Summary

Map of Chile

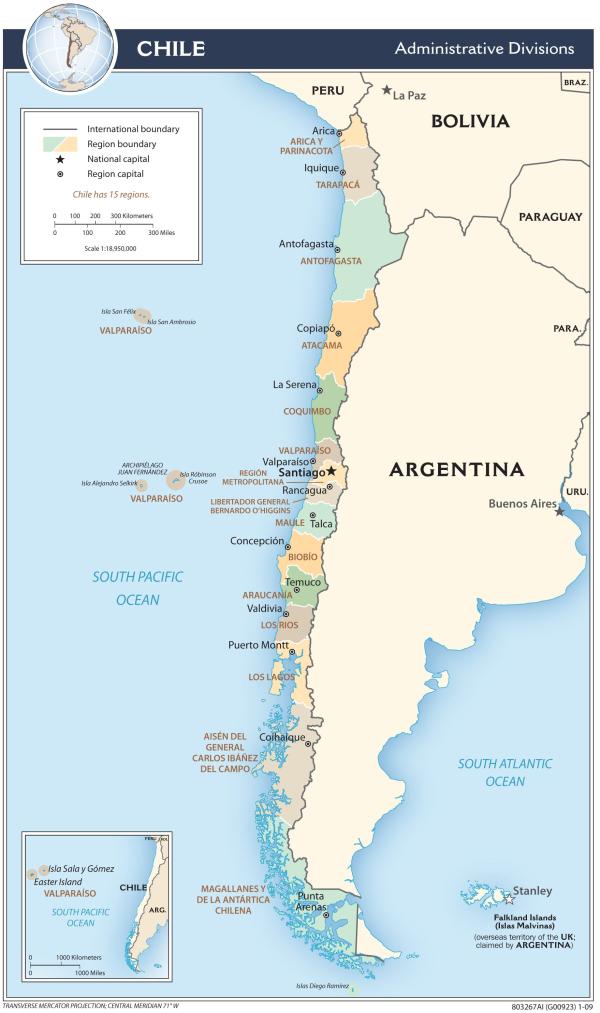

Chile, a country that spans a long length of territory on the Pacific Coast of South America, is a unitary republic with a mixed presidential-parliamentary system.

A colony of the Spanish Empire, Chile gained full independence in 1818, among the first on the continent. It enjoyed a more democratic history than most Latin American countries. A “Golden Era” of democracy starting in 1932 ended in 1973 when General Augusto Pinochet overthrew President Salvador Allende to begin sixteen years of harsh military dictatorship. Democracy was restored after 1988, when Chile’s citizens mobilized to defeat a national referendum for continuing Pinochet’s rule.

Since then, Chile has had eight free and fair national presidential elections, seven national legislative elections and seven nationwide municipal elections. There is a vibrant multiparty system, with four recent transfers of power between parties. Still, there is an ongoing legacy of division resulting from the Pinochet dictatorship that has prevented many democratic reforms.

Chile has a long tradition of freedom of association. Its free trade unions played a key role in resisting the Pinochet dictatorship and restoring the country’s democracy. Yet, constitutional provisions entrenching Pinochet’s neo-liberal economic policies still limit trade union representation.

Chile gained full independence in 1818, among the first on the continent. It enjoyed a more democratic history than most Latin American countries.

Chile is the 37th largest country in the world, with an average width of 100 miles east to west but stretching 2,700 miles south of Peru. There are 19.6 million people (2023 UN estimate). A majority are white and a minority mestizo, or mixed race. Eight percent identify as Amerindian. By religious affiliation, 62 percent are Christian (mostly Catholic) and 37 percent unaffiliated. The International Monetary Fund ranked Chile 4th in Latin America and 45th in the world in nominal gross domestic product in 2023 ($344 billion in total output). Chile ranked 60th in nominal GDP per capita ($17,254 per annum), an improvement from 76th in 2006. Still, Chile ranks second worst in income inequality among the current 34 countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

History

Precolonial Chile and the Spanish Conquest

Before the 16th century, the territory of Chile was populated by three main Amerindian groups: the Inca-dominated north; the Araucanian people of the central region; and the Mapuche, who were dominant in the south. In 1520, Ferdinand Magellan passed through the southern strait of South America (now called the Strait of Magellan) to explore the Pacific Coast.

