creation of a new independent state. The American colonies were refuges for dissenters of established religions — whether Protestant sects that arose in Europe or Catholics and Dissenters fleeing persecution from Britain. Yet, they often encountered intolerance again as colonies adopted their own official religions. Among the few that did not was Pennsylvania. Its founder William Penn, a Quaker, established freedom of religion in his Framework of Government.

Thomas Jefferson, witnessing the repression of Quakers, Anabaptists and other minorities in states that had adopted an official religion, including his own Virginia, saw a fundamental contradiction between the political liberties sought from Britain and the religious intolerance in new states. He drafted the Statute for Establishing Religious Freedom with the three principles outlined above put in law. The bill passed the Virginia Legislature in 1786.

James Madison drafted similar principles of religious freedom even more concisely in the Constitution's First Amendment, ratified as part of the Bill of Rights in 1791: "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof. . . ."

Separation of church and state guaranteed everyone the right to worship as his or her conscience dictated. Over time, the US constitutional principle of freedom of conscience, even if often violated in practice (see US Country Study), became common in the laws and practices of all liberal democracies. Each country found that formally denying rights based on religion contradicted common rights of citizenship (such as the right to vote). Even those countries that retained state religions (like England) passed laws providing rights of freedom to worship and equal treatment in basic rights.

Twentieth-Century Dictatorship

[R]eligious persecution has a long history. It continues in many parts of the world. Where freedom of religion is not respected, typically the government is a form of dictatorship.

As seen above, religious persecution has a long history. It continues in many parts of the world. Where freedom of religion is not respected, typically the government is a form of dictatorship. In the 20th century, especially during totalitarianism’s rise, the use of religion for political purposes took new forms.

Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini of Italy was antireligious, but to consolidate power he obtained an agreement from the Roman Catholic Church in 1929 that granted moral legitimacy to his government in return for concessions to the Vatican, including making Catholicism the state's official religion.

Nazi Germany adopted a racist ideology of Aryan supremacy that superseded religion. Christian denominations had to choose between persecution or subservience to the Nazi state and ideology. Some clergy and lay activists resisted Nazism (and were sent to concentration camps as a result). Many religious officials, whether out of sympathy for or fear of the Nazi state, did little to resist. Based on racial ideology, Nazi Germany subjected its minority Jewish population and that of conquered states to persecution, imprisonment and ultimately Hitler’s “Final Solution” of extinction. Six million Jews were killed by Nazi Germany in the Holocaust, three million of them from Poland.

Communism at first did not formally co-opt religious institutions. Instead, it attempted to rid people of religious beliefs and impose an atheist and materialist ideology. . . .

Communism at first did not formally co-opt religious institutions. Instead, it attempted to rid people of religious beliefs and impose an atheist and materialist ideology. Following the Russian Revolution in 1917, the Bolshevik regime destroyed churches, arrested or killed many priests and banned observance of many faiths.

When it suited its purposes, however, the regime recognized religious institutions. After Nazi Germany broke its pact with the Soviet Union and invaded in 1941, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin looked to the Russian Orthodox Church to rally support for what was called the Great Patriotic War. Stalin allowed re-opening of churches and restored the patriarchate, or church leadership, so long as it accepted the communist regime's political authority. Religious officials were handpicked by the state and usually served as police agents or informers.

Muslim and Jewish organizations submitted to similar control in order to maintain religious practice for believers, but discrimination was constant for both groups. Soviet Jews attempting to emigrate to Israel from the 1960s to 1980s were refused exit visas (they were called “refuseniks”). Independent churches were also outlawed and repressed, a practice continued by the Russian Federation.

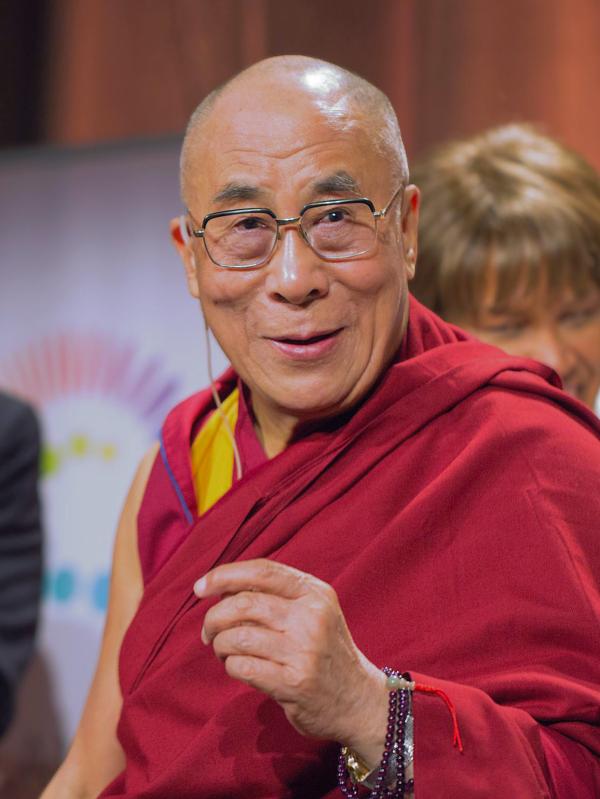

Dictatorships in the 20th century harshly repressed religious belief. Among the most notable instances is the cultural genocide of Tibetan Buddhists by the People’s Republic of China. Tibet's spiritual leader the Dalai Lama, above, was forced into exile after China’s invasion of Tibet in 1959. Creative Commons. Photo by Christopher Michel.

Some religious institutions functioned in Soviet-controlled Central and Eastern Europe but usually as state instruments or under strict control. Only the Roman Catholic Church in Poland retained independence and allowed an officially unimpeded relationship to the Vatican. As Poland’s only independent institution, the Church served as an inspiration for the trade union Solidarity (see Poland Country Study). Cuba’s communist government after 1959 also allowed the Catholic Church to continue functioning, but under restrictions.

In the People’s Republic of China, places of worship were destroyed in state and police-directed anti-religion campaigns. The 1954 Constitution granted religious freedom, but the state imposed tight controls modeled on the USSR over just five allowed religious organizations. Independent religious institutions (such as the spiritual group Falun Gong and the Roman Catholic Church) are repressed or operate under state impediments. Since 1959, China also brutally suppressed Buddhist practice in Tibet, driving the Dalai Lama, Tibet’s spiritual leader, into exile. Recently, the government has acted against Muslim practice in Uyghuristan, a western region. In both cases, the United States and other governments determined that China is committing ethnic and cultural genocide (see Country Study).

A New World Order

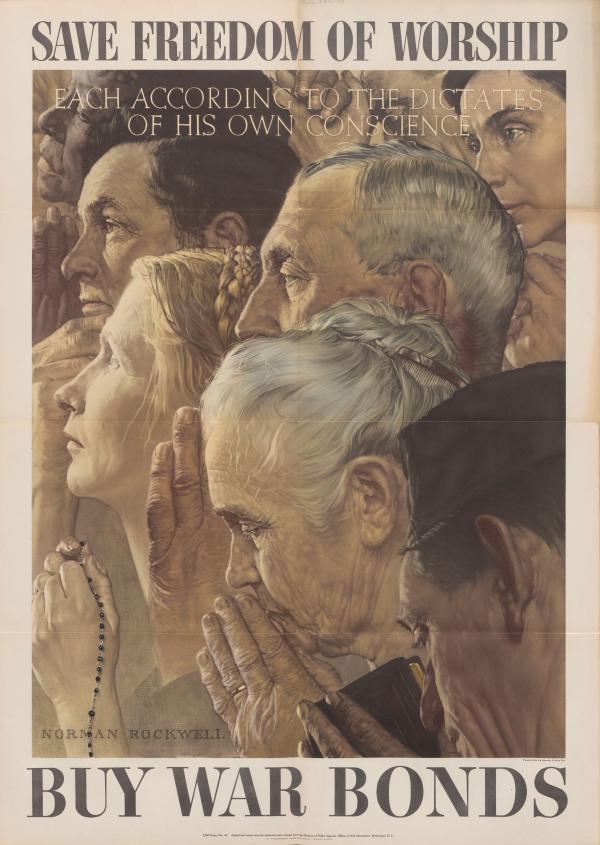

In the face of the Axis Powers’ challenge to world freedom, President Franklin Roosevelt gave a powerful State of the Union Speech in 1941 where he listed four basic freedoms he believed must be protected as the foundation for a new post-war international system. These were: freedom from fear, freedom from want, freedom of speech and “freedom of every person to worship God in his own way — everywhere in the world.”

President Roosevelt outlined Four Freedoms on which to base a new post-war international order. One was “freedom of every person to worship God in his own way—everywhere in the world,” Above, citizens are urged to buy war bonds on this basis in a poster by Norman Rockwell. Public Domain.

This last freedom referred especially to Nazi Germany’s relentless persecution of Jews that had made clear the totalitarian danger of targeting a minority group for their religion. Roosevelt’s “Four Freedoms Speech” was a foundation for the Atlantic Charter signed later that year by the US President and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. The Atlantic Charter further laid out principles for a post-war international order to ensure future peace and was the basis for establishing the United Nations.

Following her husband’s death, Eleanor Roosevelt, a human and civil rights crusader in her own right, was named by President Truman to lead the US delegation to the UN Commission on Human Rights. As chairwoman of the Commission, she ensured that “the four freedoms,” including the principle of freedom of religion and conscience, was embedded in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). Article 18 states:

Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.

The inclusion of freedom of religion in the UDHR (1948) — and subsequently in the European Convention on Human Rights (1953) and the UN Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966) — did not end repression of religious freedom (as seen above and below). But, together with the gradual spread of decolonization and democracy, the UDHR, ECHR and UN Covenant established an international standard for freedom of religion and tolerance of different faiths — as well as of non-belief — within nation states (see below).