In 1540, an expedition by Pedro de Valdivia, shown above, established the settlements of Santiago, Concepcion and Valdivia, but his southward conquest for the Spanish Empire was stopped by the Mapuche, who resisted colonization until the late 19th century. Public Domain.

In 1540, an expedition by Pedro de Valdivia established the Spanish settlements of Santiago de Chile, Concepcion and Valdivia. But his southward conquest was stopped in 1553 by the Mapuche, who resisted colonization until the late 19th century. Chile’s territory was placed under the viceroyalty of Peru in Spain’s administration. It became an autonomous colony only in 1778.

Unlike Peru and Bolivia (see Country Study), which were sources of mineral wealth for the Spanish Empire, Chile served as a source of food and animal products. Spanish settlers came in significant numbers starting in the mid–17th century to establish large estates (latifundia) that initially were worked by conquered indigenous peoples. Later, they were worked by mestizo tenant farmers tied to landowners through debt and barter relationships. The practice of slavery was not as widespread as elsewhere on the continent. Six thousand Africans were brought to Chile during the colonial period. In 1823, Chile was second, after Haiti, to abolish slavery in the Western Hemisphere.

Independence, Stable Governance & Borders

In 1810, Chileans established local self-rule after Napoleon Bonaparte's defeat of Spain and his unseating of the Spanish monarchy. Spanish troops regained control in 1814 when Napoleon’s empire collapsed and Ferdinand VII was restored to the throne. Three years later, however, an exile army crossed the Andes from Argentina led by José de San Martín and Bernardo O'Higgins to defeat royalist troops.

José San Martín then went to help liberate Peru. O'Higgins, the illegitimate son of a notable's daughter and an Irish-born Spanish officer, became Chile's first "supreme director" in 1817.

José San Martín then went to help liberate Peru. O'Higgins, the illegitimate son of a notable's daughter and an Irish-born Spanish officer, became Chile's first "supreme director" in 1817. He was elected the country’s first president with the formal declaration of independence in 1818. O’Higgins was later ousted in a coup in 1823 and lived the rest of his life in exile.

After a period of instability, a new constitution adopted in 1833 brought a stretch of stable governance with regular civilian transfers of power but mixed with periods of military rule. The constitution put in place a strong presidency and a weak legislature. The national Congress gained greater authority in 1891 when legislators ousted one president for attempting a dictatorship. Thereafter, a multiparty parliamentary system became more entrenched as the Conservative and Liberal Parties alternated power. Yet, both parties represented property-owning classes. Suffrage was limited by literacy requirements.

The country's current borders were largely established in 1881 when Chile and Argentina agreed to mark their respective territory by the Andean ridgeline and to partition Tierra del Fuego, the large archipelago at South America’s southern tip. During the War of the Pacific (1879–84), Chile also obtained the nitrate-rich Atacama region from Peru and Bolivia.

A "Golden Era" of Democracy

After a brief period of military rule, a civilian democracy was restored in 1932 with the election of Arturo Alessandri. The election marks the beginning of a 40-year period known as Chile's “golden era” of democracy.

[A] civilian democracy was restored in 1932 with the election of Arturo Alessandri. The election marks the beginning of a 40-year period known as Chile's “golden era” of democracy.

The 1925 Constitution, suspended during the period of military control, was restored. A new labor code enacted legalized labor unions and permitted strikes. In this period, Chile's politics were mainly dominated by the middle-class based Radical Party. It ruled in shifting coalitions with left- and right-wing parties. In 1964, however, Christian Democrat Eduardo Frei won the presidency. His party gained a congressional majority in parliamentary elections in 1965.

Although considered a center-right party, Frei implemented a progressive platform called "Revolution in Liberty," which included land reform, investment in education and housing, taking majority stakes in US-owned copper mines and expanding suffrage to 18-year-olds and finally eliminating literacy requirements.

The Golden Era Ends

In the 1970 elections, Socialist Party leader Salvador Allende, the candidate of a left-wing coalition, won a plurality of 36 percent and was awarded the presidency by a majority in the Congress.

In the 1970 elections, Socialist Party leader Salvador Allende, the candidate of a left-wing coalition, won a plurality of 36 percent and was awarded the presidency by a majority in the Congress. It was the first time Chile had elected a socialist leader. Allende set out on an even more radical program than the Christian Democrats by fully nationalizing mines and banks, confiscating large estates, redistributing the land to peasants and raising wages. He also established more friendly relations with Cuba, which was aligned with the Soviet Union at a tense period in the Cold War. (Cuba’s leader, Fidel Castro, made a month-long trip to Chile in 1971, but then strongly criticized Allende for not being “Marxist” enough.)

Many of Allende’s policies were popular but he faced political resistance due to high inflation and opposition from center-right political parties, business interests and some parts of the military. In August 1973, General Augusto Pinochet maneuvered to replace the head of the armed forces, who was loyal to the civilian government. One month later, with support from the Nixon Administration in the United States, Pinochet led a military coup to depose Allende. During an assault on the presidential palace, Allende took his own life rather than surrender to arrest. Eighty people were killed.

In 1970 elections, Socialist Party leader Salvador Allende won a plurality and was awarded the presidency by Chile’s Congress. He was overthrown in a military coup by General Augusto Pinochet in 1973. Above, supporters of Allende mass in his support before the coup. Public Domain.

Pinochet's Dictatorship

Pinochet introduced a harsh military dictatorship. It was marked by mass political detention, limitations on all basic freedoms, suppression of Chile's democratic institutions, thousands of disappearances and extrajudicial killings of opponents.

Pinochet introduced a harsh military dictatorship. It was marked by mass political detention, limitations on all basic freedoms, suppression of Chile's democratic institutions, thousands of disappearances and extrajudicial killings of opponents. (Pinochet’s practices included having opponents thrown from helicopters into the ocean and ordering secret services to carry out assassinations outside the country.) According to two commissions that documented human rights violations after the return of democracy, more than 3,000 people were killed or “disappeared” and 38,254 were imprisoned or tortured during Pinochet’s dictatorship.

The regime's human rights violations isolated Chile from the democratic world, including the United States, which adopted policies in support of human rights after the Nixon Administration and imposed trade sanctions.

The “Campaign for the No”

In October 1988, the "No" vote won, 55 percent to 43 percent. By terms of his own constitution, Pinochet had to step down as president, amend the constitution and hold a presidential election within 17 months of the plebiscite.

A new constitution adopted in 1980 entrenched Pinochet’s military regime and there appeared little hope of challenging it. The constitution, however, required that a referendum be held after eight years on whether the general should rule for another term. Pinochet, confident of controlling the outcome, had included the provision as a nod to democratic formality. But a broad coalition of political parties, trade unions and civic groups turned the referendum into a genuine contest with the “Campaign for the NO!”

With the process under scrutiny by the U.S. and other foreign governments, electoral officials established relatively fair rules for the plebiscite. In October 1988, the "No" vote won, 55 percent to 43 percent. By terms of his own constitution, Pinochet had to step down as president, amend the constitution and hold a presidential election within 17 months of the plebiscite. Under strong international pressure, Pinochet accepted the defeat.

Restoring Democracy Without Justice

There was not a new constitution. . . . To avoid impasse, the parties agreed to maintain some of the military's institutional privileges, including a lifetime Senate seat for Pinochet. But they reinstituted many prior democratic norms and establishing fair procedures for elections.

There was not a new constitution. Instead, fifty-four constitutional reforms negotiated between the democratic parties and the government were approved in a referendum held in July 1989. To avoid impasse, the parties agreed to maintain some of the military's institutional privileges, including a lifetime Senate seat for Pinochet. But they reinstituted many prior democratic norms and established fair procedures for elections.