Current Dictatorship and Non-State Actors

Of course, there are many instances of religious repression and intolerance by dictatorships around the world. Today, these include communist Vietnam’s repression of non-registered religions (see Country Study in this section); the Taliban’s imposition of repressive Islamic practices after regaining power in Afghanistan; Saudi Arabia’s stifling Islamic orthodoxy overseen by its religious establishment; and Iran’s equally stifling theocratic regime.

Dictatorial states that join religion with state governance like Iran and Saudi Arabia (as well as Sudan prior to 2019 and Afghanistan after 2021) not only impose repressive religious interpretations within their own countries but also export them abroad. The export of extremist interpretations of both Sunni and Shi’a Islam fueled the rise of extremist groups who recruited cadres of terrorists to wage jihad — or war — on governments and civilian populations.

Dictatorial states that join religion with state governance like Iran and Saudi Arabia . . . not only impose repressive religious interpretations within their own countries but also export them abroad.

Often this extremist violence has been directed in terrorist attacks on the United States, Europe and Israel, which are blamed for subjugating the Muslim world to modernity and liberalism. Generally, extremist non-state groups are unsuccessful in gaining state power. In 2013-14, however, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) gained control over substantial territory in both countries. It declared a caliphate and instituted a reign of terror over this territory. A coalition of forces made up of Iraq, the United States, rebel Syrian and Kurdish armies and Turkey defeated ISIS and reduced its sway in the two countries.

ISIS, along with al Qaeda, recruited a substantial number of armed fighters now fighting in conflict-ridden areas in Asia and northern parts of Africa, such as Boko Haram in Nigeria (see Country Study in this section). Such violent groups create instability and undermine democratic states. The rise of extremist sects does not reflect majority views in most Muslim-dominant countries and goes against most historical tradition within Islamic countries.

At the same time, enduring hostility to the state of Israel, including initially a worldwide boycott, fueled high levels of anti-Semitism in Arab dictatorships and other Muslim-dominant countries where Jews lived for centuries. As a result, Jews emigrated on a large scale from many countries to Israel (see Country Study). Jewish communities in Arab countries today are quite small. There also have been many terrorist attacks on Jews over decades both inside and outside Israel. The mass killings of 1,200 civilians in Israel by the Iranian-backed group Hamas on October 7, 2023 was the largest loss of Jewish life in any terrorist or military attack since the Holocaust.

Religious Freedom in Democracies

As noted above, countries adopting constitutional democracy as a governing structure throughout the 19th and 20th centuries over time adopted greater levels of religious freedom. Even in countries that adopted state religions or had dominant religious hierarchies influencing public policy passed laws establishing freedom of worship. This was the case also in decolonizing countries, like India, and other new democracies.

[C]ountries adopting constitutional democracy as a governing structure throughout the 19th and 20th centuries over time adopted greater levels of religious freedom.

It was on this basis that freedom of religion and conscience was adopted in the UDHR and became a broad international standard that even dictatorships had to answer to at some level. In most democracies, there is an unprecedented level of freedom of religion, with rising tolerance for a wide range of religions as well as non-adherence to religious faiths. Recently, in several democracies such as Ireland and Mexico, the majority of citizens have also voted to thwart the dominance of religious institutions in setting certain unpopular policies, such as prohibiting abortion.

Yet, there remain tensions within democracies in regard to freedom of religion and conscience. In several Muslim-dominant countries, Islam remains the official religion with some level of discrimination against non-Muslim religious groups. In Indonesia, Malaysia, Tunisia and Turkey, which have varied and fluctuating degrees of democratic practice in Freedom House surveys, there is general freedom of religion and conscience (see Country Studies). In all four countries, Islamist-oriented parties compete within democratic political systems without the fanaticism of the groups described above or a theocratic religious doctrine. Even so, the leader of the Islamist party in Turkey has used religion as one means to gain and exert greater authoritarian power, while in Indonesia blasphemy laws are used against government and civil society critics and all Muslims must submit to Sharia courts.

In most democracies, there is an unprecedented level of freedom of religion, with rising tolerance for a wide range of religions as well as non-adherence to religious faiths.

The phenomenon of “backtracking democracies” is frequently associated with the rise of authoritarian parties appealing to religious faith or tradition as a basis for support. In Poland, Hungary, Turkey and India, far right-wing parties and leaders often invoke religious principles against “Western liberalism” as a basis for adopting authoritarian policies. In each of these countries, leaders appeal to religious exclusion and support discrimination based on religious views. In general, such “far right” parties, reject tolerance for sexual and religious minorities or policies like legal adoption of contraception and abortion as freedoms. There is a disturbing affinity between such parties and authoritarian states like the Russian Federation, where the autocrat Vladimir Putin has appealed to religious tradition and introduced repressive religious legislation, including a ban on “homosexual ideology.”

There is also intolerance in some Muslim communities towards liberal principles of freedom of conscience and freedom of speech. The publication of cartoons mocking the Prophet Muhammad in a regional newspaper in Denmark in 2006, for example, resulted in violent demonstrations around the world demanding the censorship of any such images (see History in Freedom of Expression). In many disenfranchised minority Muslim communities in Europe, messages of intolerance are frequently spread by extremist clerics.

The content on this page was last updated on .