Patricio Aylwin handily defeated the Pinochet-backed candidate in presidential elections in December. He ran as the candidate of the Coalition of Parties for Democracy, known as the Concertación. It included Aylwin’s Christian Democrats, the Socialist and Radical Parties, among others.

Aylwin's inauguration in March 1990 brought Chile back into the community of democratic nations. But the 1989 constitutional settlement left Pinochet and his cohort immune for past crimes due to a 1978 amnesty decree. In 1998, while traveling to Britain, Pinochet was extradited to Spain on a warrant issued by its Supreme Court on grounds of international jurisdiction to try crimes against humanity. In the end, Pinochet was released before trial for health reasons. Returning to Chile, he faced tax evasion charges but still dodged charges for crimes from his period of rule. He died in December 2006 before proceedings in the tax case were begun.

Patricio Aylwin won the presidency in 1989 leading the Concertatión coalition after the “No” campaign ended Pinochet’s dictatorship. Above, Aylwin at his inauguration wearing the presidential sash. Creative Commons. Photo courtesy of Gobierno de Chile.

The 1978 Amnesty Decree remains in effect but was deemed partly invalid by the Supreme Court. This allowed the government to prosecute some former officials for human rights violations. Of the more than 1,000 cases initiated against individuals for human rights abuses, 260 people had been convicted but only 60 served prison sentences.

Subsequent amendments to the constitution removed some other nondemocratic provisions in the 1980 constitution, including to restore civilian control over the military and to expand powers of the bi-cameral legislature. Presidential terms were shortened from six to four years and a bar was put on serving consecutive terms and two non-consecutive terms total. Still, other provisions remained. The most important were “subsidiary” state principles leaving most functions of government privatized and limiting the role of trade unions. There remained large dissatisfaction at Chile’s charter (see below).

Free and Fair Elections

After winning the presidential and legislative elections in 1989, the Concertación coalition remained united and won subsequent presidential elections in 1993 and 1999. (The presidency then changed to a four-year term.) It also won majorities in legislative elections in 1997 and 2001.

In 2005, the Concertación candidate, Socialist Party leader Michelle Bachelet, won the presidential election, becoming the first woman president (and second socialist) in Chile’s history. She had high popularity but was barred from a consecutive term. In a run-off election in January 2010, Sebastián Piñera of the pro-business Coalition for Change defeated the Concertación candidate, ending a 20-year-period of political dominance. Concertación also lost its majority in both chambers of Congress.

Piñera earned initial popularity as well, but starting in 2011, the government faced ongoing national student protests due to proposed budget cuts in education and imposing tuition increases in higher education (see also Freedom of Association below).

Transfers of Power, Alternating Platforms

Bachelet pledged to address Chile’s social inequities. A tax reform plan increasing corporate taxes and ending corporate tax exemptions quickly passed, but an economic slowdown weakened momentum for other key reforms.

The main left and right political coalitions decided to hold primaries to select presidential candidates for the 2013 elections. In a precedent for Chile (and the Americas) the two main leaders selected were both women. Socialist Party leader Michelle Bachelet, running now for Nueva Majoria (New Majority), won with 62 percent in the run-off vote. Nueva Majoria, an expansion of the Concertación, also won back a majority in the Chamber of Deputies and Senate.

Bachelet pledged to address Chile’s social inequities. A tax reform plan increasing corporate taxes and ending corporate tax exemptions quickly passed, but an economic slowdown weakened momentum for other key reforms. These included a plan for universal free education and a labor reform law to end Pinochet-era restrictions on organizing. Bachelet’s push to adopt a new constitution to replace the 1980 charter also stalled. Bachelet’s popularity declined to 20 percent in the wake of several corruption scandals in her administration, one involving her son and daughter-in-law.

Freedom of Association

Liberal reformer Francisco Bilbao returned from Europe after witnessing the 1848 Revolutions to organize the Sociedad de la Igueldad (Society of Equality), Chile’s first worker association. With 600,000 members, it organized education, training and mutual aid programs. Public Domain.

Freedom of association and Chile’s trade union movement have played an important role in Chile’s modern history. But a political party-affiliated federation structure resulted in disunity and political division within the trade union movement during Chile’s “Golden Era of Democracy.” Under the Pinochet dictatorship, freedom of association was fully curtailed and the regime tried to impose state-controlled unions. Despite repression, free trade unions resisted and maintained some level of independence, but without effective power to bargain nationally. In the late 1980s, a newly united free trade union federation was central to the “Campaign for the NO,” whose victory ended Pinochet’s rule.

Yet, the labor movement did not benefit significantly from democratic governments, which mostly did not break from Pinochet’s constitutionally entrenched free market policies. In recent decades, there have been attempts by students and trade unions to address the country’s high level of income inequality and adopt a new labor law to broaden trade union rights. Below is a description of the role of Chile’s labor movement. Further developments are described in Current Issues.

The Emergence of Chile’s Labor Movement

This early period featured some victories, such as a law for an eight-hour day. Chile was also an original member of the ILO, joining in 1919. It adopted two of the original core conventions banning forced labor and child labor.

Mutual aid societies were Chile’s first worker associations. They were initiated by liberal reformer Francisco Bilbao after he had traveled to Europe and witnessed the 1848 revolutions on the continent. He returned to organize the Sociedad de la Igueldad (Society of Equality).

The Societies involved 600,000 members and promoted mutual aid programs for workers and worker education. Artisan workers then formed a union confederation in 1878. Mining unions organized in the 1880s with the growing industrial exploitation of nitrate and copper. This early period featured some victories, such as a law for an eight-hour day. Chile was also an original member of the ILO, joining in 1919. It adopted two of the original core conventions banning forced labor and child labor.

A Politicized Trade Union Movement

In the early 1900s, Luis Emilio Recabarren, a typesetter by trade, led the organization of two union federations. He adopted a common labor strategy in Latin America of associating trade unions with political parties. In 1912, he also organized the Socialist Workers Party in 1912 and then Communist Party in 1922, in each case allying trade unions he had helped organize.

The right to organize unions was established in the democratic 1925 constitution and workers increased their numbers in party-linked union federations. Over time, these unions succeeded in improving wages and conditions for some of Chile’s workers. In the 1960s, left-wing unions and parties pushed for more radical policies than those initiated by President Eduardo Frei and his Christian Democrats (see above). When Socialist president Salvador Allende set out to nationalize industries and redistribute land and wealth, the labor movement divided in their response according to affiliation with the Communist, Socialist and Christian Democratic parties.

Pinochet's "Plan Laboral" and the Campaign for the "No"

After his coup ousting Salvador Allende in 1973, General Pinochet set out to re-orient Chile’s economy away from state-directed policies towards a radical free market economy.

After his coup ousting Salvador Allende in 1973, General Pinochet set out to re-orient Chile’s economy away from state-directed policies towards a radical free market economy. Advising Pinochet were free market economists from the University of Chicago (dubbed “the Chicago boys”). Adopting their proposals, Pinochet privatized all services (including provision of water); he rid the country of its social welfare system; and he outlawed unions linked to leftist political parties. Any national union activity was made illegal. He formalized these policies in the 1980 Constitution, which made the state “subsidiary” to private interests.

Pinochet’s Plan Laboral (Labor Plan) reintroduced collective bargaining in 1979 but restricted it to the enterprise or individual contract level. It excluded bargaining by trade or on a national level. The regime tried to organize pro-regime unions, but workers undertook to re-organize independent unions at the enterprise level.

[A] consensus emerged within the Chilean labor movement to end ideological division. Labor leaders representing different parties created the Central Unitaria de Trabajadores (CUT)

After an attempt by some anti-Pinochet unions to organize national strikes in 1983 resulted in harsh repression, a consensus emerged within the Chilean labor movement to end ideological division. Labor leaders representing different parties created the Central Unitaria de Trabajadores (CUT). Acting together with professional associations, CUT was a major force pushing the opposition political parties to unite in the Concertación de Partidos por la Democracia (Concert of Parties for Democracy). The CUT and professional associations worked together with the Concertación in the 1988 “Campaign for the No" vote that forced Pinochet from power (see above). This broadly based campaign renewed and reinvigorated Chile's civil society.

The Second “Golden” Age

After 1990, Chile set out to strengthen adherence to international human rights conventions. By 2000, it ratified the ILO’s eight core conventions, including No. 87 on freedom of association and No. 98 on collective bargaining and the right to strike. In April 2011, Convention No. 187 on Occupational Safety and Health was adopted in the wake of a mining disaster.

Yet, adopting ILO conventions did not change the legal situation for Chile’s still-constrained labor movement. While the Concertatión had a broad spectrum of parties, center-right leaders dominated and continued Pinochet-era free market policies. CUT had a limited role in policy making.

[Chilean labor law] continued to be based on the original 1979 Plan Laboral and 1980 Constitution. . . . It also included a controversial "needs of the company" clause. This allowed dismissal of workers for economic downsizing that employers frequently used to fire union members.

A labor reform bill adopted in 1990 expanded the rights of workers to bargain collectively, but still at the enterprise level. A second reform bill to broaden union organization was introduced in 1995 but stalled for six years in the conservative Senate. After adoption in 2001, union density (the proportion of the workforce in trade unions) increased from 13.1 percent to 15.8 percent in 2011 (an increase of more than 600,000 members). It is one of few cases of increased unionization in industrialized countries in the last three decades.

Chilean labor law, however, continued to be based on the original 1979 Plan Laboral and 1980 Constitution, retaining restrictions on both organizing and the right to strike. It also included a controversial "needs of the company" clause. This allowed dismissal of workers for economic downsizing that employers frequently used to fire union members or strike participants.

A Rebellion Against Neo-Liberalism

Chile’s economy had high growth after 1990. In 2010, it became the first Latin American country to join the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Poverty rates halved from that time. Nevertheless, Chile entered the OECD with the highest inequality rate of any of the industrialized countries by far. Among the poorest population sectors were retirees. Chile’s pension system, privatized since 1980, had worked to enrich private investment management firms (APAs) that took 10 percent of a worker’s income. But it repaid retirees just $200 per month on average.

As well, opportunities for upper secondary and higher education were limited by poor investment in education. Parents had to pay increasing levels of private payments from elementary level on to get in to “better” schools. A country that boasts some of the best education institutions in Latin America remained highly limited in its opportunities. Only 45 percent of student-age Chileans graduated from secondary school in 2006 and many graduates could not attend the mostly private university system.

The situation gave rise to national protests by students in 2006 to demand greater investment and key reforms in the education system. . . . In 2011, students protested again when the conservative government of Sebastián Piñera enacted tuition increases for public universities.

The situation gave rise to national protests by students in 2006 to demand greater investment and key reforms in the education system. Michelle Bachelet, in her first term as president, responded by modestly increasing education spending and agreeing to student participation in education policy. In 2011, students protested again when the conservative government of Sebastián Piñera enacted tuition increases for public universities. The increases priced many students out of higher education. Over two years, the Confederation of Chilean Student Federations (ConFech) organized mass demonstrations, sometimes in the face of police force.

In the largest protest, in April 2012, 100,000 young people marched under the slogan “equal education for all.” The government finally responded to the demands by increasing education funding by $5 billion, but President Piñera rejected demands to enact free public education at the secondary and higher education levels.

Major student and labor demonstrations were also organized in 2014 and 2015 to support proposals made by President Michelle Bachelet, then in her second term, for tax reform, greater investment in education and a new labor law removing restrictions on unions. But even with such strong public support, the measures failed to pass in the face of right-wing political opposition.

Current Issues

Since 2016, Chile has seen a continuation of the political contest between the political right and political left that is a reflection of the country’s past. Despite some violence and police use of force, this political battle has been conducted within democratic constraints due to the firm consensus built in 1990 following the Pinochet dictatorship. Nevertheless, as described below, efforts to establish a new constitution were rejected by voters, leaving proposed reforms in a stalemate.

Since 2016, Chile has seen a continuation of the political contest between the political right and political left that is a reflection of the country’s past.

In 2017, Chilean voters returned wealthy businessman Sebastián Piñera to the presidency. Leading a new right-wing coalition called Chile Vamos (Chile, Let’s Go), he won by 55 percent to 45 percent over the candidate of the center-left Nueva Majoria (New Majority).

An electoral reform bill had gotten rid of the Pinochet-era binomial system that favored a dominant two-party system and introduced multicandidate constituencies for an expanded legislature. Chile Vamos won a strong plurality with 38 percent of the seats in both the Chamber of Deputies (now with 155 seats total) and the Senate (now with 50 seats). Nueva Majoria got 24 percent of seats in the Chamber of Deputies and 22 percent in the Senate. Frente Amplio (Broad Front), a new coalition of six left-wing parties emerging student- and labor-led protest movements, gained 16 and 11 percent of seats in the two chambers.

President Piñera, harking back to previous pro-free market policies, restored tax concessions for business and then in 2019 introduced an increase in the fare for public transportation. Although the increase was modest, this last sparked a major rebellion of students, workers and retirees. Called estallido (“the explosion”), the protests centered on the great rise in inequality in the country since 1980. An estimated 3 million people total were involved.

Estallido had a wide impact. Although the police used force against the protests, they continued over months and Piñera in the end was forced to rescind the metro fare increase. He also conceded to demands for investments in education and to a proposed referendum for overhauling the 1980 Constitution.

Quickly, in 2020, Chilean voters approved a referendum calling for a new constitution by 78 to 22 percent. In the general elections in 2021, Gabriel Boric, a leader of the student protest movement and now head of the left-wing Broad Front coalition, was elected president. The Chamber of Deputies and Senate, however, remained fragmented under the new multicandidate system. Twenty-two parties were now represented, plus a large number of independents, making achieving a majority on any legislation difficult.

The referendum led to elections for a Constitutional Convention. Left-wing parties won a decisive majority. The proposed constitution removed the “subsidiary” principle of the 1980 Constitution that privatized all services (see above) and established constitutional rights to education, jobs and health care. It also protected a wide range of rights for women and the LGBTQ community and proposed to make Chile a plurinational state to include the Mapuche Amerindians as a distinct nation.

This left-oriented constitution, however, was rejected in September 2022 (68 percent to 32 percent) due to fears that it did not protect property rights and to objections that it expanded state protections to constituencies beyond Chile’s traditional norms. This decisive defeat led to another election to a Constitutional Delegate Assembly, this time dominated by right-wing parties. The Assembly proposed a constitution that re-affirmed much of the earlier 1980 Constitution. It, too, was soundly rejected by voters in December 2023.

This second rejection led President Boric to announce that the process for constitutional renewal had ended. Reforms would be sought within the existing amended constitution. Boric’s reform efforts, however, have stalled, with a tax reform plan and a pension reform plan rejected by the Congress.

• • •

In 2019, a public transportation fare increase sparked a protest movement of students, workers and retirees lasting months. Called “the explosion,” the protests centered on the rise in inequality and limits in public services in the country. Despite concessions by the government, reforms remain stalled. Creative Commons. Photo by Natalia Reyes Escobar.

Chile remains a politically divided country that is still broadly affected by the political dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet now more than 50 years since the coup against president Salvador Allende (see links in Resources on the coup’s anniversary). The consequences remain with Chilean society. As part of marking the anniversary, for example, President Boric announced a new commission to finally determine the fate of all of the 3,000 “disappeared.”

Still, a political consensus has held around the restoration of democracy. Chile holds free and fair elections and, with limited exceptions, respects freedom of expression, due process, freedom of assembly, freedom of religion, freedom of movement and other rights. Freedom of association is broadly respected and played an important role in recent events. Even so, trade union rights remain restricted. There also remain restrictions on privacy rights (for example on abortion and gay marriage).

The content on this page was last updated on .